by Susan Katz Keating

“There’s a certain sound…”

The song stuck with him for years afterwards. He was being marched to his execution in the jungles of Vietnam, and had been ordered to carry a radio to pick up “Radio Hanoi,” but he secretly dialed in to a station that picked up American music. It came through without a hint of static: The pop star Petula Clarke was singing “Happy Heart.” And that, Nick Rowe told me, gave him a sense of good things to come. He wasn’t sure what it meant – but on that day in 1968, the young Green Beret officer held on closer to his pet, a little dove he’d befriended while in captivity, and continued marching forward at the point of the Viet Cong rifles.

“I can’t explain it,” Rowe told me years later, when I knew him while writing for Soldier of Fortune. He and I spoke often in those days, when the SOF crew, myself included, were hunting the trail of POWs in Vietnam. Rowe wanted to know the truth about missing Americans, and he shared what he knew about the Viet Cong and their methods. That included telling me his own experiences in captivity.

Of that day when he was supposed to die, he told me, the song was like a flag; and he paid attention. “Something was coming,” he said. “I just knew.”

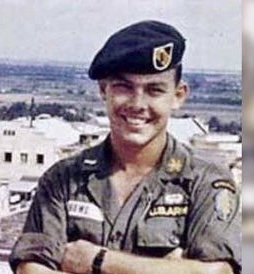

Throughout his life, James “Nick” Rowe knew about things that were coming, eventually including the attack that killed him in 1989. But not even the prescient Green Beret could have known the impact he would have on soldiers who succeeded him in Special Forces, and throughout special operations.

Now, years after his April 21 death at the hands of a Philippine communist hit squad, Rowe is a near-mythic figure whose name is spoken with reverence.

Rowe was the son of immigrants who lived through the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. He grew up in the small town of McAllen, Texas. His older brother, Richard, attended West Point. When Nick was six years old, Richard died shortly before graduating. Nick vowed to fulfil Richard’s military destiny.

Rowe kept his childhood promise. But shortly after he graduated in 1960 from West Point, the premonitions began. For three consecutive nights, he dreamed he was captured during a firefight with Viet Cong guerrillas.

Two years later, the nightmare came true. While serving in the Mekong Delta, Lt. Rowe was captured by Viet Cong on Oct. 29, 1963. Also captured were Captain Humberto “Rocky” Versace and Sergeant Daniel Pitzer.

Rowe mostly was kept apart from his team mates, in the notorious U Minh “Forest of Darkness,” in southernmost Vietnam. But, Nick later told me, he sometimes encountered them and other American prisoners of war. And he often heard Rocky singing patriotic American songs, or arguing with the guards in perfect Vietnamese.

Rowe spent five years inside small jungle camps in South Vietnam.

During that time, the Viet Cong believed Rowe’s cover story that he had been drafted into the Army, and that he was an engineer assigned to build schools, bridges, and various other civil affairs structures.

“They tested my story by giving me engineering problems to solve,” Rowe said. “I’d taken classes at West Point, and I had a very basic knowledge of engineering. It was enough to convince them.”

Still, Rowe faced a struggle to survive.

“We had every disease vector in the world there,” Rowe told me in a 1987 interview. “We were on two quart cans of rice per day. We caught snakes and rats every chance we got.”

He caught beri beri. He had dysentery, and was covered in fungus. For punishment, the guards would withhold what little food they allotted to him. They took away his mosquito net.

Rowe was kept in a cage made of slender saplings, measuring 3 feet by 4 feet by 6 feet. He tried to escape three times but was recaptured and punished each time.

In 1968, activists from the American “peace” movement inexplicably revealed the true identities of many POWs – including Rowe. The enraged captors planned to kill Nick, just as they had killed Rocky.

Nick’s execution was set to take place on New Year’s Eve. As the Viet Cong escorted Rowe to the killing field, the Green Beret heard Petula Clarke on the radio.

As the song began with the words “there’s a certain sound,” Rowe heard what he called “the familiar and most welcome music” of Huey and Cobra helicopter blades, beating the air in flight.

The helicopters then seemed to appear out of nowhere. In a burst of action, Rowe knocked down one of his guards. He ran into a clearing, waving his arms.

A soldier in one of the helicopters at first thought that Rowe, wearing black pajamas, was an enemy guerrilla, and nearly shot him. But Rowe’s beard identified him as an American. The helicopter rapidly descended, low enough for Rowe to dive aboard.

“Go! Go!” Rowe shouted.

As the helicopter whisked him away, a the copilot yelled for him to spell out his name. In shock mixed with overwhelming joy, the copilot asked: “Are you Nick Rowe?”

The Americans had been searching for him for five years. In his absence, he was carried as missing in action, not killed – and was promoted to major.

When finally he reconnected with his parents, Rowe apologized to his mother for being gone so long.

“I tried, Mom, but they just wouldn’t let me go,” he told her.

Rowe switched to serving in the Army Reserve. In 1981, he was recalled to active duty, to help form the Special Forces Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) course. The course teaches soldiers to evade capture but, if caught, to survive and return home with honor.

“We took all the lessons we learned the hard way and incorporated them into the curriculum,” Rowe told me. “We don’t want anyone going through on-the-job training.”

Later, Rowe was assigned to the Joint U.S. Military Advisory Group in Manila. While there, he wrote me letters asking me to help with an effort to award Rocky Versace a posthumous Medal of Honor. He called me at work at The Washington Times, to ask if I were making progress.

He told other friends – particularly the Montagnard indigenous forces he had grown close to – that Rowe, now a colonel, had another premonition. He was on a hit list, he said. He believed he would be assassinated.

The premonition came true. On April 21, 1989, the 51 year old Rowe was killed in a hail of gunfire on a Manila street. The round that took his life entered his car through a slight crack in an air vent, an investigator later told me. The communist New Peoples Army took responsibility for the murder.

The Special Forces community was stunned by Rowe’s death. Green Berets cried openly on the streets of Fayetteville, N.C., home to Fort Bragg. Another friend, an American military intelligence officer, wrote to me from the Philippines to say his unit was in shock.

“We are all reeling from the news of Col. Rowe’s assassination,” my friend wrote.

Many who know of Rowe continue to speak of him with awe. His legacy is the SERE course, widely credited as the most important advanced training in the special operations field. Other sites are named in his honor, notably the “Nasty Nick” obstacle course on Camp MacKall.

More than three decades after his death, Rowe’s gravestone at Arlington National Cemetery shows evidence of the visitors who come to pay their respects. Rocks, rose quartz, and unit insignia are left by visitors, to remind Rowe’s spirit that he never will be forgotten.

Susan Katz Keating is publisher and editor in chief of Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers