by Royce de Melo

Some meters ahead of me on the left side of the street, two soldiers armed with M16 A1/A2 rifles approach a young man. He definitely caught their attention. As the soldiers in El Salvador calmly walk up to him, the man stops and puts down the gym bag in his right hand. The soldiers talk to him in a relaxed way. He lifts his white short-sleeved polo shirt to reveal his chest and belly, then turns around. They help lift his shirt and look at his back. No tattoos. No tattoos on his arms either. He’s free to go.

In El Salvador, anyone with a gang tattoo can get slapped with up to a 20-year prison sentence. This is part of the “State of Exception,” launched in 2022 after MS-13 massacred 187 people in the single weekend of 25-27 March. In response, President Nayib Bukele declared a state of emergency. In doing so, the small Central American country launched a nationwide war on gangs.

While this clamp-down on gangs was unfolding, in June 2022, I went to El Salvador on a security management contract. Here’s some of what I learned.

The two main rival gangs in the country are MS-13 and Barrio 18, and their respective symbols are easily recognizable.

Obviously, having a gang tattoo is a way of advertising; it’s not only a way for gang members to show affiliation, but it also projects power. It’s meant to intimidate, to make people fearful. Gang tattoos led criminals to believe they had carte blanche to do whatever they wanted, no matter how evil the act. For a long time, they did have virtual free rein. But tattoos can also provide a story and show position or rank, including how many people someone has murdered. We’ve seen members with MS-13 tattooed over their entire faces, both males and females. Such in-your-face tattoos– or should I say ‘on your face tattoos’– made for easy work for Salvadoran security forces in identifying and arresting gang members.

The MS-13 gang went on its murderous weekend spree in retribution for what they believed was a betrayal of a secret agreement they had with Bukele. Other sources claimed that the uptick in violence was retaliation for the government taking control of certain bus routes in the capital, San Salvador, from where the gangs were extorting money. In response to the violence, Bukele went on the offensive and launched an unforgiving war on the gangs.

The result of Bukele’s State of Exception was the virtual destruction of both MS-13 and Barrio 18 in the country, the liberation of areas that for years had been under gang rule, and the locking up of 70,000 gangsters and criminals. It was incredibly successful. El Salvador went from being the most dangerous country in the Western Hemisphere to one of the safest in a remarkably short time.

Under the “Regime of Emergency”, new laws were implemented that might seem draconian to some. Gangs were designated as terrorist organizations, gang symbols were banned, arrests could be arbitrary. By declaring the gangs as terrorists, security forces had more of a free hand to arrest or, if necessary, kill gang members. The declaration put both Salvadoran law enforcement and the armed forces on a war footing.

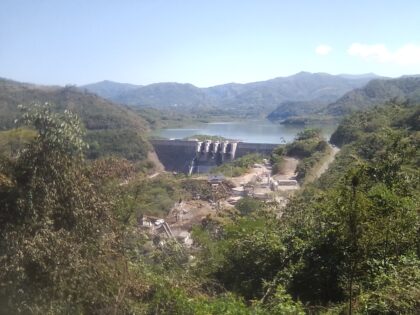

My own contract there was at the El Chaparral Dam construction project. The dam is situated right on the Honduran border along the Torola River. The compound we were based at was secure and very well guarded by the National Civil Police (PNC) and military personnel. The military detachment was from the Salvadoran Navy Infantry Marines.

The Navy infantry Marines carried M16 variations, including the M16A1/A2S, some of which looked like they dated back to the El Salvadoran Civil War (1979 – 1992). There were M16A4s and many carried M4s, of course. I don’t remember ever seeing Canadian C7s with the Navy personnel, but apparently, they are there.

On one particular occasion, I did a favour for a patrol of Navy Infantry Marines by driving five of them in the back of my pickup truck to the other side of the dam. The poor lads had to hump it up and down into the valley, across the dam site, and up again in the mountains. Iit was quite the hike and distance from where I picked them up (before anyone says anything, I don’t think I had them cheat on their patrol route, because I got them to where they needed to be to go on patrol.)

The dam

My tasks included conducting recces in the surrounding areas to assess the situation for reports. If there was a security force’s roadblock, that was worth noting because something was likely afoot. If soldiers were seen on the roads outside of a town or city, it was worth noting. Naturally, I would look at their kit and check to see if it’s new, old or good.

While in the country, the Army’s M16 A1/A2 rifle was being replaced by the IWI (Israel Weapon Industries) ARAD rifles, which were carried by both the army and the PNC. Bukele and his Minister of Defence were seen in the media making a show of it, proudly issuing new IWI ARAD rifles and other equipment to troops, including helmets and body armour.

Bukele was going to one particular source, an Israeli arms dealer, a friend of his, who was virtually a one-stop shop. There didn’t appear to be any public tendering to fill the military and law enforcement requirements. This led to some government opposition to complain about the lack of public tendering, which is required by government policies. That didn’t stop Bukele and his Minister of Defence from direct sourcing.

READ MORE from Royce de Melo: Shooting Canada’s Version of the SVD Dragunov, the Type 81 Sporting Rifle – With Russian Scope

Just before Christmas 2022, the PNC officer I worked with, nicknamed ‘Gavilán’ (‘The Hawk’), the second in command for security at the dam project, told me how bad it was under the gangs, as he had not visited family in Soyapango in six years. He claimed that if he had gone into the area, they would have killed him. That Christmas of 2022, he finally got to visit his family.

I discovered that individuals entering gang-controlled areas had to be cautious about what they wore. Having a black shirt or wearing a certain brand of shoes was enough to have a gangster murder you. Why? Because they can, and only those gang members are allowed to wear black shirts or that brand of shoes.

MS-13 is perceived to be Satanists. There are stories of baby sacrifices and human sacrifices.

Many prisoners now are being held in a mega prison called the Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT). It was being built while I was working in the country. The CECOT can hold as many as 40,000 inmates, which technically violates the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the Mandela Rules. But I don’t care. And most Salvadorans don’t care.

The extortion throughout the country by both MS-13 and Barrio 18 was off the charts, and life was cheap. While the gangs ruled large areas of the country, there was constant fear, intimidation, horrific tortures, and murders that were more than the Salvadorans could bear.

The tattoo identification for arrests was a great idea. However, it didn’t always work out well.

There was one case of a Salvadoran young man who was heavily tattooed and arrested by mistake, accused of being a gang member. On one shoulder, he had an AK-47 rifle tattooed; this tattoo is what got him hauled off to prison. He was saving money to have more added to that tattoo, which was unfinished. He was looking to have a red circle around the AK-47 with an angled line going over and across the AK-47 tattoo, like a ‘no smoking’ sign, but in this case, it would symbolically mean ‘no violence. If it weren’t for friends and neighbours who knew him and vouched for him, who told the police he was not a gang member, that he only liked having lots of tattoos, he might have spent a long time in the clink with real gangsters with pro-violence tattoos. He was released.

With the sweeping powers of arrest, many innocent people were incarcerated. These were casualties of war, Bukele said. Some who were not freed in time died in prison because they were murdered, and others died for lack of medical treatment, some with preexisting conditions.

The abuse of power by security forces was inevitable. There would be cases of deadly retribution against gang members, but it would be hard to prove, especially in this war and the state of emergency. And let’s be honest, there wasn’t going to be a lot of empathy from the Salvadorans if security forces took out an MS13 or Barrio 18 gangster in suspicious circumstances.

I was shown a photo of an MS-13 gang member dressed all in black, sitting cross-legged on the ground in some dry tall grass. It appeared that his hands were cuffed behind his back. I believe the photo was posted online. He’d been captured after a gun battle. In the next photo, he was lying on his back in what appeared to be the same spot he was sitting in the previous photo, but dead, with a pool of blood soaking into the grass around him. He’d been shot.

“He tried to get away,” I was told.

Squeeze a water balloon, and it bulges in unexpected places. Despite the success of this war on gangs, it had negative ramifications for El Salvador’s neighbours.

Speaking with officers in PNC stations in various locations in the area and along the border, it became evident that many gangsters didn’t stick around but scarpered to Honduras and Guatemala, thereby becoming those countries’ problem.

A senior PNC officer in one small town in our zone told me about a mission they conducted near the Honduran border portion of the Rio Torola, targeting a Barrio 18 hideout. The PNC were armed with pistols, he said, while they knew the gangsters were armed with M16s and G3s– the G3s are likely leftovers from the Civil War. However, when they approached the holdout, the gangsters fled toward the shallow river, weapons in hand, and crossed into Honduras, and waved at the officers. There was nothing the PNC could do but notify the Honduran security forces. When the Honduran forces arrived, the gangsters had fled, weapons and all.

In late 2022, Honduras, now dealing with a bigger crime problem, in part because of El Salvadoran gangsters in the country, tried out a lighter, less harsh form of a state of exception. It’s been mildly successful.

All of the regional PNC chiefs and officers I spoke with saw the rapid and tangible changes in crime and violence. By the time I finished in El Salvador, the PNC officers I knew in the region were as happy as could be with the relative peace.

In March 2023, I went on my final embed with the PNC. On this occasion, it was with Inspector Monge, who was headquartered at the station in San Luis de la Reina. Monge was the police chief of the sector. He invited me to accompany him on an inspection route to see what goes on.

Middle-aged, with glasses, Monge had a very calm and friendly demeanour about him.

Before heading out, Monge told me of two recent murders, one in San Antonio and another in San Gerardo nearby. Neither was gang-related. Despite the gangs being crushed, crimes and murders still happen. (Men in the region carry machetes as part of their daily attire, so machetes are a very common weapon used in attacks, drunken fights and murders.)

The vehicle we were to travel in was a rickety old police Nissan pickup. They complained about the lack of proper vehicles and that the Nissan they were using was a 2016 model. I had heard the same complaint from the 2IC at the station in Ciudad Barrios about a lack of proper vehicles.

As a reflection of how secure and comfortable things had become, no other armed PNC officers or soldiers accompanied the Chief, except for his driver. There didn’t seem to be a worry about a run-in with gang members, ambushes, violence, etc. In fact, it all seemed lackadaisical.

We drove west from San Luis de la Reina PNC station to San Gerardo and finally to Santa Lucia Bridge, over the Rio Lemba.

The drive through the winding roads was quiet. Inspector Monge and I didn’t talk much.

Regarding safety concerns, I was more worried about road accidents, the way people drive, drunk drivers, drunk pedestrians, and poor road conditions.

While grabbing a snack from a shop under the Santa Lucia Bridge, I noticed a twenty-something Salvadoran wearing a black short-sleeved shirt and arms covered in tattoos. None of the tattoos looked gang-related; he had generic flames up his forearms, and more. He was with a friend. He was very relaxed and spoke with everyone. The people there, including Inspector Monge, are familiar with him. Black shirt… Tattooed arms… And not a gangster… No fears of being shot for wearing a black shirt, and he certainly didn’t look worried about being arrested or at least checked for gang tattoos by security forces.

It had come to this. How liberating.

Royce de Melo is a Canadian analyst and security and defense consultant mainly covering the Middle East and Africa.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers