by Susan Katz Keating

Why did Soviet forces abandon Afghanistan in 1989 after nearly 10 years of war? Western analysts have burned through terabytes trying to explain it. What else besides the fierce Mujahideen drove the Red Army to retreat with nothing to show but shattered pride? Some credit the CIA-supplied Stingers and French MILAN anti-tank missiles. Others point to economic factors inside the USSR. But few talk about the four-legged Americans who moved through the mountains like smugglers with a vendetta, hauling the war on their backs, one surefooted step at a time. In other words, the mules.

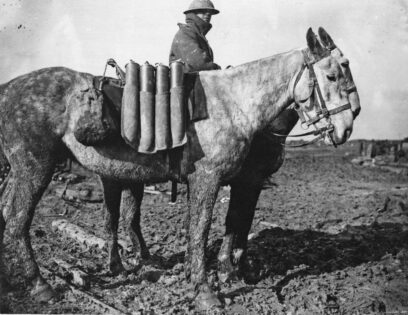

These long-eared, iron-lunged beasts — the bastard offspring of a jackass and a mare — were not simply beasts of burden. They were the logistical lifeline of the Afghan resistance. With greater staying power than a billion-dollar procurement contract, mules carried ammo, munitions, rockets, and more across rugged terrain that drove Soviet quartermasters to rethink their life choices.

Mule Husbandry 101

If you’ve never had the pleasure of meeting a mule, the creature is a mix between a male donkey (a jackass) and a female horse (a mare). The result is a tough, hardworking animal that can’t reproduce. Flip the combo—put a stallion with a female donkey (a jenny)—and you get a hinny. Hinnies also are sterile. They’re smaller, weaker, and not as good-looking as mules, so people don’t usually breed them on purpose.

The donkey fathers give mules their loud bray, their toughness, and stamina. The horse mothers impart strength, size, and the ability to pull a load. Thanks to all this genetic mixing, mules are able to go places horses wouldn’t dare. They’re smarter than horses, too. So if a mule senses something’s not safe, no amount of yelling, kicking, or carrot-dangling from the handler is going to change its mind.

Mules also are calmer and more reliable under pressure—like when things start blowing up around them.

Hoofbeats on the Mountain

In the 1970’s, after a series of coups, uprisings, purges, and mass executions, an iron-fisted regime took power in Afghanistan. The Bolshevik-inspired government was so brutal, Soviet diplomats warned that it would provoke armed rebellion – which it did. An uprising spread throughout the country. In the mountains, guerrillas used mules to move weapons and supplies through the harsh terrain.

In 1979, Soviet forces arrived to support the regime against the rebellion. The native Afghan mules remained on the job, and their workload increased. The mules took a beating. They were either worked to death or blown apart. China offered replacements, but at black-market prices only a drug lord could love. Turkey and Egypt sent a couple herds, but the beasts were small. The limited pool of suitable animals soon dried up.

The hoofbeats died away, and the brays fell silent.

Enter the CIA.

How the American Mule Got Drafted

As U.S. analysts searched for ways to bolster the Mujahidin insurgents, the CIA dusted off an old idea and sharpened it for guerrilla war. Someone at Langley remembered that mules had served in the U.S. Army in Korea. Those mules had been put out to pasture, where the forgotten veterans grazed in peace until the last one crossed the great Rainbow Bridge without being able to impart even genetic memory to non-existent offspring. Their storied history evaporated like trail dust off a pack mule’s haunches.

But in the summer of 1987, the CIA launched a reprisal. A plan took hold. Bring back the mules. American mules. The kind that could haul 200 pounds of gear over terrain that would snap a tank tread to bits. No engine. No radar. Just hooves, muscle, and a mission.

Word went out. The federal government wanted prime pack mules, saddle-broken and willing to tolerate a lead rope in exchange for some prime oats and quality alfalfa. The government was offering between $500 and $1,300 per head, for animals aged 3 to 8, combat-capable, and preferably bilingual. Breeders who hadn’t seen a government buyer since the Truman administration found themselves talking to Uncle Sam.

The government acquired its livestock, and the plan proceeded.

Operation Mulelift

The first mule transports lifted off from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in September 1987. Specially configured 747s from the Flying Tigers cargo line hauled 114 animals per 22-hour flight — pressurized to go easy on their ears, cinched down, and headed for Pakistan. Nearly 2,000 American mules eventually were airlifted, and not a single one complained about legroom.

Upon arrival, the mules were enrolled in what could only be described as CIA-run basic training. They met their new handlers, learned the rhythms of Pashto, and got acquainted with the sound of boom and the smell of cordite. The human muleskinners formed a tight bond with their charges.

The Silent Infiltrators

Before you could say Khyber Pass, these mules became integrated with the resistance. They hauled Stingers and MILAN missiles up goat trails where no helicopter could hover and no tank could crawl. They carried mortar tubes, ammunition, spare barrels, and more. After delivering the goods, they carried wounded fighters back down the same treacherous paths. They didn’t spook, didn’t complain, didn’t quit.

Soviet soldiers encountered valleys filled with braying shadows. Helicopter pilots met missiles over land where none had previously launched. Chaos followed.

Logistics win wars, and the mule — not the microchip — was the unsung hero of this campaign.

Within months of the mules being introduced to “the Graveyard of Empires,” the Soviets pulled their troops out of Afghanistan. The soldiers walked out, or rode on mechanical transport. Not one mule volunteered to carry them.

Representative Charlie Wilson, the Texas congressman immortalized for bankrolling the Afghan resistance, called the mules “absolutely vital.” Not sexy, not strategic — but vital.

History’s Hoofprints

Mules have a long, dusty pedigree in warfare. The Carthanginian general Hannibal led them over the Alps with his army and elephants in 218 BC. Elsewhere, mules carried British packs across Boer country, and American supplies through the trenches of World War I. They slogged through Italy and Burma in World War II. The U.S. Army once fielded entire mule-drawn artillery units.

In sum, mules repeatedly have proved their worth in situations too dicey for men and machines.

The truth was learned too late by the Red Army. Even now, denial crops up. Colonel-General Boris Gromov, the last Soviet commander in Afghanistan, swears that his Army there was never beaten.

“There were no tasks that the 40th Army could not accomplish,” Gromov told TASS last year. “It was a very powerful army. There can be no question of any defeat.”

We have to break it to Gen. Gromov. The fact remains that the American mule — sterile, stubborn, and smarter than most lieutenants — impressed its tracks deeply all over Red Army pride. When Gromov’s men retreated over the Hairatan Bridge into Soviet Uzbekistan, the last thing they heard was a chorus of mules, braying with derision.

(U.S. Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Apollo Wilson)

Today, mules serve with distinction in the U.S. military. At any given training cycle, you can find them at various Animal Handler and Packers courses. They work in austere terrain, slogging through shallow waters and stepping across fallen trees. Draped in camouflage, they scale mud-covered mountains where a quick head-lurch can bring a mouthful of foliage to savor in defiance of the regs.

Modern handlers say they strive to show these equine charges the ropes. More likely, it’s the other way around.

Mules that work with humans are not obedient. They allow themselves to be handled, like they’re giving a favor. Today as in years gone by, the modern Military Working Mule proceeds with the slow, deliberate steps of a beast who’s seen enough miles to know when to walk and when to dig in.

And when to mule-kick the enemy.

With a tip of the Red Beret to Austin Lee of Galilhub for flagging this mule train of a story!

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers