Chapter 28

Retaking the Koidu Diamond Fields By Eeben Barlow

Anyone planning to fight a successful armed anti-government or terrorist campaign ought to know that one of the primary objectives (apart from causing mass enemy casualties and loss of materiel) is the denial of funds to the rebel or terrorist forces.

Without finances, rebels/terrorists cannot purchase weapons, ammunition, medical supplies, transport, fuel, clothing, or food—nor can they pay their fellow terrorists if payment is required.

Equally important is the protection of the local population and the projection of disciplined force at the correct time and at the critical point based on sound intelligence. This three-pronged attack aimed at eroding a rebel/terror group’s power base is essential for ending a conflict or war.

Sierra Leone was no exception. As the rebels controlled the diamond and rutile mines—and had plenty of unregulated buyers—they had almost unlimited access to funds. It would have been folly to allow them to continue fuelling their campaign of terror through illegal use of these natural resources.

The media, replete with its armchair strategists and tacticians, saw Executive Outcomes’ work as a sinister ploy to take over the rebel cash-flow for ourselves. Unbeknown to these journalists[1]posing as ‘military specialists’, the reality, in conflicts like those in Angola or Sierra Leone, is that numerous factors impact on how governments and anti-government or terrorist forces achieve their desired end results. Unfortunately, the media and its ‘undisclosed sources’ (DFA, MI, and their host of willing ‘advisors’) seemed to condone the approach followed by the RUF.

Iwan van der Merwe and I flew out of South Africa before the operational design for the advance on Koidu[2]had been finalised. Phillip Hoy of Advanced Communications Systems Ltd., had arranged a meeting between Iwan, myself, and a communications specialist from the German Army and one of his colleagues, to discuss radio communications in hostile and problematic areas. The meeting took place in a military club in the heart of London.

The Germans were astonished to hear that we were running our communications links on HF (high frequency) radios. During the meeting, which lasted for several hours, Iwan explained to a German major (I do not recall his name) how we used HF skip, digital encryption, frequency prediction, and burst transmissions. The major furiously made notes of everything that was discussed. He also told us about the technical problems the Germans had experienced in the first Gulf War, and Iwan and I suggested possible solutions.

He eventually asked Iwan how to set up a tactical and operational radio net. Iwan was prepared for that question and gave him copies of typical tactical radio net and strategic rear-link communications feed diagrammes.

“I thank you for helping the Wehrmacht,”[3]the major said with a smile after the meeting.

“No problem at all. I am pleased Iwan’s knowledge was of some use to you. If you ever have any questions or problems, give us a call through Phillip. I’ll get Iwan to answer them,” I responded.

Iwan flew back to South Africa the following night but I stayed behind to attend a two-day conference entitled ‘Equipping and Supporting Rapid Reaction Forces’ hosted by Jane’s[4]and the British Army. The conference was held over 13 to 14 June 1995 and its purpose was to gather ideas for the formation of the British Army’s soon to be established Rapid Reaction Force.

Taking part were General Alfred Gray Jr (former Commandant of the US Marine Corps), Brigadier JJ Thomson from the British Army’s Joint Rapid Deployment Force Implementation Team, and numerous other senior officers and NCOs of the British Army.

The conference covered:

- Rapid reaction forces: threat scenarios, and roles.

- Air lift capabilities and requirements.

- Rapid reaction helicopter requirements.

- Vehicle requirements for rapid reaction operations.

- Rapid reaction logistics: supporting rapid reaction operations.

I had been asked to deliver a paper on ‘Key requirements for establishing and maintaining autonomous bases’. Drawing on our experiences in Africa and elsewhere, I gave the presentation, answered the many questions that followed, and felt rather flattered by the applause I received. Immediately after delivering my paper, I was approached by a senior British Army officer who asked for a copy of my presentation which I gave to him.

As I was still in the UK, Nico called and told me several journalists were trying to contact me. I took down their names and phone numbers and called them later that day.

Some of them, instead of trying to determine what was actually going on in Sierra Leone, immediately accosted me telephonically, again claiming that ‘undisclosed sources in South Africa’ had informed them Executive Outcomes was committing atrocities in Sierra Leone and then blaming them on the RUF. We were also, they said, taking great pleasure in killing women and children. I was furthermore asked to justify our actions against the ‘freedom fighters of the RUF’ who, according to them, were simply trying to make Sierra Leone a better place for all its citizens. As I was paying for the international phone calls in the hope of setting the record straight, I terminated the abusive calls.

I returned to South Africa shortly thereafter, angry and bitter about the game the media and their sources were playing. They were unwilling to examine the agendas of their ‘undisclosed sources’, and uninterested in following up on claims those sources had made.

Bert Sachse, along with his senior staff, felt that with the pressure on Freetown relieved, it was time to deny the RUF its funding and cripple the movement once and for all. Such an action would also make the government financially viable, enable the restoration of services, place the rebels on the defensive, remove the terror under which the local inhabitants had to live, and show the SLA that the rebels could indeed be defeated. This would, in any future negations, place the government in a position of strength. More importantly, the ordinary people had to be shown that the rebels were not invisible[5]or invincible[6]and could be tracked down and killed.

Planning thus started for a new offensive aimed at taking the war to the RUF, gaining the initiative, increasing the operational tempo, and forcing the rebels to approach the negotiating table, leave the country, or die.

Our men had by now also learnt that the jungle was neutral and favoured those who were willing to exploit it. The initial problems (dense vegetation, limited vision, navigation, restricted movement, and close-range firefights) had been resolved, and the men were ready to take on the RUF on their own turf.

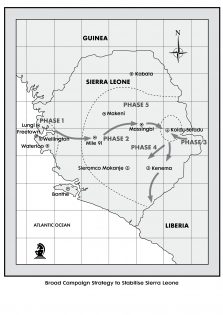

The new broad military campaign envisaged by EO’s planning staff in Sierra Leone consisted of five phases:

Phase 1: Clear the RUF threat to the east of Freetown

Phase 2: Retake the diamond mining town of Koidu, in the Kono district

Phase 3: Dominate the diamond areas and clear the roads towards Liberia

Phase 4: Identify, locate, attack, and destroy the RUF HQ

Phase 5: Conduct area operations throughout Sierra Leone

As Phase 1 had been successfully completed, it was time to commence with Phase 2—retake Koidu.

Koidu,[7]is the capital of Kono district in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone and the country’s fourth largest city with a population of around 100 000 people. Located approximately 430 kilometres to the east of Freetown it is known as the ‘breadbasket of Sierra Leone’ but it is also rich in diamond deposits and mines. The RUF continually targeted Koidu for food and diamonds. The diamonds, of course, paid for their war and it was rumoured that (aside from the illegally mined stones being moved to South Africa) these were of great interest to Colonel Gaddafi of Libya. In close proximity to both Guinea and Liberia, Koidu also gave the rebels access to routes—other than through Freetown—via which to export their diamonds.

Include Map: Broad campaign strategy to stabilise Sierra Leone

The SLA had once had a force there, but it had been isolated and vulnerable to attack. When, finally, their men had extricated themselves from the rebels’ grip many had been forced to return via neighbouring Guinea. Others had fled into the jungle. Their journey home to Freetown had taken more than two weeks, and their departure had left the local population once more in the grip of fear and firmly under RUF control.

Lafras told me about the plan to recapture Koidu in late-May. I knew that we would again be targeted by a media who seemed to delight in every opportunity to vilify the company, but every effort had to be made to interrupt the rebels’ source of revenue, and stop them from brutalising the local inhabitants. Retaking Koidu and stabilising Kono District would accomplish just that.

Bert, Duncan, Roelf, and some senior staff, oblivious to the numerous disinformation campaigns being directed at the company in South Africa, put their heads down, devised their operational designs, and agreed to a course of action for retaking the town. By late-June 1995, their plans had been formulated and they were soon signed off by the president and Brigadier Maada Bio.

The operation, due to commence on 24 June, required an advance of approximately 450 kilometres into the interior—an area the SLA had long since ceased to venture into. The virtually impenetrable jungle would preclude an advance over a wide front and restrict movement to the few existing roads.

A 50-man EO team would lead the advance and attack on Koidu. Joining them would be Fred Marafono,[8]an ex-British SAS sergeant and a Fijian national. Fred, although not employed by EO, was known as a man who could keep his cool under very adverse conditions. He also knew his way around, having lived in Sierra Leone for some time, and had offered his services as a guide. An SLA force of two infantry companies under the command of SLA colonel Tom Nyuma, NPRC secretary of state for the Eastern Province, would follow the force and act as their reserve.

The EO force that would carry out the operation was tiny compared to the much larger rebel force that dominated Koidu Town and surrounds. They had at their disposal, two well-used BMPs, two fairly dilapidated Land Rovers, a few dodgy Bedford trucks, and a Nissan Safari commandeered by an SLA commander and his bodyguards. Two low-bed vehicles were contracted to move the BMPs closer to the objective by road to save their tracks. Support weapons were sorely lacking: the force had one 120mm mortar, an 82mm mortar, and two improvised 60mm patrol mortars. The air assets that would support this force included the two Mi-17 utility helicopters and the Mi-24 attack helicopter.

Despite having to ready themselves for an advance across treacherous and restrictive terrain with such a small force, the men were buoyant and confident about being able to overwhelm and take their objective. Duncan estimated that the combat force would require at least 14 days to conduct its advance, secure the route, and seize Koidu from the RUF. The planning staff were also well aware that security leaks from within the RSLMF[9]HQ in Freetown would reveal the axis of the advance to the rebels who would no doubt lay numerous deliberate and hasty ambushes en route.

Then, the unexpected happened.

The Springbok rugby team had made it through to the Rugby World Cup final and was due to play the deciding match on 24 June—also D-Day for the commencement of the advance. To our men in Sierra Leone, it would not do to advance on Koidu without at least knowing the result of the game. The NRPC gave permission for the operation to be delayed by one day so that the men could watch the game on television. D-Day was shifted to 25 June.

Early on the morning of what we considered to be a great rugby day, Lafras asked me what I was doing that afternoon.

“Nothing much. I guess I’ll watch the Rugby World Cup final on TV. Why?”

“I just happen to have a spare ticket for the match—if you are interested.”

I didn’t need a second invitation. Along with Tony Buckingham, who was passing through en route to Namibia on business, we watched the Springboks beating the All Blacks, and Francois Pienaar, the Springbok captain with President Mandela alongside him, hoisting the World Cup above their heads. It was a moment to treasure.

In Sierra Leone, members of the British High Commission joined the EO men in front of the television set and cheered the Springboks on to victory.

Early on the morning of 25 June 1995, final orders were issued at the Benguema Training Camp(BTC) and the force commenced its advance on Koidu at 06:00. The advance was commanded by Roelf, with Renier Hugo as his second-in-command. Renier led the small vanguard with Fred Marafono (also known as ‘Fearless Fred’) beside him, but Fred’s reckless approach to doing things quickly led to disagreements. Roelf was forced to intervene and advise Fred that the advance would move at the speed determined by EO—and no one else. Fred reluctantly accepted this and matters between him and Renier soon improved.

As the column headed towards the interior, civilians came out of hiding to encourage the men and cheer them on. Others quickly tried to link up with the convoy to travel along to Koidu as the road had been quiet and unused for some time. Thundering overhead and giving top cover was the Mi-24 gunship piloted by Carl Alberts and Arthur Walker, seeking out targets of opportunity before returning to land at Makeni, refuel and await strike orders from the advancing force.

It was surmised that RUF sympathisers had already warned the rebels that a force was on its way to retake Koidu and relieve the pressure in the Kono district.

To speed up the tempo of the advance and discourage ambushes along their route, Roelf decided to drop a mortar bomb or two onto anticipated ambush positions to force the rebels to expose themselves prematurely. Where this was not possible, the men reconnoitred defiles for possible rebel ambush positions on foot.

Rebel movement was observed ahead of the advance approximately 20 kilometres east of Massingbi. The terrain afforded the RUF numerous opportunities to lure the force into an ambush, and isolate, bind, and overwhelm it.

Renier directed the gunship onto the target and all hell was let loose as the Mi-24’s Gatling gun ripped-off 4 000 rounds per minute at the rebel ambush position. It caught the rebels by complete surprise. This was rapidly followed up with an AGS-17 grenade strike. The ambush position was quickly decimated and followed up, and Renier’s forces dismounted for an assault with the BMP-2s delivering fire support, the latter having already been off-loaded from the low-bed transporters. The panic-stricken rebels were pursued by 82mm mortar fire.

The rebels had prepared their ambush with approximately 100 men, of which 15 were confirmed killed. Blood trails indicated that many more had been wounded, and abandoned weapons and ammunition littered the ambush position.

Unable to stop and conduct a thorough search of the ambush area, the force continued to Massingbi, arriving there in the late afternoon.

I was soon thereafter notified of the situation and the progress of the advance. On hearing that EO had suffered no casualties, I heaved a deep sigh of relief.

A tactical HQ was established at an old school that had been burnt down by the RUF, and that was where our men bedded down for the night. An SLA infantry company was tasked to guard the nearby town. That night, during a heavy downpour, an SLA officer warned our men that they were going to encounter heavy RUF resistance the following day and could expect the rebels to inflict heavy casualties on the advance and the men of EO. One of the men later told me that he had considered this comment to be a warning that the SLA were going to run back to Freetown when the first shots were fired.

On the morning of 26 June 1995, the order of march for the advance was confirmed. Orders were issued, and once more it set off for the next objective, an isolated SLA garrison in the town of Bumpe.

Every defile and likely ambush position was reconnoitred and cleared of rebels before the advance continued. On many occasions, the Mi-24 was at hand to provide close air support or to strike identified or potential rebel positions. Roelf’s cautious approach would not only save the lives of EO and SLA men, it would also claim several rebel lives.

One of the men later recounted the first contact they had that morning:

The RUF, lying in wait, did not expect the cautious approach decided on by Roelf.

The small reconnaissance team quickly located the rebels’ ambush position and called in an Mi-24 strike.

Now with Juba at the controls, the gunship flew in low and fast and hit the enemy with the Mi-24’s Gatling gun. Before our men could even get to the ambush position to launch a ground assault, the stunned rebels broke ranks and fled back into the jungle in disarray, hoping to escape the Mi-24’s imminent return.

As Juba circled back to the strike area, he saw the rebels seeking cover in another old and badly damaged school building. He swooped in and devastated them with the Gatling gun. The few survivors fled back into the jungle in a blind panic. By now, EO forces had arrived on the scene and they launched a small follow-up operation on the routed rebels.

Leading the pursuit were Renier and Fred, supposedly supported by an SLA infantry team. When they glanced back, they found that the SLA infantry had decided not to follow them into the jungle, leaving them to do the follow-up on their own. Two men, following a fleeing enemy through unknown jungle terrain didn’t offer the best of odds, so they wisely decided to abandon the follow-up as they couldn’t continue without support. Besides, the jungle canopy was too dense for them to utilise Juba’s gunship—and the RUF were probably running too fast for them to catch anyway.

The ambush position was swept and several bodies and numerous blood trails leading into the jungle were found. In their haste to escape the Mi-24’s onslaught, the RUF had abandoned their dead along with their weapons and ammunition.

Realising that this group of rebels had probably lost their enthusiasm for attacking the column, Roelf ordered the advance to continue. A further seven actions were fought against the RUF that day. At every anticipated ambush position, our men would dismount from their vehicles and sweep ahead on foot with the vehicles ready to race into the area and provide fire support once contact had been made. This was something the SLA had never done—and the RUF had never expected. At each position, the rebels were taken by surprise and numerous bodies were found after each ambush, but Roelf didn’t want to stop and waste time counting the dead after each contact. The bodies were left where they fell for the jungle—or their comrades and wild animals, to claim them.

Along the route, the force passed numerous abandoned, deserted, and burnt down villages. Human life was noticeably absent. Rotting corpses weren’t.

At a bridge crossing some kilometres from Bumpe, a half-hearted ambush was sprung as the lead vehicles crossed a small bridge. The EO team that had dismounted to clear and secure the bridge immediately retaliated with an assault, only to discover that the ambush had been sprung by SLA troops. They soon realised that it was a ‘blue-onblue’[10]contact and fortunately, no casualties were reported. After having received a few deft slaps on the head from SLA colonel Tom Nyuma, the leader of the group, a sergeant, explained that they had, out of fear for their lives, left Bumpe and fled. The threat had been from their own colleagues with whom they had had a disagreement and who no doubt would have killed them had they remained there. The deserters were not sure if the garrison was still standing or if it had been overrun by rebels. They had, on hearing the vehicles, assumed it might be a mobile RUF force approaching. The SLA troops were absorbed into the advance

Shortly before last light, the force neared the road intersection near Bumpe. The isolated SLA garrison greeted them with jubilation—after having recovered from their surprise at seeing white and black men from South Africa working together to affect their rescue. While they were being debriefed, it transpired that there were indications that the RUF had been preparing to launch a large-scale attack on the SLA positions at Bumpe.

A tactical HQ was quickly established on the outskirts of Bumpe. Bert and Duncan were advised of its position by radio and this message was rapidly relayed back to Pretoria. The advance was making far better progress than anticipated. The SLA decided to enter Bumpe and spend the night within the security of the town.

Orders were promptly issued and the men prepared the best defensive positions they could in the fading light. If the RUF were indeed planning an attack on Bumpe, they would get a reception of lead they hadn’t anticipated.

The RUF struck before dawn.

Sleeping in all-round defensive positions, the EO and SLA men were woken by the sound of gunfire erupting in and around Bumpe before first light.

A group of approximately 120 rebels, probably thinking that the force had already passed through the town, launched their attack. The SLA fire they drew, as uncoordinated and undisciplined as it was, seemed to change their minds—as well as the direction of their attack. The SLA, however, managed to kill seven RUF members, and two wounded rebels were captured soon thereafter.

Under fire from the SLA, the RUF force withdrew—unbeknownst to them, directly towards the overnight defensive positions the EO men had prepared and into a fierce barrage of coordinated fire. Although firing back, they tried to disengage and move away but were soon hit with a 120mm mortar bomb. Roelf gave the ‘fire for effect’ order and several more 120mm and 82mm bombs rained down on them. They lost little time in turning tail and leaving the area as fast as they could, leaving the bodies of their dead and dying behind.

The SLA re-joined our men at the tactical HQ and offered them some of their ‘Pega Packs’, a local brew of distilled brandy. They were jubilant about having driven off the RUF attack and wanted to celebrate. Their offers were turned down as a fight still lay ahead. One of our men told the SLA commander, Colonel Tom Nyuma, “We drink after a fight, not before it.”

The withdrawing RUF were rapidly followed up by Renier and two of our men known as ‘Bicycle’ and ‘Gaddafi’. Following them in support was a Land Rover mounted with a DShK machine gun driven by Johan, one of our signallers. That day happened to be Johan’s birthday.

Cutting through the dense jungle, the three men quickly located the RUF force and were surprised to find the unsuspecting rebels casually strolling along the road in single file, rifles slung across their shoulders as though they didn’t have a worry in the world. Our men called in the Mi-24 and coordinated the indirect fire of our mortar teams. The RUF were caught unawares and lost 25 of their men in a matter of minutes.

With the RUF hurriedly leaving the area in total disarray, Juba landed the Mi-24 on the road, handed Johan a beer as a birthday present, and took off again.

As Renier later told me:

It was quite surreal. Here was this contact with the RUF still in progress. There were still bursts of sporadic fire and our mortar guys were still firing their mortars, hoping to kill, wound, or scare the RUF even more. The signaller—I can’t recall his name—was slowly driving the Land Rover along the road to support us and suddenly Juba landed the Mi-24 in the road, gave him a beer for his birthday, then lifted off again to hunt the RUF. I wasn’t really aware of why Juba had landed, so after this mess I walked up to the Land Rover and also wished him a happy birthday.

He looked at me in total surprise and said, “You guys are all fucking mad—stay away from me!”

By then several villagers and some members of the SLA had come running to where the RUF had been caught and killed on the road. To the horror of our men, they immediately started hacking at and mutilating the bodies of the dead rebels. Arriving on the scene, Renier and his men had to threaten the villagers and the SLA at gunpoint to make them leave the corpses alone. After several tense moments, the stand-off ended and the locals and the SLA left the contact area. This was cannibal country and the locals were probably upset about having been denied breakfast.

Meanwhile, Roelf had followed up on a different group of rebels and soon reached the nearby airfield of Yengema without any resistance from the RUF. A stand-off bombardment was launched in the general direction of the RUF’s flight, hoping to drive them deeper into the jungle.

Realising the rebels had now fled the area and would most probably not stop running for some time, Roelf ordered Renier and his men to form up and continue the advance on Koidu.

After a brief stop for lunch, Juba flew ahead and was soon circling over Koidu, reporting that the rebels were leaving the town in droves and fleeing into the hills and the jungle.

Roelf pushed the column hard, stopped short of the town, and sent in a team to conduct a reconnaissance of the area to confirm rebel positions.

As they approached the town, the men were almost overwhelmed by the sickening smell of rotting flesh. They found several severed heads stacked on a traffic circle and there were decomposing corpses in the streets; people the RUF had left to rot where they had fallen. Wild dogs and pigs were eating many of the fresher corpses. Swarms of flies settled on everyone. Such were the horrors of the conflict in Sierra Leone.

Several of the men were physically sick at the sights and smells that greeted them.

On 27 June 1995, Koidu fell without any rebel resistance. The advance had taken three days and, under Roelf and Renier’s command and leadership, had suffered no casualties. Koidu was deserted. While sweeping the town for any rebels hiding there, the men found two destitute and malnourished young boys whose parents had left them in a mosque, hoping that the RUF would leave them alone. A small group of about 15 lepers had also taken shelter in an old church. Malnourished children and lepers were obviously not on the RUF’s menu.

The force quickly set about consolidating its position in and around Koidu, and giving the locals whatever support and assistance they could. Several small security patrols were launched to assess the area and identify potential rebel approaches. Roelf established his tactical HQ on Casino Hill, so named because of a colonial casino that dominated the area. This gave him and his men a good vantage point.

Bert and Duncan were promptly informed that Koidu had fallen. Finding it difficult to believe, Duncan asked Roelf to confirm the report. Roelf reiterated that Koidu was now under the control of the SLA. Duncan had anticipated a two-week operation; it had taken three days.

When the message was relayed to Pretoria shortly thereafter, Nico immediately sent a fax to me in the UK. I, too, couldn’t believe what I was reading and called Nico by phone for confirmation. The RUF, like UNITA at Cafunfu, had now lost one of their primary sources of income. Their ability to continue their war of terror was nearing its end. We had no doubt they would attempt to retake it or extract vengeance on the locals in the area.

*

The news that Koidu was once more under government control was greeted with great excitement and jubilation in Freetown, and people partied and danced in the streets in several cities, towns, and villages across Sierra Leone. President Strasser was equally thrilled to hear the news, as were his officers in the NPRC. Within the ranks of the South African media, EO was condemned for its ‘destabilising activities’ in Sierra Leone. It was again falsely and maliciously claimed that we were being paid in diamonds and had been awarded diamond concessions. The media’s apparent inability to determine the agendas of their sources, as well as verify the so-called ‘intelligence’ they were fed, was astounding.

Oblivious to the adverse publicity EO was attracting, Roelf immediately started mounting aggressive fighting patrols in and around Koidu to stabilise the area and send a clear message to the RUF: “we are here to stay.” Indirect weapons were positioned and fire tasks registered with the mortars. The surviving locals soon began returning to their shattered town, hoping to be able to bury their dead and pick up their lives where they had left off. Team leaders such as Simon Witherspoon, Rich Nicol, and the Du Preez twins, were determined to make sure the rebels got the message and their actions saved the lives of countless innocent locals.

Our men soon learnt just how callously and viciously the RUF had treated the civilians there. A woman reported having fallen victim to rebel activities in early May 1995. They had first fired into her house (wounding her in the arm) and then broken down her door. Why her house had been chosen, she didn’t know. With her were her husband and two sons, as well as a pregnant woman, her two small children, and several young men. The rebels murdered almost everyone in the house except for her and some of the other women who were taken outside and repeatedly raped. After this some of the women were killed. Her daughter was repeatedly stabbed in the back, shoulder, and chest and died a few hours later. The woman’s story was not an isolated one. Some people had been herded into their homes and burnt alive. Pregnant women had been suspended upside down and slit open from vagina to throat and left to die. Others had burning stakes pushed up their vaginas and anuses. Several were cooked and eaten. Many had their arms and legs hacked off with machetes. Suffering a swift death at the hands of the rebels was considered a blessing.

The horrors inflicted on the local population by the RUF were distressing to our men, despite many of them having witnessed the worst that conflict and war can bring.

On 28 June, Duncan flew into Koidu accompanied by members of the Army General Staff and two international journalists.

Despite EO having cleared out a brutal group of cannibalistic murderers, the media, particularly in South Africa, were bitterly angry about this latest blow to the rebels.

The UN was equally concerned about our activities.

Anger and condemnation towards us grew—along with hopes that we would be swiftly evicted from Sierra Leone by the UN or some other force.

The old adage ‘If you stand for nothing, you will fall for everything’ certainly applied to our detractors.

Regardless of what anyone said or intimated, EO had successfully completed Phase 2 of the campaign strategy to clear Sierra Leone of the Revolutionary United Front. Ahead, lay Phase 3—clearing the road towards Liberia—and many more battles with the RUF.

[1]Ironically, in 2017—at the time of revising the original manuscript—the mainstream media finds itself under increasing attack, especially by the newly elected US president, Donald Trump. This has created a growing concern as they are unsure how to regain a semblance of credibility.

[2]The capital and largest city of the diamond-rich Kono District in the Eastern Province of Sierra Leone.

[3]He probably thought thatby referring to the German army as the Wehrmacht instead of the Bundeswehr, we would find more in common with him.

[4]Jane’s Information Group (often referred to as Jane’s) is a UK-based publishing company specialising in military, aerospace and transportation topics.

[5]RUF rebels frequently received ‘medicine’from traditional doctors that was supposed to make them invisible. This ‘medicine’failed the RUF every time they used it.

[6]The RUF, especially their child ‘soldiers’, were given cocaine and amphetamines as a standard feature of their military training.

[7]Koidu’s official name is Koidu–New Sembehun.Also known as Koidu Town.

[9] Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces–The correct designation of the forces. Several of us usually just referred to them as the Sierra Leonean Army.

[10]An accidental contact between friendly forces.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers