By Liam Collins and John Spencer

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from the book “Understanding Urban Warfare” published by Howgate Publishing and available for purchase at Amazon here. The excerpt is an edited conversation John Spencer had with Lt. Gen. James Rainey about the 2004 Second Battle of Fallujah Iraq. The views expressed by General Rainey are his and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

The United States invaded Iraq in March 2003 and quickly overthrew Saddam Hussein and his Ba’ath Party government. Some mistakenly believed that the war was over when President George W. Bush declared that “Major combat operations in Iraq have ended,” while standing beneath the “Mission Accomplished” banner onboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, but a Sunni insurgency was already simmering. The insurgent stronghold was located within the “Sunni Triangle,” a densely populated region in central Iraq inhabited largely by Sunni Muslims. The triangles’ points included the cities of Baghdad, Tikrit, and Ramadi.

The city of Fallujah, located between the cities of Baghdad and Ramadi, became an insurgent hotbed and served as the base of operations for al Qaeda affiliate Jamat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad. Fallujah rests on the banks of the Euphrates River. It is a densely populated, industrial city that grew as a way station along silk road branches that connected Baghdad to major population centers such as Aleppo, Syria. In 2004 Fallujah had an estimated population of 250,000 to 300,000 residents.

On March 31, 2004, insurgents ambushed, killed, and subsequently burned four American security contractors in Fallujah. Two of the contractors’ bodies were hung from the ramparts of a bridge on the outskirts of the city. Images of the hanging bodies were televised and broadcast world-wide. In response, Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, the commander of the coalition forces in Iraq, ordered the I Marine Expeditionary Force to launch Operation Vigilant Resolve into Fallujah to deny its use as an insurgent sanctuary and to arrest those responsible for the killing of the contractors.

U.S. Marine Regimental Combat Team 1 (RCT-1) initiated the assault on April 5. The attack was slow due to the size of the enemy, estimated to be about 2,000 insurgents; the complexity of fighting in a densely populated large city; a lack of armor capability; and a complete loss of their Iraqi paramilitary support. On April 9, four days after the operation’s start, General John Abizaid, the commander of U.S. Central Command, ordered Sanchez to suspend the operation. Pressure from the Iraqi governing council and the Coalition Provisional Authority forced the Marines to prematurely halt the operation. International criticism of the mission sparked by footage of what was dubbed as excessive force also contributed.

On April 25, a locally raised Iraqi military force called the Fallujah Brigade under the command of Major General Jassim Mohammed Saleh assumed control of Fallujah. American forces withdrew to the outskirts of the city and the Marines retained a loose cordon around the city, consisting mainly of checkpoints. In total, 27 American servicemembers were killed and more than 90 wounded during the first battle of Fallujah.

Elsewhere in Iraq, violence escalated as Shia leader Moqtada al-Sadr engaged in a political battle with the new Iraqi government. Al-Sadr loyalists in his armed militia known as Jaish al-Mahdi (the Mahdi Army) eventually took to the streets and seized control of the Sadr City neighborhood of Baghdad, and the cities of Al Kut, Karbala, and Najaf. Coalition forces were able to regain some control of these areas by May, but in cities like Najaf, the Mahdi Army never really left. In August, coalition forces launched operations to defeat non-compliant forces and neutralize destabilizing influences in Najaf Province. The 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit, supported by army units including the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry (2-7 Cavalry), conducted operations in Najaf. During the three weeks of fighting, the American forces killed an estimated 1,500 al-Sadr militiamen while suffering minimal casualties. As a result, Muqtada al-Sadr brokered a truce with the Iraqi government on August 27.

Despite national negotiations with civilian leaders and the activities of the Fallujah Brigade, Fallujah became an insurgent safe haven from which they launched attacks around the country. Violence in and around Fallujah continued to increase throughout the summer. By September, the coalition had had enough and authorized the planning for an assault into Fallujah to eradicate the extremist insurgent nest and assigned the mission to the 1st Marine Division.

In late October, the 1st Marine Division started marshaling forces and reinforcements for what would become Operation Phantom Fury: the second battle of Fallujah. By the end of October, coalition forces had convinced most of Fallujah’s civilian population to depart, leaving as few as 500 civilians remaining in the city when the battle began. Operation Phantom Fury, later renamed Operation al-Fajr (Arabic for Dawn), took place from November 7 to December 23, 2004. Eighty-two United States servicemembers were killed and more than were 600 wounded during the operation.

The 1st Marine Division’s two main units that executed Operation al-Fajr included Regimental Combat Team 1 (RCT-1) and Regimental Combat Team 7 (RCT-7). RCT-1 was comprised of two Marine infantry battalions—3rd Battalion, 5th Marines and 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines—and Task Force 2-7 Cavalry. RCT-7 consisted of two Marine infantry battalions—1st Battalion, 8th Marines and 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines—and U.S. Army Task Force 2-2 Infantry. Each RCT also included engineers, military police, logistics, and other support elements.

In this chapter, John Spencer interviews Lieutenant General James Rainey about his role in this battle. At the time of the interview in 2021, General Rainey was serving as the commander of the Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth. In November 2004, Rainey was a lieutenant colonel, and commander of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment within the 1st Cavalry Division. For the duration of the Second Battle of Fallujah, Task Force 2-7 Cavalry was under the operational control of the RCT-1.

John Spencer: Prior to the second battle of Fallujah you were in Najaf, Iraq and that was where you and Task Force 2-7 Cavalry honed many of your urban warfare tactics, techniques, and procedures to clear terrain and defeat enemy forces. Can you talk a little about your experience in Najaf and how the first battle of Fallujah impacted operations?

James Rainey: I was not involved in the first battle of Fallujah. I think it was largely political pressure from the Iraqi government that caused the attack to be called off. A lot of people have written about it, but it was my sense that it was politics that forced the battle to be ended prematurely. That is important because remembering those political concerns was always in the background as we prepared for the second battle of Fallujah. The pace, sense of urgency, and tempo that Marine Corps senior leaders set for the second battle of Fallujah was informed or influenced by their experience with that lack of political will from the Iraqi government during the first battle.

Turning to Najaf. Yes, we gained some valuable experience in urban fighting there, but the 1st Cavalry Division’s pre-deployment training also prepared us as well. General Peter Chiarelli, the division commander, and our brigade commander, Colonel John Murray, who is now a general and commanding the U.S. Army Futures Command, made our pre-deployment training hard and specific. We knew that we were going to fight in the city—we were going to Baghdad—so we trained hard, and we were ready.

The division’s 1st Brigade got into a fight in Sadr City almost immediately upon our arrival in Iraq and acquitted themselves incredibly well. It was Colonel Robert Abrams, Lieutenant Colonel Gary Volesky, and their units. So, we were all well trained, but you can, of course, always get better. In Najaf, fighting with the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit, our staff and I learned a ton about fighting as part of a joint (multiservice) force: interoperability, how to leverage fires, how intelligence systems work, and how commanders talk to each other on the battlefield. So, the experience we gained in Najaf was extremely useful for the Second Battle of Fallujah.

Spencer: When did your battalion get notified that you would be supporting the Fallujah operation?

Rainey: I think it was about the 3rd of November when I received the call. Task Force 2-7 Cavalry was part of the “Grey Wolf” Brigade (3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division). We were attached to the 39th Infantry Brigade Combat Team and based at Taji (a rural district just north of Baghdad). We had gone down to Najaf, fought, came back, and then received the warning order to be prepared to move by ground from Taji to Fallujah to link up with the Marines.

Spencer: When did you actually get to the Fallujah area?

Rainey: The first thing I did was put our operations officer, Tim Karcher; our intelligence officer, Mike Irwin; and our fire support officer, Coley Tyler on a helicopter to the Marine headquarters to start the planning process. Cross-attaching units—especially in combat—is always sporty but doing it across services is even more complex. We had to conduct a pretty significant move from our base at Taji to Fallujah, that included going around Baghdad. There is not much stealth in moving a mechanized task force around, so the Marines masterfully acknowledged that challenge and incorporated our move into their information operations plan to get us there. It took about four days to get the entire task force into our assembly area north of Fallujah.

Spencer: I know that the enemy situation between the first and second battles of Fallujah was vastly different. What was the enemy situation in Fallujah in November of 2004?

Rainey: Intelligence is never 100 percent accurate, but I would say we had somewhere between a 50 to 70 percent read on the enemy. We were not sure about the total number of enemy fighters within the city. However, because of an effective information operations campaign, pressure exerted by the Marine cordon, and some pretty effective humanitarian and civil affairs work, we felt that the city was largely void of civilians. By contrast, when I fought in Najaf and Baghdad, there was always a mix of friendly, enemy, neutral, and people who looked neutral or friendly but were actually enemy. Civilians on the battlefield always complicate the fighting. But we felt that the innocent civilians had moved out of the city and the only people remaining were going to fight and fight to the death. It very much had a last stand type of feel to it.

Spencer: I know it has been a while, but what was the overall mission for the second battle of Fallujah?

Rainey: The purpose of the operation was to deny or eliminate Fallujah as a safe haven for the enemy. The Sunni insurgents used Fallujah as a sanctuary to plan attacks, conduct meetings, and command and control their operations. They had numerous improvised explosive device (IED) factories and vehicle-borne improvised explosive device factories in the city. So, the purpose was to take away their sanctuary and their freedom of action. The specific mission, our part—well, RCT-1’s part—was enemy oriented: destroy the enemy force in the initial phase; conduct a detailed clearance in the next phase; and transition to setting the conditions for good governance, restoring essential services, and establishing stability in the final phase. But the initial mission was enemy oriented.

Spencer: What was the main plan of attack for the entire element? I know that the attack included more than just RCT-1.

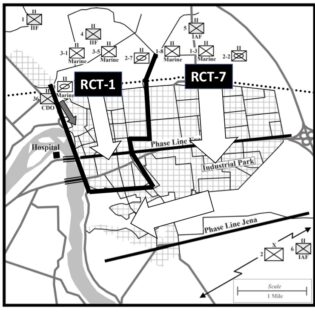

Rainey: The Marines had already established a cordon around the city, so the plan was to start with shaping operations conducted using fires and information. The 1st Marine Division, consisting of two regimental combat teams, would then attack from north to south. Initially RCT-1 would be the main effort to seize about 25 percent of the city, and then RCT-7, as the follow-on main effort, would clear from north to south and then east to west, the remaining three quarters of the city. That, like always, is not exactly what happened, but that was the initial plan (see figure).

Source: Map is modified from map 3 in Gott, Eyewitness to War.

Spencer: And each RCT had an army mechanized battalion as the lead element?

Rainey: They were what we would call a combined arms battalion now. Our battalion, Task Force 2-7, was assigned to RCT-1, and Task Force 2-2 was assigned to RCT-7. We were basically an infantry-heavy mechanized task force with two mechanized infantry companies and one tank company.

Spencer: Were you the main effort for the operation?

Rainey: Yes, Task Force 2-7 was the main effort for RCT-1 and RCT-1 was the main effort for the 1st Marine Division; at least for the initial phase of the attack.

Spencer: And what was your mission?

Rainey: Our task was to penetrate with its purpose to disrupt the enemy’s defense so that the two Marine Infantry battalions, who would be conducting the house-to-house clearing, would not have to fight against an enemy in a strong defensive posture. So, our mission was to dislocate the enemy’s defense and put them in motion so that they could not fight a deliberate delaying defense against the Marines who had to clear enemy forces in zone. RCT-1’s plan called for a very narrow avenue of approach. Focusing our battalion on a narrower front resulted in a very deep and rapid penetration that dislocated the enemy’s entire defense. It put the enemy in motion, forced them to leave many of their defenses, and gave the Marine infantry battalions the initiative.

Spencer: In reading about the planning process for this mission, I read that when you sent your planning team to the Marine headquarters, there were conversations about understanding the use of mechanized units in urban terrain. During the conversation your operations officer said something to the effect of, “When you unleash a heavy mech battalion like this in the city, it’s going to be Armageddon,” meaning there would be additional collateral damage to the terrain based on the firepower of the mechanized units.

Rainey: Yes. From the onset, I felt we needed capability briefs so that we all understood each other’s capabilities. The Marines had M1 Abrams tanks and knew what tanks could do but employed them differently from the Army. The Army fights tanks as companies of tanks as opposed to the Marines which use tanks in a direct supporting role to the infantry. So, we had to deal with some of those conceptual differences. Each service brought immense capabilities and skills and it was important to identify, discuss, and understand them.

One thing the Marines know well—and they have a bit of an advantage because they are almost joint by nature—is ground-air integration. They had significantly more experience employing joint fires, with the exception of army attack aviation, than us. There was a lot of mutual learning of how to get our targets prosecuted when we had a joint stack (many layers of aircraft above an objective area) of seemingly unlimited assets. But it all came down to whether our joint fires guys had the right radios and the right procedures to leverage those fires. So, there was a lot of back and forth.

When I think about the second battle of Fallujah, to me it was a textbook example of how to bring together a joint force. What right looks like. We all go to school, we see the line of block charts of joint task organizations, and we all inherently know that we fight as part of a joint force. But in my career, that fight was the most effective that I have ever seen come together. It was a great example of when the United States military comes together and puts all the pieces together as a joint force, the result can be incredibly powerful.

Spencer: After you had received your mission and started conducting your mission analysis, you requested some additional assets. What were those?

Rainey: The 1st Cavalry Division leadership, Colonel Murray and General Chiarelli, told me that they would give me whatever I needed. I knew the rules of engagement and the law of armed conflict, but I also knew that in an urban environment, questions—such as what is acceptable in terms of collateral damage—are more common and more profound, so I asked for an operational law lawyer since Army battalions do not have a lawyer assigned, and I received one. I also asked for another company. The division did not have one that they could give me, but I did get permission to bring a sizable portion of a company from the Oregon National Guard’s 162nd Infantry Regiment, that was located in Fallujah, with me. I also asked for Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTACs) form the air force. They were a precious asset—experts at calling in bombing missions from air force, navy, and Marine aircraft—and there were never enough for everybody. True to his word, General Chiarelli provided me with some JTACs that were assigned to the division. So those were three big ones.

Spencer: One thing that I found interesting about this battle was how the mechanized infantry and tanks were used. It may not be completely reminiscent of the drive to Baghdad during the 2003 invasion, but as I go through the steps of a doctrinal deliberate attack—isolate, breach, seize a foothold, clear the objective—that is not what I saw happening here. Your battalion penetrated deep into the city without doing a house-by-house search to get there. And, I believe, you did not dismount your infantry unless necessary; the tanks led the penetration. In other battles that I have studied, like the Battle of Aachen in World War II, dismounted forces were employed with or even in advance to protect the armored vehicles.

Rainey: Yes. The Marines had a great plan. I cannot overstate the fact that the operation was a well-planned, well-rehearsed, integrated, joint operation and the two large infantry battalions basically cleared in zone. They cleared the buildings and destroyed the enemy. So, if you take a mechanized force, whose strength are tanks and Bradleys—mobility, protection, and firepower—why would we dismount those couple squads and clear two floors of a building? It would exhaust our combat power and slow the penetration. That was a job for the Marines. They had large infantry squads, were very good with mortars, and they were optimized for close-in fighting.

One reason the plan was so successful is because of exactly what you said. Our job was to penetrate. We penetrated rapidly to the middle of the city during the first period of darkness, leading with tanks because that was where the firepower, survivability, and speed of our formation was located. If the enemy wanted to hide, we bypassed them; if they wanted to fight, we killed them.

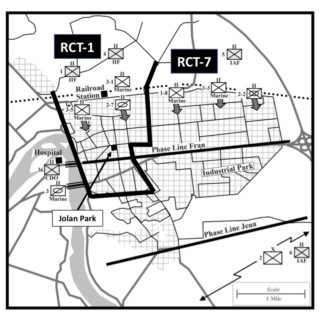

Our goal was to reach Jolan Park, a big giant park in the middle of the city (see figure). The park even had a giant Ferris wheel which was kind of creepy in a combat zone. The intelligence team determined that the enemy’s most likely course of action was to defend against us from all around the city. Once they figured out where our main attack was occurring, they would delay us there while the remainder of their force would fall back to that park and defend there. So Alpha Company, 2-7 Cavalry attacked along four or five roads right towards that park, destroyed the enemy force that was there, was there before the main enemy groups could fall back, and we were waiting to destroy them when they did. At the same time Charlie Company, 3-8 Cavalry, our tank company, attacked right down the main road, destroying the enemy as they came out to fight.

Source: Map is modified from map 4 in Gott, Eyewitness to War.

Multiple threats

By morning, we had secured the park. The enemy was then facing a large, mechanized formation that commanded the center of the city and controlled all the roads leading into it with fires. One of my mechanized infantry companies was located at what I believe was their decisive point. Instead of falling back to defend, they now had to deal with multiple threats.

Simultaneously, the same thing happened in RCT-7’s sector. Multiple small units of very lethal and well-trained Marines were pressing the enemy in multiple directions. It disjointed the enemy. What I learned from the attack and what we also discovered in Najaf, was that if you could penetrate an urban area and get somewhere you could defend, the enemy must come to you. And that is what you want. You want the enemy moving to you versus you having to root them out of well-prepared defensive positions.

Spencer: Your battle in Najaf, this one, the fight for Baghdad with General Perkins were all similar: conduct a deep penetration to get in there and hold terrain within the enemy zone. It does start to shape my own thinking about the successful tactics of an operation like this.

Rainey: It is important to remember that we were a joint force. We were successful because we had fires, we had intelligence, we had all of it. There are risks with penetration-type tactics in urban areas because if your force gets cut off then you have some serious problems. Wherever you go, you have to hold at least enough of a line of communication to resupply yourself, evacuate casualties, and things like that. When we penetrated the city, we continued to hold the road that we used to conduct the penetration. So, in a combined arms battalion like ours, we had the tanks’ shock, speed, firepower, and protection. We also had mechanized infantry which had vehicles that basically exist to position our rifle squads. It was very different from a light infantry unit, or the Marines that we were fighting with. The Marine squads were breaching and clearing floor by floor, room by room.

The infantry that comes with the mechanized formation largely exists to protect the tanks and Bradleys from the enemy’s dismounted infantry. So, we would penetrate and then dismount our rifle squads. They had to fight in the buildings too, but only for a specific purpose and we did not have to clear every building along our route. The infantry breached into buildings, cleared what they had to get observation of the road, and emplaced snipers to support the advance. All of this was to protect the vehicles from the enemy’s fighters who might be maneuvering against the armor formations, because tanks are vulnerable in an urban area.

If the enemy can get close, they can hurt the tanks. The urban space gave the defender all kinds of “keyhole” shots. We lost six tanks in Fallujah. A couple ran over mines, but most of them were disabled by rocket-propelled grenade volley fire. They did not, however, get a catastrophic kill on any of the tanks or hurt any of the soldiers inside them, but they did penetrate gun tubes, blew off tracks, blew vision blocks into the turret, and things like that. Urban warfare requires combined arms capabilities.

You have to have the ability to rapidly penetrate, which takes speed, protection, and firepower. There were IEDs in Fallujah but not to the extent that we would see if someone was defending against an attack by the United States in an urban area today. For example, there were no drone swarms back then. There are going to be a lot of new challenges in the future. If you have to fight in an urban environment, you want everything. You want tanks that can penetrate. If you want tanks, then you have to have infantry to protect them. If you want infantry to protect them, then you have to have infantry fighting vehicles to position your rifle squads. You need a mix between a lot of firepower, a lot of mobility, and a lot of protection. It requires both tanks and rifle squads on the ground. Rifle squads have to be lethal; they have to be well trained; and they have to know how to fight and execute battle drills.

It also requires great intelligence. It requires fires, which can be challenging to employ in urban environments, so you may have to be artful in their employment to minimize collateral damage and the risk to civilians. There are also medical and logistic challenges, which are a challenge in any fight, but they are like ten times more complex in an urban area. There are many challenges associated with urban warfare.

Spencer: I think the use of fires in support of maneuvering forces is really important. Could you talk about some of the joint fires that you had available to you, everything ranging from AC-130 gunships to unmanned aerial systems. Some people might point to this battle as one of the first times that the United States used unmanned aerial systems to such an extent to identify enemy positions and provide the intelligence to conduct effective fires during an operation.

Rainey: Fires were very centralized for the shaping operations and the division and the RCTs planned and executed the fires. Because the enemy was doing things like building fighting positions, digging in, emplacing IEDs, that created the conditions within the law of armed conflict and the rules of engagement to use fires during the shaping operations. You cannot just blow up a building, but if the enemy builds a fighting position in the building and is occupying it, then it becomes a legitimate target.

The battle of Fallujah was the biggest priority in Iraq for the United States military, so we were given an array of assets. Our battalion had priority of fires from an AC-130 gunship, for example, during the penetration that first night. As opposed to not having enough fires capability, we had so much that the ability to deconflict it was our challenge—an interesting and good problem to have. We have made significant progress on joint interoperability over the past decade and a half, but at the time, Captain Tyler and his crew had a lot on their hands. The JTACs were great at talking to the air force aircraft and they were pretty good at talking to navy aircraft, but the army forward observers had to rapidly learn how to effectively get targets prosecuted through the Marines’ systems.

It also worked the other way around with army systems supporting the Marines. The 120 mm mortars that we had during the fight were major killers on the battlefield. The Marines have a lot of mortars, but at the time, they did not have the 120s. The challenge with shooting artillery into a city is the low trajectory of the round. You may not be able to fire artillery rounds at your desired target because it may be blocked by another building. Mortar rounds travel at a higher trajectory and can go over the buildings that are in the way of the artillery. Mortar rounds can come down right on the top of a building or in between two buildings. Over the course of the battle the Marines learned how to get fire missions to the Army 120 mortars and became very proficient.

Spencer: I will go ahead and read you my favorite quote from you about fires, because it really motivates me. In one of your post-battle interviews you said, “You can’t win anything without infantrymen on the ground physically taking it, but the easiest, most effective and least casualty producing on friendly forces way to fight an enemy, even in urban environments, is with fires.”

Rainey: Yes, I grew up as an infantryman, but I like to think of myself as a combined arms maneuver officer now as opposed to just a single branch officer. Infantry and fires are not mutually exclusive. Everybody in the army ultimately exists to put a rifle squad in a position of advantage to close with and destroy the enemy. Nobody wants to do that, but at the end of the day—and I think the history of war supports the idea—somebody always has to do the close-in, tough fight. Someone has to close that last 100 meters. In a contest of wills between humans, sometimes people must get killed. But, at the same time, any good maneuver officer is going to exhaust every resource at his or her disposal before they commit men and women to close-in fighting. So yes, my first solution to every problem is to exhaust other means before I decide to commit infantry or even armor forces. If I can get accurate intelligence and employ fires to destroy the enemy from a distance, I will.

Spencer: Well, sir, I really appreciate your time. There were some very important lessons that can be learned from the second battle of Fallujah that would support anyone’s leader development program or self-study. I found our discussion helpful as I continue my own development. Thanks a lot, sir.

Rainey: Yes, and thank you, John. One last thing; I would ask everybody to remember that we, the United States Army and Marines, paid a high price for a significant victory. The victory came at the cost of the soldiers and Marines who lost their lives in the battle, and I would just ask everybody to keep them all in their thoughts and prayers. I will and I hope others always remember that.

Liam Collins is the executive director of the Madison Policy Forum, a member with the Council on Foreign Relations and a fellow with New America. He also served as a defense advisor to Ukraine from 2016-2018. He is a retired U.S. Army Special Forces colonel with deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, Bosnia, the Horn of Africa, and South America. He is co-author of Understanding Urban Warfare. You can find him on Twitter, @LiamSCollins.

John Spencer is the chair of urban warfare studies at the Madison Policy Forum. He served 25 years as a U.S. Army infantryman, which included two combat tours in Iraq. Together, he and Collins traveled to Ukraine in June 2022 to research the defense of Kyiv. He is the author of the book Connected Soldiers: Life, Leadership, and Social Connection in Modern War and co-author of Understanding Urban Warfare. You can find him on Twitter, @SpencerGuard.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers