by Susan Katz Keating

Yes or no; Да или нет? Did a Russian assassination team inflict the mysterious Havana Syndrome on American targets, as reputable journalists allege; or has an innocent unit been framed, as Moscow would have us believe? To anyone looking for answers, here is one Red flag to consider. It comes in the form of a decades-long Soviet offensive that the Kremlin put back on the radar when talking about Havana Syndrome. The flag to consider? Moscow has done this before.

“Nothing New”

Havana Syndrome first came to public attention in 2016, when American security officials stationed in Havana, Cuba, reported alarming symptoms. The officials fell ill with debilitating headaches, extreme vertigo, intense ringing in the ears, visual disturbances, and other frightening effects.

Over the years, hundreds of American officials and their families reported the symptoms in locations around the world, including Washington, D.C.

One CIA operations officer, Marc Polymeropoulos, felt them during a 2017 work trip to Moscow. He recounted the experience in an essay this year for The Insider.

“I could not get up without falling to the floor,” wrote Polymeropoulos, who retired from the CIA in 2019. “I felt like I was going to throw up and pass out at the same time. It was terrifying, and I was in serious distress.”

The syndrome officially is a puzzle, with some naysayers claiming that it doesn’t exist, or that people who report it actually are suffering from mass hysteria or panic attacks.

The sufferers know otherwise – and serious journalists, myself included, believe them.

In early April of this year, three journalistic heavyweights – The Insider, 60 Minutes, and Der Spiegel – released the results of their joint investigation into Havana Syndrome. They made a strong case connecting it with a Russian GRU hit squad, Unit 29155.

READ MORE from Susan Katz Keating: What Is the Russian Hit Squad Linked to Havana Syndrome?

The Kremlin immediately objected.

“This is nothing more than a groundless accusation by the media,” said Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov.

While denouncing the findings, though, he inadvertently unfurled a red flag.

“This is not a new issue, it’s been talked about in the press for years,” Peskov told reporters on April 1.

Peskov more accurately could have said “decades,” stretching back to the Cold War. That’s when the Soviet Union bombarded the U.S. Embassy in Moscow with steady pulses of microwaves.

Manezhnaya Square, Moscow, 1941. The U.S. Embassy is on the left. The building on the right is the Moscow Hotel. (U.S. National Archives)

One former foreign service officer, James Schumaker, immediately drew the connection when he learned about Havana Syndrome.

“It was Moscow Signal all over again,” Schumaker wrote in an essay for The Foreign Service Journal.

The “Moscow Signal”

The “signal” has a strange and convoluted origin story. It stems from 1945, when a group of Soviet children gave a gift to U.S. Ambassador W. Averell Harriman. The gift was a large wooden replica of the Great Seal of the United States. The ambassador hung it in the library at Spaso House, the U.S. residence in Moscow. The gift contained a secret listening device, activated by radio waves.

The transmitter worked well for six years. One day in 1951, a British radio operator was shocked to hear the British Air Attaché’s voice on an open Soviet Air Force radio channel. The following year, an American radio operator overheard a conversation that seemed to be based inside Spaso House.

Investigators traced the transmission to a bug inside the Great Seal. When technicians disabled the listening device, the Soviets regrouped. They began bombarding the U.S. embassy with microwaves – the “Moscow Signal.”

The library at Spaso House.

Why did Moscow sent the microwaves? There are several theories. Among them is that the Soviets were trying to jam American frequencies. Another was that they hoped to exert mind control over their human targets.

The international tension surrounding the signal is shown in a series of documents in the U.S. National Archives, and that were compiled by George Washington University.

As shown in the documents, the Nixon Administration in 1969 was concerned about “personal medical problems being linked to signal,” and wanted the Soviets to stop sending it. The administration had little faith that Moscow would cooperate.

In a cable to the ambassador, Under Secretary of State Elliot Richardson wrote: “It appears highly doubtful Soviets intend to give us any satisfaction in this matter.”

He was right. Moscow kept sending the signal.

Unlike with Havana Syndrome, when targets felt immediate symptoms, the Cold War microwaves didn’t knock anyone to the floor with vertigo, nausea, and headaches. American researchers tried to replicate the radiation levels on monkeys, and reported no ill effects. The Moscow Signal seemed puzzling but physically harmless.

Still, it was unsettling.

When Secretary of State Henry Kissinger prepared to visit Moscow in 1975, he telephoned the Soviet Ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin.

“I want to talk to you about the signal,” Kissinger said. “That beam you are beaming into our Embassy in Moscow… Maybe you could turn it off until I get there.”

The two diplomats chatted and joked, with Kissinger saying that the Soviets “could give me a radiation treatment.” In a more serious vein, Kissinger noted that the issue could become a major problem.

“We really are sitting on it here but too many people know about it,” Kissinger told Dobrynin. “We will catch hell unless we can say something is happening” to stop it.

The State Department in July 1975 gave U.S. Embassy staff members a “Fact Sheet” to show their doctors when seeking medical treatment connected to the microwaves. It seemed like a pro forma effort, since no one complained of unusual health problems.

Then people fell ill.

Life in the Big City

Walter Stoessel, who was U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1974-1976, developed strange symptoms. He was nauseous and anemic. He started bleeding from his eyes.

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told Stoessel in January 1976 that the notion of the microwaves causing health problems was an “imaginary issue.”

Red Square in Moscow. U.S. State Department photo.

The U.S. press wrote otherwise. The Boston Globe reported that Stoessel was suffering from a blood malady linked to the signal.

In a familiar sounding response, the State Department denied it.

“The American Embassy today termed ‘inaccurate and misleading’ a published report that Ambassador Stoessel had a mysterious blood ailment possibly caused or aggravated by high levels of Soviet microwaves beamed at the embassy,” the Associated Press reported in February 1976.

The news agency quoted a State Department spokesman giving a rhetorical thumbs up about Stoessel: he “feels fine, keeps a busy schedule, leads an active life. has not undergone medical treatment and is not at the present time undergoing medical treatment.”

The Soviet government newspaper, Izvestia, acknowledged that radiation was present outside the embassy. But, the paper said, it was due to life in the big city, where t.v. and radio stations emit signals. Much like Peskov pointed a finger at the media for stirring things up about Havana Syndrome, the Soviet newspaper blamed the bleeding-eyes stories on people who wanted to disrupt relations between the U.S. and the USSR.

The State Department took precautions, though. It installed metal screens around the embassy; “the original tin foil hats,” one diplomat told Soldier of Fortune.

Later that year, The New Yorker published a column saying that two recent American ambassadors to Moscow (Llewellyn Thompson and Charles Bohlen) died of cancer, and that Stoessel had a serious blood disorder.

The microwaves ramped up.

The embassy reported on October 4, 1977, that levels were “higher than any we have measured for more than one year.”

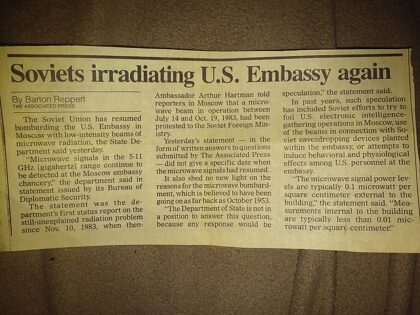

The State Department in the mid-1980’s said that the Soviets had resumed bombarding the embassy after a lull. An article by the Associated Press referenced speculation about health effects, but offered no specifics.

James Schumaker, the former foreign service officer, developed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) after serving in Moscow.

Spurred by reports of Havana Syndrome, Schumaker described his experience at length in an article for the Foreign Service Journal.

“As I followed the Havana syndrome story, it increasingly occurred to me that I had seen something like this before,” Schumaker wrote.

“It was Moscow Signal all over again,” he noted, adding, “It is a puzzle to which there is still no answer.”

Some of the puzzle pieces are heartbreaking to handle. Those are the ones involving radiation and ill health. Others are infuriating. Those are the pieces involving denial and avoidance.

“It’s betrayal, pure and simple,” the foreign service officer told Soldier of Fortune. “I guess that’s the current version of, life in the big city. Suck it up, kid; no one cares.”

Doubling Down

In March 2023, the Pentagon’s Inspector General issued a report on its investigation into how the Defense Department handled complaints about Havana Syndrome, or, “Anomalous Health Incidents” [AHI]. The report is nearly impossible to decipher.

Among its findings: “the DoD’s AHI Cross‑Functional Team lacks the authority to fully execute the DoD’s response to AHI.”

“What the hell does that mean? It’s just gobbledegook,” the foreign service officer said. “It allows them to keep pretending they don’t know what’s going on.”

The White House, the Pentagon and the State Department on April 1 doubled down on their stance that it is “very unlikely” that Havana Syndrome was caused by enemy operatives.

Russia continues to scoff at the notion that it was involved.

This, despite the reports from The Insider, 60 Minutes, and Der Spiegel. The reports are based on travel documents, mobile phone records, eyewitness testimony, and interviews with U.S. officials and victims. Their investigation tied reports of Havana Syndrome with the presence of members of Unit 29155 of Russia’s military intelligence service, known for sabotage and assassinations. The journalists also found that members of GRU Unit 29155 received awards and promotions for their endeavors with energy weapons.

The weapons work.

“I speak on a daily basis with the victims,” Polymeropoulos wrote. “It is tragic to hear their stories of illness, anxiety, depression, sadness, and betrayal.”

The syndrome is “the Agent Orange, Gulf War Syndrome, and Burn Pits of our time,” he wrote. “These other incidents of mysterious health issues — which were also at first denied by the U.S. government — turned out to be both real and terribly harmful to Americans who were serving their country.”

I’m pleased to announce that the new head of our Health Incidents Response Task Force, Ambassador Moore, and our recently appointed Senior Care Coordinator, Ambassador Uyehara, will build upon our existing efforts and lead the charge to tackle these Anomalous Health Incidents. pic.twitter.com/VetwRiaZBS

— Secretary Antony Blinken (@SecBlinken) November 5, 2021

The State Department says it will care for people who are suffering from “possible AHI,” and has vowed to “investigate the cause behind these reported injuries.”

Still there remains the bright red flag of the Moscow Signal – and the sobering outcomes.

“Death, denial, and gobbledegook,” the foreign service officer said. “Is that the best we can expect?”

In 1986, Walter Stoessel died of leukemia. He was 66 years old.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor in chief at Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers