by John Spencer

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt of the book “Connected Soldiers: Life, Leadership, and Social Connection in Modern War” published by Potomac Books and available for purchase at Amazon here. The excerpt describes 2LT John Spencer’s experience jumping into Iraq as a platoon leader with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in the opening days of the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

After finishing our rigging up, we took all the gear off again. This is not as ridiculous as it may sound. It was important that we got everything organized for departure first. By the time that was completed, it was time to eat. We left our gear and parachutes lined up where we had been, with soldiers guarding it, took our weapons with us, and were bused to a “chow” hall on base. There we walked in and saw something none of us had ever seen in the military, nor would we ever see again.

The entire dining hall was full of food and included dozens of giant carts overflowing with full-size lobsters, huge T-bone steaks, corn on the cob, baked potatoes the size of a fist, and a wide variety of desserts, like giant pieces of chocolate cake—it was all you could eat. This was not the military we knew! It took only about three seconds for everyone to close their dropped jaws and relate what they were seeing to the famous scene in the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers, where the paratroopers are served ice cream before the big jump on D-Day.

“They never serve us ice cream. . . . This is a death meal. That’s it, it’s a death meal.” Death meal or not, we ate like we were starving, and we loved it. If it was going to be our last meal, we were going to enjoy every last bite.

It was not our last meal. Those who were able slept the night on cots in an airplane hangar and woke to more “ice cream” treatment. They brought us breakfast that was again historic—more than we needed of biscuits, sausages, bacon, eggs, hash browns, orange juice, and more. We did not even have to get bused to the chow hall this time. They delivered it to us. Again this was something that never happened unless we were in the field on a training exercise.

Once our “death breakfast” had filled our bellies, we returned to the airfield, finished getting our gear sorted, and put it on again. The mood was different. We knew that the next time we unstrapped from the gear, our parachutes would have deployed in the sky over Iraq, and we would have landed in the combat zone. This was getting very real.

“Thirty seconds!”

Twenty minutes out, the plane started a violent descent into Iraq airspace. We had been flying at a higher altitude so as not to be within range of missile fire from the ground. For the jump, we dropped to below one thousand feet, not very high in terms of parachute jumps, to minimize our descent time under the parachutes and our exposure to enemy fire.

At ten minutes out, the jumpmasters shouted the warning, “Ten minutes,” and everyone shouted it back as the butterflies in our stomachs tried to fly out. At six minutes, we received the command to “Stand up.” We stood up and faced the rear. Upon hearing the command, “Hook up,” we then clipped our static lines into the anchor line above us that ran the length of the aircraft. This was followed by commands to check the static lines and check our equipment one last time.

READ MORE from John Spencer on the situation in Ukraine.

The air force crewmen opened the doors on both sides of the plane, letting the cold air rush in—or maybe the cold feeling came from inside me. Then the jumpmasters were allowed to take their positions in the doors.

The last two shouts were, “One minute!” and “Thirty seconds!” That meant it was time for our sphincters to pucker. My mind rapidly reviewed the technique for safely exiting the aircraft, and my body reviewed the muscle memory of the action. This was one time I absolutely had to execute the technique correctly. In between those thoughts, I reminded myself of what had to be done tactically once I was on the ground. I had a lot on my mind, as everyone else must have too. Many of them also must have been thinking of their wives and kids—not a distraction I had, although maybe some of them found those thoughts to be inspiring, more motivation to return home safely.

As the number one jumper on my side of the aircraft, I had the questionable pleasure of standing by the then open door as we approached the DZ. I had to stand there and watch the jumpmaster do his checks: meticulously planting his boots on the inside of the doorframe, then stomping his foot on a small walkway that gets dropped out the door, then firmly gripping the inside of the door. He leaned out into the void, the wind blasting him as he looked ahead trying to spot the DZ. No biggie, right? There are not a lot of jobs that require you to lean out of a flying cargo jet. If his grip slipped and he tumbled out early, he would be lost and alone somewhere in a war zone.

Because of my experience serving as the jumpmaster on other flights, I knew what he was going through, but my own mind was racing in so many directions, plus there was the pain of trying to stand even for five minutes with that weight hanging off me awkwardly. It was very painful! It might seem odd, but my mind and body wanted out of that aircraft. A parachute weighs thirty pounds on your back but does not weigh anything when it is floating above you.

The checks the jumpmaster was doing “had to” be done several times before we actually got to the DZ. Considering the sophisticated navigation equipment the pilots had at their disposal, the checks were likely an archaic holdover, but who was I to question the ritual?

No hesitation is authorized

The time finally arrived. On March 26, 2003, at approximately 1945 hours Zulu time, 12:45 a.m. local time, the green light came on, the jumpmaster yelled, “Go!” and hit me on my backside. My training kicked in. No hesitation is authorized, and I instinctively stepped out the door. My feet landed briefly on the ledge outside of the door and then my body, hitting the gusting wind, was sucked out into the air. There are two exit doors on the C-17, so on the opposite side of me there was another jumpmaster and line of anxious paratroopers waiting to exit the aircraft.

READ MORE from John Spencer on his trip to Ukraine with Liam Collins to study the battle of Kyiv.

One second after I was slapped, my counterpart experienced the same. This created a staggered exit of the jumpers while both sides dumped their cargo of anxious paratroopers. The staggered exit of bodies is an amazing act of coordination and science that with a naked eye looks like a constant stream of projectiles. Paratroopers almost always use the exit doors on the side of an aircraft instead of the rear ramp because the exit doors allow for more soldiers to get out quickly. That is the ultimate goal of a combat jump: get as many soldiers out of the aircraft and safely on the ground ready to fight as quickly as possible.

When I exited the aircraft, the sounds were overwhelming due to the engine noise and turbulence. We were required to wear earplugs because it was so loud. In addition to the sound, the jet blast of the massive C-17 pummeled me and sent my body tumbling through the night sky, violently throwing me about. Once my chute opened and the plane was a distance away, there was dead silence.

I immediately took out my earplugs, letting them fall into the black void below me. Still I heard not a single sound. There was no feeling of descent, just a sensation of hanging in midair. I was alone with my thoughts—not all good thoughts. I wondered how fast I was falling and when the brutal impact of the ground would come, an impact I had felt in more than forty training jumps.

For tactical reasons, we jumped on a moonless night. While this meant the enemy could not see us, it also meant we could not see below us as we fell rapidly toward the ground. I had a twist in my risers, the straps connecting my harness to the parachute, that kept the parachute from opening as broadly as it should. Theoretically this causes a faster descent and harder landing, but I was on the ground quickly so it did not concern me for long. The landing was surprisingly soft after all.

As we were taught, I kept my feet together and rolled when I touched down, distributing the impact over five points of contact: balls of my feet, calf, thigh, buttocks, and “pull-up muscle” (the latissimus dorsi, or the muscle below the shoulder, on the side of the back). Oh, who am I kidding? I landed in a heap and miraculously was uninjured.

It took less than a minute for 954 soldiers of the 1st Battalion 508th Infantry, 2nd Battalion 503rd Infantry, and the 173rd Headquarters staff to exit the fifteen C-17s and another minute or so to hit the ground. We did not have time to ponder the historical significance of the event. We were American soldiers just dropped into a combat zone and had things that needed to be done.

I worked quickly in silence to collect up my parachute, putting it in a kit bag with the reserve chute and empty weapon case—— having removed my M4—and leaving the bag in place. This was another sign of combat because in training jumps soldiers must carry those cumbersome parachute bags to a central collection point. Within minutes I had the bag filled, my weapon in hand, and my ruck onto my back.

Where was everybody?

That may sound like a quick process, but it always felt like it took longer than it should, even more so when time was of the essence. Having just done a combat jump, though, I was pumped with adrenaline as I headed to where I thought the linkup point should be. In the silence, there was no way of calculating time, and I feared I was going too slowly. I really had no temporal sense. But I said, “Screw it,” and pushed onward. In the darkness, I could not see other soldiers and certainly did not want to be a straggler. Even when I was able to put on my night vision goggles, I could not see anyone else. Crap, where was everybody? We must have been more spread out than I would have guessed. The darkness, terrain, and silence completely hid us from each other.

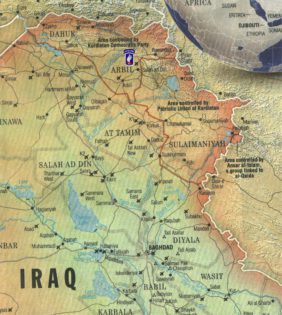

As I have since told everyone about the jump, I was surprised to learn that northern Iraq is more akin to the mountainous, cold, rainy, and vibrant green foliage of Washington State than the image we all hold in our mind of barren sand dunes abundant with camels. Here the mud was pervasive and invasive. The location chosen for our combat jump was a large rice-farm field, which makes sense because airborne drop operations require a big piece of open terrain without obstacles. As luck would have it, it had rained every day of the week before the day we jumped in. The ground was a mud bog.

Eaten alive by the mud bog

Moving through the mire carrying that extreme weight was the hardest physical thing I have ever done in my life. I fell frequently trying to take a step in the mud. I would fall down and be crushed by the weight of my ruck that followed every slip. It took every muscle fiber of my body to get up when I fell, and I fell a lot. It was as if I was in a mortal fight with the ground.

Every step I took, the mud grabbed my boot like a vice and held it as I used every ounce of my physical power to pull that foot up. I was also trying to protect my equipment from the mud. I needed to be able to actually fight at any moment, but I felt I was being eaten alive by the mud, covering every part of my body and equipment, even my night vision goggles and my rifle! Mud on or in any of those vital pieces of gear could render me ineffective in battle, the last thing a leader wants to be.

A soldier without a working rifle as well as the inability to see the enemy is useless. I could not allow myself to be useless, but the mud had other ideas. I wanted to cry in desperation. It was taking what felt like hours to move just a few feet and I needed to move over a quarter mile to get to our platoon’s predesignated linkup spot. An immense amount of fear started to build up in me. Not fear of an enemy force that might be out there but an enormous fear of failing—that I was not going to make it to my linkup site in the required time.

I knew that we had a short amount of time to meet up and then the unit would move out as long as they had a certain number of people, with or without me. I was minutes into my first important responsibility as a platoon leader and I was going to fail. I was going to fail to do my job. I was going to fail to even show up to do my part for the team, to lead them. It did not help my spiraling thoughts of failure that I was alone, in the dark silence.

Then I saw another soldier. Thank God! In training we are required to find someone else or a few others to move with off the DZ. I approached the shadowy figure and whispered, “Who is this?” He responded, “Private First Class Butler, Alpha Company.” Praise the Lord, I thought. Butler was not only from my company—he was one of my guys, a member of my platoon.

I had an overwhelming feeling of relief. It really did not matter who it was, but someone from my platoon was a plus. Nevertheless, I was no longer alone. It did not help me fight the mud monster, but I mentally needed that soldier. Together, Butler and I made it to the assembly area.

The terrain was so hard to traverse that when we tried to move to a dryer location the morning after the jump, the lactic acid had already set into all of my muscles—in my thighs, calves, arms, forearms, hell, even my hands. I could barely move. I ended up spending twenty-five years in the military, endured some very hard workouts, literally exercised all day, completed thirty-mile foot marches, competed in the Best Ranger contest (like the Olympics of the military), but I have never again strained myself or been that sore from physical activity before or after that night and morning after struggling with that muddy morass.

The weight they carried

Unfortunately not all the soldiers were physically or mentally capable of moving the weight they carried through the challenging terrain. Some just quit in place and laid in the mud until the next morning when the sun came up and they could see where dry land was. Others did worse—they laid there complaining of injuries until other soldiers came to drag them out. The next morning we each knew we would be weighed in the eyes of the other soldiers, and we would judge others in return.

This was day one of assessing the value each individual contributed to our new group—our new family. This happens in training, but this was real life, real combat. The stakes were so much higher. I did not understand those who were willing to accept negative judgment from their fellow soldiers.

Everything I had witnessed about peer pressure since middle and high school told me that we should all be trying our damnedest to win the respect of our peers. With the number of soldiers stuck, it proved how difficult those muddy rice fields were.

One of my soldiers physically could not bring himself to move when we were ordered to relocate from the linkup site to another position. He was apparently in so much despair about his inability to carry his gear that he decided that death was preferable to making his body do anything. Two sergeants in my platoon hovered over him yelling at him to get up. He pleaded with them to just leave him.

The sergeants again yelled at him that this was not training and lying in the mud was not an option. My soldier opted for a different solution and attempted to commit suicide. He suddenly jammed the barrel of his rifle into his mouth and was about to pull the trigger.

Luckily he was quickly tackled by the sergeants, who yanked the rifle away from him. Looking back, we all knew his rifle probably would not have fired anyway because it looked like he had stuck the barrel in a pile of feces while trying to hold himself upright in the mud. This soldier had completely disregarded a core value of a soldier—that we have to keep our weapons functional in order to fight.

This was only hours into the war, before we had even encountered the enemy. We took his weapons away, called higher headquarters, put him on a vehicle, and never saw him again.

Suicide or even talk of suicide is no laughing matter. I hope he got the help he needed, but I was also relieved that he was removed from my platoon so quickly.

I joined the platoon as we moved to our follow-on objective.

John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq. He is the author of the book Connected Soldiers: Life, Leadership, and Social Connection in Modern War and coauthor with Liam Collins of the book, Understanding Urban Warfare.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers