New Revelations about Vietnam Command Decisions

By Harold Hutchison

From the April 2014 issue of SOF

WHAT WE KNOW MAY NOT BE SO

Many “pop history” stories about Vietnam have gone around, and a general narrative on the war has taken hold among many who feel we could have won it. But how much of what we think we know about Vietnam isn’t so? The answer could be very surprising, as an interview with Lewis Sorley reveals. Sorley, the author of Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam, provides new insight into not just the Vietnam War but many of the key figures in that war, in which over 58,000 Americans died.

Many “pop history” stories about Vietnam have gone around, and a general narrative on the war has taken hold among many who feel we could have won it. But how much of what we think we know about Vietnam isn’t so? The answer could be very surprising, as an interview with Lewis Sorley reveals. Sorley, the author of Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam, provides new insight into not just the Vietnam War but many of the key figures in that war, in which over 58,000 Americans died.

Sorley’s latest book will likely join H.R. McMaster’s Dereliction of Duty as essential reading for those who want the truth about the Vietnam War. His account adds to the picture of how American leaders let down not only the troops who were sent to Vietnam but also the people of South Vietnam, who deserved far better than to fall under the domination of Communist North Vietnam.

Most ironic is that this is the seventh book by a person who never set out to write a book in the first place. Sorley’s writing career began as an effort to motivate the soldiers in his battalion, which at one time had been commanded by Creighton Abrams, who went on to command the Military Assistance Command Vietnam and to eventually be Army Chief of Staff.

LBJ’S MICROMANGEMENT… OR NOT

One of the big myths that Sorley shoots down in his book is that Westmoreland was micromanaged by Lyndon Baines Johnson. While it was true that President Johnson was responsible for micromanaging the war outside South Vietnam, especially in the notorious “Tuesday lunches,” where he would pick air bombardment targets, weapons used, and the routes to the target, Westmoreland didn’t have to deal with micromanagement.

“Inside South Vietnam, Westmoreland had almost complete freedom of action, which was also true for his eventual successor. Westmoreland chose to fight a war of attrition, using search and destroy tactics,” Sorley said. The use of the body count as the only “measure of merit” in the war was also Westmoreland’s decision, not President Johnson’s.

“Inside South Vietnam, Westmoreland had almost complete freedom of action, which was also true for his eventual successor. Westmoreland chose to fight a war of attrition, using search and destroy tactics,” Sorley said. The use of the body count as the only “measure of merit” in the war was also Westmoreland’s decision, not President Johnson’s.

Westmoreland was operating from the premise that he could break the will of the North Vietnamese with the body count. “If he could kill enough of the enemy, they would lose heart, cease their aggression against the South, and go home again. The war would then be won. It didn’t work out that way,” Sorley explained.

JOHNSON’S STORY

Sorley notes that one figure, now seen in a tragic light, may deserve better from history. That figure is then-Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson. Johnson, a 1933 graduate of West Point, served in the Philippines in World War II, survived the Bataan Death March and 41 months in Japanese POW camps, then served in Korea, where he earned the Distinguished Service Cross.

Johnson is at the center of what may be a case of embellished history. One of the most commonly told stories has General Johnson getting in his car and driving to the White House, where he contemplated resigning in protest of LBJ’s conduct of the Vietnam War. However, the truth of the matter – and Johnson’s choice to stay in – is far different.

Sorley interviewed Johnson’s driver in the course of his research. Johnson apparently never did make that trip, at least with his primary driver. Furthermore, the driver was never briefed on any such trip by any substitute driver, which would have been almost a standing operating procedure. Two other details that should be noted: First, General Johnson’s stars were embroidered on his uniform. There was no way he could have unpinned them to hold them in his hand. Second, to see the president, Johnson would have needed an appointment – and if he had one, there was no way he could have ducked it.

Sorley interviewed Johnson’s driver in the course of his research. Johnson apparently never did make that trip, at least with his primary driver. Furthermore, the driver was never briefed on any such trip by any substitute driver, which would have been almost a standing operating procedure. Two other details that should be noted: First, General Johnson’s stars were embroidered on his uniform. There was no way he could have unpinned them to hold them in his hand. Second, to see the president, Johnson would have needed an appointment – and if he had one, there was no way he could have ducked it.

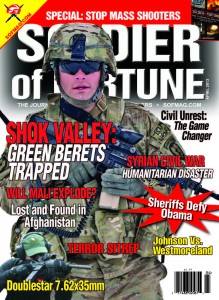

JOHNSON VS. WESTMORELAND

Johnson, it should be noted, was aware that Westmoreland’s strategy was badly flawed. The use of unobserved artillery fire and large-unit sweeps and constant requests for additional troops were creating more and more concern for the Army Chief of Staff. Johnson made repeated trips to the theater of operations, as did officers carrying out a study.

Johnson’s concern had started as early as 1965, when he saw what forces were being requested. It had started with two Marine battalions in March of that year, then grew to the 173rd Airborne Brigade in May, with the 1st Cavalry Division being sent later that summer. Johnson spent months trying to convince Westmoreland to change his strategy, but Westmoreland refused. “After not succeeding in changing the commander’s methods, Johnson decided to change the commander. Creighton Abrams was sent to be Westmoreland’s deputy in May 1967, with expectation he would take over in a few weeks.”

But the change would take much longer. Why the change took 13 months is open to some conjecture. Sorley, however, has a rough idea of how that change may have been delayed, and it centers on a comment made by Robert McNamara in July 1967, two months after Abrams arrived in Vietnam.

A SUBTERFUGE BREAKS DOWN

Usually to manage the war, the commanders would meet with the president and secretary of defense – often in Honolulu, Hawaii, but sometimes in D.C. or Manila. McNamara also made a number of trips to Vietnam, and it was during one of those trips that the plan to replace Westmoreland would be delayed.

During the July 1967 visit, McNamara made a comment along the lines that the commander on the scene needed to make better use of the troops he had. This was not the normal way those meetings had gone. Usually, Westmoreland would request an amount of troops, it would be discussed with McNamara and they would agree on a smaller number that Westmoreland would formally request from LBJ. This allowed the president and secretary of defense to say they were giving Westmoreland all the troops he had asked for.

But McNamara’s comments in July 1967 put the removal of Westmoreland on hold. Westmoreland complained about McNamara’s comments to LBJ, and the thin-skinned LBJ probably felt sympathy for Westmoreland. In point of fact, LBJ wasn’t the type of person to replace a commander who was under criticism. Westmoreland would stay in command for an extended period of time.

A TELLING COMMENT FROM AN ANCHOR

A TELLING COMMENT FROM AN ANCHOR

Westmoreland was not completely out of his depth. Prior to the Tet Offensive in January 1968, he was willing to listen to commanders whose intelligence suggested that there was going to be a major attack around Saigon. One of those commanders was then-Lieutenant General Fred Weyand, commander of II Field Force. Weyand kept his troops close enough to respond quickly to the requests for help.

Sorley also relates how Weyand would come up front against a man who had decided he would work to end the war, despite the facts. When Walter Cronkite came to Saigon after the Tet Offensive, Weyand gave the CBS anchor a very detailed briefing. Cronkite’s incredible response was, “Well, General, I’m not going to use any of this in my report because I’ve decided I’m against this war, and I’m going to do everything I can to bring it to a halt.”

In a real sense, Cronkite’s effort to end the war may well have been aided by Westmoreland’s participation in the 1967 “Progress Offensive,” in which he spent much time in the United States trying to convince people that the war was going well. One statement that must have come back to bite him was “We have reached the place where the end begins to come into view.”

THE END FOR WESTMORELAND

THE END FOR WESTMORELAND

When the Tet Offensive exploded all across South Vietnam and on the TV sets of America, it was a devastating blow for Westmoreland. As Sorley put it, “Many Americans concluded that either Westmoreland had not known what he was talking about or he had not leveled with them.” Sorley observed that it was hard to know which was the more devastating criticism.

Westmoreland would turn command over to Creighton Abrams in June 1968. Abrams would put into practice the recommendations made by the study Johnson had initiated in 1965, but over two years had been lost. Westmoreland’s reliance on the flawed “body count” metric led him to claim that the Tet Offensive was an American victory, but it may have been a hollow victory. Westmoreland’s request for 206,000 additional troops also didn’t help matters.

Westmoreland’s command tour is well worth examining. The facts about the Vietnam War can still come out, decades after the last American soldier left that country. Sorley’s book is well worth the read. A paperback version was released in October 2012.

Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 416 pp., $30

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers