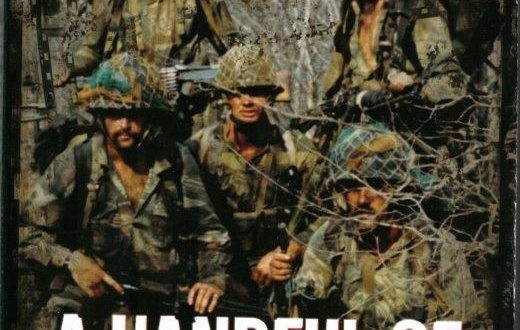

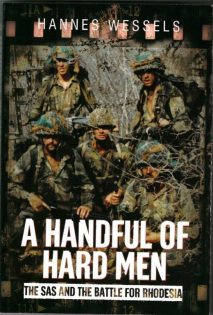

A Handful of Hard Men: The SAS and the Battle for Rhodesia by Hannes Wessels Africa Unathorized

With the collapse of colonialism and the European retreat from Africa the then colony of Southern Rhodesia refused to follow the political fashion of the time and succumb quietly. They decided to take on the world, believing that an immediate transfer of power would lead to tragedy.

War followed and on the killing fields of southern Africa Special Air Service Captain Darrell Watt placed himself at the tip of the spear in the deadly battle to defeat the Sino/Soviet backed forces of Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo.

It is difficult to find another soldier’s story to equal his in terms of time spent on the field of battle and challenges faced. Even by the lofty standards of the SAS and Special Forces in general one has to look very hard and far to find anyone who served in any of these regiments who can match his record of resilience, fortitude and valour in the face of such daunting odds and with resources so paltry.

In the fight he showed himself to be a military maestro. A bush-lore genius, he had no peers as a combat-tracker. Blessed with uncanny instincts and an unbridled determination to close with the enemy and kill he performed in almost every imaginable fighting role; as an airborne shock-trooper leading camp attacks, long range reconnaissance expert, covert urban operator, sniper and saboteur. In all roles he executed his tasks with extraordinary skill inflicting incalculable damage and heavy casualties on the enemy.After 12 years in the cauldron of war he was at the top of his game leading a rebel army on a rampage that was close to snapping the strategic spine of a hostile country when men in suits in far off places stopped him in his tracks and history changed. A soldier’s soldier he did his duty quietly and confidently and sought no glory. Unfortunately some of his political and military peers did not always follow his example.

When the guns went quiet he had won all his battles and lost the war. There was no ticker-tape parade for him, no laurels, no medals and no thanks for death daring commitment to a cause. With only one skill to sell he bade his homeland a sad farewell and went off to fight another war.

In his twilight years, accompanied by his loyal askaris, he has built schools and clinics for poor rural Africans and devoted himself with equal courage and sense of purpose to wildlife conservation. With elephant being slaughtered in unprecedented numbers he is fighting a lonely battle to save the last herds and the wilderness that is their final refuge.

Dazed, fleeing defendants Break from their trenches Into the shrapnelled wall which climbs Where our bombers have passed. We have returned, Rhodesia.– Chas Lotter

Ian Smith’s hopes of finding an international political solution to his country’s problems were fading. James Callaghan, the British premier who had earlier shown a willingness to grovel in the presence of Idi Amin and maintained warm relations with a horde of African dictators, was full of bellicose righteousness when it came to whipping his errant overseas cousins into line. Indeed, he and his foreign secretary would turn up the heat on Smith and increase support for Rhodesia’s foes.

David Owen met with John Vorster in South Africa and asked him to use his influence to force the Rhodesian government to hand over power. The US announced increased assistance for the Marxist regime in Mozambique and refused to pay any attention to that government’s contempt for the basic human rights of its citizens.

Ian Smith could not find common ground with the British Foreign Secretary. “Like virtually all the English politicians I dealt with,” said Smith, “Owen was unable to look at the Rhodesian problem in a genuinely objective way. More important to him than finding a solution, was his desire to punish us. His insistence on handing over the army to Mugabe and Nkomo was nothing more than a scheme to exact retribution on Rhodesians. We had poked the British in the eye and it was his aim to get even. The best way for him to cut our throats was to help Mugabe or Nkomo acquire power. By comparison, Henry Kissinger was a pleasure to deal with. He seemed very genuine in his desire to reach an understanding that took the interests of all into account. I have nothing but respect for him. If the British had approached our problem in the same spirit, I think our history would have unfolded with a great deal less tragedy, but they were terribly vindictive and they took treachery to a new level.”

Andrew Young, the US ambassador to the United Nations, obsessed with matters of race, appeared incapable of impartial reflection, and his lack of detailed knowledge of the pertinent history and complexity of the issues rendered him an ineffective broker. On the record as having called Ian Smith a ‘monster’ who he compared to Uganda’s Idi Amin, he now seemed to have his mind set on a conflict course with the Rhodesian leader. As far as Smith was concerned, the diplomatic initiatives had run their course; the world would settle for nothing less than a government dominated by the terrorist leaders.

Seeking alternatives, he turned to black leaders within Rhodesia to find an internal political solution, and to his security forces to hit the terrorists hard enough to bring their leadership to the negotiating table with constructive intent. However, still fearful of South African power and concerned about providing any additional pretext for further support to the country’s adversaries, he again insisted that collateral damage to neighbouring government forces and installations be kept to a minimum.

The operational commanders and intelligence agents were busy. They were also worried. While many hopes had been pinned on the search for a political solution, they knew that the military threat was growing, with increased material, moral and tactical support from the communist bloc. And to everyone’s dismay, civilian casualties in Rhodesia were steadily rising.

out of necessity. RkB and mercs cased the Rhodesian National Art Museum

with intent of “liberating” valuable art works if Salisbury went up in

smoke after the March 1980 elections. Problem was, they didn’t know what

was valuable and what wasn’t.

It was as a result of intelligence gathered from Renamo operators, along with information gleaned following the Selous Scout raid on Nyadzonya camp, that the rapid growth of two very substantial enemy camps in that country was revealed. A capture retrieved to Rhodesia shed light on location and numbers before aerial photographs taken by an aircraft of 5 Squadron were studied along with first-hand reports from close-in field reconnaissance.

The worst fears of the officers tasked with defending Rhodesia became a startling reality. Experts from the photo-reconnaissance section concluded that the facilities were large in area and housed thousands of potential combatants. One prisoner let it be known that the bulk of the terrorists were ready and merely awaiting the onset of the rains, which would give them the cover to infiltrate Rhodesia. Even rough estimates of the numbers in the camps left operational commanders in no doubt that successful infiltration would be disastrous and, in all likelihood, could lead to the loss of the war and sacking of the country. The insurgency had to be stopped. The question was: how?

The combative Colonel Ron Reid-Daly emerged, champing at the bit with a plan to use his Selous Scouts to demolish the bridges between the camps and Rhodesia, making it logistically problematic for the terrorists to move and at least forestalling their infiltration. However, the plan was not well received with Ken Flower outspoken in his opposition. It was felt that an attack on Mozambique’s infrastructure would evoke more outside calls for intervention on behalf of the enemy.

Not for the first or last time, the generals seemed to be stumped. They turned to their juniors for ideas.

“When I was an officer cadet,” recalled Brian Robinson, “I believed the generals made the plans and gave directives. Not so with us. Unit commanders and their intelligence staff did all the ferreting for information, prepared the plan and then had to sell it to the ‘ComOps’[i] commander and his top advisors. The first presentation of ‘Operation Dingo’ took place in November 1976. It was finally executed on 23rd. November 1977, after twelve revisions.”

Intelligence estimates put the number of potential combatants in the camp that would become known as ‘New Farm’ at between 9,000 and 11,000. Also within the facility was a Frelimo support group, armed with mortars and anti-aircraft weapons. At nearby Chimoio, apart from the Frelimo garrison, there was a company of Tanzanian troops and more than one hundred Soviet advisors. Equipped with T54 tanks, BTR152 armoured personnel carriers and SAM-7 batteries, they would more than likely also have to be dealt with. Tembue, further north, housed an estimated 5, 000 terrorists.

“The obvious plan would have called for a simultaneous hit on both targets,’ said Robinson. ‘However, we barely had sufficient resources to hit a single target, never mind both at the same time. We worked on a forty-eight hour turnaround from Chimoio to Tembue, in the hope that even if the second target was forewarned, we would be able to hit them before they had time to get away. A major consideration was that all internal operations would be left without any form of air support, including ‘casevac’, during that period. The rest of Rhodesia was going to be seriously vulnerable.”

Apart from the potential loss of men, the logistical problems were enormous. This was an army and air force that relied on antiquated equipment which, by virtue of sanctions, was virtually irreplaceable. The stakes could hardly have been higher.

The planners looked forlornly at the odds. One of the first fundamentals that had been drummed into them was that an attacking force should outnumber defenders by three to one. A generation later General Colin Powell, when weighing up the options for war in Iraq spoke of “the principal of overwhelming force as a necessary condition for waging war”. Using Powell’s mathematics 30 000 men would be needed. Rhodesia went in with 185.

A Handful of Hard Men

Do or Die.

On the face of it, it was ‘Mission Impossible’ but the alternative was the possibility the county would be overrun by the enemy. If Rhodesia was to survive, there was no option. Quite simply, it was a matter of do or die. They had to strike, and it had to be soon.

Airborne was the only possible form of transport so the air force would have to provide the pre-emptive strike as well as the transport and support of the ground forces. Every single fixed-wing craft and helicopter in the Rhodesian Air Force would have to be used.

In his capacity as Commander ‘ComOps’, General Peter Walls finally accepted the plan. After much debate and consideration of the political ramifications the green light was given.

‘Operation Dingo’ would decide the immediate future of the beleaguered country, and its successful execution was placed firmly in the hands of SAS commander Major Brian Robinson and Group captain Norman Walsh, Operations Director of the Rhodesian Air Force. Using a huge paper-mâché model, they went to work and fine-tuned the plan.

“I have a vivid recollection,” said Robinson, “of having to give a full verbal briefing to a sea of ‘red-banded cobras’ and ‘blue jobs’ dripping with gold braid, sitting on rugby stands around the model at New Sarum. Trying to look calm and totally confident in front of a very critical and discerning audience required some finely honed theatrical skills. I was followed by Walsh, who presented the air plan.

“The helicopters had a limited range, so a refuelling facility would have to be set up in enemy territory to enable the choppers to complete their tasks. This was known as the ‘admin base’ where fuel, ammunition, medics, first-line reserves and other back-up personnel would be positioned. It would also serve as a medical halfway house for the wounded who would be attended to prior to being ferried home to hospital.

“Setting up an admin area to refuel and re-supply in enemy territory must have been a first in modern guerrilla warfare,” Robinson pointed out. “The idea came from Norman Walsh, a remarkable personality and original thinker who could have been equally at home wearing an SAS beret.

“It was all kept very quiet until the last minute,” recalls Watt. “Only at New Sarum did everyone realise what was going on. A complete security blanket was thrown over us, but when the men saw the amount of ammunition they would have to carry, they knew something big was in the works, but they were simply told to pack, clean weapons and draw their ordnance, then jump onto the trucks to await transport to New Sarum air base. On arrival at New Sarum the troops had confirmation that something major was about to happen. They saw the rows of choppers, the ‘Daks’ lined up and the RLI commandos kitted out and ready.”

Chris Shields, one of the SAS troopers remembers the Orders Group. “At first I thought they were trying to be funny and I think most of us did. There were lots of blokes looking at one another nervously. We were all trying to make some sense of what they were telling us. It took quite a long time to realise this was no joke but we could laugh or cry so all laughed.”

“It was a difficult time,” Watt recalls. “Some were estimating 30% casualties, and expected worse. The odds against us were bad. But they were Rhodesians, and they were very brave. Some of them had just finished selection and were barely out of school, but if you had given them the chance to opt out, I don’t believe a single one of them would have taken it.”

The movement orders preparatory to the raid were exhaustive, with a huge translocation of men and equipment to points around the country.

Intelligence estimates put the approximately 10,000 people at ‘New Farm’ in various stages of preparedness. It was assumed that most of those in residence would be armed and dangerous, though some might be wounded and recovering, while others could be en route to Tanzania and China for training. Women and children were expected to be among the inhabitants. Women, it was agreed, were known combatants and fair game; children were to be spared.

The camp was situated on a farm abandoned by a fleeing Portuguese farmer and covered approximately two square miles. Some of the buildings, consisting of the old homestead, offices, sheds and tobacco barns, had been converted into military facilities, turning ‘New Farm’ into what was effectively the administrative centre for Zanla. There were rooms and offices for Robert Mugabe, Josiah Tongogara, Rex Nhongo and the rest of the organisation’s top echelon, raising hopes of ‘celebrity kills’.

A labyrinth of trenches, revetments and defensive lines had been constructed, anti-aircraft weapons and other heavy weapons were dug in and an early warning system of sentries in towers with whistles was in place. Tethered baboons were strategically placed and watched by sentries. It was believed that their senses were better tuned than those of humans, and any restive behaviour from the animals was to be considered a possible indication of imminent attack.

Surprise was absolutely vital to the success of ‘Operation Dingo’, so the sound of approaching aircraft presented a major challenge. The man who would have to deal with that particular problem was the indefatigable Jack Malloch.

He would fly his DC 8 jet-liner over the camp on the morning of the attack as a decoy, mere minutes before the raid. This shrewd ploy, it was hoped, would provide the vital time needed to mask the sound of the approaching air armada. The big jet would pass over ‘New Farm’ at 07h41, when the terrorists should be on parade. The military strategists banked on them scrambling for the trenches at the sound of jet engines, only to discover it was a commercial aircraft, relax and return to their previous positions. No sooner would they have done so than the fighter planes and bombers would be upon them.

Hawker Hunters of No 1 Squadron would initiate the attack with bombs, rockets and cannon. They would be followed immediately by the Vampires and finally, the Canberras, which would keep the enemy heads down while the paratroopers deployed.

They would jump into action from the ageing Dakotas, while some forty RLI commandos were ferried in by helicopter. The vertical envelopment would cover three sides of the target ‘box’, while the gap would be closed by ‘K-Cars’ armed with 20mm cannon. Coordination of the air-strike and the para-drop had to be perfectly timed. If the helicopters were too close to the target, the noise would give the game away. If the Canberra strike was too early, the ‘paras’ would be shot while still in the air. If the Canberras were late, even by minutes, the paratroopers could hit the ground among exploding bombs.

Once the escape routes were closed, troops in sweep-lines would advance to flush the trenches and gun-pits and kill anyone who appeared before them. Those choosing to flee rather than fight would run into the stop-groups. Machine-gunners were loaded with as many belts as they could carry, with instructions to replenish with looted ammunition when they needed more.

John Ngwenya, one of those who survived the attack, said of the period leading up to it: “I had just arrived from Nachingwea in Tanzania and was awaiting my first mission to Zimbabwe. Our commanders told us the Rhodesians were not to be feared, that they were fearful of us and that because of sanctions, their equipment was old and unreliable and our bases were too far inside Mozambique for them to strike.”

“We were very tightly monitored and spreading any alarm within the ranks of the fighters was a serious offence, punishable by death, so we were all careful of what we said, and to whom. Despite this, I did hear some talk that did not concur with what we had been told by our seniors and instructors. Some of the comrades had been involved in action against Rhodesian soldiers and they had not liked it. The Rhodesians did not run, as we were told, but were aggressive and accurate with their weapons. One told me that the Rhodesian riflemen did not use their weapons on automatic fire as we did. Instead, they fired one or two shots at a time, and they were very accurate, even over a long distance. As a result I was a little apprehensive about what to expect, but there were so many of us and we had so much weaponry at Chimoio that we were mostly of the opinion that they would never attack us there.”

In addition to their own forces, Zanla had its Frelimo comrades close by, and they had tanks and other armoured vehicles as well as artillery and mortars. Ngwenya; “We were agreed our numbers and equipment would dissuade the Rhodesians from attacking us. As a result, I think we were not well prepared when they did come, because most of us just believed it would not happen.

“Comrade Mugabe visited us once while I was at Chimoio and he was very aggressive. He told us the Rhodesians were tiring and we would be victorious, because our cause was just. He told us Marxism gave the power to the people, where it belonged. We were all much cheered after listening to him. I studied my book containing the thoughts of Chairman Mao and believed strongly that the communist system would triumph over capitalism, which was another form of colonialism.”

On the eve of the operation, across the country at Thornhill Air Base outside the central midlands town of Gwelo, the crack pilots of No 1 Hunter Squadron, who would initiate the attack, had been closely studying their ‘AirTask’. Led by Squadron Leader Richard Brand, they were all experienced combat pilots, but they knew the morning of 23 November would bring with it their most challenging mission. Awaiting their arrival were batteries of 23mm anti-aircraft guns, RPG-7 rocket launchers and ‘Strela’ heat-seeking missiles, along with thousands of AK-47s and RPDs. The ground fire was one thing; they would also have to be mindful of interception by the MiGs of the Mozambique Air Force.

They studied the details: the target description and position, the TOT (time on target), the armaments and weapons systems they would be carrying, and copied all the frequencies and ‘call-signs’ they would need to maintain vital communications. Ground crews were briefed on fuel and armaments, time for takeoff and the number of planes. The crews would work into the night to make sure all aircraft were 100 per cent serviceable.

Then the air crews went back to the aerial photographs to study the target more closely, with particular reference to the position of the ‘ack-ack’ guns and the likely prevailing winds, which would affect their weapons delivery. They could only hope that cloud and poor weather would not make the task at hand even more difficult than it was already expected to be. Taking all external factors into consideration, they plotted their attack patterns and ‘initial points’ (IPs), those all-important coordinates at which each aircraft would commence the final ‘run-in’ a mere fifty feet (little more than fifteen metres) above the ground, prior to pulling up to the ‘perch’ from which the pilots would turn in for the attack. Satisfied that they had done all they could, the air crews went to bed, after telling the duty orderly when to kick them out of the covers.

At New Sarum, the Vampire and Canberra pilots went through the same preparations. There were six of the old wooden Vampires left, but only two had ejector seats.

Steve Kesby remembered: “Our squadron was to fly two Vampire T11s and four FB9s. The briefing was held in the parachute hangar and was the most comprehensive for any target to date. The enormity of the strike filled us with excitement and not a little apprehension. The FB9s with no ejection seats were to be flown by ‘Varkie’ Varkevisser, Ken Law, Phil Haigh and me. The northern part of the Chimoio target, comprising the training element, was allocated to the ‘Vamps’. ‘Varkie’ and I were to suppress flak by taking out anti-aircraft weapons, while the others were to take out barrack blocks and other targets[ii].”

When they and the Hunters had completed their initial strikes, the Canberra bombers would pound the camp with a mixture of explosive ordnance.

While the pilots plotted their strikes, there was excitement among the ground crews at New Sarum. Coming from posts all over the country, the operation had brought many of them together for the first time in a long while, and they relished the moment. The Corporals’ Club was designated the meeting place, and after completing their checks they congregated to drink a few beers and catch up on old friends. But at 22h30, the shutters came down and the men in blue went to their billets to await the dawn.

Brian Robinson and Norman Walsh took themselves to the air force officers’ mess to have a drink that evening. They were mentally drained and physically exhausted, but confident that the planning and coordination was in accordance with their wishes. Robinson was especially mindful of the fact that the battle for ‘New Farm’ would be only the beginning. “We then had to extract the men, equipment and parachutes post haste for the next phase of the operation,” he said. Both men felt a natural anxiety that the unexpected could upset the entire plan, but the stark fact was that they had done all that could be expected of them; ‘Operation Dingo’ was now in the lap of the gods, the ‘troopies’ and the weather. They drank a toast to the success of the mission, then had another drink. After that, they went to bed, but sleep proved elusive.

At 03h00, Robinson and Walsh stirred and dressed before joining their officers to see their men in the hangars as they prepared for battle. They did not like what they saw overhead; it had rained and the sky was overcast. Bad weather would dash the best plan and that seemed a distinct possibility.

Troops checked weapons and equipment, fitted their parachutes and strapped rifles into place, then checked one another. Ready to go, most smoked cigarettes while waiting for the order to board. Bad weather notwithstanding, they were going to go for it; the survival of the country as they knew it lay in their young hands, and youthful eyes showed some of the strain. The banter of the previous day had been stayed and men went quietly about their business, each alone with his thoughts and fears.

Andrew Standish-White, a farmer’s son from Sinoia, vividly recalled that morning. “The hum of voices, the snapping of clips being tested and fitted, that funny sweet smell of the parachutes, the nausea of one too many the night before…the morning chill causing shivers that were desperately suppressed, lest anyone watching thought it was from nerves…needing to take a bloody pee after being fitted and checked – what a pain it was to get to the necessary ‘apparatus’! Collapsing in a heap on the jump mats to wait…and wait…and thinking that maybe, very soon, you would be ‘jumping to a conclusion’. Everyone was thinking about dying but trying not to let on. Fiddling with your weapon – was the gun tight enough behind the shoulder? Was the pistol well secured but still easily accessible? Should you stow the metal feeder strip of the RPD belts in the webbing pouch or have them protruding for instant access? The smokers all had to bugger off outside once fitted – no smoking in the hangar. Heaps of them stood outside, puffing hard on their cigarettes.”

At Thornhill, Richard Brand’s men entered the crew room to sign off their individual aircraft before he led them across the tarmac to the waiting aircraft, poised and primed like steel predators of the night.

Brand was continuing a proud tradition. The scion of a venerated family of fliers, his uncle Sir Quentin Brand was a pioneer of African aviation who had been first officer on the first aircraft ever flown to Rhodesia. In March 1920, the converted Vickers Vimy bomber named the ‘Silver Queen’ II had landed on the racecourse at Bulawayo, introducing commercial aviation to the young colony.

Now, fifty-seven years later, a heavy burden lay on the young shoulders of Sir Quentin’s nephew. His squadron’s strike had to be precise and devastating. His point of impact would be the marker that the other pilots would follow. It was on Brand that the planners were relying to hit the enemy very fast and very hard, putting them to flight from which they would be given no respite. If his aim was off, the enemy would have the chance to brace and fight, and that eventuality could prove calamitous for the ground troops. The pressure to perform had never been greater.

Brand greeted his ground crew and they wished him luck. After completing a thorough pre-flight check, he climbed the ladder and lowered himself into his cockpit, secured his helmet and microphone, carried out his final checks and fired up the engine. As always, the feel of bridled power gave him strength and confidence. He taxied out to the runway threshold with the remainder of Red Section in tow. As he requested clearance for take-off, he noticed a little light in the east as the sun sought to break the day and give them the visibility they would need to fly and fight and kill the enemy that threatened their country.

At New Sarum to bid his pilots and crews farewell was Air Marshal Frank Mussell, the air force commander. General Peter Walls climbed aboard the Dakota from which he would monitor radio traffic and remain in contact with the prime minister on a tele-printer. Ian Smith wanted to be kept informed and would make decisions of a political nature. Of concern was what to do if Mozambique committed troops and armour and how to deal with the MiGs of the Mozambique Air Force, if they were scrambled from their base in the port city of Beira.

Darrell Watt stood on the runway smoking a cigarette and looked anxiously skyward, searching for a break in the wet, grey, gloom. He knew better than most how critical timing was, and that if the weather was overcast when they reached the target, the operation would probably fail. He tried to hide his concerns, kitted up and chatted briefly to his troops, then ordered them into the waiting Dakota. They moved quietly to their positions on the hard metal bucket-seats that lined the fuselage. Final permission granted, virtually the entire Rhodesian Air Force roared into life while soldiers and airmen strapped themselves in and girded themselves for battle.

The helicopters were airborne first, flying almost due east in waves of five for security reasons. The bush telegraph among the local population was known for the speed at which information was conveyed by word of mouth, and the sight of an aerial armada would trigger a quick response from hostile observers, that might be communicated to the enemy in time to warn them of approaching danger.

The Dakotas, laden to the maximum with fuel and heavily equipped men, used up all the distance the runway offered before lumbering slowly aloft. Soon they were all airborne, following carefully selected flight paths to avoid, as best they could, being noticed by too many on the ground.

The further they flew, Watt’s apprehension deepened. “It was just cloud and more cloud. I could only hope the navigators were on the ball; they certainly had their work cut out for them, and I did not envy them their task.”

Breaking the silence in one of the Dakotas Sergeant Smash, unable to control himself, started to sing ‘Happy, Happy Africa!’ which soon caught on and the pilots were treated to a raucous chant to their rear.

At the same time, seated quietly at the controls of his DC 8 was the stocky figure of the old warhorse, Jack Malloch. Headset straddling a balding pate, he listened closely to the radio traffic for any indication that his unauthorised incursion into Mozambique airspace was being challenged. If that happened, he was utterly defenceless against the MiGs; but that, he knew, was the nature of the game.

Squadron Leader Harold Griffiths led the formation of thirty helicopters flying line astern, map-reading his way down the valleys leading to the target. All of a sudden they were in cloud, and his heart must have stopped as he realised that he had to backtrack and map-read a new route to the target area, without losing a second. In a remarkable feat of airmanship, he did just that, handling his controls while reading a 1:50 000 map in an open cockpit. Behind him was the command chopper, flown by Norman Walsh with Brian Robinson sitting next to him.

Estimating that he was over the target at 07h41, Malloch opened the throttles for maximum power and lowered the flaps to increase the noise factor. The ruse worked. Unseen by him, blinded by cloud, the terrorists were on morning parade and the sound of the aircraft triggered an air-raid warning, sending the entire camp scurrying to the trenches and bunkers. Realizing soon thereafter that it was a false alarm, they relaxed and returned to their stations, a little warily, but relieved.

NEXT PART II : THE ATTACK

The book is available AT: https://www.amazon.com/Handful-Hard-Men-Battle-Rhodesia/dp/1612003451

http://exmontibusmedia.co.za/EMM/shop/

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers