By Nicholas Irving with Gary Brozek

You never know how stress and sleeplessness are going to affect you. As we rolled along in the trucks, I was struck by just how beautiful the area was. The moon was up and full, and we’d entered a desert area with rolling dunes. Beauty can also be a beast, or at least it can turn your beasts of burden into two and a half tons of lawn ornaments. The sand wasn’t too deep, the dunes were more like waves of sand, but some of the trucks bogged down. Eventually, it didn’t make much sense for us to try to get any farther on four wheels. We exited the trucks and formed up. So much for all the pre-planning and scouting we’d done. Our target had moved on into an extremely remote and desolate area. Flying in would have revealed our position and intentions, the trucks couldn’t get through, so we were left to our own two feet.

I wasn’t looking forward to the march. I was already exhausted, had catalogued the memories of the assist we gave to the marines in a mental file called “the Longest Day,” and I knew that it was only going to get longer. Yet, when I looked out across the moonlit desert landscape, I thought, This looks like a scene from Aladdin. I wish that Pemberton and I could just ride a magic carpet to our objective.

I wasn’t looking forward to the march. I was already exhausted, had catalogued the memories of the assist we gave to the marines in a mental file called “the Longest Day,” and I knew that it was only going to get longer. Yet, when I looked out across the moonlit desert landscape, I thought, This looks like a scene from Aladdin. I wish that Pemberton and I could just ride a magic carpet to our objective.

The thought and the image were so ridiculous to me that I started to laugh. Pemberton looked at me with a puzzled expression. I managed to stifle my giggle and said, “I can’t even tell you right now what’s going on in my head.”

“I hear you. I’m so friggin’ tired.”

I heard him, but I was still picturing the two of us sitting on that carpet, cruising above the landscape, some corny-ass Disney tune playing in the background.

Five hours later, all I was thinking was that this just sucked. We’d been marching for hours, and it was like we’d been walking in boot-sucking mud the entire time. Those little dunes, the ones that seemed like the ripples on a potato chip, were exhausting. Every step we had to lift one foot up, trying to maintain our balance, and then push off and go, all the while fighting our way through one another’s divots. It was a hamstring-and-quadriceps-killing exercise in stop-motion agony. Worse, the sun was coming up, and that meant that we’d be doing the operation in full-on daytime, having our position exposed in the sunlight.

Every now and then the terrain would change, rocky soil and a few stream crossings, the water just high enough to get over your boots, and the rocks slick enough and the current powerful enough to knock you off balance. Maintaining noise discipline was tough, especially with that many guys; in that high desert valley, it seemed as if sounds could travel miles uninterrupted. We couldn’t talk to each other, obviously, but every time one of us staggered or slipped, we’d involuntarily make some noise, have our gear rattle a little bit. Being stuck inside your own head after that many hours, and being so exhausted and sleep deprived, you were in a place you didn’t want to be mentally. Random weirdness rattled around in there. I took to singing a little song in my mind to keep those other thoughts at bay. In time with my footfalls, I was chanting, “This—sucks. This—sucks,” on and on.

Finally, we got within a half mile of the objective. That’s when the recce team and Pemberton and I split off. We made our way about 800 meters from the main element. I was on point and discovered a large hole, maybe two meters wide and a meter deep. I pointed it out to Pemberton and he nodded. We wanted to mentally mark that location in case we needed it if things went bad. We kept going and then stopped and took our position in a large open field, now some thousand meters from the rest of the platoon. We were responsible for making sure that no one fled the area. The plan had been to check in with the main unit once we’d established ourselves.

I tried my radio. I got nothing in return. Pemberton tried his. Same thing. McDonald tried his. Three for three. We’re lying in the middle of this open field and we’ve got shaky communications at best. Radio malfunctions and radio weirdness plagued us all the time, in a nerve-jangling version of Murphy’s Law.

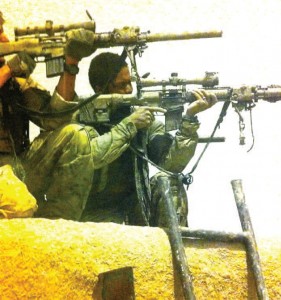

At one point, two men on a bike came up on our position. I had to stop them. I aimed my mounted PEQ-15’s visible laser right on the chest of the guy riding on the handlebars, hoping he’d notice that dot. He did. The bike came to a stop. We were pretty well camouflaged, so I rose up just a bit and signaled to them, making sure to keep the red dot on him, circling it so that he knew exactly where the bullet would impact him. Not a sight anyone would welcome. They took off in another direction, not going back toward the village and not heading toward the rest of our guys.

Pemberton was a few meters away from me, and since our radios weren’t working, he said, “Look. There’s some kind of meeting going on.” He pointed over toward a dead tree where a small group of men had gathered. I watched as they turned inward and then outward toward us, pointing our way. This wasn’t my call, so I got the attention of the nearest recce guy, Derek, a guy who had the habit of sucking in his breath loudly before saying anything.

“Let it play out. Let it play out.”

I didn’t respond, but I kept thinking, this is going to be really bad.

I don’t know how, but Derek seemed to pick up the same vibe as I. A minute after first saying that we should let it ride, he said, “I got a bad juju about this. Let’s get down. Let’s really hunker down. I think an ambush is coming our way.”

I don’t know how, but Derek seemed to pick up the same vibe as I. A minute after first saying that we should let it ride, he said, “I got a bad juju about this. Let’s get down. Let’s really hunker down. I think an ambush is coming our way.”

He was right. A few seconds later, they opened up on us from what seemed to be every direction, a 360-degree spray of AK, RPK machine gun, and pistol fire. They let loose with a few RPG rockets. I remembered that hole we’d seen, and so did Pemberton. We jumped up and headed toward it and Derek followed us. We managed to get into that hole. The rest of the recce guys, including McDonald, were pinned down around the hole. There was no way we could all fit. They’d plastered themselves as low as they could get and rounds were whizzing by our heads, so there was no way those guys could return fire. I’d gotten to the hole first, so I was at the bottom, with Pemberton and Derek both on top of me, one to my left and one to my right. They were able to lay down a few bursts of suppressive fire, but the enemy definitely had fire superiority at that moment.

I couldn’t really get a fix on where the rounds were coming from. It was like we were in a blender and everything was circling around us and at some indeterminate distance. Worse, being on the bottom like that, I couldn’t really see, and suddenly I felt an excruciating pain in my neck and then down toward my shoulder. At first I thought I was hit, but the pain began to dissipate and was nothing more severe than a burn. I knew then that hot brass from my guys’ weapons had gotten inside my shirt.

“Let me up top! Let me up top!”

We were all in a fetal position, clustered like puppies, and were screaming at each other to see if anybody was hit.

Derek was the only guy who had somewhat active comms, but with all the chaos around us, he was having a hard time getting through. I finally managed to crawl my way to the top, and Pemberton and I were up there with Derek underneath us. I could now see, and I wished that I wasn’t able to. The main unit was also coming under heavy fire. I don’t know if it was ours or the Taliban’s, but the sound of multiple grenades going off thumped above the main beat of our weapons. I kept thinking that we shouldn’t have been doing this during the day, and I felt really bad for the second platoon guys. They were just two weeks away from being out of there and now they were caught up in this shit storm.

Derek was the only guy who had somewhat active comms, but with all the chaos around us, he was having a hard time getting through. I finally managed to crawl my way to the top, and Pemberton and I were up there with Derek underneath us. I could now see, and I wished that I wasn’t able to. The main unit was also coming under heavy fire. I don’t know if it was ours or the Taliban’s, but the sound of multiple grenades going off thumped above the main beat of our weapons. I kept thinking that we shouldn’t have been doing this during the day, and I felt really bad for the second platoon guys. They were just two weeks away from being out of there and now they were caught up in this shit storm.

Even from up top I couldn’t spot any targets while scanning. The stalks of native grass were being mowed down and dirt was flying all around us and that rich loamy smell of fresh earth mixed with the smell of gunpowder. About 500 meters away, I caught some motion on top of one of the buildings. Three guys were carrying a machine gun and they were working to set it up. The firing had subsided a bit. I stuck my head up a bit higher, exposing my entire face, and a loud crack sounded. I ducked back down and Pemberton and Derek were screaming at me asking me if I was hit. I told them I was good. Another crack echoed and then the dirt right in front of Pemberton’s face exploded.

“It’s a sniper! It’s a sniper!”

I immediately flashed back to a conversation we’d had with the marines while we were playing poker. They knew roughly where we were going and said we’d better be on our game.

“The Chechen. Watch out for that dude,” one of the guys told us. “He operates in that area. Has like 300 kills or something.”

Since I had just been Reapered and credited with that crazy number of kills, I was a little bit skeptical. The marines added that the Chechen sniper had been around since the Soviet/Afghan days.

“The dude has mad skills and a lot of kills,” a marine said, setting off a round of high fives.

As I lay there in the hole with Pemberton and Derek, I remembered that line and how we’d all laughed. I wasn’t laughing now. But I knew that I couldn’t let that get to me. “Pemberton, I’ve got three guys on top of that building setting up a machine gun nest. We’ve got to get some rounds on that target. I’m going after them.”

“Do it. Just do it.” Pemberton’s voice was high-pitched and it was like you could see a cloud of adrenaline coming out of his mouth as he spoke.

We were all freaking out. “Can you spot me?”

“I can’t frickin’ move. Every time I do—” He didn’t have to finish the sentence. I knew that the sniper was on him.

Keeping my body pressed as tight to the ground as I could, I lifted my weapon over the edge of the hole, pushing the suppressor through the earth. With my torso pressed to the wall of the hole and my legs on its bottom, I slithered up a few inches. I was wishing I could somehow burrow underneath the ground and emerge in a new location like a worm. The next best thing was to get the barrel of my weapon up and out of the ground. I could feel it poking out. I was able to see the top of the building in the scope. I didn’t have time to do any real calculations, but I guessed that they were about 500 meters away. I squeezed off a round and it went high and right of the guy immediately behind the machine gun. I compensated for the elevation and windage and fired again. This one struck the dude right in the shoulder pocket and he went down. As soon as he did, a second Taliban fighter took up the same position, allowing me to fire again without any adjustment. He was easy, but the third guy, who had been moving forward so that he could help feed the ammo, seeing his other two guys shot dead, grabbed a few belts and took off running.

On a normal day, a guy running presented no real difficulties, but with us taking fire and everything else, all I wanted to do, if I couldn’t hit him, was to get him away from that machine gun. I fired off 6–8 rounds, but none of them ever struck home. Worse, as I was in that firing position, a round impacted between me and Derek. I could feel it reverberating through the ground. I rolled over toward Pemberton, and the two of us huddled together, offering whatever cover we could to each other.

“Where’s he at?”

Pemberton raised his head an inch or two and another round impacted danger close. He tried another few times, but the result was the same. “Motherf—er.”

The fact that the sniper was missing us made me believe that he only had a partial fix on us. He could see a hand or a foot or something, but he wasn’t able to zone in on a body, otherwise one of us would have been hit.

The fact that the sniper was missing us made me believe that he only had a partial fix on us. He could see a hand or a foot or something, but he wasn’t able to zone in on a body, otherwise one of us would have been hit.

For the first time, I was at the other end of the scope, and I didn’t like it. It was driving me nuts knowing that some guy was able to fire so precisely on us. What that was doing to us mentally was pretty cruel.

I said to Derek, “We need two sets of eyes. We’ve got to both go up there and check for this dude’s position. We both take a quick look. The machine gunners were at one o’clock. He wasn’t there. Let’s start there. I’ll look right of that, you look left.” Our helmets were no more than three inches apart. As we both nodded that we agreed on the plan, they clanked together. I made the count. One, two, three. We rose up and took a quick look and I could feel a bullet go right between our heads. We dove back down, both of us screaming. Derek’s shout was bloodcurdling and made me think he was hit. We’d made so much noise that a recce medic attached to us yelled in our direction, asking if we were okay. In the brief time we’d been looking for the sniper’s location, I was able to see that the remaining recce element was lying around that field in a kind of star pattern, all of them lying with their arms and legs spread.

I looked at Derek and Pemberton and it was as if their heads had been turned inside out. It was like I could see every vein, every sinew, every tendon standing out. Their eyes were wide and their mouths hung open. Worse, I knew that what I was seeing of them was a reflection of what they were seeing in me. We were in that hole and the combined energy of our collective fear was radioactive. It was like we were in a horror movie where the nuclear fallout was peeling away our skin and revealing our insides. I tried not to think about my wife and my mom and dad, but of course, in telling myself not to think about them, I was thinking about them. I was remembering all the times since getting to Afghanistan when I thought about how cool it was that we were doing the things we had been and what it felt like when I took a guy out, and how ludicrous that all seemed to me just then. I thought of that song I’d been singing in my head—“This—sucks. This—sucks”—the cadence of it and how now it was like those words were jamming through my mind like this: “Thissucksthissucksthissucksthissucksthissucksthissucksthissucks,” in one long, continuous loop. I knew that if I didn’t flip that around, I was going to go nuts, and if I did, then what would that mean for the rest of the guys? I started saying to myself, “I got this,” very slowly and deliberately, and over and over so many times that I started to calm down enough to halfway believe that I was speaking the truth.

I also realized that this wasn’t a situation we were going to be able to fight our way out of. Now wasn’t the time to be the kid who romanticized war and thought about how cool it would be to go balls out over the top in a gung ho charge at the enemy. Now was the time for me to be the calm and calculating chess player. I had a problem to solve, a big one, and I was going to have to think things through and be a thinker and a fighter.

I accepted the fact that since I was the one who’d studied all the sniper tactics; I had to be the one to take this guy out. He was good, and what impressed me was that no one could get a fix on where he was firing from. Everything I knew about countersniping was running through my brain. This was a chess match and understanding your opponent’s position, putting yourself in his shoes, was essential for success.

The Army had taught us the Keep in Memory System (KIMS), and I was used to maintaining a high level of observation. I also knew that we absorbed some information subconsciously and it would come back to us if we were in a receptive state. So I was resting in that hole, closing my eyes, and alternately trying to bring back that entire scene of the village, while also thinking about where I would have chosen to position myself to do what he was attempting to do.

Available on amazon.com

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers