Lincoln‘s Gettysburg address : Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that “all men are created equal”

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live. This we may, in all propriety do. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow, this ground– The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have hallowed it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; while it can never forget what they did here.

It is rather for us, the living, to stand here, we here be dedica-ted to the great task remaining before us — that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here, gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people by the people for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln, Draft of the Gettysburg Address: Nicolay Copy. Transcribed and annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College, Galesburg, Illinois. Available at Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division (Washington, D.C.: American Memory Project, [2000-02]), http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html.

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

Fought over the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg was one of the most crucial battles of the Civil War. The fate of the nation literally hung in the balance that summer of 1863 when General Robert E. Lee, commanding the “Army of Northern Virginia”, led his army north into Maryland and Pennsylvania, bringing the war directly into northern territory. The Union “Army of the Potomac”, commanded by Major General George Gordon Meade, met the Confederate invasion near the Pennsylvania crossroads town of Gettysburg,and what began as a chance encounter quickly turned into a desperate, ferocious battle. Despite initial Confederate successes, the battle turned against Lee on July 3rd, and with few options remaining, he ordered his army to return to Virginia. The Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg, sometimes referred to as the “High Water Mark of the Rebellion” resulted not only in Lee’s retreat to Virginia, but an end to the hopes of the Confederate States of America for independence.

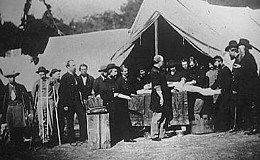

The battle brought devastation to the residents of Gettysburg. Every farm field or garden was a graveyard. Churches, public buildings and even private homes were hospitals, filled with wounded soldiers. The Union medical staff that remained were strained to treat so many wounded scattered about the county. To meet the demand, Camp Letterman General Hospital was established east of Gettysburg where all of the wounded were eventually taken to before transport to permanent hospitals in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington. Union surgeons worked with members of the U.S Sanitary Commission and Christian Commission to treat and care for the over 20,000 injured Union and Confederate soldiers that passed through the hospital’s wards, housed under large tents. By January 1864, the last patients were gone as were the surgeons, guards, nurses, tents and cookhouses. Only a temporary cemetery on the hillside remained as a testament to the courageous battle to save lives that took place at Camp Letterman.

Prominent Gettysburg residents became concerned with the poor condition of soldiers’ graves scattered over the battlefield and at hospital sites, and pleaded with Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin for state support to purchase a portion of the battlefield to be set aside as a final resting place for the defenders of the Union cause. Gettysburg lawyer David Wills was appointed the state agent to coordinate the establishment of the new “Soldiers’ National Cemetery”, which was designed by noted landscape architect William Saunders. Removal of the Union dead to the cemetery began in the fall of 1863, but would not be completed until long after the cemetery grounds were dedicated on November 19, 1863. The dedication ceremony featured orator Edward Everett and included solemn prayers, songs, dirges to honor the men who died at Gettysburg. Yet, it was President Abraham Lincoln who provided the most notable words in his two-minute long address, eulogizing the Union soldiers buried at Gettysburg and reminding those in attendance of their sacrifice for the Union cause, that they should renew their devotion “to the cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion..”

General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate “Army of Northern Virginia”.

Born on January 19, 1807 at “Stratford” in Westmoreland County Virginia, Lee was the son of Anne Hill and Henry Lee, a distinguished cavalry officer during the American Revolution where he gained the nick-name “Light Horse Harry”. Financial problems forced the elder Lee to move his family to a home in Alexandria where Robert attended school and enjoyed outdoor activities along the river. In 1825, the young Lee entered the US Military Academy at West Point. He excelled in his studies and military exercises, graduating second in the class of 1829. Two years later he married Mary Ann Randolph Custis, a direct descendent of Mary Washington and the family moved with Lee’s assignments to the midwest and then Washington. At the outbreak of the War with Mexico, Lee was assigned to the army under General John E. Wool and General Winfield Scott and was wounded at the Battle of Chapultepec. Lee distinguished himself during the war and received several promotions in rank after the war ended. In the decade that followed, he briefly served as superintendent of West Point and accepted a command in the 2nd US Cavalry. It was by chance that Lee was in Washington in 1859 when the violent abolitionist John Brown raided the United States Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Placed in command of Federal troops sent to recapture the arsenal, Lee directed the soldiers who stormed Brown’s last holdout and captured Brown and his fellow conspirators.

Lee declined an offer to command the Union Army at the outbreak of the Civil War and offered his services to his native state. After serving in several administraive and field postions, he was assigned to command the Confederate Army at Richmond, which he named the “Army of Northern Virginia”. Under his command, this army exploited Union mismanagement on numerous battlefields, making Lee one of the most victorious commanders in the Confederacy.

Lee’s army was noted for its cadre of southern commanders who were veterans of numerous, hard-fought battles. Some performed better than in the summer of 1863.

George Gordon Meade, commander of the Union “Army of the Potomac”.

Born in Cadiz, Spain on December 31, 1815, Meade was primarily raised in Philadelphia though his family later moved to the Baltimore area. Meade entered the US Military Academy at West Point in 1831 and graduated 19th in the Class of 1835. Appointed to the 3rd US Artillery and transferred to Florida at the beginning of the Seminole Wars, Meade became ill and was reassigned to the Watertown Arsenal in Massachusetts for administrative duties. Disillusioned with military life, he resigned his commission in 1836 to work for a railroad company as an engineer but re-entered military service in 1842 to provide a stable home for his new wife. His army assignments took him to Texas in 1845 where he was assigned to General Winfield Scott’s Army during the War with Mexico. After the war, Meade returned to Philadelphia where he engineered lighthouses for the Delaware Bay.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Meade offered his services to Pennsylvania and was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in command of a brigade of Pennsylvania regiments. Meade gained a reputation for being short-tempered and obstinate with junior officers and superiors alike, garnering him the nickname “The Old Snapping Turtle”. At the Battle of Glendale on June 30, 1862, he was seriously wounded though refused to leave the field until the loss of blood so weakened him that he could not remain in the saddle.

Meade recovered and was placed in command of the division of “Pennsylvania Reserves”, which he led at the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam, Maryland, and Fredericksburg, Virginia. Subsequently assigned to command the Fifth Army Corps, he participated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, and then marched northward that summer once Lee’s Army had crossed the Potomac River. It was still dark on June 28, 1863, while the army camped near Frederick, Maryland, when a courier arrived at Meade’s tent bearing the news that he was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac. A surprised Meade protested at first but accepted his assignment and rode to army headquarters.

Later that morning, he finished a plan to set the army in motion northward to find Lee. Fortunately, the general had a group of excellent commanders in charge of his army.

Union Commanders at Gettysburg

| General John Buford– The commander of a cavalry division in the Army of the Potomac, John Buford’s troops encountered the head of a Confederate column on June 30th near Gettysburg. It was Buford who decided to stay in the area overnight and wait for the Confederates to return the following day. His choice would set the stage for the Battle of Gettysburg that began the following day, July 1, 1863. General John Reynolds– One of the most highly respected and dynamic Union generals serving in the Army of the Potomac, Reynolds commanded the First Army Corps. Reynolds had reportedly declined an offer to command of the army and recommended fellow Pennsylvanian, George Gordon Meade. Having rushed his infantry to the battlefield on July 1, the general was encouraging his soldiers in a swift counterattack on Confederates in a grove of woods adjacent to the McPherson Farm when he was instantly killed. His loss from was sorely felt throughout the army. Gen. Abner Doubleday– This New York officer took command of the First Corps after the death of its leader, General Reynolds. He deployed his experienced troops on a line west of Seminary Ridge and held the ground until overwhelming numbers forced his depleted regiments to retreat through Gettysburg. After the war he authored Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, his memoir and history of the two great battles that were his last with the Army of the Potomac. General Winfield S. Hancock– Inspiring, bold, and daring, Hancock proved to be an outstanding field commander at Gettysburg. Meade sent Hancock as his representative to Gettysburg on July 1, where he took command of the chaotic situation. The general was everywhere the action was on July 2 and played a prominent role in sending troops to threatened areas. He nearly lost his life while directing a counterattack against Pickett’s Virginians on July 3rd, an injury that would plague him for the rest of his life. General Oliver O. Howard– Commanding the Eleventh Corps, this one-armed general took charge of the field after the death of Reynolds and secured Cemetery Hill as the final Union position for which he later received a congressional thanks. Howard later served in the Atlanta Campaign with General Sherman and in 1867 worked to establish a school for African Americans in Washington, DC, known today as Howard University. General Henry Hunt– In charge of the Union artillery, his disciplined use of Union batteries played a major role in defeating the Confederate battle plans for July 2 and 3. Hunt’s obsession with complete control of the army’s artillery would conflict with infantry commanders at Gettysburg and elsewhere during the war. General Daniel E. Sickles– A colorful politician turned general, Sickles led his Thirds Corps to Gettysburg, determined not to allow the Confederates to hold higher ground. His controversial move forward from Cemetery Ridge on July 2nd resulted in the bloodiest day of fighting, costing the general most of his corps and a leg. Awarded the Medal of Honor for his services at Gettysburg, he sponsored the 1895 legislation that made the battlefield a national military park. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren– Serving as Meade’s Chief of Engineers, Warren was surveying the Union left when he spied Confederate forces moving around the Union left and toward Little Round Top. Realizing its importance, he rushed troops to the hill’s defense, which ultimately saved the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. That evening, the exhausted Warren slept through Meade’s Council of War. He later commanded the Fifth Corps in the Overland Campaign until a conflict with his superiors caused an abrupt end of his field command in 1865. Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain– A school teacher by trade, Chamberlain had risen to the rank of colonel of the 20th Maine Infantry by Gettysburg. His battle tested veterans were pitched into a desperate fight with the 15th Alabama Infantry on July 2nd and despite nearly overwhelming odds, won the day at Little Round Top thanks to their colonel’s stubborn guidance. By war’s end, Chamberlain was a major general and placed in charge of accepting the Confederate surrender parade at Appomattox Court House. Gen. George A. Custer– Long before he would meet his fate at Little Big Horn, Custer, as a newly appointed brigadier general, commanded a brigade of Michigan cavalry regiments. On July 3, 1863, he displayed his dynamic ability to lead men in battle, leading regiment after regiment in desperate charges that eventually won the day in the cavalry battle east of Gettysburg. Lt. Alonzo Cushing– This 22 year-old West Pointer commanded Battery A, 4th United States Artillery. His battery was destroyed in the cannonade prior to Pickett’s Charge though Cushing chose to remain on the field with his lone surviving cannon, which he served against the Confederate infantry attack until shot dead at his post. “Faithful unto death”, his fanactical devotion to duty helped turn the tide at Gettysburg. In 2010, the United States Army approved a request to award him the Congressional Medal of Honor. Dr. Jonathan Letterman– As Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, his skills at organization and support were unequaled. The task of treating countless wounded in and around Gettysburg was left up to his undermanned staff that worked diligently to save thousands of wounded Union and Confederate soldiers. Many convalesced at “Camp Letterman”, the general field hospital east of Gettysburg, before transfer to permanent hospitals in the North. Alexander S. Webb– A newly appointed brigadier general, Webb was placed in command of the “Philadelphia Brigade” during the march to Gettysburg. During Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd, his troops met and threw back the Confederate breakthrough at the Angle. His dynamic leadership made a difference in the Union defense even though he was so new to command that many of the soldiers in the brigade did not know who he was. Lt. Frank A. Haskell– A Union staff officer at Gettysburg, Haskell was a model soldier and disciplinarian who was in the center of the Union line on July 2nd and 3rd where he witnessed most of the climactic events of the battle. He described his experiences in a lengthy letter to his brother that to this day is one of the most descriptive and eloquent battle narratives ever written. Unfortunately, Haskell was killed in battle the following year. |

Confederate Commanders at Gettysburg

| General James Longstreet– The most trusted of Lee’s corps commanders, Longstreet’s troops would bear the brunt of the fighting on July 2nd and July 3rd at Gettysburg. The general was in charge of the main Southern attack on the last day of the battle, even though he did not believe in its success. Much of the Southern controversy about Gettysburg centers around Longstreet’s decisions during the battle, some that would haunt him until the last of his days. Richard S. Ewell– Commanding the Second Corps that was once “Stonewall” Jackson’s, General Ewell was brave in battle and efficient in following orders. At Gettysburg his troops arrived in the right place and attacked at the right time, stampeding Union troops through Gettysburg and capturing hundreds. His decisions later that same day would cause many to wonder what might have occurred had a more aggressive commander been in the general’s boots. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill– Commanding the Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, Hill’s troops opened the battle on July 1, 1863. His troops also fought on July 2, and he sent the better part of two divisions into the grand assault on July 3, also known as “Pickett’s Charge”. Tragically, General Hill did not survive the war. He was killed in Virginia barely a week before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House. General Henry Heth– Marching from Cashtown, Pennsylvania on the morning of July 1, 1863, General Heth’s troops fired the first southern shots of the battle. At the height of the fighting that day, he was struck in the head by a minie ball and knocked senseless though he was fortunate to recover just in time to lead his command during the retreat back to Virginia. After the war he wrote his memoirs, adding that Lee’s army had never been so confident of victory as they were during the Gettysburg Campaign. General John Bell Hood– An aggressive and brave commander who hailed from Kentucky, General Hood commanded a division under General Longstreet. His troops marched 18 miles on July 2nd and then attacked Union troops on Little Round Top and at Devil’s Den. The general was seriously wounded in the arm while leading his troops into battle and though surgeons did not amputate the shattered limb, it would hang useless by his side for the remainder of his life. General George E. Pickett– One of the more flamboyant of Lee’s generals, Pickett worried that his Division of Virginians would fail to see action during the Gettysburg Campaign. As events turned out, his Virginians would reach the “High Water Mark” of the battle and of the Confederacy. His name is forever associated with the third and final day of the battle and the climactic attack against the Union center, known as “Pickett’s Charge”. General J.E.B. Stuart– Bold and dashing, “Jeb” Stuart was the “beau ideal” of southern horsemanship. Commanding the cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia, he directed a successful raid through Maryland and Pennsylvania that ended in controversy when his arrival at Gettysburg came long after the battle had begun, earning him an embarrassing censure from the army commander. Stuart’s horsemen fought a pitched battle three miles east of Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3rd and he was soundly defeated. Gettysburg was one of Stuart’s few defeats during the war. General John B. Gordon– Commanding a Georgia brigade in Ewell’s corps, Gordon was an experienced soldier who had almost lost his life at the Battle of Antietam in 1862. His troops put many of the Union troops to flight on July 1after which he occuppied the town of Gettysburg and was an interested observer at corps headquarters. Gordon survived the conflict and was assigned by General Lee to lead the surrender parade of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House in 1865. After the war, Gordon served several terms as the Governor of Georgia, was an influential leader of The United Confederate Veterans,and in 1904 published his stirring memoir of service, Reminiscences of the Civil War. Col. Edward P. Alexander– In command of a reserve artillery battalion in Longstreet’s Corps, the responsibility of the cannonade prior to Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd was placed on his shoulders. It was Alexander who sent the message to General Pickett begging him to advance while his depleted artillery could still support the charge but was frustrated by misplaced ammunition supplies and the overwhelming Union artillery response. After the war, Alexander wrote extensively about his wartime experiences including his role in the artillery fighting at Gettysburg. Brig. General Lewis Armistead– Commanding a brigade in Pickett’s Division, Armistead led his troops on foot across nearly a mile of open field and into the Union line where he was wounded and captured. A career Army officer before the war, many of his closest army acquaintances were serving the Union cause at Gettysburg. He died in a Union field hospital the following day. Col. William C. Oates– As colonel of the 15th Alabama Infantry, this former lawyer and outspoken newspaperman found himself and his regiment fighting in some of the roughest terrain on the Gettysburg battlefield. In the bitter contest with the 20th Maine Infantry on the boulder-strewn slope of Little Round Top, he would lose almost half of his regiment, including his brother numbered among the slain. Colonel Eppa Hunton– Leading the 8th Virginia Infantry in Garnett’s Brigade, Hunton was painfully wounded during Pickett’s Charge and his regiment lost its flag to the 16th Vermont Infantry. A brigadier general by war’s end, he afterward became a vocal critic of his former division commander and refused to visit the Gettysburg battlefield where he had lost so many of his closest friends. Major General Jubal A. Early – West Point graduate and soldier, lawyer, major of Virginia Volunteers in the War with Mexico and member of the Virginia house of delegates, Early commanded a division of troops in Richard Ewell’s Corps. His troops were the first to enter Gettysburg on June 26, 1863, where he levied a demand for supplies and money from town officials before moving on toward York, Pennsylvania. His hard marching troops swept away the Union Eleventh Corps on July 1 but could not break the defenses of East Cemetery Hill the next day. Gen. James J. Pettigrew– This handsome officer led a North Carolina brigade in the desperate fight on July 1st and a division in Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd. Eleven days later, while in command was the final defensive line of the army’s river crossing on the Potomac River at Williamsport, Pettigrew was mortally wounded by a Union cavalryman, the last general officer lost by Lee in the Gettysburg Campaign. |

In 1864, a group of concerned citizens established the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association whose purpose was to preserve portions of the battlefield as a memorial to the Union Army that fought here. The GBMA transferred their land holdings to the Federal government in 1895, which designated Gettysburg as a National Military Park. A Federally-appointed commission of Civil War veterans oversaw the park’s development as a memorial to both armies by identifying and marking the lines of battle. Administration of the park was transferred to the Department of the Interior, National Park Service in 1933, which continues in its mission to protect, preserve and interpret the Battle of Gettysburg and the Gettysburg Address to park visitors.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers