“Death to Tyrants”

By Dr. Martin Brass

From the September 2007 issue of SOF

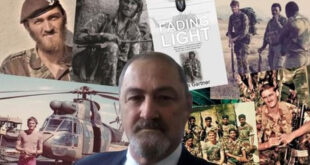

SOF publisher, Lt. Col. USAR, (Ret) Robert K. Brown, who had fought the Communist aggressors during the Vietnam War, and his wild, colorful assortment of combat journalists, dubbed the SOF ‘Wild Bunch’ trotted around the globe, camera in one hand, gun in the other.

SOF publisher, Lt. Col. USAR, (Ret) Robert K. Brown, who had fought the Communist aggressors during the Vietnam War, and his wild, colorful assortment of combat journalists, dubbed the SOF ‘Wild Bunch’ trotted around the globe, camera in one hand, gun in the other.

During the 1970s, the SOF Wild Bunch were on the ground, reporting the events of the Rhodesian civil war, the Soviet sponsored war in Afghanistan, the U.S.S.R interference in Lebanon, in Cambodia, in Burma, and a myriad of other global hotspots.

Toward the end of that decade, the Cold War was again, as it had done in the 1960s Cuban Missile Crisis, edged far too close to home, creating a greater sense of geographical urgency than had the Vietnam War. Cuba and Nicaragua had fallen under the control of the Soviet Empire and as SOF saw it, El Salvador was next on the list of “dominoes” to fall, followed by Honduras and Guatemala.

The Legend of The Bearded One

The best known of those fighting the “forces of evil” was Harry Claflin— fearless, rough and rugged. Harry may have had as much impact on the success of the American effort in El Salvador as any single American.

I met many soldiers of fortune during those years, including Brits, French, South Africans and a number of Americans. The least memorable were those who were legends in their own minds, boasting endlessly of their conquests, real or imagined. Some who had served from Rhodesia to South Africa, to Lebanon and beyond spoke matter of factly of their adventures. The most fascinating of all verbalized with their wary, piercing eyes, not saying much. They didn’t have to— they had fought ruthlessly in vicious battles and survived. Many of their opponents had not.

Harry was an American, a former Marine, tall, lean, scraggy, and just plain mean.

He served two tours in Vietnam as a member of the 1st Force Reconnaissance Company. After leaving the Marines, he worked overseas as a private contractor for four years as a weapons consultant for Agency for International Development (AID). He hired on with the U.S. State Department as a security consultant, providing security protection for government VIPs traveling abroad.

He served two tours in Vietnam as a member of the 1st Force Reconnaissance Company. After leaving the Marines, he worked overseas as a private contractor for four years as a weapons consultant for Agency for International Development (AID). He hired on with the U.S. State Department as a security consultant, providing security protection for government VIPs traveling abroad.

At that time, Harry owned and operated Starlight Training Center in Liberal, Missouri, which offered courses in outdoor survival, ranger type operations and parachute ops.

His expertise was a perfect match with El Salvador’s ill equipped Air Force and Army who needed all the help they could get.

“The paratroopers were in effect, El Salvador’s primary special operations, quick reaction force, and a natural attraction to SOF trainers, most of whom have similar military backgrounds,” Harry quickly discovered.

I first met Harry in the mid 1980s in New Orleans when he was on his way back to El Salvador. He wandered absentmindedly in and out of the smoky bars along the decadent, crowded, noisy Bourbon Street at night, the thoughts behind his furrowed brows and piercing brown eyes gearing up for action.

The ferocious, focused way that Harry attacked his lobster with his long sturdy fingers, his figure slightly bent over the table in a dimly lit restaurant on Bourbon Street, sent shivers up my spine.

I figured that he was merely gearing up for the battlefield. At least, I sure hoped he was when he would occasionally clasp his two hands together so tightly that his knuckles turned white, as if they were wrapped around a machine gun. He would absentmindedly pretend to aim at the ground, move his clutched hands from left to right and back, and mutter under his breath, “kill the cockroaches!”

I figured that he was merely gearing up for the battlefield. At least, I sure hoped he was when he would occasionally clasp his two hands together so tightly that his knuckles turned white, as if they were wrapped around a machine gun. He would absentmindedly pretend to aim at the ground, move his clutched hands from left to right and back, and mutter under his breath, “kill the cockroaches!”

Maybe it was the vodka, I told myself, intrigued by the bearded Western style Crusader. He saw the partially eaten lobster on my plate, asked me gruffly if I was finished, grabbed it and attacked it with even more gusto than he had his own clawed feast, by now a pile of mutilated shells.

RKB and I met Harry again in Fort Bragg in 2005, at a reunion of El Salvador vets sponsored by a member of the MILGROUP, which consisted of a team of 55 U.S. advisors at any one time that had been assigned to El Salvador to train the government troops. Harry’s hair and beard were peppered with gray, but I would have recognized him anywhere. You don’t forget Harry. He still carried himself in that erect manner, full of self-confidence. He now had an aura of accomplishment about him, the restlessness subdued. He was a no bull, gripping storyteller.

For three days, RKB and the rugged merc recalled with nostalgia the near decade that he had spent fighting with the Salvadoran army against the guerillas. They were back in the jungle, vividly and fondly remembering every detail as if each had happened that day.

His saga is that of how the war in El salvador was won; that of a dedicated anti-communist Cold Warrior – an untamed American soldier of fortune.

The Smallest Country in Central America Explodes

The Smallest Country in Central America Explodes

The twelve-year civil war in El Salvador was a culmination of five decades of violence riddled with coups and revolutions and government backed death squads that wreaked terror against their opponents.

In 1931, Gen. Maximiliano Hernández Martínez became ruler after a sucessful coup. The government’s oppression of the citizens during his 13 year rule was highlighted by the massacre of peasants (La Matanza) who joined a resistance led by Communist Party chief Farabundo Martí. 30,000 were killed during the battle between Marti’s band and Martinez’s military government.

Oligarchic military dictatorships continued to rule in the coffee rich country until 1979, when a Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG), of military officials and civilian politicans figures overthrew the military dictator General Humberto Romero, head of the conservative Party of National Conciliation.

The U.S. administration of President Carter backed José Napoleón Duarte Fuentes, the exiled conservative political leader of the Christian Democratic Party. Duarte returned in 1980 to El Salvador to head the military regime. The U.S. authorized the largest economic aid package ever granted in the Latin Countries.

Throughout the war, the United States poured nearly $5 billion of economic aid into the country and over $1 billion in military aid. The Salvadoran Air Force was the number one recipient.

Catholic Archbishop Romero had become the most outspoken opponent of the government that continued to deploy ‘death squads’ to assassinate political opponents. Thousands were executed. He urged the soldiers in the strongly Catholic country to defy orders of the political elites and objected to U.S. military aid to the corrupt government.

Catholic leaders in Latin America have traditionally wielded enormous influence.

For instance, it was an El Salvadorian priest, Jose Matias Delgado, who rang the bells of the Iglesia La Merced in a cry for independence from Spain in 1811. Mexico and five Central American countries gained their independence after ten years of struggle. In 1938, the República de El Salvador was formed.

When Bitter Grieving Explodes in Savage Violence

In 1980, a brutal bloodbath of a civil war erupted in the tiny, densely populated Republic of El Salvador, sandwiched in between Hondurus and Guatemala. One hundred thousand lost their lives in the blood baths before a truce was called.

The twelve year civil war was triggered when Major Roberto D’Aubuisson, head of the Junta’s military intelligence, ordered Archbishop Romero’s assassination.

Over fifty thousand angry, grieving country folks attended the funeral of the beloved martyr. The highly charged funeral procession erupted when a bomb exploded, followed by a fierce firefight between anti-government demonstrators and military forces in San Salvador’s Plaza of the Cathedral. Forty were killed, many of them crushed against a security fence as they fled the mayhem.

Four U.S. nuns working in El Salvador, accused of treason against the government because of alleged leftist leanings, were savagely raped and murdered the same year by government supported thugs.

The Carter Administration, torn between supporting a savage military regime that snuffed out its opponents and the fear of the spread of Communism, suspended military aid to the junta government.

Five separate leftist guerilla groups united, forming the Marxist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The insurgents, convinced that they had popular support, with ill placed confidence expecting a mass insurrection, launched an offensive against the government on January 10, 1981, just before President Reagan took office.

Although the armed forces trounced the poorly armed and trained rebels, the FMLN’s offensive in 1981, which resulted in limited victories, alarmed the Carter administration.

National Interest Prevailed

The fear of the fall of the Central American countries to Communism overcame the revulsion with the way the military government in El Salvador tried to suppress popular opposition. Within a week’s time, the U.S. resumed aid to the military junta to the tune of $10 million.

In spite of its defeat, the FMLN received international recognition and retained military strongholds in Chalatenango and other departments, where its forces settled in for the long-drawn-out civil war. Before the end of the year, France and Mexico recognized the front as a political player.

The staunch anti-Communism Reagan administration issued a special report, “Communist Interference in El Salvador” its first few weeks in office. The statement warned that the Soviet Union and Cuba were supporting and equipping the FMLN in El Salvador, just as they had the Sandanistas in neighboring Nicaragua.

Central America had become another violent Cold War proxy battleground.

The Military Group Goes To War

“El Salvador had a small armed force of approximately 10,000 military personnel and seven thousand paramilitary police in 1980 when the war began. The army, the largest part of the armed forces, had approximately nine thousand soldiers organized into four small infantry brigades, an artillery battalion,and a light armor battalion. The level of training was low…there was no training or preparation for fighting a counterinsurgency campaign. In short, it was an army that was not prepared for war,” Airpower Journal summed up the shape of the rag tag El Salvadoran army in 1980.

By 1984, the El Salvadoran armed forces numbered 42,000, thanks to the United States. Five U.S. Air Force officers were part of the 55 MILGROUP of advisers, along with several helicopter maintenance instructors. El Salvadoran troops were trained in the United States and at the Inter-American Air Force Academy (IAAFA) at Albrook Field in Panama.

As the U.S. Drags its Feet, SOF Jumps In

That’s where SOF’s RKB, who mainly understood the word ‘participatory’ in participatory journalism comes in.

“The measly group of 55 U.S. military trainers in El Salvador can do nothing but bitch among themselves and get on with the task despite the frustrations of having their hands tied by political consideration. Making waves might swamp the leaky boat in which the soldiers float through their assignment in Central America,” the straight shooting Harry, not fond of political correctness, told SOF readers during the thick of the chaos in El Salvador.

SOF put a core group of operators on the ground throughout the entire war. Among them were demolition expert, John Donavan, weapons expert Peter Kokalis, Col Alex McCall, medic Tom Reisenger, and Harry on the ground in El Salvador in 1984.

The U.S. had jumped in because of the so called “dominoes effect.” Nicaragua had fallen to the leftist Sandanista who in turn supported the FMLN in El Salvador. The fear was that El Salvador would go next, and Mexico was in a mess of a shape and could easily fall. Then, of course, the Soviet Union would be in our back door.

SOF’s involvement exposed scandals that did not make the history books such as the El Salvadoran Air Force’s plan to bomb Managua.

A Soldier of Fortune’s Impact on Central America

“I recruited Harry at an SOF convention in Las Vegas in 1984 to go to El Salvador to advise the Salvadoran military,” RKB recalled.

“I said yes without a hesitation,” Harry remembered the meeting that launched his involvement with SOF’s wild adventure.

In June 1984, Harry joined an SOF team that trained the Airborne Battalion—spear headed by its Deep Reconnaissance Platoon headquartered at Ilopango Air Force Base a few miles outside San Salvador.

The Airborne Battalion had the right stuff, as it had just fought off a major insurgent attack on the hydroelectric dam at Cerron Grande, which provided over half of the country’s electricity.

The first tour lasted two weeks and the second one a few months.

“I returned to Ilopango during November and December as an SOF-sponsored trainer. The battalion commander was glad to see me return and we quickly agreed on a curriculum concentrating on the Deep Reconnaissance Platoon, given my Marine Corps Force Recon combat background,” Harry said.

“After he got back the second time, I called Harry,” RKB said.

“You want to go back? How long can you stay?” he barked in his gruff manner.

“‘How much?’ Harry asked, as subtly.

“‘$1000 a month’,” RKB roared back.”

“Hell, it didn’t take much to live in El Salvador and I decided to give it a try. I had been all over the world, in Viet Nam, in India and other parts of Asia, in Europe, and it was time to try something new,” he recalled.

El Salvador was in a shambles. The military desperately needed help.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers