by Friedrich Seiltgen

They flew low, slow, and into heavy fire. In Vietnam, Forward Air Controllers were eyes in the sky, helping to prosecute battles, and saving lives with their accurate, real-time intelligence. In the process, three performed with such heroism that they were awarded the Medal of Honor. Here’s why.

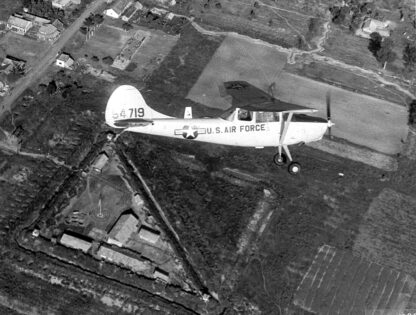

Captain Hilliard A. Wilbanks, February 24, 1967, Dalat, Vietnam, O-1 Bird Dog

Medal of Honor Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. As a forward air controller, Capt. Wilbanks was the pilot of an unarmed, light aircraft flying visual reconnaissance ahead of a South Vietnam Army Ranger Battalion. His intensive search revealed a well-concealed and numerically superior hostile force poised to ambush the advancing Rangers.

READ MORE on Forward Air Controllers:

The Viet Cong, realizing that Capt. Wilbanks’ discovery had compromised their position and ability to launch a surprise attack, immediately fired on the small aircraft with all available firepower. The enemy then began advancing against the exposed forward elements of the Ranger force, which were pinned down by devastating fire. Capt. Wilbanks recognized that close support aircraft could not arrive in time to enable the rangers to withstand the advancing enemy onslaught.

READ MORE: Forward Air Controllers Called in Fire From Above in Vietnam

With full knowledge of the limitations of his unarmed, unarmored light reconnaissance aircraft and the great danger imposed by the enemy’s vast firepower, he unhesitatingly assumed a covering, close support role. Flying through a hail of withering fire at treetop level, Capt. Wilbanks passed directly over the advancing enemy and inflicted many casualties by firing his rifle out of the side window of his aircraft. Despite increasingly intense antiaircraft fire, Capt. Wilbanks continued to completely disregard his own safety and made repeated low passes over the enemy to divert their fire away from the rangers.

His daring tactics successfully interrupted the enemy advance, allowing the rangers to withdraw to safety from their perilous position. During his final courageous attack to protect the withdrawing forces, Capt. Wilbanks was mortally wounded, and his bullet-riddled aircraft crashed between the opposing forces.

Captain Wilbanks’ magnificent action saved numerous friendly personnel from certain injury or death. His unparalleled concern for his fellow man and his extraordinary heroism were in the highest traditions of the military service and have reflected great credit upon himself and the U.S. Air Force.

Captain Steven L. Bennett, June 29, 1972, Quang Tri Province, Vietnam, OV-10 Bronco.

Medal of Honor Citation:

Capt. Bennett was the pilot of a light aircraft flying an artillery adjustment mission along a heavily defended segment of route structure. A large concentration of enemy troops were massing for an attack on a friendly unit. Capt. Bennett requested tactical air support but was advised that none was available. He also requested artillery support, but this, too, was denied due to the close proximity of friendly troops to the target. Capt. Bennett was determined to aid the endangered unit and elected to strafe the hostile positions.

After four such passes, the enemy forces began to retreat. Capt. Bennett continued the attack, but as he completed his fifth strafing pass, his aircraft was struck by a surface-to-air missile, which severely damaged the left engine and the left main landing gear. As fire spread in the left engine, Capt. Bennett realized that recovery at a friendly airfield was impossible. He instructed his observer to prepare for ejection, but was informed by the observer that his parachute had been shredded by the force of the impacting missile.

The Air Force gave new dog tags to Bennett’s daughter after the original tags went missing.

Although Capt. Bennett had a good parachute. He knew that if he ejected, the observer would have no chance of survival. With complete disregard for his own life, Capt. Bennett elected to ditch the aircraft into the Gulf of Tonkin, even though he realized that a pilot of this type aircraft had never survived a ditching. The ensuing impact upon the water caused the aircraft to cartwheel and severely damage the front cockpit, making escape for Capt. Bennett impossible.

The observer successfully made his way out of the aircraft and was rescued. Capt. Bennett’s unparalleled concern for his companion, extraordinary heroism, and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty, at the cost of his life, were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Air Force.

Col. George “Bud” Day, August 26, 1967, North Vietnam, F-100F Sabre.

Medal of Honor Citation:

On 26 August 1967, Col. Day was forced to eject from his aircraft over North Vietnam when it was hit by ground fire. His right arm was broken in three places, and his left knee was badly sprained. He was immediately captured by hostile forces and taken to a prison camp where he was interrogated and severely tortured.

After causing the guards to relax their vigilance, Col. Day escaped into the jungle and began the trek toward South Vietnam. Despite injuries inflicted by fragments of a bomb or rocket, he continued southward, surviving only on a few berries and uncooked frogs. He successfully evaded enemy patrols and reached the Ben Hai River, where he encountered U.S. artillery barrages. With the aid of a bamboo log float, Col. Day swam across the river and entered the demilitarized zone. Due to delirium, he lost his sense of direction and wandered aimlessly for several days.

After several unsuccessful attempts to signal U.S. aircraft, he was ambushed and recaptured by the Viet Cong, sustaining gunshot wounds to his left hand and thigh. He was returned to the prison from which he had escaped and later was moved to Hanoi after giving his captors false information to questions put before him. Physically, Col. Day was totally debilitated and unable to perform even the simplest task for himself.

F-100F Super Sabre Misty FAC flying in Southeast Asia in July 1968. (U.S. Air Force photo).

Despite his many injuries, he continued to offer maximum resistance. His personal bravery in the face of deadly enemy pressure was significant in saving the lives of fellow aviators who were still flying against the enemy. Col. Day’s conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Air Force and reflect great credit upon himself and the U.S. Armed Forces.

~ ~ ~

In 1973, after five and a half years of beatings, torture, and interrogations, Day was released. Although in terrible medical condition, Day was determined to return to duty. A year later, he qualified in the F-4 Phantom and was back on flight status.

Friedrich Seiltgen is a retired Master Police Officer with 20 years of service with the Orlando Police Department. He conducts training in lone wolf terrorism counterstrategies, firearms, and active shooter response. Contact him at [email protected]. He writes frequently for Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers