The CIA’s Covert Operations in Laos during the Vietnam War.

Jack Jolis served as a case officer in the CIA, operating the Rascal program out of Lima Site-20 Alternate, or Long Tieng, for much of 1970. These are his recollections, in an interview with British writer, Peter Alan Lloyd

PL. Jack, how did you end up to Laos?

JJ. I enlisted in the US Army after leaving Cornell University in 1967 and after a year of basic, infantry, officer and intel training, and after my 1-year tour of duty in Vietnam, I left the US Army as a 1st. Lt, in 1969 and joined the CIA as a “Career Trainee”.

Support aircraft for ground operations like the Rascals: F-100Ds flying over South Vietnam in 1966. (USAF)

I completed the Agency’s 6-month training program and became a case officer in the CIA’s “Clandestine Service”, assigned to the Africa Division. I was slated to be assigned to Congo-Kinshasa (then-Zaire) as a Defense Attaché (and to be “promoted” to Army captain as my “cover”), but thanks to a girlfriend I had at the time who was a senior (senior in position rather than age) secretary in the South-East Asia Division, I learned that a vacancy had opened up in our 55-man paramilitary operation with the Meo/Hmong in northern Laos, owing to the wounding of one of the case officers there, a certain Dick M.

I volunteered for the gig, and thanks to a good word in the ear of the SEA boss from my friend, his Secretary, plus the fact that I was a baggage-less bachelor fresh from Vietnam, I was given the nod.

PL. Were you based in Udorn Thani or Long Tieng?

JJ. I had an assigned bunk in the rather Spartan “barracks” both in the Agency’s hooch in Udorn-Thani AFB, and one up in the communal case officers’ hooch up in Long Tieng. I also had the use of a case officer “safe house” in Vientiane, but I only used that for the occasional “overnight”.

All in all I spent about 90% of my time in Laos living in and operating out of Long Tieng.

PL. What was your radio call sign, if you had one?

JJ. I did have a radio call sign up there in “SKY/CAS” (“SKY” was the Agency code name for the whole northern Laos operation itself — named by famed case officer Jerry Daniels (“HOG”), for his beloved Montana “Big Sky Country”, and “CAS” was simply the code-name for the Agency, and stood for “Controlled American Source”).

My radio call sign was “Hippie”.

PL. How did you get it?

JJ. It was given to me by our second in command, Bob “Burr” Smith, a legendary D-Day 101st Airborne “Band of Brothers” veteran who was now with the Agency. He had a shaved head and was known as “Mr. Clean”, or just “Clean”, and he decided I should be radio-called “Hippie” because I wore my hair perhaps 1 millimeter longer than the rest of them.

As a newcomer, given Clean’s fearsome reputation, including roaring around the Landing Sites of northern Laos armed with his ubiquitous M-79 grenade launcher, which he wielded like some kind of sawed-off shotgun, I wasn’t going to argue.

I also got it perhaps because I had quickly replaced some of their ubiquitous country music on the tape deck in the “officer’s club” (a small wooden cabin perched atop a giant boulder which contained a grenade-hollowed-out grotto in which resided the big dyspeptic bear which had been given to us by the King of Laos) with tapes by Creedence Clearwater Revival, Steppenwolf, and the Steve Miller Band which I’d bought from the Udorn PX

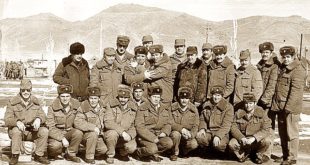

Burr Smith, ‘Mr Clean’ with the head of the Thai Army and Vang Pao, to his left, overlooking Long Tieng air base.

PL. What was your role at Long Tieng?

JJ. My job was to create and run something which I named the ”Rascal” program, which was an idea that had been cooked up by case officers Dick M. and Bob W., but Dick M. had gotten all shot up and was now in a hospital in Japan somewhere and Bob W.’s tour was just coming to an end when I got there, so I was assigned to develop and run what became the Rascal program, something I proceeded to do with the blessing and assistance of Vang Pao’s Chief of Intelligence, (“S-2″), a cherubic-looking and extremely convivial French-speaking Major Hang Sao, and a trusty interpreter/”gofer” that Hang assigned to me, the amiable Corporal Vang Kou.

PL. What did the Rascal program entail?

JJ. Rascal consisted of me and Vang recruiting, training, and then, via Air America helicopters and STOL Porter Pilatuses, inserting and eventually extracting 2-4-man teams of Hmongs who would be disguised as innocuous civilians and whose job it was to wander off into the mountainous jungle in north-eastern Laos and find concentrations of North Vietnamese troops.

Once they found those concentrations of NVA, they were to pass through them, but, crucially, leaving behind them, on the ground, radio beacon devices which we had fiendishly crafted to look like indigenous rocks, or twigs, or even leaves, which they would “switch on” and drop off as close to enemy troop concentrations, or supply depots, as they could.

Also, they could drop and jettison these beacons un-switched-on, on the spot, if they thought they were in danger of being detained and searched.

PL. What happened then?

JJ. After dropping off these devices they would “didi-mau” (Viet for de-ass the area) quick as they could to a pre-arranged extraction point at a pre-arranged time, and I would come in (“behind enemy lines” you might say, although there weren’t any properly-understood “lines” of any kind up there) with one of the aforementioned Air America Hueys or Porters and collect their very-much-relieved asses.

More CIA ingenuity: Transmitters dropped on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, made to resemble faeces.

Once airborne, and (it was hoped) above the 12,000 feet elevation beyond which NVA fire could not reach us, I would call in the USAF, either the F-4 Phantoms and/or C-47 “Spooky” gunships out of Udorn, or else the B-52s (“Arc Light” – the B-52s were known as “Arc Light” over Laos, but by the rather better-known “Rolling Thunder” over Vietnam), which were based in Guam but which were constantly on station, flying over the skies of Laos and South Vietnam, and connect them to the beacon on the ground, and then get the hell out of the way, ahead of the resulting shit-shower.

A Super Sabre aircraft fires a salvo of 2.75-inch rockets against a North Vietnamese Army position in 1967. (USAF).

PL. Can you say a little more about how you honed in on the beacon signal?

JJ. The way it would work was as follows: Each decoy/beacon came with its own frequency info on a separate bit of paper from the Techs in Udorn, and this info I’d keep with me when I gave the device to the Rascal team. (In fact, once we got the Rascal op up and going pretty well, I’d sometimes give the teams 2 or 3 devices to drop, depending on where they were going and what we hoped we’d find).

Anyway, after about 12 hours, or after about the most optimistic amount of time that I judged that they might have needed to encounter a target, I’d start flying around over the “target area” — quite high, above the range of the NVA’s most powerful DShK guns, searching for the beacon signal. I would by this time have passed on the frequency info to the Air America pilot, and he’d be doing the monitoring on his headphones.

Sometimes this took quite a while, and often we had to turn back, having picked up no beacon signal, as the aircraft’s fuel was low, or it was more urgently needed elsewhere, in which case I’d go back to Long Tieng and organize another AA Huey or Porter, and start again. And so on until eventually I/we’d pick up the beacon.

PL. How did you know it was safe to land?

JJ. We’d only go down if the Rascals had deployed a “safe to land” signal, which was just an innocuous bit of cloth of some kind (it had to be innocuous in case they were stopped and searched).

At that point, we’d go in and scarf ‘em up. Bim bim bim. In like Flynn. And only then, when we were airborne and on the way back to safety, did I have the AA pilot relay the coordinates of the beacon to the nearest USAF FAC (finally, the “Raven”), who was usually also airborne somewhere, but occasionally was back at Long Tieng. And it was the Raven who brought in the Air Force, PDQ.

PL. Were you able to watch the air strikes or were you back in Long Tieng by the time they went in?

JJ. We’d usually be on the way back to base, although if we’d hit a particularly big ammo dump, we could see some “fireworks” from miles away, or in the case of a large fuel depot, there would be some very high black smoke. Other than that, I and the Rascal team could not actually see the result with our own eyes, but I always got the results from USAF “after-action” and “bomb damage” reports, which were relayed to me in Long Tieng sometimes a day or two later. And I’d tell my guys.

PL. How did you minimise the risk of attracting enemy attention when landing your Rascal teams?

JJ. It was one of the calculated risks we took. We came in fast and low, and did not, to put it mildly, hang about.

We’d also try to put them in someplace as far away from where we suspected there were enemy concentrations as we tactically could – I mean, we hardly wanted to drop them into a “hot” situation! But at the same time, we dropped them as close as we prudently could so they wouldn’t get too tired or lost on their way in.

The average Rascal operation lasted about 24-48 hours, from insertion to extraction, and we didn’t want to needlessly add to their stress and exertions right at the beginning.

PL. Were you shot at much on your way in or out?

JJ. I don’t remember ever getting shot at during an insertion phase, but occasionally we did during an extraction. Remember, although we tried to pick our pre-arranged extraction points (and alternate extraction points) in as “safe” spots as we could find, we were still technically picking them up behind enemy lines – in “Injun Country”.

Needless to say, on those occasions that we did take fire when picking them up, I did not waste much time in firing back – partly because I couldn’t take the time to try to find the fuckers who were firing at us, (and probably wouldn’t have been able to if I’d tried), but more importantly, by far our number one priority was to get the hell out of there as bleeding quickly as possible.

PL. What kind of ground fire do you remember taking?

JJ. It was almost exclusively AK fire, although I remember once when an RPG went by and exploded into a bunch of trees next to the LZ where we’d landed the Huey. Quite a motivating experience.

I’d long since become familiar with being on the receiving end of B-40s, but familiarity never bred complacency, I can assure you.

PL. Can you say any more about the disguised transmitters used in Rascal operations?

JJ. Our “Techs” made ‘em in Udorn. They were very realistic rubberized rocks, twigs and leaves with tiny little black on/off switches on them which, when dropped somewhere, became immediately “invisible” — the only way of telling something might be fishy was if you picked one up, as they weighed considerably more than they “should” have. Their surprisingly strong radio signals could last for several days and radiated out for enough kilometers to suit our needs.

PL. How many Rascal teams were you running?

JJ. All in all I organized and ran about 6 or 7 Rascal teams.

During my time there we ran a total of about 30 operations, and every one of these operations proved to be successful, in that in every case they resulted in some sort of “secondary explosions” or other, and some of those secondary explosions were pretty spectacular — such as when we’d get a direct hit on an ammo or fuel depot.

A 1966 reconnaissance photo of Viet Cong trucks destroyed on the Ho Ch Minh Trail. They were hit in a US air strike, the surrounding trees having been burned in the resulting fire. (USAF)

PL. Encouraged by your successes, did you ever feel over-confident and want the Rascals out there for days, with bags of beacons

JJ. No, I was rather constantly fretting over their vulnerability – in retrospect, probably needlessly so. But also, I wanted to keep their missions as simple and un-complex as possible. If ever the KISS Principle was called for, it was then.

PL. Did they take weapons or any form of communications, for use in emergencies?

JJ. No. I didn’t want anything on them to indicate they were anything other than jungle-wandering Hmong. They carried no weapons, radios or flares, so had they got into trouble they would have had it really, with no hope of rescue.

These guys were incredibly brave, although they could rationalize it to themselves as sort of “swimming around” amongst Their Own people, in Their Own mountains. To them, in a sense, they weren’t going “behind enemy lines”, but were rather inspecting their property with a view to ejecting alien interlopers.

One of the great successes that we Americans achieved up there was that we somehow managed to never come across to the Hmong as “alien interlopers” — they really did see us as “foreign friends”, who just happened to share a common enemy – the Viets.

PL. Where did the Rascal Program operate?

JJ. When I got there we had just retaken the PDJ (Plain of Jars), so mostly the enemy was in the rather large area east of it, and west of North Vietnam. I remember on several occasions the AA pilot telling me that we were “technically” flying over North Vietnam, (which always added a little frisson to the proceedings)

PL. Was the Rascal operation over so quickly that the NVA didn’t get wind of it? Surely they must have suspected some too-clever surveillance was afoot but maybe they couldn’t work out what it was?

JJ. I think the NVA just figured that our uncannily accurate air strikes were due to some sort of diabolical technological wizardry on the part of the USAF, of which their propaganda was always, in any case, hyperbolically jabbering – and conversely I think that the arrogant NVA had such a low regard for the Hmong that it would never cross their minds that these little people who roamed around the mountains could be capable of calling in such high-tech hellfire from the sky on their asses.

PL. Did working with the Hmong throw up any interesting or unusual cultural issues which you had to manage as part of running a successful operation?

JJ. Our Hmong were not only illiterate, but they also had no idea about such “technical” notions as north, south, east or west, so obviously compasses were out during our training.

I solved that problem by using “China” for N, “Vietnam” for E, “Vientiane” for S., and “Thai/Karen” for W. with them — concepts which they did understand. Sort of….

Also, their religion was/is an amorphous sort of animism which is constructed around a vaguely malevolent gallimaufry of “spirits”, or “Phi’s” — some “good” but mostly “bad”. And at the beginning of the Rascal program, our operations were considerably handicapped by the unfortunate tendency of one or the other of these guys to wake up on any given day having been “told” by one or the other of the “bad Phis” in the night that the next day would be an inauspicious one and therefore they could not embark on any walkabout behind enemy lines just then, but would have to postpone their participation until such time as the “bad Phi” gave him the green light.

At first I thought they were just malingering, but Vang Kou (and his boss, my friend the S-2 Hang Sau) quickly assured me that, no, this was a sincere fear on their parts of what the “spirits” had “told” them.

A Hmong Shaman chants in front of an altar using a hoop rattle while sitting on his “horse,” a wooden bench, to drive away spirits responsible for sickness. The black veil covering his face indicates that he is in a trance. (Terry Wofford, Wofford Collection, wisc.edu)

Complaining about it in the “officer’s club” above the bear cage one night, my problem was miraculously solved by our one doctor assigned to SKY, a USAF captain, who went back to his hooch and re-emerged with a large jar of multicolored pills, sort of like un-shiny Smarties, which he told me were placebos.

The next time one of my chaps told me regretfully that he’d been visited by a “bad Phi” in the night, I asked him “Which Phi?” And when he’d say, for example, “The wind Phi”, I’d say, “Aha! In Washington the wizard doctors have discovered special pills precisely against the wind Phi — here, take this blue one!” And if it was the “rain Phi”, then he’d get a red pill. And so on. These guys had a touching respect for the Americans’ Medicine, and the whole wheeze worked like a charm, pardon the pun — all I had to do was to remember which colored pill was for which bad Phi.

PL. Can you recall who is shown on the above photograph?

JJ. I’ve got precious few pictures from my time up there – as you’ll appreciate, amateur photography was not encouraged, but in this one I remember I was aged 24, and it was taken in 1970 in Long Tieng.

The rather jaunty fellow on the right of the photo is my translator/”gofer” Vang Kou, and if he looks cheerful it’s because he didn’t have to go on missions, like the other, somewhat more abashed, Rascal chappies in the photo did.

I’m ashamed to say that I don’t remember the individual names of those 3 Rascals in the picture, or which particular team they were, but looking at them now I vividly remember them and what an outstanding bunch of blokes they were.

Although in the picture they’re wearing the green fatigues we gave them for training purposes, when they went out on a Rascal mission they were dressed in black Hmong civilian garb. I also remember that they were all members of the same “sub-clan” – sort of extended family.

PL. What’s the insignia on your hat in the photo?

JJ. I replaced my US Army 1LT silver bar with the ARVN 1LT insignia, just for the hell of it. That was the only insignia I wore, other than a small Royal Lao flag pin.

I’d been given the ARVN 1LT insignia by a “counterpart” in Vietnam. It was really just a silly affectation on my part, as any Hmong that would have recognized it for what it was would have probably reacted negatively – they hated all Vietnamese, North, South, it didn’t matter. But as far as I could tell, none ever recognized it – certainly no one ever made any adverse comment….

A Search and Rescue Helicopter lands in the jungle during the Vietnam War.

PL. Your time in Long Tieng in 1970 coincided with some material advances by the NVA in Laos. At any point did people around you think this was an unwinnable war?

JJ. Not really.

We were all pretty much “True Believers” up there – double and even triple volunteers – we’d all previously volunteered for Vietnam, and some went back to Korea and even, while I was there, there were at least 2 “Ranger” volunteers from Normandy ’44. And, regardless of what we thought of the regular Lao military (or even the abilities of our considerably more effective and plucky, but still limited, Hmong “army”), we were pretty comprehensively (if not arrogantly) confident in our own abilities as well as those of our mates in Air America and the USAF. But I’ve got to tell you two things which might strike outsiders as odd:

Firstly, we didn’t concern ourselves much with anything like a “big picture”. Even the “South Laos” war being fought by our fellow Agency and AA guys just a few hundred klicks from us might just as well not have existed. We concentrated 100%, to the exclusion of practically everything else, on the immediate job to hand… which in any case was more than enough for us to handle – remember, there were never any more than a grand total of 55 Agency case officers in all of Military Region II (which included Long Tieng), at any given time..

In short, we had total “tunnel vision”, and for all intents and purposes, the rest of the world didn’t exist for us.

And secondly, although our individual politics almost certainly began with what you might, today, describe as “center-right” and went on over to every shade of (respectable) anti-leftism, we never actively considered, or, Heaven forbid, actually discussed politics qua politics.

You could distill our collective “SKY/CAS” attitudes into the following basic precepts:

1/ We disdained pretty much all forms of Authority and did our best to either counter it, or, better yet, ignore it.

2/ We respected but nevertheless cordially hated the NVA in particular, and we hated (leaving off the respect) the Soviet Union, Red China, and communism in general.

3/ We had few illusions about any long-term or stable “military victory” for our side – after all, there were 55 of us facing some 50,000 NVA right there where we were sitting, and absolutely no political prospect to rectify that imbalance – but we vaguely hoped for and even expected some kind of messy but nevertheless “satisfactory” outcome – something perhaps along the lines of a “Korean War” wind-up.

But in no way and at no time did we allow any of these theoretical musings interfere with our single-minded dedication to what we were doing, at that time, in that place. So while we faced tactical setbacks and even defeats on a daily basis, we were always hopeful, if only vaguely so, about “the Big Picture” — insofar as we ever even thought about it.

PL. Were you ever decorated or otherwise recognised for running what must surely be one of the most cost-effective operations of the war, given you suffered no losses, used so few operatives and always hit something worth blowing up?

JJ. No. None of us were, at least as far as I knew, anyway. (Funnily enough, I got several medals for my service in Vietnam, including the Bronze Star, for – and trust me, I’m not being falsely modest, here – doing stuff of considerably less consequence than what we accomplished in northern Laos).

But one of the main things when you join the Agency — and certainly when you go into the Agency’s Clandestine Service — is that you know from the get-go that, although you will most assuredly be blamed if things go wrong, you will never be rewarded or recognized if things go right. They even test you specifically on this, as part of their batteries of shrink tests they put you through right at the beginning, to see whether you’re psychologically OK with this sort of dubious “arrangement”.

Having said that, the Agency does have something they call “The Intelligence Medal”, but that’s I believe something they give you for “long and distinguished” service. In other words, pretty much a gong in recognition of one’s skill in climbing and staying atop greasy poles. And even then, the whole thing has more than a whiff of Monty Python about it — they give it to you at a ceremony in the auditorium in Langley, at which your family can attend, but no photographs are allowed, and (the best part), they take the medal back from you when the ceremony is over. Strewth.

Anyway, it should go without saying that not only did I never get any Intelligence Medal, I’m pretty sure I don’t personally know anyone that did.

The only other Agency “decoration” I can think of is if you’re KIA, in which case they put a big gold star with your name on it up on the wall — the “Wall of Honor” — in the entrance foyer at Langley HQs. I did know one or two of the names up there….

PL. Were the Air America pilots ever decorated?

JJ. No. The Air America jocks also didn’t get any medals or decorations, but at least they got damn well paid — and while we, the “customer” never begrudged them a penny of what they bloody well earned, it was considerably more than we were making on our government bureaucrat’s salaries.

Under the pseudonym of P.N. Gwynne Jack wrote two well-received comic adventure/espionage novels, “Firmly By The Tail” and “Pushkin Shove”, the former taking place in Africa and the latter in Europe. He also self-published a fictionalized version of his Vietnam and Laos wartime experiences called “Imperialist Warmonger Pig”. Although now out of print, second-hand copies of the first two can be found online, and reprinted copies of all three can be obtained through direct arrangements with the author at [email protected]

Our new film, M.I.A. A Greater Evil. Set in the jungles of Laos and Vietnam, the film deals with the possible fate of US servicemen left behind after the US pulled out of the Vietnam War.

VISIT PETER ALAN LLOYD AT FACEBOOK

See the trailer for our new film, M.I.A. A Greater Evil.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers