Editor’s note: Longtime CIA covert operations officer James Parker Jr. often talked to me about his days in Southeast Asia, including the secret war in Laos. He told stories of another case officer and former Green Beret, George Washington Bacon III, who became a mercenary in Angola. Here is an excerpt from Parker’s writings, which include Battle for Skyline Ridge: The Secret CIA War in Laos. In the following segment, he writes about Bacon, the legendary agent “Kayak.” ~SKK

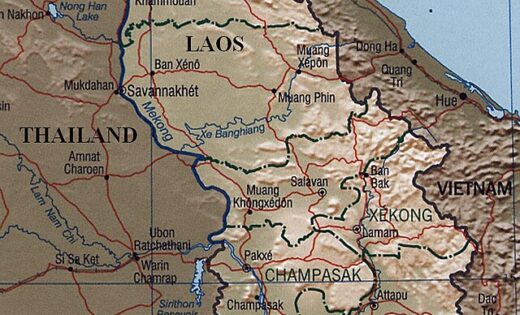

In northeast Laos, which had 600 miles of frontage on North Vietnam, the only American presence on the ground at any one time was a dozen or so CIA paramilitary case officers working with local guerrillas. Some came to work this remote, dangerous job from the Montana smoke jumper corps, who had years of experience working with planes in mountains similar to those in this area. This group was, to the man, hardy, rugged no-nonsense cowboys. An individual known in the CIA as “Hog” came from this group. Others came from combat tours in Vietnam, including “Kayak.”

Men assigned to Long Tieng, the CIA headquarters in northeast Laos, tended to stay for years. If they were ex-smoke jumpers, they came in on contract to do mostly aerial delivery chores and then just hung around getting their contract extended time and again.

If they came in because of their Vietnam combat experience, they had to pass general muster for work inside the CIA, the entrance requirements for which were tough. Men had to test high on intelligence and general perception, show some acumen for logic and demonstrate communication skills. They had to have upstanding character with no experiences in their past like arrests or anything akin to anti-social behavior. They had to demonstrate a sense of citizenship and ability to keep secrets. Plus they had to show some natural talent for combat, some tolerance for stress and some interest in taking risks. They had to do well in interviews with CIA paramilitary staff.

Thousands applied. Only a handful were hired.

READ MORE about Ric Prado, CIA Covert Warrior Who Stepped Out of the Shadows.

Laos may have been the best assignment, because the CIA ran a full-blown war in that country. In Laos, Long Tieng might have been the top pick because the “big fight” was happening there.

But since paramilitary types tended to stay on for years, there was rarely an opening—until 1970 when there was, by Long Tieng standards, a large scale re-assignment of personnel. Maybe 10 new paramilitary people arrived from that summer through the summer of 1971. Plus, because the pace of the fighting was picking up, more case officers were coming in with their troops from other parts of Laos.

Kayak was one of those selected out of training for Long Tieng in the summer of 1970. Most didn’t question his background.

Life in the valley was stark. It was total immersion in the raw, unaffected Hmong mountain tribe culture. As much as anyone, Hmong General Vang Pao ran the joint, in that he went to war every day with his CIA partners. But Long Tieng was Hmong land. Dealing with the Hmong, new arrivals had to put aside normal judgments. If you dealt with the Hmong, you had to accept their way of doing things rather than judge them. Same with Air America crews and the mighty USAF Ravens. The old CIA vets (who were called “Sky” by the Hmong), you just had to accept.

Being new, Kayak pretty much had no value. People just weren’t interested if he made all-conference in football in high school or if his daddy was rich. Could he do the job was the thing. Kayak could do the job.

He was given enormously responsible work his first day. That was to work with a Regular Thai Army (RTA) unit that was assigned due north of the Long Tieng valley in a barren ridgeline called Ban Na, LS 15, a ridgeline that was under constant attack by elements of the North Vietnamese Army (PAVN) 165th Infantry Regiment, under command of Colonel Nguyen Chuong.

READ MORE about a Raven in Vietnam.

To “work” with that RTA unit meant he had to deal with Air America pilots as a first order of business every dawn. The Air America guys were mean sumbitches, some of ‘em. Many had been flying the unfriendly skies of Laos for years and learned to survive in a combat zone by being selective in taking risks. Sometimes very selective. Everyone knew that the Ban Na, LS 15 area was hot, and when this new, particularly young Sky replacement, with the Kayak call sign, came walking up and asked them to go there, they would ask about the situation and where exactly they were to go and what Kayak wanted them to do.

Some refused to fly for him. Others agreed and they began to spread the word that this guy Kayak had a set of balls on him. So be careful, they’d say, about where he wanted to go. He wouldn’t lie, but he wanted to go where people were shooting at each other and any helicopters within range.

There was an account early on where a local Southeast Asia VIP visitor went out to one of the Ban Na defensive positions. Soon after he arrived, the position began to receive a lot of mortar fire from the PAVN 165th unit, followed up by ground attacks. Maybe their intercept had picked up on the planned visit of the VIP.

Kayak was on that position or one nearby. During the morning, when things were especially hot, Kayak’s calm, steady conversation with a Raven directing fire from fast movers (USAF jets) in the area was the deciding element in breaking up the PAVN assault. Meanwhile, the VIP was almost hysterical in demanding that Air America come back and pick him up—which, of course, they were not going to do until things calmed down.

With the enemy repulsed, Air America helicopters went in to retrieve the VIP. The lead pilot said the man rushed onto the helicopter and, once they were in the air, rolled into a little ball on the floor of the chopper, enormously thankful to be alive. Later Kayak was picked up as calm and cool as you please.

The fighting at this location became so intense that, back in Washington, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger proposed sending in U.S. MEDEVAC helicopters with armed Huey escorts to evacuate the wounded and killed at that one position. In time, some helicopters arrived just to do that job, but Kayak continued his daily trips out (with pilots who would carry him) to spend time with the Thai troops, to coordinate with Raven support of USAF fast movers, then get in ammunition to the different positions where it was needed and to get wounded out and replacements in and, where possible, get friendly patrols out working in front of the wire. Day after day after day. Pilots noticed this guy Kayak never seemed afraid—fearless was the Air America reputation—to go anywhere and to do what was necessary, professionally.

Air America helicopter in Southeast Asia

The other case officers back in the valley noticed something about him, too—that he was pretty damn smart. It’s not like he was reciting poetry or talking physics all the time; it was that he picked up on new things without a lot of explanation. He remembered things first-time ’round. He didn’t talk a lot, but he listened carefully. He took note of everything happening around him. He remembered everything he heard. One just knew early on that this was a smart, perceptive dude.

At night he would come in and, in the general briefings to Chief of Unit Dick Johnson at the map board, he’d discuss what had happened out at that hellish place with almost a detached sense of danger. The bad guys attacked here, RTA guys yielded one bunker, but then took it back, one of their rounds landed on this bunker and some Thais were killed and wounded. All evacuated. Overall situation at dusk the same as it had been at dawn. That kind of thing. Kayak would have been in the center of things, but his report was not “point of view” as much as it was simply third person—this happened and then that. Dick was constantly telling Kayak to stay out of the line of fire.

In almost all accounts of close combat that involved Sky officers in the valley at that time, Kayak was in the thick of it: Plain of Jars when 27,000 North Vietnamese attacked; Skyline Ridge, working with a Hmong commando unit, retaking positions from North Vietnamese on the ridgeline. Fighting off enemy sappers on suicide missions in the valley.

From day one, Kayak was a fully formed paramilitary case officer. He was a unique individual, even among a group of outstanding individualists, in that he walked around most of the time with a tooth brush in his mouth, occasionally making a swipe or two at his rear molars. He was a tightwad. I only saw him go into his wallet twice, and both times he turned his back on me so that I couldn’t see how much money or whatever he had in his billfold. He had no fat on him whatsoever. He was all lean. He didn’t go out each day armed to the teeth with rifles and knives and stuff. He went alone, usually with only a pistol on his belt. It was almost as if his body was his weapon… maybe thinking that he would take a gun from someone else if it was needed and use it to kill. He had high energy. He ate, often alone, with great relish. He walked fast. He was always doing something, and when that something was to wait for a helicopter or whatever, he’d hunker down and read a book.

Ah, and those books he read. Following is a description of Kayak, my roommate at Long Tieng, taken from my Codename Mule book. He and I were going up to Bouam Long one day:

“Waiting was part of the job, and all the officers carried paperback books. Most would read a couple of books a week—fiction, nonfiction, the classics. Except Kayak. He read the thickest, dullest tomes ever written, mostly about economics and the stock market, but also books with such titles as Calculus as Art and Labor Union Considerations of Dental Plans. Financial journals and curious articles such as “The Effects of the Industrial Revolution on Italian Emigration Patterns.” Greek (another CIA case officer) pulled Kayak’s book out of his hands as we walked into Air Ops and told him that he was crazy. Either he was crazy for reading stuff like this or this stuff made him crazy, one or the other. Kayak, sitting on the floor, leaning against the back wall with his knees up, reached up, took the book from Greek, and went back to reading without comment as he swirled his toothbrush from side to side in his mouth.”

Or later in the book this:

“Kayak, the loner, usually slipped away from the headquarters bunker when business was over and went to our room. He had no interest in small talk. He took a bath before going to bed, naked, and read late into the night.”

I usually went to my room before midnight. Kayak, awake, reading, stayed in one position on his bed for only five minutes at a time and then flipped into a new position as he hit the pillow with his fist to get it readjusted. He also ate crackers, constantly, like a rat — gnawing away, taking small bites, for hours on end. The incredibly dull books he read tended to be heavy, and he manhandled them from his chest to his pillow, where they made a whoosh sound as they hit the bed clothing. The area around his bed was littered with big books. I never did know where he got them.

I often thought the Sky case officers at Long Tieng were uniquely suited to the job: by experience, temperament, and personality. All were men of accomplishment, self-starters, with years of combat experience. Some were suspicious about Stateside society and uncomfortable with the social revolution of the Sixties. Certain Sky behavior could have been looked on as anti-social. Were we this way before we arrived, or did we develop suspicious attitudes because it was part of the culture? Why did we love this godforsaken place, the stone-age Hmong and the rowdy Thai mercenaries? We were a closed society of little more than a dozen men. We were clannish. We were all so different, yet we had become so similar.

Why, though, didn’t Kayak wear any clothes to bed? I asked around one time—everybody but Kayak slept in their shorts. Lying there across the room, reading those dull books, eating crackers like a rat, hitting that pillow every five minutes, naked—he was on the other end of the spectrum from the girl singers of the world. I just wish he’d wear shorts. Why did he walk around with a toothbrush in his mouth during the day? Why was he so restless, always anxious to get out there in the thick of the action?

The Air America pilots, who did not understand this man, said he had a death wish. I lived with him, but I didn’t understand him either. Who gave him all those crackers?

Most who knew him would agree with Air America that the dominant thing about Kayak was his lack of fear and his interest in seeking out danger. I was on the battlefield of Southeast Asia for five of the 10 years the U.S. was involved there, and I saw no one else as keen for combat as Kayak. He would tell you, if you asked, that he really hated the communists; but I don’t think that explained his constant interest in mixing it up. It was just part of his DNA. He was a natural born killer.

Also in the way of traits, he did not care what you thought about him, or his crackers. Most of us growing up wanted to be accepted and were sensitive to peer pressure. Kayak missed that lesson on the playground. He didn’t give a flying rabbit what you thought of him.

Also of note is that Kayak was absolutely sincere, absolute serious, in what he did. He didn’t develop his reading habits to impress others. He didn’t try to impress with his smarts, people just knew. He didn’t do a lot of socializing… but he certainly wasn’t anti-social… he just didn’t care for chit-chat. He and I were friends and we never had a personal conversation that I can remember. It was all here-and-now stuff.

It is also interesting to note that as much as he liked to take risks—as unusually good as he was at that—he was grounded as a personality. He was comfortable in his own skin, as unique as he was.

A thinking man’s risk taker

He had good judgment. Otherwise he might have appeared to be just an eccentric wild man. The extensive testing he did coming into the CIA must have uncovered his capacity for good judgment, which made him hireable by an organization that was particular about the people it hired. Take this story, for example.

On a weekend off during initial training, Kayak and a friend were in Washington en-route to a party of some kind when it was decided that they needed to get a bottle of booze, so the friend who was driving pulled into a no-park zone near a liquor store. Kayak sprinted to the store to do the shopping. The friend waited and waited, with his eye on the entrance. No Kayak. He saw at least one other guy go into the store and come back out again. Still no Kayak.

Finally Kayak came out with a bottle in a brown paper bag and got into the car. As they merged back into traffic, the friend asked what had taken him so long.

Kayak said some guy came in and robbed the place. He was standing by the cash register when the robber approached, pulled a gun and demanded all the store owner’s money. Asked why he didn’t do anything, Kayak said there were other people in the store, and besides, if he took the guy out, there would be police reports and stuff, and they’d miss the party. It was just money anyway, he said.

I know Kayak lived for a situation like this, but he let common sense prevail. With Kayak that wasn’t an enigma. He was a thinking man’s risk taker.

There are plenty of stories about this unique guy. He quit the agency after Laos and, as a private mercenary, was eventually killed by Cubans on the Angola border in Africa. His body has never been recovered.

James E. Parker spent 34 years with the CIA, and was an Infantry platoon leader in Vietnam.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers