by Susan Katz Keating

2006

The traffic along Georgia Avenue going south was sparse throughout the stretch of Maryland road. The bus proceeded unhindered, ferrying wounded warriors strapped into gurneys or propped up with i.v. lines attached, and belted into seats. Many were profoundly changed men and women with missing limbs or with head injuries that left them with varying degrees of disability. They all were heading from one military facility to another; from the naval hospital where they had surgery or other immediate care, to the Army hospital where they would recuperate.

As the bus crossed into the District of Columbia, the surroundings gradually began to change. First came heavier traffic, as the neighborhoods alternated from business districts to old row houses and back, and finally to the vast expanse alongside Walter Reed Army Medical Center. As the bus made the turn into Walter Reed, to safe harbor, the warriors encountered a horrific welcome. They would suffer a phalanx of ghouls, including anti-military activists splashed with fake blood while dressed in Grim Reaper costumes, standing alongside mock coffins, and holding signs emblazoned with appalling messages: “Maimed for a Lie” and “Enlist here to die for Halliburton.”

That October Friday night on the bus, the passengers may not have expected such a scene. But one former Vietnam-era Marine, “Concrete” Bob Miller, did. He was part of it; the part that hated the ghouls.

As the bus continued south toward the District at sundown, Concrete Bob parked his big black truck in a lot behind the row houses across from the hospital. He walked across Georgia Avenue, and approached the Walter Reed main gate. In his light-washed blue jeans, black t-shirt, and cowboy boots, the mustachioed Bob seemed out of place in the nation’s capital, where even the most casually dressed locals don’t wear rancher gear.

READ MORE from Susan Katz Keating on veterans helping other veterans

The goblin-garbed protestors stood smirking alongside their prop coffin. Perhaps they thought the fast approaching Bob easily would be dispatched.

Raised in Virginia, Bob was a bona fide hippie during the Vietnam War. Back then, he wore flowing locks, love beads, and bell bottoms, he told me, until he joined the Marines. He spent his service in Panama, and came home with an unyielding respect for the military. He helped form a charity organization, Cooking With the Troops, and recruited me as a board member. Our group gave voice-activated laptops to wounded warriors, and held cookouts for service members and their families both overseas and at home.

Many of us were involved with CWT, but Bob was the driving force. He personally prepared all the smoked meats, and brewed our signature barbecue sauce from an old family recipe. Most of all, he was the charming, gregarious front man for our mission. Although he spoke with a pronounced Virginia drawl, country-boy Bob was no rube. He was keenly sharp and energetic, and he tolerated no disrespect for the troops. Which is what he saw that night when he approached the gates of Walter Reed.

Bob did not confront the protesters. He ignored their snide shouted comments. He strode past them onto the hospital grounds – with me alongside him.

When I asked if he heard the ugly remarks, Bob answered in graveled tones: “Mmm, hmmm.” Then he stationed himself at our table, amid the throng of other morale-boosters: athletes, celebrities, club members, diplomats, and off-duty National Guardsmen. With a smile that never faded, Bob handed out treats. He chatted with patients, nurses, and caregivers.

The bus from Maryland turned inside the gates. Bob and I heard the jeers from outside.

The vehicle pulled slowly forward atop the speed bumps, the driver careful not to jar the passengers on their gurneys or with their i.v. lines attached. Bob waved cheerfully.

We couldn’t see the passengers disembark, but Bob shouted at them through cupped hands: “Welcome home, brothers and sisters! Good to have you back!”

We and the others – the athletes, celebrities, club members, diplomats, and off-duty National Guardsmen – remained until after dark, when the protesters packed up their coffins.

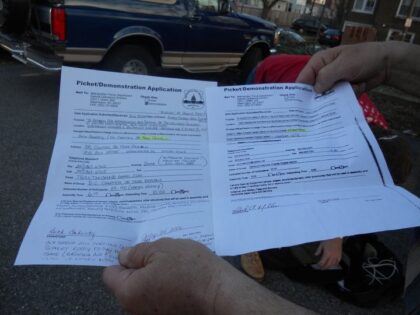

The following Monday, Bob visited the D.C. city government offices. He asked a clerk: “When does the Walter Reed demonstration permit expire?”

The clerk responded that no one had a permit.

Bob instantly secured one for himself.

The following Friday, permit in hand, Bob informed the protesters that they were in his spot. According to law, the ghouls had to vacate. Immediately. The group didn’t like it. They argued. But they gathered their signs and their coffin, and shuffled along the sidewalk to the nearest spot the police would allow. There, the agitators continued to stage their morbid, but far less visible, theatrics.

From that night forward, Bob and his fellows stood every Friday night at the main gate holding “thank you” signs, waving to each new bus as it arrived at Walter Reed. We sang songs, clapped, and stirred up a cacophony of passing motorists to honk their horns in solidarity. Depending on the night and the occasion, our group included members of the New York City Fire Department, actors Gary Sinese and Jon Voight, a Super Bowl alumnus athlete, an official from the Iraqi government, diplomats from the Czech Republic Embassy, and recovering wounded warriors.

Bob often texted me from the road to say, “You on your way?” Often I was, and arrived to find Bob in the street, directing me toward a parking spot he’d marked off with traffic cones. Pentagon and service officials remained silent – but quietly praised us for our efforts.

One night in December 2009, nearly 1,000 supporters joined Concrete Bob at the gates. As we stood at our table doling out barbecued chicken, Bob turned to me. “This is what I’m talking about, right here,” he said. “Supporting the troops.”

Years later, the buses don’t ferry their precious human cargo southward from Maryland along Georgia Avenue. Aside from rare events, American troops are not wounded in action. Walter Reed hospital moved to a new home run by the Navy in Bethesda. The old Army facility now is a planned residential and business community.

The athletes and celebrities have moved on, and so has our class of wounded warriors. One became a popular meme, depicting can-do spirit. Another wrote a successful autobiography – with a foreword from Gary Sinese.

The effects from the protests linger. Kevin Pannell, an amputee and former patient at the old hospital, perviously had this to say about the protests:

They were “probably the most distasteful thing I had ever seen. Ever. We went by there one day and I drove by and [the anti-war protesters] had a bunch of flag-draped coffins laid out on the sidewalk. You know that 95 percent of the guys in the hospital bed lost guys whenever they got hurt and survivors’ guilt is the worst thing you can deal with.”

Others, particularly family members, told me they never will forget the shocking cruelty and disrespect they encountered outside the gates of Walter Reed.

Concrete Bob lives, but only in memory. He died a few years ago, and our group disbanded Cooking With the Troops. His legacy is a powerful counterbalance to the ugly antics of the ghouls and their cohorts.

He gave us this much: a heady and purposeful time for Americans to show our love for the warriors.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor in chief of Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers