by Martin Kufus

If Hezbollah’s rocket barrages into northern Israel seem to be a recent phenomenon, they aren’t. As former Soldier of Fortune magazine editor Martin Kufus writes, deadly cross-border attacks from southern Lebanon began decades ago. The following is an excerpt from chapter “L is for Lebanon” of his nonfiction book.

Despite having spent a month in the Sahara during the “Bright Star ’83” joint US-Egyptian military exercise, I’d never fully grasped the Middle East’s complexities until six years later, as a graduate-student intern at the Associated Press (AP) bureau in Jerusalem. The journalism school at Ohio University–Athens sent me to Israel in fall 1989 in the only foreign-correspondence internship program of its kind in America. Having left the Army a year earlier, I still tended to view current events through a military lens.

In Israel, that wasn’t such a bad thing for an inexperienced foreign journalist.

READ MORE from Martin Kufus: ‘G is For Gonzo’: A Slice From an Editor’s Life at Soldier of Fortune

One of my Middle East “lessons” began routinely enough one morning in the AP bureau, which occupied an upstairs suite in an office building off busy Jaffa Street in downtown Jerusalem. Bureau Chief Nicolas B. Tatro had received a media advisory from the government press office in the Beit Agron office complex a few blocks away: The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) would host credentialed foreign news-media representatives on a tour of the Israeli-controlled security zone in southern Lebanon two days hence. Tatro, an old AP–Beirut hand, asked if I wanted to go to Lebanon.

“Yes, of course,” I replied.

Tatro chuckled, then instructed me to contact a rental-car agency a few blocks away and reserve a small car on AP’s tab and to book a room at a certain hotel in Metula, my destination. Thus assigned, I made phone calls. I found a map of Israel, spread it out on the desk in the newsroom, and planned my route. From downtown Jerusalem to Metula, the farthest-north town in Israel, I figured, would be a drive of 226 kilometers (141 miles).

Two AP staff writers looked over my shoulder, concurred with my route selection, and cautioned me to be careful. Drivers’ habits, widths and conditions of the roads, and the minimal occurrence of multilingual road signs—it was not like driving back in the States, they warned. Also, unspoken but understood, was the specter of random violence in the intifada, the Palestinian uprising now in its second year. On the other hand, it also was understood at AP that foreign journalists were not targeted for the intifada’s sporadic violence.

The morning before the IDF’s media tour, I claimed the rental car, a Volvo compact, and tossed my Lowe backpack/suitcase onto the back seat. My first task was to get out of Jerusalem, drive east on Highway 1, and connect with northbound Highway 90. On these busy, narrow streets a Jerusalem map and Silva compass could only do so much in the absence of local knowledge. Soon, just past the ancient walls of the Old City, I was turned around in East Jerusalem. Stopped in heavy traffic, I consulted the map and looked around.

A teenager dressed in a soccer shirt, blue jeans, and jogging shoes came to my half-open passenger window, leaned down, and enquired in lightly accented English, “Are you lost?”

“Yes,” I said.

“American?” he said, grinning.

“Yes, I am a journalist,” I replied. “I am trying to find Highway 1 to Jericho.”

For X number of shekels, the young Palestinian businessman said, he would guide me through East Jerusalem. He got in. After a few minutes of his expert navigation, he pointed to a road sign that stated, “To Highway 1” in Hebrew, Arabic, and English.

“Turn that way,” he said, pointing. I paid him and we parted company.

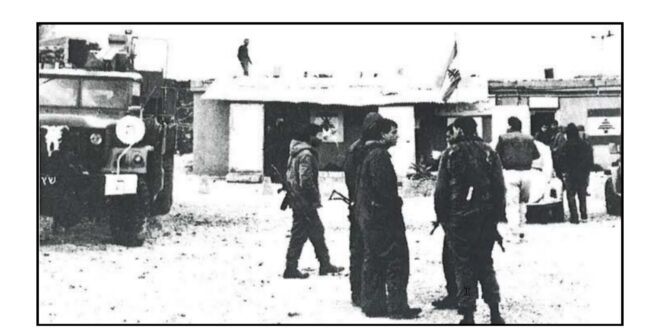

SLA troops on a US-made M113 APC rumble by on patrol in 1989 in the Israel-controlled Security Zone.

Jerusalem in my rearview mirror, I was traveling in what was known as the Occupied West Bank. It would be another 25 kilometers on Highway 1 eastbound until the intersection with Highway 90. There, I turned north and soon skirted Jericho. After 112 kilometers altogether of heads-up driving on Highway 90, I would reach the southern tip of the Sea of Galilee (Kinneret in Hebrew), through which flowed the Jordan River.

When I eventually entered Metula, a picturesque hilltop community of about 700 residents, I noticed the public bomb shelters—all maintained and ready for use on a moment’s notice during a rocket attack from across the border. I found the European-looking Arazim Hotel and checked in.

READ MORE from Martin Kufus: We Trained Under Special Forces Legend Nick Rowe

That night, a faint glow got my attention. I looked out a window. A parachute flare, maybe 2–3 kilometers away, illuminated an area across the fortified border. Then, another flare zoomed skyward to erupt into light and descend slowly under a small parachute. I could make out headlights from two or three vehicles moving in concert. A patrol from the South Lebanon Army (SLA) or one from the IDF’s Golani infantry brigade was looking for would-be infiltrators, perhaps. There was no gunfire and no more flares, so I returned to bed.

The next morning, I drove to the IDF’s garrison in Metula. Not far from the military installation’s main buildings was one of four IDF-controlled border crossings. Collectively, these Israel–Lebanon passages were known as the “Good Fence.” Every day, members of a select group of some 2,000 Lebanese men and women entered these crossings. After showing identification and possibly submitting to personal security inspections, they walked into Israel and climbed aboard chartered buses taking them to work. Each of these migrant workers owed his or her employment—reportedly starting at US $17 a day; American currency was the standard in southern Lebanon—at an Israeli factory, machine shop, farm, hotel, restaurant, or private home to a male relative wearing the SLA uniform.

The Good Fence crossings quietly opened in 1976. In 1985, however, Israel turned an irregularly shaped strip of southern Lebanon—120 kilometers long and 4 to 20 kilometers deep—into a military and economic buffer, known as the Security Zone, against attacks by Hezbollah and other anti-Israel groups. This occurred as the IDF withdrew most of its forces from Lebanon, which it invaded in force in 1982 during Operation Peace for Galilee. The IDF’s goal had been the destruction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and its armed forces, which the IDF chased into Beirut. The extended siege there and heavy Israeli casualties roiled public opinion back home and national politics in Tel Aviv.

At Metula’s “Good Fence” crossing, civilians board a bus for jobs in northern Israel.

By 1989, the Israeli Ministry of Defense had reportedly spent tens of millions of dollars to turn a previously rag-tag militia of mostly Lebanese Christians into a small, structured force in the south. Also, millions of dollars went into public infrastructure—electricity, water, roads, schools, and a hospital—for a security-zone population of 200,000, some of whom had fled the seemingly endless factional war in Beirut. The Security Zone’s population was reported at 60 percent Shi’ite Muslim, 30 percent Christian, and the remainder Sunni Muslim and Druze; the SLA’s composition, however, mostly was 30 percent Shi’ite, 50 percent Christian, and 10 percent Sunni. The pay for an SLA enlisted man in 1989 was $130 a month; officers received $230–$300 a month. Moreover, Israel enticed SLA soldiers to reenlist with annual bonuses of up to $300.

“Today we have no trouble getting volunteers for the SLA,” Israeli Lt. Col. Sharga Kurz told our small group of correspondents, which included a reporter for the Washington Post and crew from CNN, during a no-photos-allowed briefing at the garrison. Kurz knew the Security Zone well as an IDF liaison officer in the Marjayoun, Lebanon, headquarters of the SLA’s commander, Maj. Gen. Antoine Lahad.

On the wall, Kurz’s briefing map showed two dozen SLA outposts positioned along the zone’s northern border, six SLA outposts in the interior, and Lahad’s headquarters. It also showed the IDF’s disposition as two posts inside the zone and 40 positions inside the Israeli border from which artillery and helicopter support could be summoned.

Kurz read off statistics: From the start of 1989 through September 30, there had been 118 incidents of gunfire from guerrillas carrying small arms, RPG-7s, and other light anti-armor weapons; 49 incidents of mortar and rocket fire originating mostly outside the zone; and 80 incidents in which land mines or roadside bombs were planted in the zone. A car bomb was detonated four months earlier, he added, less than a kilometer from Metula’s border crossing—not far from where we now sat—injuring one SLA and five IDF soldiers. In the last two years, about 50 teams of guerrillas had been caught infiltrating the Security Zone.

“In the last four years, SLA soldiers have killed hundreds of terrorists, mostly from Hezbollah and the Syria-backed Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine,” Kurz said. He would not give an exact figure of enemy dead when asked by one of the reporters.

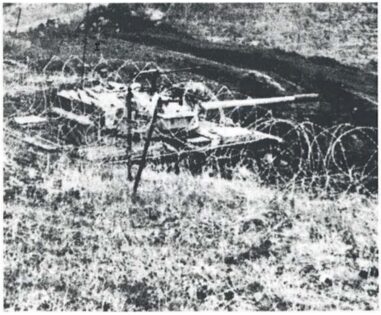

The IDF officer said guerrillas had inflicted casualties, too. In the SLA, 200 soldiers were killed and 600 wounded in four years. In 1986 and 1987, Kurz said, there were frequent attacks on SLA border outposts, which at the time were poorly constructed and inadequately armed. The most embarrassing SLA defeat occurred in 1987 when Hezbollah launched a surprise infantry assault on one position, chased off the SLA defenders, and drove away in an Israeli-supplied armored personnel carrier (APC) with abandoned weapons and ammunition. Since then, the IDF reinforced the outposts with concrete bunkers and firing positions; each post also was assigned a T-55 tank.

A Soviet-made T-55 tank at the SLA’s northernmost outpost in the Security Zone.

The Metula briefing for the foreign press ended after an hour. Kurz and another IDF officer, Maj. Moshe Fogel, an army public-affairs spokesman, ushered us from the building to a VW bus with IDF markings. Each soldier took his basic kit, helmet, and Uzi submachine gun—with a 9-mm ammunition magazine already inserted. Once everybody was in the small bus, we hit the road. Kurz drove at a moderate speed on a two-lane road through rough hills.

Our first stop was the SLA outpost Position Zamaraya, the SLA’s northernmost outpost, located on a hilltop 2 kilometers north of the Druze town of Hasbaya. The outpost’s largest weapon was the 100-mm main gun on an old Soviet-made T-55 tank provided by the Israeli army, which had captured it and others like it from Syria in a past war. In bunkers and concrete-reinforced firing positions surrounded by concertina wire, SLA soldiers watched through binoculars for armed infiltrators skirting checkpoints and sneaking into the zone. The infiltrators would be Shi’ite or Palestinian guerrillas armed with pistols, Kalashnikov rifles, grenade and rocket launchers, land mines, and explosives. Their targets sometimes lay to the south in Israel, but often they were in the zone itself.

“Two months ago, infiltrators came,” said Position Zamaraya’s 38-year-old commander, Lt. Rabia. He said he and his men were alerted by a radio report. “We were on a patrol on Hasbaya Road. We first checked to see if they had left behind any bombs or mines.” Rabia and his infantrymen, in second-hand vehicles, searched the rough countryside for three men who were armed with AK rifles and an RPG-7. “We tracked them, but one got away. Then, after 6 kilometers, we caught up with the other two and we finished them off.”

During our 20-minute stop at Position Zamaraya, I saw light and heavy machine guns and RPG-7s, as well as the standard SLA small arms of AK rifles for enlisted men and American-made M16s for officers. Beefing up the defenses and firepower of the border outposts had the desired effect. “They are afraid to attack the positions, for now,” Kurz said. Overall, he added, the number of “security events” in the zone dropped from two a day in 1988 to one a day in 1989.

The guerrillas changed their tactics; they sought fewer direct confrontations—they would be outnumbered and outgunned—and relied more on the mining and booby-trapping of roads. Backed by armored vehicles, IDF and SLA foot soldiers patrolled roads daily looking for buried mines or command-detonated charges in ditches and bushes.

Ongoing Israeli-funded road-paving made it increasingly difficult for guerrillas to bury mines on heavily traveled roads. So, they might instead lash an artillery or mortar round to a charge fitted with a detonator, run a lengthy electrical wire from the roadside to a concealed position, hook it to a motorcycle battery, and wait for a passing target. But because this was danger-close and within range of the machine guns on the IDF and SLA vehicles, off-the-shelf radio transmitters and receivers were sometimes modified to detonate the bombs at a line-of-sight range of 2–3 kilometers. The IDF responded with limited electronic warfare against this escalation by using vehicles with radio transmitters and antennae to try to prematurely detonate these hidden bombs ahead of their soldiers’ patrols.

During our IDF-conducted road trip, I saw well-maintained Mercedes, BMWs, and Volvos roll by, followed by beat-up economy cars and occasionally a sturdy old truck bearing crates of farm produce. More than half the zone’s approximately 12,000 civilian cars and trucks had been registered and tagged and their drivers licensed in a program ordered by the Israeli liaison mission. The new regulations aimed at helping security forces identify vehicles and drivers coming from outside the zone—perhaps with a car bomb. Moreover, civilian vehicles had to carry at least two people, as suicide car-bombers typically travelled alone.

Even IDF soldiers commonly shuttled around the zone in civilian autos as much as possible. When conditions didn’t require them to move out in APCs (the American-made M113) or military trucks, fire teams of three or four Golani infantrymen piled into used four-door Mercedes, signed out from a small fleet. A low profile was desired. “The goal is to have as few Israeli soldiers here as possible,” said Fogel, the army public-affairs officer. “The glue which keeps the SLA together is self-interest.”

During our trip, the two IDF officers monitored radio traffic in Hebrew on a handheld unit and occasionally transmitted something. At one point, without explanation, Kurz steered the VW bus off the two-lane road. He shut off the engine. The two soldiers nonchalantly grabbed their helmets and Uzis, got out, and walked away from the vehicle. They strolled up the road a short distance, on the other side, stopped, and stood—as if watching for something coming the other way. The Washington Post and CNN representatives and I sat in the vehicle. After two minutes I got antsy. I didn’t like the idea of maybe being somebody’s stationary target of opportunity.

“I’m gonna stretch my legs,” I remarked to my press companions as I exited with my notebook and camera. The IDF officers noticed me but said nothing. I pulled out my notebook and began jotting. Midway through a sentence, I heard an explosion in the distance—mortar round, landmine? I glanced at Kurz and Fogel. They didn’t react.

Our next stop was Marjayoun. On the way, we encountered a military checkpoint—but not IDF or SLA. Kurz pulled over to let us have a look. “Those are UN soldiers from Norway,” Fogel explained simply.

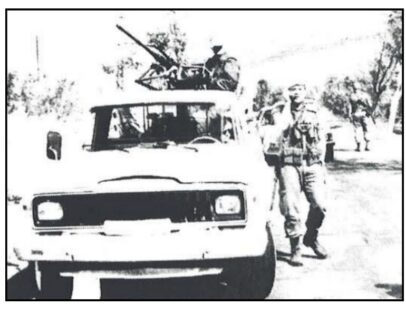

United Nations peacekeepers from Norway conduct a traffic check in the Security Zone.

By 1989, the United National Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL) reportedly comprised 5,800 peacekeeping troops from Nepal, Fiji, Ghana, France, Italy, Sweden, Finland, and Norway, deployed in two sectors, east and west. The Norwegian troops, deployed to the east of the Marjayoun area, were fully within the Israel-declared Security Zone. The other UN troops were widely deployed in the western sector whose northern boundary was the Litani River; this sector was mostly outside and to the north of the zone. UNIFIL’s thankless task was to intercept and halt guerrillas—preferably, without gunfire—before they could make contact with civilians or SLA or IDF soldiers.

According to rules of engagement, UN troops had no arrest authority and could shoot only in self-defense, and then only after shouting warnings and firing shots into the air. There reportedly was bad blood from disputes over jurisdiction—notably, between Golani infantrymen and Norwegian troops—although nothing fatal yet.

The Israeli soldiers believed their mission was to kill or capture guerrillas before they could bury landmines, set booby traps, or fire rockets into Israel, and the peacekeepers got in their way. Recently, there had been a confrontation between an SLA unit and a Norwegian patrol. Without requesting permission, the SLA soldiers entered a village under UNIFIL jurisdiction to capture a Lebanese man. The Norwegians intervened, and an SLA soldier fired an RPG-7 round over their heads. The Norwegians did not return fire; the SLA soldiers hastily departed with their prisoner.

The random checkpoint we stopped at comprised a white pickup truck marked as UN with a driver and, in back, a gunner behind a swivel-mounted .50-caliber Browning machine gun, plus a handful of dismounted Norwegians. The patrol’s officer, sporting a light-blue beret, stood at the driver’s door, talking on a handset. After a few minutes, one of the IDF officers signaled for us to load up.

Read more from Martin Kufus in his book, Plow the Dirt but Watch the Sky

In Marjayoun we toured the zone’s hospital. It was not large but modern, clean, and functional, and featured a small emergency room. One of the reporters asked our IDF tour guides if we could interview General Lahad, the SLA commander. The general was not available, we were told, but his spokesman was. Francis Rizk, a former high-school teacher who worked as the general’s spokesman, was a life-long resident of the Marjayoun area. A sincere man, Rizk was also a writer for an Israeli-funded Christian radio station that broadcast from Marjayoun. He told us the zone’s economy—in terms of wages, goods, and services—was currently estimated at $2 million a month.

“We have a very normal life inside the zone. The incidents occur near or on the border,” said Rizk, who added he had been one of the first migrant workers to enter Metula’s Good Fence in 1976. The zone had its problems, but life there still was more stable than in the Beirut area—the usual standard for comparison. “Our financial situation still is the best in all of Lebanon,” he added.

Afterward, as our VW bus headed back to the IDF garrison in Metula, I wondered: What would happen to people like Rizk if, or when, Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon?

Editor’s note: Ending its 18-year presence in southern Lebanon, the IDF withdrew from the Security Zone in May 2000—soon followed by the SLA’s collapse and Hezbollah’s resurgence.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers