by Austin Lee

It was one of the ballsiest clandestine ops in history: Project Azorian, the CIA mission to snatch a Soviet submarine from the Pacific Ocean’s crushing depths. The haul from the Golf-II-class K-129 was a priceless score for the Americans. The mission also prompted a rare act of Cold War brotherhood, and spawned a phrase that became iconic in spook-speak: “We can neither confirm nor deny.” Here’s how it all unfolded.

The submarine sank in March 1968, roughly 1,500 miles northwest of Hawaii. It plummeted to a mind-boggling 16,500 feet, taking with it a vault of Soviet treasure. This included nuclear-tipped torpedoes, cryptographic gear, and potentially game-changing codebooks. The Soviets couldn’t find the wreck, but the U.S. Navy pinpointed the precise location, using deep-sea acoustics and recon from the USS Halibut, a nuclear sub turned spy platform.

The CIA wanted to recover the sub; but how would they accomplish such a daunting feat?

Enter Howard Hughes, the eccentric billionaire with a penchant for aviation, Hollywood, and, as it turns out, playing ball with spooks. The CIA tapped Hughes to front a cover so wild it just might work. The story was that his company, Global Marine, was building a deep-sea drill ship to mine manganese nodules – potato-sized mineral deposits – from the ocean floor.

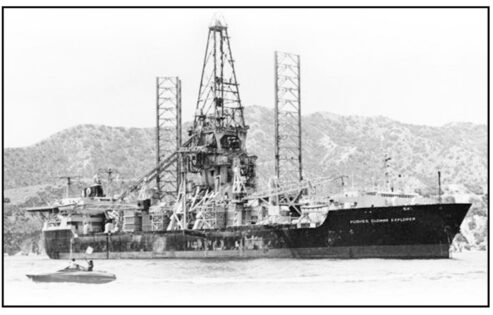

(The Glomar Explorer. CIA photo.)

Howard Hughes was no stranger to the shadowy world of intelligence. By the late 1960’s, the reclusive tycoon already was a legend; aviator, filmmaker, and industrialist with a sprawling empire that included Hughes Aircraft, a key defense contractor. His ties to the CIA ran deep, dating to the 1950’s when his companies provided tech for recon projects like the U-2 spy plane. His mystique made him the perfect frontman for Azorian. Hughes was exactly the kind of eccentric who’d chase a harebrained deep-sea mining scheme. The CIA leaned on his reputation as a maverick in order to sell the manganese mining ruse, knowing the Soviets would buy it.

The manganese nodule cover story was a stroke of genius, cloaking espionage in the dull sheen of capitalist ambition. In the 1970’s, deep-sea mining was a plausible frontier. Manganese nodules, rich in nickel, copper, and cobalt, were hyped as the next big resource. The CIA crafted a meticulous fiction: Global Marine was developing the Hughes Glomar Explorer to vacuum these nodules from the ocean floor, a venture backed by fake scientific papers and industry buzz.

The ship’s public specs – derricks, drilling rigs, and a high-tech processing plant – aligned with this yarn, while its true purpose remained hidden. In reality, this 618-foot behemoth was a custom-built leviathan designed to hoist a 2,000-ton submarine using a massive claw dubbed “Clementine.”

READ MORE from Austin Lee: The 6.02x41mm: Russia’s Answer to NATO’s Body Armor

The secretive magnate’s Summa Corporation worked closely with the Agency, in conjunction with Global Marine. Lockheed Missiles & Space Company engineered the Glomar Explorer’s covert systems. Hughes himself stayed hands-off, leaving the heavy lifting to trusted aides, but his name gave the op a veneer of plausibility.

The Soviets, wary but not suspicious, kept their distance, buying the story hook, line, and sinker.

The retrieval process was a feat of engineering that would make even the saltiest frogman whistle. The Glomar Explorer, crewed by a mix of CIA operatives, engineers, and unwitting merchant mariners, sailed to the wreck site in July 1974. The ship’s centerpiece, Clementine, was suspended by a string of pipe segments strong enough to lift a small skyscraper. Lowered through a moon pool – a massive opening in the ship’s hull – Clementine was designed to grab K-129 like a carnival claw game, albeit one played at three miles deep with 1,500 atmospheres of pressure.

The op wasn’t flawless. During the lift, a mechanical failure caused two-thirds of the sub to break apart, sending critical missiles and codebooks back to the abyss. Still, the team recovered a 38-foot section, including two nuclear torpedoes, crypto gear, and the remains of six Soviet sailors.

Soviet sailors being lowered into a burial vault.

The sailors were given a solemn burial at sea with full military honors – a rare nod of respect in the Cold War shadows. The ceremony included prayers in English and Russian, and featured the flags and national anthems from both countries. According to Cold War lore, Soviet Premier Boris Yeltsin was so moved by the video that it brought it him to tears.

The mission secrecy blew up in 1975 after a burglary at Hughes’ Los Angeles office led to leaks in the Los Angeles Times. In response to questions from journalists, the CIA coined the infamous Glomar Response – “we can neither confirm nor deny” – a phrase that’s now a hallmark of spook-speak.

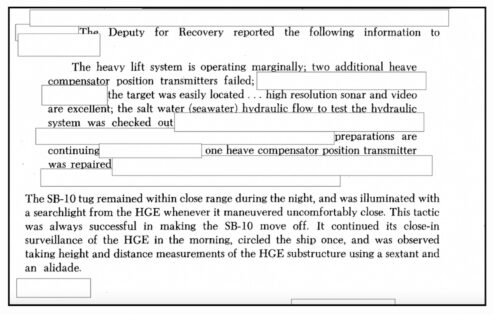

Aspects of the mission remain classified, with significant segments of the CIA final report still redacted from public view.

Project Azorian’s legacy looms large in the annals of clandestine recovery. It wasn’t the first time the U.S. went fishing for enemy tech – think of the Navy’s 1950’s efforts to snag Soviet cables or the 1966 recovery of a hydrogen bomb off the coast of Spain – but Azorian’s scale was unmatched. Its audacity paved the way for later ops, like the Navy’s 1980’s missions to tap Soviet undersea cables using modified subs, or the ongoing hunt for advanced tech from downed drones and satellites.

A portion of the CIA’s final report on Project Azorian. CIA document.

Costing a cool $800 million (over $4 billion in 2025 dollars), Azorian was a high-stakes gamble blending cutting-edge engineering with Cold War espionage, all under the nose of the Soviet Navy. Its technology – from precision lifting systems to stealthy design – influenced deep-sea recovery methods still in use, though modern ops lean on unmanned submersibles and AI-driven mapping.

The mission’s partial exposure in 1975 didn’t dim its shine; it showed the world that the CIA could dream big, even if it meant losing a few secrets—and a chunk of a sub—to the deep.

Azorian’s real triumph was its proof of concept: with enough cash, brains, and balls, you could pull off the impossible, even under the Kremlin’s nose.

For the spooks and grunts who pulled it off, Azorian remains a badge of honor, a harpoon shot across the bow to the Soviets, delivered from the ocean’s darkest depths.

Austin Lee is the proprietor of Galilhub, and is a gunsmith and a competitive shooter. He writes frequently for Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers