The Canadian Military and the Canadian Weapons of WWI

Canadian War Museum text and photos

A Dominant Weapon

At first, only the Germans appreciated the power of machine-guns when used on the defence from prepared positions with overlapping fields of fire. All armies would soon learn this lesson, as the machine-gun, perhaps more than any other weapon, drove soldiers from the battlefield and into relatively safe trenches, dug-outs, and fortifications. Overcoming the stalemate created by the dominance of firepower would challenge armies for the rest of the war.

Canadian Machine-Guns

The Canadians went overseas with only four Colt machine-guns in each infantry battalion. The Colt was a good weapon, but it tended to jam after rapid-fire. It was replaced in 1916 with the Vickers, a heavier and more dependable weapon. The German equivalent was the MG 08 Maxim, crewed by five soldiers.

Dividing Heavy and Light Machine-Guns

Heavy machine-guns were later removed from the infantry battalions and grouped into machine-gun units to centralize firepower. They often fired indirect barrages onto enemy lines or fixed positions such as crossroads or supply trenches. Infantry units received growing numbers of the Lewis light machine-gun, which could be carried by a single soldier and fired a 47-round drum magazine. The ammunition was carried by a second member, although in a battle there could be another two or three members of the team to ensure there was sufficient ammunition. The Lewis gun substantially increased the infantry’s firepower during an attack, which could also be supported by the massed fire of heavier weapons.

Huot-Ross Automatic Rifle

Ammunition

The artillery used different shells for different purposes. Shrapnel shells were timed to explode over enemy lines, sending down hundreds of tiny metal balls. This rain of metal, which exploded outward in a shotgun blast, caused terrible injuries to soldiers caught in the open.

Trenches helped to protect against shrapnel, but even trenches were vulnerable to high explosive shells that burst like dynamite, leaving large craters in the ground and killing and maiming anyone caught in the blast. The explosive charge also shattered the shell creating jagged shell splinters. Gunners used high explosive shells to collapse trenches and lightly protected shelters, but only the larger siege guns could destroy deeper enemy shelters or prepared defences.

German Howitzer

Mortars

Mortars were simple but effective weapons widely used in siege warfare for more than 400 years. Essentially metal tubes with bases, mortars fired shells in a high arcing trajectory that plummeted down into the enemy lines or fortifications. First World War armies used many calibres and types of mortars, from heavy siege mortars to lighter, so-called “infantry mortars” that could be taken apart and carried forward by small groups of gunners.

The Gunner’s War

The number of artillery guns expanded enormously during the war. Larger-calibre guns, and more of them, allowed the Allied armies to fire a nearly limitless supply of shells by the midpoint of the war.

As the Allied gunners embraced scientific principles that accounted for weather and atmospheric conditions, as well as new tactics, they were better able to locate, target, and destroy German gun batteries, which suffered increasing shortages of shells and guns throughout the war from the naval blockade. By 1918, Allied gunners overpowered the German guns, resulting in heavier bombardments and more devastating creeping barrages to support the infantry when they were ordered to close with the enemy. (Above: Huot-Ross Automatic Rifle)

The static battlefield on the Western Front led to the development of new and more effective weapons, and the improvement of old ones.

The Trench Deadlock

The enormous firepower of machine-guns, quick-firing artillery, and modern rifles forced the infantry to dig into the ground. The first shallow, temporary ditches gradually expanded into deeper trench systems. Most attacks against these trenches ended in failure. New weapons were introduced throughout the war to help break the deadlock.

Personal Weapons and Small-arms

At the start of the war, most soldiers carried only a rifle and a bayonet, and most soldiers within the same small unit were similarly armed. As the war progressed, armies used a wider variety of weapons to better equip their troops for trench fighting and attacks across No Man’s Land, including grenades, rifle grenades, mortars, and several types of machine-guns.

Small units, of eight to 30 soldiers, came to rely on a balance of rifles, machine-guns, and other weapons. Training for raids and attacks emphasized how firepower, movement, and innovation could be used to go through, or around, enemy strong points.

Raiding with Knives and Clubs

Unofficial weapons, including knives, hand-made clubs, and small catapults were particularly useful in raids. From late 1915, the Canadians engaged in a series of hit-and-run assaults on enemy trenches. These raids were meant to kill the enemy, to gather intelligence, and to win control of No Man’s Land. The Canadians soon acquired a reputation as fierce raiders, despite the heavy casualties they often incurred.

Innovation Outside the Trenches

In addition to the development of better and more varied weapons and tools for the infantry and engineers, the war also saw the use of poison gas, underground mining, airplanes, airships, submarines, and tanks. Many of the war’s most fearsome inventions, including poison gas and tanks, were intended specifically to aid armies on the attack and by 1917-1918, were being used effectively to break into and out of enemy trench lines.

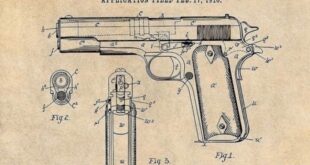

Revolver

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers