It had to do with an effort to settle the west with camels.

A notorious bandit who plundered California for 20 years may owe his capture to a long forgotten military experiment and an Army camel driver. It had to do with an effort to settle the west with camels.

Bandit’s betrayer may have been Army camel driver

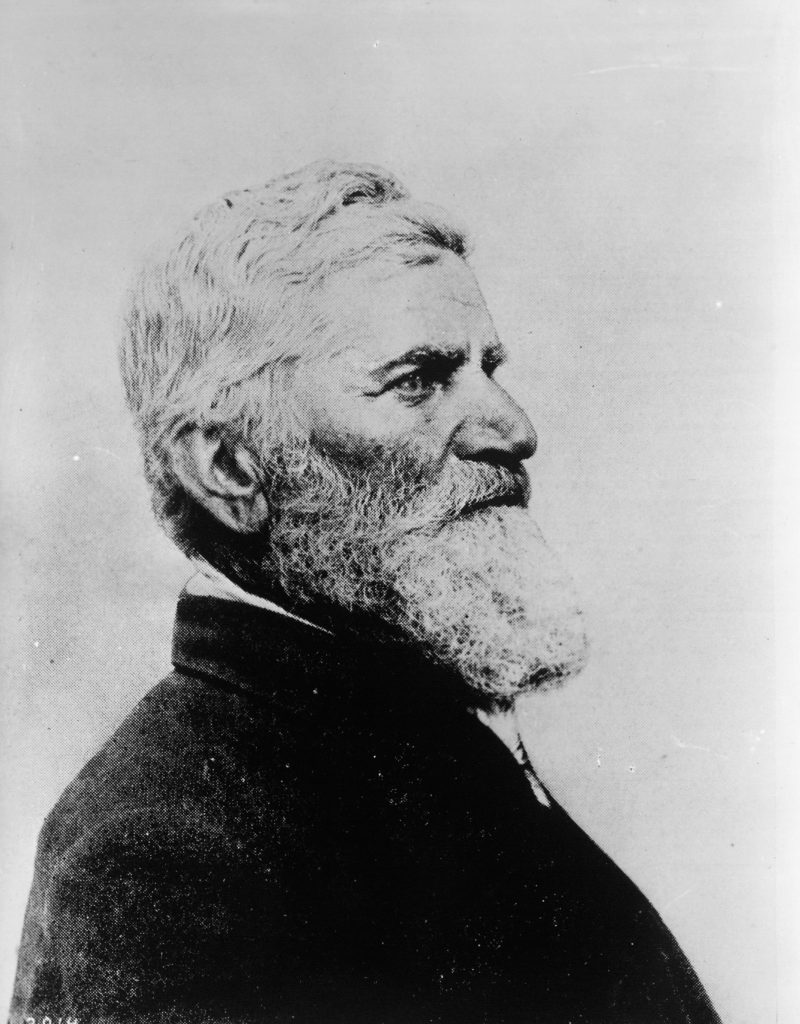

When Tiburcio Vasquez was captured in 1874, he pleaded with others to reveal who had betrayed him. They refused to answer. It was the end of his long criminal career. The following year, he was hanged in San Jose in the state’s last public execution.

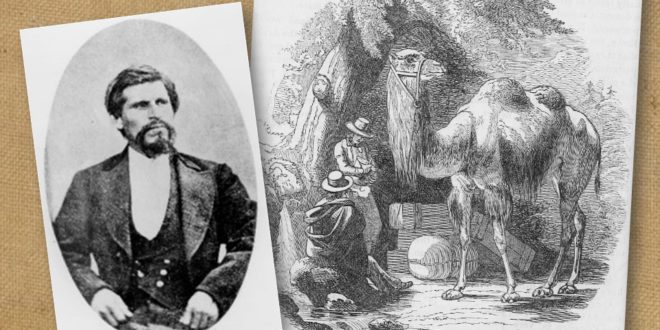

Decades later, a retired lawman revealed the tip leading to Vasquez’ capture came from an immigrant camel driver working for the military. Yiorgos Caralambo, also known as “Greek George,” was close friends with Vasquez.

Caralambo was hired “by the U.S. Army to work for the government from 1857 to 1862 with the Army’s camel experiment,” according to the Montebello Historical Society. While in New Mexico Territory, he allegedly killed a man over a land grant dispute. Rather than face charges, he bribed others to spread the news he was dead, and fled to California.

READ MORE about lore of the Old West

He became a U.S. citizen in 1867, changing his name to George Allen. He unsuccessfully lobbied to received a military pension, or at least a medal, for his time with the Army. Because he was a paid camel driver, and not a soldier, his requests were denied. He passed away in 1913, claiming he never betrayed Vasquez.

Vasquez was no stranger to incarceration

On Aug. 26, 1857, Vasquez was given number 1217 and worked in the San Quentin brickyard to help build the new cell block. Conditions at the prison were less than ideal and he attempted to escape multiple times. Things had gotten so out of hand at San Quentin, California leaders opted to implement strict military rules at the institution.

Released in 1863, Vasquez returned to Monterey. During his years of incarceration, the city and state had changed. Even his family’s property had been sold.

Vasquez publicly avoided taking responsibility for his action, instead blaming others and their attitudes toward him for his criminal inclinations. He slowly built a gang and started rustling cattle in Monterey and Santa Cruz counties.

Bloodshed at the mining camp

He and his gang would often blow off steam at mining camps in Santa Clara County. That’s when his antics caught the attention of Sheriff John H. Adams.

On June 4, 1864, Vasquez and his cousin Faustino Lorenzana were gambling at the camp cantina near Enriquita Mine. Soon, they spotted local butcher Joseph Pellegrini spending more money than usual. They kept an eye on the butcher and when he left the cantina, they followed.

A little after 11 p.m., the butcher entered his shop and went into the adjoining bedroom. That’s when robbers, reportedly Vasquez and Lorenzana, broke the lock and busted into the shop. The butcher grabbed his gun and opened fire, missing his target. The bandits overpowered the butcher, silencing him with multiple stab wounds to his chest. The gunshots were sure to draw attention, so they quickly fled. A few minutes later, when miners arrived to investigate the shots, they found Pellegrini’s bloody body. The shop’s till was empty, missing about $400.

Pellegrini’s death wasn’t the only slaying that night. The next morning, Vasquez gang member Juan Jose Rodriguez was lying dead in a cantina. The bartender, one-armed Julio Almanca, shot and killed the outlaw during an altercation.

Word was sent to the nearby town and the law quickly responded. Sheriff Adams and Undersheriff Richard B. Hall mounted their horses and headed for the camp.

After some questioning, the lawmen were told a “gang of desperadoes” were hiding in the mountains six miles from the scene of the murder. Hall rounded up a posse and headed to search for the hideout.

Meanwhile Sheriff Adams and Dr. A.J. Cory organized an inquest regarding the two killings.

Vasquez hides in plain sight

English was not widely spoken in camp, as the lawmen soon ascertained. One of the few men to speak English was Tiburcio Vasquez. With his reputation and criminal history, he knew he would immediately be a suspect if he fled. So, he opted to stay in camp and even served as an interpreter for the witnesses.

driver hired by the U.S. Army. (Huntington Library.)

Considering the interpreter’s involvement, still unknown to the sheriff, it’s not surprising the inquest yielded no useful information. The sheriff left town, and so did Vasquez. A few days later, the sheriff received a tip that Vasquez and his cousin were the murderers. Without direct evidence, the pair were never charged.

For another two years, the Vasquez gang robbed jewelry stores, stole horses and cracked safes. The locations included Petaluma, Bloomfield, Healdsburg and the surrounding areas. By mid-January 1867, he was back in San Quentin. While in the prison, he managed to reconnect with old business associates. He served until June 1870.

He reportedly visited family, repented his ways and promised to finally go straight but when he heard rumors of a hefty payroll at Firebaugh’s Ferry, the easy target proved too tempting.

A cattle baron and shop keeper become targets

(Courtesy University of Southern California Libraries, California Historical Society Collection.)

Henry Miller, a California cattle baron and half-owner of the Miller & Lux Company, was to be at the ferry on a certain day with $30,000 in payroll. At least, that’s what Vasquez heard. Firebaugh’s Ferry was a stagecoach stop and hotel, with a ferry transporting people and supplies across the San Joaquin River. Today, the town is known simply as Firebaugh.

On Feb. 23, 1873, Vasquez and four of his gang members rode to the hotel and burst inside. Vasquez chose not to cover his face while the others wore masks.

They robbed the seven guests and the hotel owner, then took what they wanted from the bar. The bandits ate, drank and smoked cigars as they waited for the stagecoach to arrive. When they heard the stage rattling up the road, the gang rushed out of the hotel. After securing the stage driver, they broke open the Wells Fargo box and found a bag of coins. Miller wasn’t aboard the stagecoach and neither was his payroll.

Vasquez was sorely disappointed and the next few operations he ordered were said to be his way of redeeming himself in the eyes of his gang.

Tres Pinos fiasco

Later that year, Vasquez and his band headed to Tres Pinos, a small area about a dozen miles south of Hollister. The plan was basic: Half the gang would rob a stagecoach in the remote area near Tres Pinos while the other half held up a nearby store called Snyder’s. When Vasquez spotted an old friend riding on top of the stage, he aborted that portion of the plan. “He always treated me like a gentleman,” Vasquez later recalled as the reason he allowed the stagecoach to pass.

The other half of the gang first played it cool, ordering a few drinks at Snyder’s bar. After a few minutes, pulled their guns and ordered everyone to get down. They bound the hands of customers and the staff.

Snyder’s store was in the center of a small community, complete with other business establishments and road traffic.

Wrong place, wrong time

After securing his sheep in a nearby field, Basque sheepherder Bernard Bahury Hill began walking into the hotel next door. Part of California’s history for centuries, the Basque people came in larger numbers during and shortly after the Gold Rush, often putting their sheep herding skills to use to earn a living.

One of the Vasquez gang yelled at Hill to get down, pointing a gun at him. He apparently didn’t speak English so he fled. Gang member Romula Gonzales chased him, catching the terrified sheepherder trying to climb a fence. Gonzales fired, striking the victim in the face. Badly wounded, Hill staggered toward the hotel. Another gang member, Teodoro Moreno, stepped outside and shot Hill in the chest, dropping him dead on the hotel’s porch.

At about this time, a teamster named George Redford pulled up with his wagon. He was greeted with shouts to get down on the ground with many guns pointed in his direction. He ran and tried to make his way to a barn. Moreno shot him in the back, instantly killing him.

The situation continued to escalate. According to witnesses, Vasquez was frustrated, yelling for his people to stop shooting. Later during his trial he said, “There was to be no bloodshed. … The agreement was to go and rob, not to kill.”

Three people tried to flee into the hotel, where they encountered another bandit. Trying to secure the door against the robber, another bandit walked from around a corner and shot Leander Davidson in the chest. He fell back into the hotel lobby and died. One of the gang members claimed the shot was fired by Vasquez, but he denied killing anyone.

Sheriff Adams back on his trail

By the time the dust settled and their looting was complete, the gang had been in the town for nearly three hours, far too long for Vasquez’ liking. Three people were dead. Loading their mules with ill-gotten goods was taking precious time away from their escape. While the gang focused on securing their loads and organizing a retreat, some of the store customers quietly freed themselves and slipped away to get help.

Once the survivors reached town, notice went out over the telegraph wires. As soon as Sheriff Adams received word of the recent Vasquez killings, he took needed supplies and headed after them. The gang was outside his jurisdiction but he was still in pursuit of the men who slipped through his grasp at Enriquita Mine. The massacre garnered nationwide press as well as the attention of the California governor, who offered a $1,000 reward.

A posse tracked Vasquez down to the La Brea Rancho, where Caralambo’s cabin was located.

Caralambo, who had been keeping quiet all those months, finally tipped off law enforcement regarding Vasquez’ hideout. In the end, Vasquez was executed in San Jose in March 1875 under the custody of Sheriff Adams. At the time, executions were conducted at the county jails and courthouses.

Without the military’s experiments using camels, “Greek George” most likely would not have crossed paths with Vasquez.

What was the camel experiment?

In 1836, U.S. Army Lt. George H. Crosman pitched the idea of using camels to help transport supplies across America’s southwest deserts.

“For strength in carrying burdens, for patient endurance of labor, and privation of food, water and rest, and in some respects speed also, the camel (is) unrivaled among animals,” he wrote, according to the National Museum of the United States Army.

Crosman’s idea finally had a supporter a decade later. In 1847, Maj. Henry Wayne of the Quartermaster Department recommended importing camels to replace mules.

Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis thought idea had merit but could not sway fellow senators. That changed when he was appointed the U.S. Secretary of War in 1853, giving Davis the ability to offer the idea on a broader scale.

“I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of camels and dromedaries for military and other purposes, and for reasons set forth in my last annual report, recommend that an appropriation be made to introduce a small number of several varieties of this animal, to test their adaptation to our country,” Davis wrote in his annual report in 1854.

Congressional approval to purchase camels

The following year, the U.S. Congress approved $30,000 to purchase and import camels and dromedaries for the military.

According to the Army museum, the U.S. acquired 34 animals and hired five people from other countries to care for the animals during the voyage. The foreign employees were also to act as drovers when they reached America. Their 1856 trip home, “slowed by storms and heavy gales, lasted nearly three months.”

On May 14, the camels were unloaded at Indianola, Texas, and allowed to rest a few weeks. On June 4, Maj. Wayne marched the herd 120 miles to San Antonio, arriving June 17.

Davis ordered the ship to return overseas and acquire more camels.

Camel tests

In August, Maj. Wayne began testing the camels, sending them 60 miles to acquire goods in San Antonio. Three mule-drawn wagons each carried 1,800 pounds of oats, taking nearly five days to return to camp. Meanwhile, the six camels carried 3,648 pounds of oats and made the trip in just two days. By January 1857, the ship returned with an additional 41 camels.

The camels were given their first California tests in 1860, based at Fort Tejon. They were used as a messenger service, tested against a mule team. Two camels died on the expedition. According to the military museum, this is the only test the camels failed.

In early 1861, four camels were assigned to a survey of the California-Nevada boundary. The survey team became lost and wandered aimlessly in the Mojave Desert. “After losing several mules and abandoning most of their equipment, it was the steadfast camels that saved the day and led the survivors to safety,” according to the museum.

Civil War ends camel project

When the Civil War started, Davis was elected the president of the Confederacy, and the push to use camels was ended.

Between 1864 and 1866, the remaining camels were sold at auction, many ending up in zoos, circuses or as pack animals for miners, including as a camel-train delivering supplies to Virginia City, Nevada. Unfortunately, the camels weren’t used long. In 1875, the Nevada legislature prohibited camels on public highways to safeguard horse traffic. This effectively ended the commercial use of camels,” according to Online Nevada Encyclopedia, a publication of Nevada Humanities.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur saw one of the camels when he was a child in 1885 in New Mexico. “(It) moseyed around the garrison. The animal was one of the old Army camels,” he recalled.

“Camel caravans were tried for a while between Albuquerque and Los Angeles and elsewhere over the desert land,” noted the Saturday Post on April 19, 1902.

According to reports, the last of the original Army camels, Topsy, died at Griffith Park in Los Angeles in April 1934. The camel was approximately 80 years old.

– The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers