by Susan Katz Keating

In retrospect, it seems fitting that I met Viktor Belenko in Reno. He was a gambler hanging out in a gambling town, surrounded by pilots in their fast moving aircraft, barreling wildly around pylons. I went there many years back, looking for stories to be found at the annual Reno Air Races. While squadrons of old biplanes, T-6s, P-51s and more buzzed along the flight line, I walked around a corner in back of a hangar, and stopped suddenly in my tracks. There before me sat the legendary Soviet MiG pilot, Viktor Belenko.

“Hi,” he said from behind a table stacked with books about his escapades. “You want autograph?”

I sat down to chat.

As we talked about airplanes and aviation hijinks, our conversation turned to Belenko himself. He assured me that his daredevil Cold War escape from the Soviet Union was as dramatic as I’d heard. He was right. But he couldn’t say that now. These days, fewer people remember him, let alone the details surrounding his wild flight to freedom.

Escape via Foxbat

Belenko had been a respected pilot with the Soviet Air Defence Forces. But by 1976, he wanted to leave the Soviet Union. At the time, he was based near Vladivostok, as part of the 513th Fighter Regiment, 11th Air Army. The unit lived at Chuguyevka Airbase. It’s worth noting that the Soviet Air Defence Forces were a separate aerial branch from the Soviet Air Force, and that its members were an elite and trusted band. As such, Belenko, too, would be trusted. So much so, that when his blood pressure was elevated on the morning he planned to escape, the flight surgeon believed Belenko when he said he wasn’t nervous about anything, and that his BP was up because he’d been exercising.

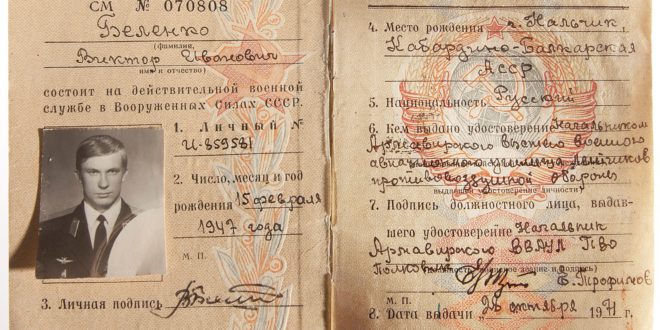

Lieutenant Viktor Ivanovich Belenko at the time was learning to fly the new Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25 supersonic interceptor jet. Western analysts had not yet examined a real “Foxbat,” and considered it to be a highly capable threat to NATO aircraft. The Secretary of the Air Force, Robert Seamans, had said the MiG-25 was “probably the best interceptor in production in the world today.”

The 29 year old Belenko correctly assumed that the United States would want to obtain a Foxbat.

Belenko planned to deliver one in person, in exchange for asylum. The jet was a voracious consumer of fuel, though, and wouldn’t make it from Chuguyevka to a U.S. or Canadian air base. It could, however, in theory reach a support base in Japan. Maybe.

Belenko set his escape for Sept. 6, 1976, when he would have good weather.

“If the weather held, his chances of reaching the objective would be as good as he ever could expect,” author John Barron wrote in his book about Belenko, MiG Pilot.

The mission contained extra elements, Belenko told me. The squadron that day would fire rockets; so, too, would a group of MiG-23s from other bases. They could easily shoot him down. Another factor to consider was that clouds were starting to move in around Japan.

The escape would be a gamble, but Belenko went for it.

“Why not,” he told me with a grin. “One way or another, it was my lucky day.” He laughed to make sure I understood what type of luck he expected. “Good. Bad. Is all part of the luckiness picture.”

The day of the breakout, Belenko climbed into his cockpit. He activated various switches – but not the radar switch. On the ground, the radar impulses were so powerful they could kill rabbits in a nearby field, Belenko told me.

He took off into a perfect, cloudless day. He slipped into formation with his squadron. He flew a typical circuit. At the far edge of the route, though, he didn’t circle back around according to the flight plan. Instead, he kept going. He allowed the plane to descend gradually to 19,000 feet. There, he suddenly threw the Foxbat into a steep dive that plunged him to 100 feet. He barrelled along at that altitude, where he wouldn’t be spotted on radar.

The other pilots in his squadron chased after him, but Belenko had a good lead. He flew low and fast, at one point pulling up to avoid being hit by waves. He approached Japanese air space.

Then began a series of pop-ups and descents, wherein Belenko made himself known to Japanese radar, and dipped down again to avoid being shot from the sky. The Foxbat of course guzzled fuel at a prodigious rate.

The jet ran perilously low on gas.

“I had almost nothing left,” Belenko told me. He said it casually, as if he were describing a bag of popcorn, or a can of beer. But the message was clear: the engines soon would sputter to a halt, and the plane would crash.

Miraculously, Belenko spotted an airfield – with a civilian 727 jet liner heading directly toward him.

Baron described in his book what happened next.

He jerked the MiG into the tightest turn of which it was capable, allowed the 727 to clear, dived at a dangerously sharp angle, and touched the runway at 220 knots. As he deployed the drag chute and repeatedly slammed down the brake pedal, the MiG bucked, bridled, and vibrated, as if it were going to come apart. Tires burning, it screeched and skidded down the runway, slowing but not stopping. It ran off the north end of the field, knocked down a pole, plowed over a second and finally stopped a few feet from a large antenna 800 feet off the runway. The front tire had blown, but that was all.

Belenko told me that when he landed, only 30 more seconds worth of fuel remained in the tank.

“I want to defect”

With the plane at rest in Japan, Belenko climbed out onto the wing. He fired a pistol into the air, and waited for officials to approach. When they did, Belenko announced that he wanted to defect.

There came a flurry of diplomatic activity. The Soviet Union claimed that Belenko had been drugged, and demanded that he be returned. Japan refused. Moscow alternately begged, cajoled, and threatened Belenko. He asked for asylum. The U.S. government granted it.

“It was a very busy time,” Belenko told me. But also a happy one. He was brought to the United States, and soon was made a U.S. citizen.

In those days, Belenko was famous. He settled in, made friends, and found a good job.

And what of the Foxbat?

Japan held onto the plane long enough for U.S. experts to examine it in great detail. They found that the jet was not as fearsome as they had believed.

The aircraft was taken apart and shipped back to the Soviet Union. The government of Japan sent Moscow a bill for $40,000, to cover shipping, along with damage to the airport runway. Moscow in turn asked for $10 million, to cover losses. According to reports, neither side paid the other.

That day when Belenko and I met at the Reno Air Races, he was jovial, happy, and full of jokes. I asked him if he was glad he defected.

“Of course!” he grinned. “I have a good life here in our country, the United States of America.”

We sat watching the race planes whiz through the sky. The pilots pulled tight corners, rounding far pylons as they flew the course, battling to outrun one another. Even from the ground, it was thrilling.

I asked Belenko if he planned to do any gambling while he was in Reno.

“I should,” he laughed. He waved at the lead plane, urging him onward. “I am the luckiest man alive!”

Update: Viktor Belenko quietly passed away on September 24, 2023, following a brief illness. His sons Tom and Paul were at his side.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers