by Susan Katz Keating

“I lie awake at night, filled with regret. I deeply regret that my bombs didn’t kill more people.”

That’s what the so-called “Terror Priest,” Father Patrick Ryan, told me when I asked what he wanted people to know about him. A fierce Irish nationalist, he was a one-man guerrilla force who resisted Irish Republican Army leaders as much as he helped them. He enabled the IRA to launch audacious attacks against British interests, but also deceived the IRA, and faced off against their powerful and much feared chiefs of staff. I sought out Ryan years ago in Ireland, as a journalist looking for insights. Working through intermediaries, I gave him my agenda: I didn’t aim to exonerate him, and I wasn’t there to judge. I wanted to understand the mind of an intensely driven man, who put the cause above all else, and whose reach extended into Libya, Spain, Colombia, and elsewhere. I wanted to capture his thoughts before they vanished into smoke and memory. To my surprise, he agreed to talk.

Ryan in an interview with the BBC. Video screenshot.

Ryan died this summer at age 95, after decades playing cat-and-mouse with authorities while funneling weapons and cash to the Provisional IRA. When I first interviewed him, my colleagues warned me that Ryan was dangerous, and I was being reckless. But I knew his world well. I understood that he was no threat to me, nor I to him. So I stepped back into that world, notebook in hand. When I learned of his death, I dug out the pages, and revisited the man the British called the “Devil’s Disciple.”

Patrick Ryan was a Roman Catholic priest, an arms smuggler, and a key conduit between the Provos and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. He was gun lord to an IRA hit squad in Belgium, and was accused of orchestrating assassinations across Europe. But when Ryan talked to me, he zeroed in on his true legacy: the bombs.

When speaking about them, he had a cold, bloodless demeanor, like a shark explaining how its teeth enabled it to consume live prey.

“My design brought order to chaos,” Ryan said evenly, in his gentle Tipperary accent. “It changed everything.”

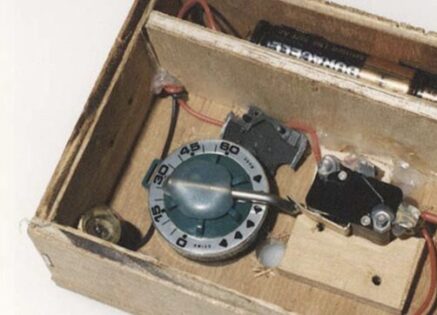

The design was a component for bombs. It was based on the Swiss-made Memo Park Timer, a coin-sized windup device that looked like a cross between a kitchen timer and a compass. It was a keychain gadget, meant to remind drivers how much time they had left on their parking meters. Ryan transformed it into a switch that became the PIRA’s calling card in scores of explosions.

“It was very simple,” Ryan said. “When the clock ran out, time was up.”

Portions of a TPU kit with a Memo Park Timer, designed by Patrick Ryan.

I knew what that meant for those whose time was up on the receiving end. For 38 British soldiers in Warrenpoint, Northern Ireland, in 1979. For Lord Mountbatten and family off the coast of Sligo, Ireland, in 1979. For the four men and seven horses of the British Army Household Cavalry parade in Hyde Park, London, in 1982. For 11 soldiers and bandsmen at Regents Park, London, 1982. For British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet in Brighton, England, in 1984. And so many more.

One Belfast shopkeeper who lost his leg in a 1979 blast told reporters: “The bombs didn’t just blow up bricks. They blew up lives. We never knew if we’d come home at night.”

The effects linger. A retired officer from the Royal Ulster Constabulary recently told me: “In quiet moments, I still smell the blood. I still hear the screams.”

What, though, did these bombs do for the Provos? How did this level of destruction and violence help the cause of Irish nationalism?

“It made chaos answer to us,” Ryan said. “It allowed us to direct the storm.”

The Storm

The storm had a long history of shattering its own forecast. During the “Dynamite Wars” in the 1880’s against Britain, Irish bombs wreaked havoc – but sometimes killed their own handlers. During the IRA campaign against British rule over Ireland in 1919, guerrillas in Cork moved their 262 bombs, along with sticks of gelignite, detonators, and bottles of acid from under the floorboards of their room – and in the process, blew up their entire tenement house.

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, explosive devices frequently created what the IRA called “own goals,” killing those who made or emplaced the bombs. In 1971 alone, 31 members of the IRA died when their bombs went off ahead of schedule. In 1972, another 17.

“It was appalling,” Ryan told me. “Shameful.”

What part was appalling, I asked.

“They were not consistent,” he said, like a priest assessing his wayward parishioners. “They made mistakes, like not scraping the paint off a drawing pin.”

He was referring to a failed effort to blow up an aircraft in 1974. An IRA bomb on a plane from Belfast to London included a metal pin affixed to an analog watch. The pin had a thin coating of paint, enough to prevent it from making an electrical connection when the watch hand rotated into place.

What part was shameful, I wanted to know.

“Sloppiness.”

Ryan cited the case of Jack McCabe, a veteran bomb-maker. In 1971, McCabe was working with fertilizer, mixing “blackstuff” in his shed. He stirred the mix with a shovel. The metal shovel scraped the concrete floor, created a spark, and ignited a massive explosion.

“McCabe lived long enough to explain what happened,” Ryan said. “So there was some good that came of it. A lesson.”

At the same time, premature detonations went off in other bomb sheds. Several occurred when the bomb-builders wore their gold wedding rings into the shop. The rings met with static electricity, and triggered explosions.

“Madness,” Ryan said, shaking his head.

British troops in Northern Ireland.

Still, the demand was relentless. The pressure mounted when Provo leaders established quotas. One “engineering” team, for example, was assigned to produce two tons of fertilizer bombs per week. It was a high pace, given the meticulous work that goes into creating such devices.

The fertilizer bombs presented one set of problems for the builders. So, too, did those made from “Magic Marble,” gelignite, petrol, and other substances. Each had peculiarities, but the common element was the timing mechanisms.

“It was unreliable,” Ryan said. “The engineering department looked for solutions.”

Among them: Condoms.

“Rubbers were converted into timers,” Ryan said. The method was to insert one inside another, fill the “balloon” with sulfuric acid, and place it above a reactive substance. The acid eventually would eat through the layers, dripping acid onto another substance, to ignite the charge.

The design was both dangerous and challenging. In the southern Republic of Ireland, condoms were illegal. Engineers in the Republic had to cross into British-owned Northern Ireland in order to buy them – a risky endeavor when obtaining materials, no matter how mundane they might seem.

“Rubbers were against the law. And they were immoral,” Ryan said.

I pointed out that gunrunning and bomb-making also were illegal, and that killing was a Mortal Sin in the Catholic Church. He quickly chided me.

“That is a clumsy interpretation of Canon Law,” he said.

I didn’t argue with him – it doesn’t pay to debate Church law with a priest. But I asked how he reconciled his avocation with his actions.

“My order, the Pallotine, supports prisoners and those in need,” he said calmly. “I fulfilled that mission.”

His view of pastoral duty included activities that reshaped his role in the conflict. Activities that began in Tripoli.

Libya

When Colonel Muammar Gaddafi seized power in Libya in 1969, he used his country’s oil riches to support revolutionary movements around the world. Among them, the IRA. He gave them money, weapons, and Semtex, the Czech-made plastic explosive. Ryan became the conduit.

Ryan moved to Europe. There, he handled the Libyan money, and established his own protocols for dispensing it to the Provos. By then he increasingly was at odds with IRA commanders, and accused them of being compromised. He kept secrets, and refused to provide the full details on major smuggling operations.

When a large sum of Libyan money mysteriously vanished en route to the Provos, Ryan clamped down to control the cash. This enraged the IRA Chief of Staff, Seamus Twomey, who told his Army Council: “Who the fuck does he think he is?”

How do you respond to that, I asked Ryan.

“I know fuck-well who I am,” he said. “An Irish nationalist.”

Bomb blast in Northern Ireland

The Irish nationalist spent more time in Tripoli, where he posed as a rep for the Irish beef industry. He grew closer to Libyan intelligence. In Europe, meanwhile, he was suspected of orchestrating IRA hits against British targets who were stationed there. He remained on the move, knowing he was being watched.

Innovation

Through it all, Ryan agonized over the bomb teams in Ireland.

“Their devices were not reliable,” he said. “It was getting them killed.”

Amid the agonizing, Ryan drove to Geneva in 1975, to deposit Libyan cash in a secure Swiss bank account. By chance, he walked past a clock shop. He spotted the Memo Park Timers in the window.

“It was like the clouds opened up and the shaft of light came down,” Ryan said. “There in the window was a display of these little timers.”

He thought they could be turned into components for bombs. He bought several. He reworked them to see if his idea would work. It did. He returned to the shop, and bought hundreds.

I will not provide details on how the re-engineered devices worked, but open source materials show that they were incorporated into systems known as Time-and-Power-Unit (TPU) kits. The kits enabled the Provos to train new bomb-makers faster, and allowed them to plant bombs, arm them, and leave the scene for up to months in advance.

Soon, Memo Park guts were the IRA’s calling card, wired into scores of explosions. The British EOD units, the “Felix” squads, learned to look for the TPU kits after a blast.

“It helped us determine who built them,” one former Felix told me. “No one else was using them.”

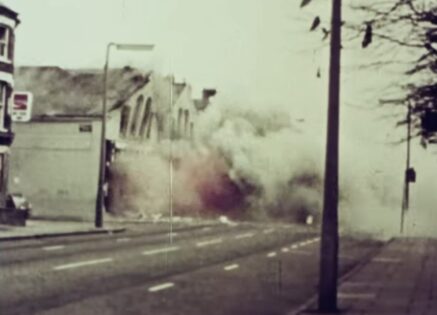

The Brighton Hotel, where the IRA tried to kill Margaret Thatcher, using Ryan’s design.

The IRA, for its part, didn’t care about clues in the wreckage – it eagerly claimed credit for the attacks. After the group tried and failed to kill Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet, the IRA issued a statement:

“We have only to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always.”

Ryan didn’t flinch when telling me how he felt about his role.

“I am proud of what I did,” he said.

He told Irish and British news outlets the same thing. When the BBC asked him in 2019 if he had any regrets, he was unequivocal.

“Oh, I have big regrets,” Ryan said. “I regret that I wasn’t even more effective, oh yes. Absolutely. I’d like to have been much more effective than I actually was. But we didn’t do too badly.”

Aftershocks

Beneath the calm demeanor, Ryan led a tumultuous life. He was kicked out of the priesthood, arrested in Belgium, and charged with terrorism. He went on a successful hunger strike to avoid being extradited to the UK, and had a bitter falling out with another IRA Chief of Staff.

When I met with Ryan, I spotted the nearest thing he had to a chink in his armor, a small glimpse of sentiment. He carried with him a talisman: an original, keychain version of the Memo Park Timer. The gadget that helped cement the IRA’s standing as the most prolific bomb makers in guerrilla history, with an engineering department unmatched by any non-state actor.

Father Ryan lived long enough to evade prosecution, to see the Troubles recede from the headlines, and to live out his days as a free man in his beloved Ireland. He never saw the island united; it remains partitioned to this day. But he remained resolute.

“I take great satisfaction from what I accomplished,” he told me.

Patrick Ryan died at peace with his legacy.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor in chief at Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers