by John Gartner

As I sat looking out the port side window of the Dakota, I could see below me the vast expanse of Lake Cahora Bassa dam. The grey skeletal branches of long-drowned trees dotted the shoreline and seemed, in my reverie, to be reaching imploringly skyward. The surface of the water reflected the rays of the emerging day. As always, imagination running wild in these situations, I was nervous, my mouth dry and heart racing, as I anticipated the approaching parachute descent on to yet another ZANLA encampment in Mozambique.

I stood up and hooked up to the static line, checked my equipment and looked around at my SAS comrades. The nervous anticipation was evident. It was never easy to wait for the word to go in such situations, every moment seemed prolonged and there was little attempt at chatter over the noise of the engines. Red light on, green light on and I slid from the door. With canopy deployed, I methodically searched the ground below. At eye level, I could see the Canberra bombers in their low-level attack. Dust billowed in a line below the aircraft as their fragmentation bombs exploded in the enemy camp.

I struck a tree heavily as I came into land, and felt the breath knocked from my body, but in the adrenalin charge of the moment, I recovered quickly and disentangled myself from the restrictive parachute harness, freed my AK47, and moved into my position in the assault line, facing the enemy camp. Moving forward, I searched the bush for targets. As I approached a small stream, I heard a sudden shuffling in the riverbed. Heart pounding, I jumped down onto the sand and immediately saw two men running.

As I gave chase, I called loudly to the assault line above me, obscured by bush, warning them that I was below in the riverline. I had no desire to be on the receiving end of any friendly fire.

Burdened with my equipment, panting from the injury I had sustained to my ribs on landing, and with the riverline meandering in front of me, I had no opportunity to aim and fire before I lost sight of my quarry. I emerged from the river and rejoined the assault line, in time to hear the crackle of small arms fire a short distance away. The two fleeing guerrillas were gunned down as they emerged into open space.

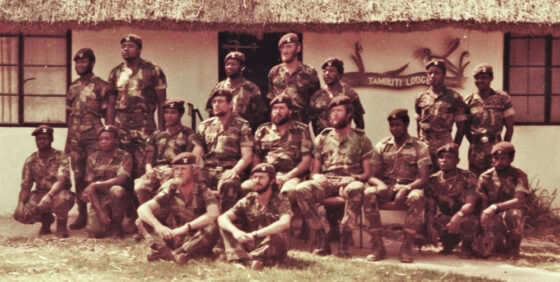

The author, center back, with Rhodesian Selous Scouts “Recce Troop”

Moving closer to the heart of the camp, I heard a moaning in the bush immediately to my front. As I peered ahead, I saw a camouflage figure lying face down in the long grass. Our eyes locked momentarily, I raised my rifle to fire, and then looked more closely at what confronted me. This was the first female combatant I had encountered in this war, though rumours abounded that there were hundreds in the ranks of the ZANLA Army. It was generally believed that they provided comforts of a more intimate nature, rather than acting as fighters in the field.

Certainly, I had never heard of any woman being killed or captured in any firefight in Rhodesia or Mozambique before this day. Now here in front of me was this mortally wounded woman.

My breathing was becoming increasingly difficult, the pain from my chest allowing nothing more than quick and shallow breaths as I made my way around the huts. Finally, the pain in my chest became unbearable and while others searched the camp, I sat down on the ground, my back resting against a tree. When flames started to rise from the huts, I moved with the remainder of the SAS troops south from the perimeter of the camp towards the helicopter LZ.

I was by now well and truly in difficulties, unable to stand upright, the pain sharp in my chest. I had to leave the clearance of the LZ to others.

The following morning, back home in Salisbury, I could barely move from my bed. Taken to Andrew Fleming Hospital by my wife, X-Rays showed the extent of the injury I had received, three broken ribs and severe bruising. My chest was tightly bandaged, this was the best treatment I could expect, and I was sent home. When I reported the results of my hospital visit to the SAS doctor, he placed me on light duties, which I welcomed for the unexpected opportunity it presented to spend some time at home with my family, free for the moment from the threat of another sudden deployment.

Towards late 1976, the acting CO of the SAS, Major Mick Graham, wanted to stamp his identity on the unit while he had temporary command. He decided that reconnaissance operations into Mozambique needed to be intensified in view of increasing ZANLA activity. I certainly could not dispute his appreciation of events, as Rhodesian security forces were stretched like the proverbial drum. The Rhodesian African Rifles, the Territorials and the Rhodesian Light Infantry had their hands full, and manpower was limited by an ever-decreasing supply. We in the SAS seemed to be forever on operations, and R & R was becoming a luxury.

Not only were we literally outgunned by our enemies, with their unlimited resupply lines, we were also desperately undermanned and could never hope to match the manpower resources of ZANLA and ZIPRA. We were under attack without respite from Zambia in the north, and from Mozambique in the east, and to aggravate the threat even further, northeast Botswana, along the road running from Kazungula, on the Zambezi River which marked the Zambian border, to Francistown in central Botswana, had also started to provide another ZIPRA incursion route, this time into western Rhodesia.

Combined Operations in Salisbury, in liaison with the Commanding Officer of the SAS, decided to infiltrate an SAS reconnaissance team deep into Mozambique, to chart enemy activity and to interdict ZANLA reinforcements well before they approached Rhodesian territory and while their guard was down.

As a test of previously unused concepts, and in typically zealous fashion, the SAS was instructed to assemble a reconnaissance patrol of four men, to infiltrate by means of HALO freefall technique, which we had yet to utilise operationally. I had done my freefall course two years earlier but had yet to use it for the purpose intended when I had undergone the training.

The author training Sri Lanka’s Special Task Force, which protected the President, Prime Minister and all Cabinet members.

Unfortunately, at this stage of the development of the SAS, there were still too few freefallers and I happened to be one of those few. Not having undergone a freefall descent for some time, I was nervous at the prospect of any jump, let alone an operational insertion, but understood that any insertion by helicopter risked early compromise, particularly as the targeted area of operation would be at the furthest range of the Alouette’s fuel capacity. I must admit that there was also a certain element of glamour to the concept of a pioneering freefall operation, which slightly alleviated some of the tension I was experiencing.

I was still recovering from the injury to my ribs and could have used this to excuse myself from the approaching operation. The SAS doctor certainly sympathised with my predicament, knowing that good freefall technique required an arched back and widely outstretched arms.

As always, duty called loudly and clearly, and feeling far from noble, I told him that I felt capable of doing the jump.

Due to the sense of operational urgency, our team had insufficient time for a rehearsal jump to refamiliarise ourselves with the technique, and within what felt too short a time, we arrived laden with our patrol equipment at Parachute Training School at New Sarum, from where we were to embark in the Dakota. To compound my growing anxiety, the air force jump despatchers decided that we would have to jump without the automatic opening devices that we normally used for every freefall descent. I had always jumped with an AOD, and though it had never been needed in the past, it always offered some feeling of comfort, knowing that, though unlikely, if I lost consciousness during the freefall descent, my parachute would nevertheless open at 2,500 feet above the ground, regardless.

Sanctions made it difficult to replace such items should they be left behind in the bush at the end of the operation. I shrugged mentally at this decision, feeling far from happy at the prospect ahead of me now. With haversacks, patrol harness, Tactical Assault parachutes and rifles stowed aboard the aircraft, we had a final confirmatory briefing with the pilots, and then climbed aboard. I made myself as comfortable as possible in the spartan interior as the Dakota taxied to the main runway and took off, climbing slowly towards our jump height.

Though HALO freefall technique incorporates a personal supply of oxygen that attaches to the individual freefaller’s parachute harness, things were rough and ready in Rhodesia, equipment was always scarce due to sanctions, and improvisation was the rule. In this case, we used a hospital oxygen cylinder, attached to the floor of the aircraft, with individual tubes running to each of the freefallers and the two despatchers. Rudimentary, of course, but quite adequate for the circumstances. The pilots had their own independent oxygen supply.

As our height increased and the air became thinner, I placed my mask over my face, trying to relax. It was difficult, especially knowing that I had no AOD to rely on. My nerves were stretched taut and I yearned for a cigarette, not possible of course with oxygen in the aircraft.

As we approached our jump height of 15,000 above ground, in effect 20,000 above sea level, the air grew colder, and my heart started thumping vigorously.

From this height, I could see the sun finally setting, its last weak rays illuminating the sky, but as I looked below, I could make out little detail in the gloom of a typically African last light. The ground appeared little

more than a solid blanket of bush, interrupted occasionally by meandering riverlines, dry and sandy.

As the aircraft lined up on its final approach to our jump point over Mozambique, the four of us, under the command of Sergeant Andy Chait, stood up and prepared ourselves, patrol harness pulled on first, parachute next, rifles tied securely to the left shoulder, haversack pulled into position snugly and securely against the back of the thighs. We took up positions at the door, oxygen masks held in place, hoses snaking along the floor to the cylinder. Andy Chait was first in the door, leaning well forward. I was immediately behind him, anxiously peering over his shoulder into the darkness. We were arriving late over target and were ill prepared for a night descent, with no personal guidance lights worn on our helmets to pinpoint our individual positions once we were freefalling.

The weight of my haversack, the restrictive tightness of the parachute harness and reserve, the discomfort of my AK47 strapped tightly behind my left shoulder, all added to the pressure on my still tender ribs.

I stared at the dispatcher as I awaited the thumbs-up signal to go. When it came at last, I threw

myself after Andy Chait and looked up at the belly of the aircraft as I fell away. Turning and tumbling despite my perfectly arched freefall position, I lost sight of the other three members of the patrol.

As I slowly came into a stable facedown position, my arms widespread, the wind howling past my helmet, I searched below, but could see no other freefaller. I was alone in the sky but too preoccupied with the task at hand to worry too much, at least for the time being.

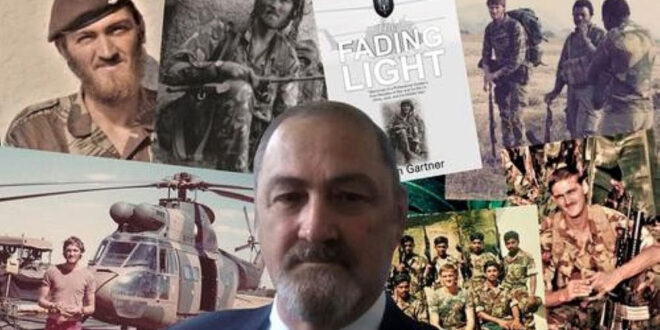

This story is an excerpt from Gartner’s book, The Fading Light.

John Gartner is an Australian born former Australian SAS Regiment soldier who enlisted in the Rhodesian SAS in 1974. He served throughout the duration of the Rhodesian bush war (1974-1980) before leaving Zimbabwe to serve in South African Special Forces. He transferred to the National Intelligence Service, and served with the Sri Lanka defense establishment before forming his own Private Security Company to work across Africa, SE Asia, and Iraq.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers