of David Crockett

By 1835, Antonio López de Santa Anna had established himself as a dictator in Mexico. Among Anglo-American colonists and Tejanos alike, the call for Texas independence grew louder. On March 2, 1836, a delegation at Washington-on-the-Brazos adopted the Texas Declaration of Independence, and thus was born the Republic of Texas.

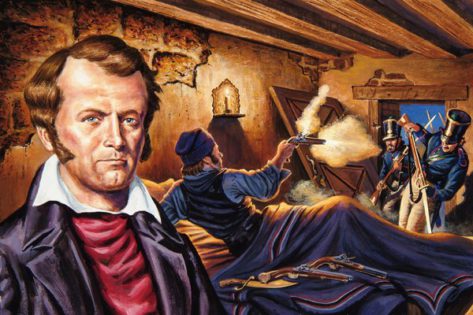

Santa Anna had brought his army to Texas to put down the rebellion, and events followed in quick succession. At the time the Declaration was issued, many Texans were fleeing their homes eastward ahead of Santa Anna’s army, in what became known as the Runaway Scrape. The Alamo fell to Santa Anna on March 6, and over 300 unarmed Texan prisoners were massacred at Goliad on March 27. Sam Houston’s revolutionary army was also retreating eastward as Santa Anna drove for the coast to capture Texas seaports. On April 21, the Texan army took a stand in the bayou country near present-day Houston at a site called San Jacinto. They attacked Santa Anna’s army while it was sleeping, and, in a battle lasting only 18 minutes, routed the Mexican army and captured Santa Anna.

Many Texans favored immediate annexation by the United States. However, the proposals went nowhere, because of the risk of continued war with Mexico and Texas’ shaky financial status. Even after San Jacinto, Mexico refused to recognize Texas’s independence and continued to raid the Texas border. The new government had neither money nor credit, and no governmental structures were in place. Rebuffed by the United States, Texans went about the business of slowly forming a stable government and nation. Despite many difficulties and continued fighting both with Mexico and with Indian tribes, the Texas frontier continued to attract thousands of settlers each year.

In 1841, Santa Anna again became president of Mexico and renewed hostilities with Texas. By this time, sympathy for the Texan cause had grown in the United States, and in 1845, annexation was at last approved. Hostilities with Mexico and the Indians reached a settlement, and Texas was admitted as a state on December 29, 1845. The Republic of Texas, after nine years, eleven months, and seventeen days, was no more.

Texas Independence Day on March 2

Joseph Milton Nance

REPUBLIC OF TEXAS. In the fall of 1835 many Texans, both Anglo-American colonists and Tejanos, concluded that liberalism and republicanism in Mexico, as reflected in its Constitution of 1824, were dead. The dictatorship of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, supported by rich landowners, had seized control of the governments and subverted the constitution. As dissension and discord mounted in Texas, both on the military front and at the seat of the provisional government of the Consultation at San Felipe, the colonists agreed that another popular assembly was needed to chart a course of action. On December 10, 1835, the General Council of the provisional government issued a call for an election on February 1, 1836, to choose forty-four delegates to assemble on March 1 at Washington-on-the-Brazos. These delegates represented the seventeen Texas municipalities and the small settlement at Pecan Point on the Red River. The idea of independence from Mexico was growing. The Consultation sent Branch T. Archer, William H. Wharton, and Stephen F. Austin to the United States to solicit men, money, supplies, and sympathy for the Texas cause. At New Orleans, in early January of 1836, the agents found enthusiastic support, but advised that aid would not be forthcoming so long as Texans squabbled over whether to sustain the Mexican constitution.

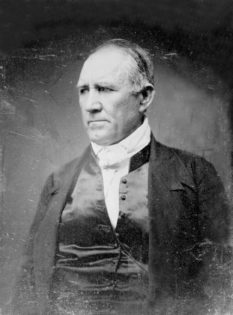

The convention held at Washington-on-the-Brazos on March 1, 1836, was quite different from the Consultation. Forty-one delegates were present at the opening session, and fifty-nine individuals attended the convention at some time. Two delegates (José Francisco Ruiz and José Antonio Navarro of Bexar) were native Texans, and one (Lorenzo de Zavala) had been born in Mexico. Only ten of the delegates had been in Texas by 1836. A majority were from other places-primarily from the United States, but also from Europe. Two-thirds of the delegates were not yet forty years old. Several had broad political experience. Samuel P. Carson of Pecan Point and Robert Potter of Nacogdoches had served, respectively, in the North Carolina legislature and in the United States House of Representatives. Richard Ellis, representing the Red River district and president of the convention, and Martin Parmer of San Augustine, had participated in constitutional conventions in Alabama (1819) and Missouri (1821), respectively. Sam Houston, a former United States congressman and governor of Tennessee, was a close friend of United States president Andrew Jackson. Houston was chosen commander in chief of the revolutionary army and left the convention early to take charge of the forces gathering at Gonzales. He had control of all troops in the field-militia, volunteers, and regular army enlistees. The convention delegates knew they must declare independence-or submit to Mexican authority. If they chose independence they had to draft a constitution for a new nation, establish a strong provisional government, and prepare to combat the Mexican armies invading Texas.

On March 1 George C. Childress, who had recently visited President Jackson in Tennessee, presented a resolution calling for independence. At its adoption, the chairman of the convention appointed Childress to head a committee of five to draft a declaration of independence. When the committee met that evening, Childress drew from his pocket a statement he had brought from Tennessee that followed the outline and main features of the United States Declaration of Independence. The next day, March 2, the delegates unanimously adopted Childress’s suggestion for independence. Ultimately fifty-eight members signed the document. Thus was born the Republic of Texas.

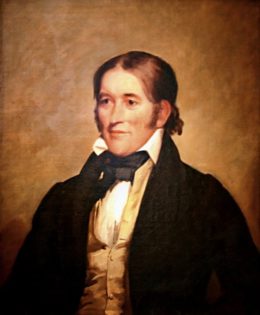

The Myth and Legend

of David Crockett

Dr. R. Bruce Winders, Former Alamo Director of History and Curator

David Crockett easily remains one of the most popular figures associated with the Alamo. So important is he to the story that a persistent misconception contends that he was the commander of a contingent known as the “Tennessee Mounted Volunteers” who followed him from their home state to Texas. In reality, Crockett came to Texas accompanied by a few friends and a nephew[1], reportedly vowing to be content to serve Texas in the role of a “high private.” In early January 1836 Crockett, enlisted as a private in the Volunteer Auxiliary Corps for a term of six months, prepared to march off to Matamoros as part of Johnson’s and Grant’s ill-fated expedition. It was clear, however, that he hoped to revive his political fortunes, telling his family that he hoped to be elected a delegate to serve at the upcoming constitutional convention to be held at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Failing in that endeavor due to questions over his eligibility, he was sent off to San Antonio de Béxar. Arriving there around February 8, Crockett became a member of Captain William B. Harrison’s volunteer company. However, his status as a former Congressman and colonel of Tennessee militia guaranteed that his fellow volunteers accorded him a special place in the garrison.

Documents Regarding David Crockett in Texas

January 14, 1836: Crockett signed an oath at Nacogdoches to serve as a Volunteer Auxiliary Corps for a term of six months.

“I do solemnly swear that I will bear true allegiance to the Provisional Government of Texas, or any future republican Government that hereafter may be declared, and that I will serve her honestly and faithfully against all her enemies and opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the Governor of Texas, the orders and decrees of the present and future authorities and the orders of the officers appointed over me according to the rules and regulations for the government of Texas. ‘So help me God.’

Colonized in the eighteenth century by the Spanish, the Republic of Texas declared its independence from Mexico on March 2, 1836. The Republic of Texas was not recognized by the United States until a year later in 1837.

The question of incorporating Texas into the United States was an issue that strained U.S. relations with Mexico during the 1840s. Although Texas was annexed by the United States in late December 1845, the formal transfer ceremony occurred on February 19, 1846, thus officially ending diplomatic relations between the Republic of Texas and the United States.

On August 23, 1843, Mexican Foreign Minister Bocanegra informed U.S. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Mexico, Waddy Thompson, that U.S. annexation of Texas would be grounds for war. On March 1, 1845, U.S. President John Tyler signed a congressional joint resolution favoring the annexation of Texas. On March 4, 1845, U.S. President James Knox Polk noted his approval of the “reunion” of the Republic of Texas with the United States in his inaugural address. In response, the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs informed U.S. Minister to Mexico, Wilson Shannon, on March 28, 1845, that Mexico was severing diplomatic relations with the United States. In December 1845 Texas was admitted to the union as the twenty-eighth state. In April 1846, Mexican troops attacked what they perceived to be invading U.S. forces that had occupied territory claimed by both Mexico and the United States, and on May 13, the U.S. Congress declared war against Mexico.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers