“Remember The Alamo!”

The battle was a 13-day siege that began Feb. 23 and ended March 6, 1836.

David (Davy) Crockett was one of the most famous figures of his day. Born in Tennessee in 1786, Crockett had many adventures in his youth as a frontiersman and military scout. In the 1820s, he entered Tennessee politics and eventually served two terms in Congress. His reputation as a sharpshooter, hunter, and storyteller grew with his success, and many fanciful accounts of his life were published, both by Crockett and by those seeking to capitalize on his fame.

By 1835, Crockett had become disillusioned with politics and set off to explore Texas, departing Tennessee with the famous quote: “You may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.” Crockett fell in love with Texas and joined the volunteers in the fight for Texas independence. He died at the Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836.

One hundred eighty-nine men from 23 states and seven countries that included England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Denmark, Germany and Mexico brought Jim Bowie, William Travis and the legendary David Crockett to the Alamo to defend her against the Mexican Army led by Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

All were killed U.S. Army

Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna Recaptured the Alamo

March 6, 1836

On the morning of March 6, 1836, General Santa Anna recaptured the Alamo, ending the 13-day siege. An estimated 1,000 to 1,600 Mexican soldiers died in the battle. Of the official list of 189 Texan defenders, all were killed.

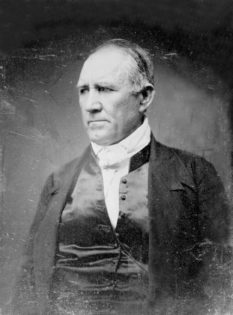

On April 21, 1836, Sam Houston, commander of the Texas Army, led 800 troops in a surprise attack on Santa Anna’s 1,600 men. Shouting, “Remember the Alamo!” the Texas Army won the battle at San Jacinto in 18 minutes and secured Texas independence from Mexico. Texas remained independent for nearly 10 years, becoming a state in 1845.

Background from Texas: One of the most gallant stands of courage and undying self-sacrifice which have come down through the pages of history is the defense of the Alamo, which is one of the priceless heritages of Texans. It was the battle-cry of “Remember the Alamo” that later spurred on the forces of Sam Houston at San Jacinto. Anyone who has ever heard of the brave fight of Colonel Travis and his men is sure to “Remember the Alamo.”

Besieged by Santa Anna, who had reached Bexar on February 23, 1836, Colonel William Barret Travis, with his force of 182, refused to surrender but elected to fight and die, which was almost certain, for what they thought was right. The position of these men was known but no aid reached them. The request to Colonel James W. Fannin for assistance had gone unheeded. No relief was in store. As the Battle of the Alamo was in progress, a part of the Texas Army had assembled in Gonzales under the command of Mosely Baker in the latter part of February. From this army, a gallant band of 32 courageous men under the command of George C. Kimble left to join the garrison at the Alamo. Making their way through the enemy lines, these 32 men joined the doomed defenders and perished with them.

On March 2, 1836, during the siege of the Alamo, Texas independence was declared. Four days later, the document was signed with the blood shed at the Alamo. It was under such conditions that Travis and his men fought off the much larger force under Santa Anna. It was with the love of liberty in his voice and the courage of the faithful and brave that Travis gave his men the none too cheerful choice of the manner in which they wished to die.

Realizing that no help could be expected from the outside and that Santa Anna would soon take the Alamo, Travis addressed his men, told them that they were fated to die for the cause of liberty and the freedom of Texas. Their only choice was in which way they would make the sacrifice. He outlined three procedures to them: first, rush the enemy, killing a few but being slaughtered themselves in the hand-to-hand fight by the overpowering Mexican force; second, to surrender, which would eventually result in their massacre by the Mexicans, or, third, to remain in the Alamo and defend it until the last man, thus giving the Texas army more time to form and likewise taking a greater toll among the Mexicans.

The third choice was the one taken by the men. Their fate was death and they faced it bravely, asking no quarter and giving none. The siege of the Alamo ended on the dawn of March 6, when its gallant defenders were put to the sword. But it was not an idle sacrifice that men like Travis and Davy Crockett and James Bowie made at the Alamo. It was a sacrifice on the altar of liberty. The Defenders listed with bio

The Battle of the Alamo

Image: William Barret Travis. From October 1835, Texans in the field had succeeded in most of their military campaigns. The cannon at Gonzales remained, smaller military units surrendered and then retired to Mexico, and Bexar finally gave way after a two-month siege. When Martin Perfecto de Cos and his men retreated from Bexar in December 1835, Texas had eliminated the last of the Mexican garrisons.

Image: William Barret Travis. From October 1835, Texans in the field had succeeded in most of their military campaigns. The cannon at Gonzales remained, smaller military units surrendered and then retired to Mexico, and Bexar finally gave way after a two-month siege. When Martin Perfecto de Cos and his men retreated from Bexar in December 1835, Texas had eliminated the last of the Mexican garrisons.

Most of the volunteers returned to their homes, convinced the war was over. The provisional government, split by internal quarrels over the objectives of the war, failed to supply the men in the field adequately. What little remained of the munitions and supplies were further subject to confiscation by commanders proposing buccaneering expeditions to Matamoros.

By January, the small body of men commanded by James C. Neill were reduced to about 100. They were supplemented by some twenty-five volunteers commanded by James Bowie. William Barrett Travis arrived on February 3 with thirty men from the regular army, ordered there by Governor Henry Smith.

In spite of engineer Green B. Jameson’s belief that the Alamo was indefensible, both Neill and Bowie saw the fortress as a strategic post, particularly because of its armament. Houston, on the other hand, preferred to avoid fixed fortifications, and ordered Bowie, subject to Henry Smith’s approval, to blow up the building.

When James C. Neill left the city a few days later to deal with illness in his family, he left Travis in command. Bowie, however, as commander of the volunteers, refused to accept orders from a regular army officer. A divisive contest was avoided when Bowie became ill and was forced to accept the arrangement.

Image: D. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Santa Anna crossed the Rio Grande on February 12, and – a month earlier than expected – he arrived outside Bexar on February 23. Travis dispatched a note to Gonzales calling for reinforcements and numbering the defenders at 150. The next day he wrote his Letter from the Alamo, probably the best known of all Texas documents.

Image: D. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Santa Anna crossed the Rio Grande on February 12, and – a month earlier than expected – he arrived outside Bexar on February 23. Travis dispatched a note to Gonzales calling for reinforcements and numbering the defenders at 150. The next day he wrote his Letter from the Alamo, probably the best known of all Texas documents.

Reinforcements under Captain Albert Martin arrived from Gonzales on March 1. With the arrival of the last of Santa Anna’s forces, Travis was able to send out only one last appeal on March 3. Again, he echoed the determination of the fortress to withstand surrender: “A blood red banner waves from the church of Bejar, and in the camp above us, in token that the war is one of vengeance against rebels: they have declared us as such, and demanded that we should surrender at discretion, or that this garrison should be put to the sword. Their threats have had no influence on me, or my men, but to make all fight with desperation, and that high souled courage which characterizes the patriot, who is willing to die in defence of his country’s liberty and his own honor..”

After the battle, the Texan bodies were burned. The pyre was constructed about three o’clock in the afternoon of March 6, and was lighted about five according to Francisco Antonio Ruiz, who went on to report: “The gallantry of the few Texans who defended the Alamo was really wondered at by the Mexican army. Even the generals were astonished at their vigorous resistance, and how dearly victory was bought..The men (Texans) burnt were one hundred and eighty-two. I was an eyewitness, for as alcalde of San Antonio, I was with some of the neighbors, collecting the dead bodies and placing them on the funeral pyre.”

After the fall of the Alamo in 1836, the church and buildings were largely abandoned. The government of the Republic returned the chapel to the Catholic Church, but after annexation, the U.S. Government claimed it again for military use. In the ensuing years, both U.S. and Confederate forces used the building to house quartermaster stores and munitions. The U.S. Army continued to lease the property until 1876. Bishop John Claud Neraz’s offer to sell the Alamo in 1882 was made to Frank W. Johnson, first president of the Texas Veterans’ Association. He, in turn, passed the information on to the governor with a recommendation that the State purchase the building. On April 23, 1883, the Texas legislature passed an act authorizing the purchase of the Alamo. Money from the sale went to complete a new chancery building for the San Antonio diocese.

Image: Fall of the Alamo, by Theodore Gentilz

Image: Fall of the Alamo, by Theodore Gentilz

Related Battle of the Alamo topics from this online exhibit:

William Barrett Travis’ Letter from the Alamo

David Crockett

James Butler Bonham

Santa Anna’s Account of the Battle

Election return from the Alamo, February 1836

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers