“We are a tough people, we used to have war all the time. Fighting is in our DNA.”

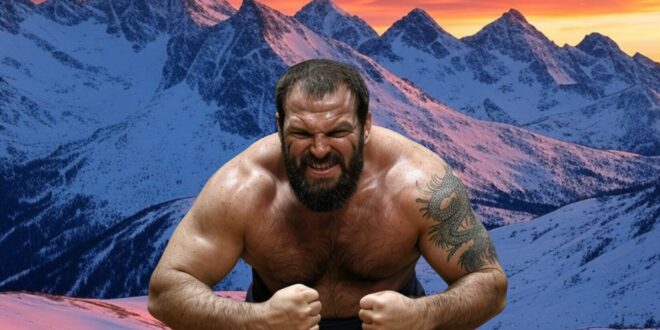

At a major international fighting event this year, all four athletes competing for world championship titles hailed from the Caucasus.

The event, UFC 311, which was held in California on Jan. 18, was scheduled to headline with two fighters from Russia’s Daghestan region as well as a Georgian and an ethnic Armenian.

One of those fighters, bantamweight world champion Merab Dvalishvili, has some theories why fighters from the Caucasus — especially his native Georgia — are so overrepresented in mixed martial arts (MMA).

“We are a tough people, we used to have war all the time,” Dvalishvili, 34, told RFE/RL. “Because we have such nice territory, enemies always used to come to our country and always we used to defend ourselves, our families, our land.” As a result, he says, “fighting is in our DNA.”

Dvalishvili grew up in Georgia’s western Imereti region where many villagers were subsistence farmers. In the wake of Georgia’s 1991-93 civil war, the young Dvalishvili witnessed severe poverty and at times the boy’s own family survived on only cornbread. The family moved to Tbilisi when Dvalishvili was nine.

His journey to the UFC began when he saw a poster on the streets of Tbilisi advertising an MMA fight. Although the contest offered no prize money, he signed up for the event, which introduced him to the thrill of fighting in front of a crowd.

“Every other sport has so many rules and you can’t show yourself,” he says. “Fighting is the best, I was free you know? When I was fighting I felt I was in my best moments.” Dvalishvili suspected he could make a career out of MMA because, he says, “I was so happy when I was doing this.”

Dvalishvili moved to New York in the early 2010s and began working in construction while searching for a training gym that could give him the experience needed to become a well-rounded fighter.

The Georgian’s fighting style showcases his background in judo and sambo — a wrestling-heavy martial art developed for the Red Army — and a willingness to walk relentlessly towards his opponents. That constant forward pressure, combined with seemingly unending stamina earned him the fighting name “the machine.” The Georgian won the bantamweight world title inside the Las Vegas Sphere in September 2024.

In the fight in California, Dvalishvili faced the undefeated Umar Nurmagomedov, a member of a legendary MMA dynasty from Russia’s Daghestan region led by his cousin, Khabib Nurmagomedov, who was famously filmed wrestling with a bear cub as a child. Khabib retired undefeated in 2020 and is regarded by many as the greatest MMA fighter of all time.

Photojournalist Sergey Ponomarev, who has reported on the wrestling culture of Daghestan for The New York Times, points to the climate and landscape of that region as factors in the astonishing number of Daghestani Russians competing at the highest levels of MMA. “It’s because of the mountains and tough conditions to live in the wild,” he told RFE/RL. “They were mostly shepherds in the past.”

So prevalent is the sport in the culture, Ponomarev says, young Daghestanis would “prefer to watch wrestling than football.”

In impoverished mountain villages, wrestling has the advantage of requiring, in its most basic form, only some flat grass and the human body. Fighters in Daghestan frequently utilize their rugged landscape to train, with champions filmed swimming in the region’s icy rivers, and jogging up its mountains for endurance.

Arman Tsarukyan, an ethnic Armenian who was born in Georgia and raised largely in Russia, also competed for a title at the January 18 event against Daghestani Russian Islam Makhachev. While Daghestan’s MMA boom is well established, Armenians say Tsarukyan is sparking an explosion of interest in the sport.

Kim Barsegian, who ran an amateur fight club in Yerevan, says, “with Tsarukyan coming onto the stage I see this great influence and more martial artists, more juniors starting in martial arts.”

Barsegian also points to the harsh climate of the Caucasus as a factor in the grit of fighters from the region, as well as widespread economic hardship. “If you live in very comfortable conditions it won’t make you a good fighter,” he says.

In UFC contender Tsarukyan’s case, however, his upbringing contrasts with the common rags-to-riches story of many MMA fighters. The ethnic Armenian grew up in a wealthy family and puts his own success down to pure discipline. In a recent podcast Tsarukyan recalled a young fighter listing all the expensive training camps he would join if he had the financial freedom of the Armenian. Tsarukyan responded: “If you had how much money I have, you would never come to the gym.”

For Georgian fighter Dvalishvili, who received a heroes welcome when he returned to his home country in September, his growing influence on young Georgians can be seen in training centers across the country. “Every time I fight now, they tell me the gyms are getting more and more full with kids.”

The impact he says, means “more kids avoid smoking cigarettes or hanging out in the streets,” adding, “it’s so easy to do this stuff in Georgia.”

He says that MMA has the power to give purpose to young people at a critical age.

“Sport is the best because they will have a goal to be healthy and to become number one, and all their lives they will be organized and disciplined,” he says, adding, “I’m very proud that I give a good example to young kids.”

– Based on a story by Amos Chapple, RFE/RL

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers