by Fred A. Ganous, SGM, USA (Ret)

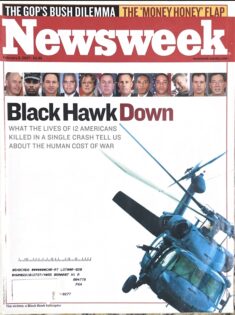

Our deployment in Iraq from 2006 to 2007 was a rollercoaster of emotions, marked by both triumphs and tragedies. The crash of “EASY 40” still stands as one of the darkest days of our deployment.

This UH-60 Blackhawk, bearing tail number 84-23984, was a lifeline for our sister company, routinely flying to deliver vital supplies. Our objective was simple yet critical: keep soldiers off the perilous roads, where the menacing threat of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) lurked. We transported everything imaginable – soldiers, cargo, weapons, and cash – stuffing the Blackhawk to its limits, ensuring delivery under the watchful gaze of the desert sun.

The crew aboard EASY 40 was composed of dedicated individuals, including Captain Michael Taylor, the resolute Company Commander; Captain Sean Lyerly; SFC John Brown; First Sergeant William Warren; and eight passengers, among them National Guard Bureau members visiting the soldiers they commanded.

READ MORE from Fred Ganous: Our ‘Death Angels’ Helicopter Crew Flew Against All Odds in Iraq

That day felt deceptively normal, just another flight over the vast, sunbaked expanse of Baghdad. It was customary for us to fly in pairs—two aircraft working in tandem with Apache helicopters tied up in other missions, EASY 40 and her sister ship would fly without gun support.

I was on the night shift when the tragedy struck. We changed shifts every 30 days, with nights typically quieter – a welcome opportunity for some much-needed rest.

As I readied myself for my shift, there was a knock on my door. It was Sandy – my laid-back platoon sergeant known for his easygoing demeanor – yet tonight, an unusual tension hung around him.

As I opened the door, the gravity of his expression sent a chill down my spine.

“What’s going on, Sandy?” I inquired, sensing the urgency in his tone.

“An aircraft has just been shot down. Grab your gear. We need to move,” he said.

My heart raced. “Who was it? Was it our guys?”

The response was stark: “Yes, but we don’t know who yet.”

We hurried to the Command Post, our hearts heavy with dread and anticipation. It was Robert, our First Sergeant, who ultimately delivered the crushing news:

“It was an Arkansas bird, and there were no survivors.”

The words hung in the air like a fog, leaving me feeling hollow and anxious about who might have been on board.

As the details unraveled, my worst fears were confirmed: First Sergeant William Warren was among those lost. A beloved friend of Robert’s, Warren dedicated himself tirelessly to ensuring the well-being of our soldiers, always prioritizing their needs above his own. The role of a First Sergeant is critical during deployment – sacrificing meals and sleep to oversee the welfare of the troops. Although it was rare for a First Sergeant to take to the skies, the situation demanded it, and Warren stepped up to assist with the flying.

Warren and Robert shared a bond forged in the fires of camaraderie. Every evening, I’d witness them awaiting one another, insisting they wouldn’t eat until both were present. But on that fateful day, Robert found himself alone, a palpable sadness clouding his spirit. As the end of our deployment approached, the focus that had once radiated from him began to flicker and fade.

Sister company Bravo raced to secure the crash site after EASY 40 met its tragic fate. Their helicopters engaged the enemy with precision, targeting those responsible for bringing down our comrades. The hum of rotary blades filled the air as helicopters from both Alabama and Arkansas, part of the 1-131st Aviation Battalion, arrived to search for survivors. Apache helicopters swooped in like avenging angels, ruthlessly eliminating anything that dared to move.

It was clear. EASY 40 was a lost cause, engulfed in flames, a testament to a mission gone tragically wrong. I hold immense respect for those crews who bravely risked everything to protect their fellow soldiers.

Back at the command post, we anxiously awaited the arrival of the returning aircraft. When Bravo finally landed, it was evident they were physically and emotionally drained, each of them carrying the weight of the day’s horrors.

One of the crew chiefs, Joey – a jovial cop from Alabama known for his effortless humor – had been thrown into the chaos of combat. As I helped him clean out his Humvee, empty shell casings from the 7.62mm machine guns littered the floor like forgotten dreams. Joey’s usual spark was replaced with a profound sense of loss, and rather than pry, I simply offered him my silent support.

A memorial service in Balad, soon after the shoot-down.

Eventually, Joey broke the silence.

“Bubba, I shot everything I had. The adrenaline was pumping…I just kept pulling the trigger, even after my weapon was empty.” His voice trembled with anguish, “I shot everything I had, and it wasn’t enough.”

Words escaped me. I had no magic phrases to alleviate his pain, so I stood by and listened, knowing that sometimes, the greatest comfort we can offer is our presence.

The weary expressions on the faces of everyone around spoke volumes, each mark of fatigue bearing witness to the relentless toll that war exacts on the human spirit.

Fred Ganous is a combat veteran of the Iraq war, and has spent his career in aviation.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers