by Carole Engel Avriett

Excerpted from Midnight in Ironbottom Sound, by Carole Engel Avriett.

Editor’s note: Early on September 5, 1942, the US Navy’s USS Gregory was sunk by Japanese fire near Guadalcanal. One sailor, Mess Attendant 2nd Class Charles Jackson French swam for hours through shark-infested waters while towing a life raft with 15 men aboard. Here is his story.

French had lost track of time. He simply had no idea how long he had been in the dark, hellish waters. Every now and then, he would see what he thought was another raft or lone swimmer in the distance, but from his limited vantage point down in the water, it was impossible to make out who or what it was with any certainty.

As the hours dragged by, the sharks seemed to disappear.

“Maybe they just gave up looking for a meal around here,” he thought. He guessed they had been drifting at least a couple of hours. His hands felt like wrinkled sponges, his legs were as heavy as logs. Every now and then, he would rest alongside the raft by looping one arm through its side ropes. And always he would ask Bob Adrian if he was still headed in the right direction: away from shore but not headed toward the vast expanse of the South Pacific at the southernmost end of the channel. “I’m going to tow this ol’ crate in—just keep telling me if I’m goin’ the right way,” French continued to say.

It was during the early morning hours that French began to wonder just how much longer he could last. He had never experienced such debilitating exhaustion. He alternated swimming and pulling with floating during the darkest part of the night—just before dawn.

Neither French nor Adrian had any idea what to expect once daylight arrived. To make matters worse, French thought he felt something once more around his feet—he couldn’t be sure, however. “Might just be my imagination playing tricks,” he thought. He labored to come alongside the raft and hang on for a few minutes to catch his breath.

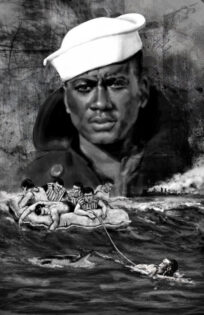

Illustration, author’s collection

As he withdrew his arm and began swimming again, one of the men who had been passed out in the bottom of the raft for most of the night raised himself up. He was disoriented at first and looking around, he spotted Adrian.

“Where the hell are we?” he muttered.

“We’re trying to stay clear of the beach,” replied Adrian.

There was just a sliver of daylight now—enough for the sailor to see more than a few inches beyond his nose. He spotted someone in the water, swimming and pulling the raft.

“Who the hell’s that?” asked the shipmate.

Adrian turned fully toward the wounded sailor and immediately recognized him. He was one of the southern boys from Alabama.

“That’s French, you know, one of the steward’s mates. He’s been pulling us through the water all night, through the sharks and everything—keepin’ us away from those Japs onshore. I’ve been using Orion to help give him directions.”

As the sun broke above the horizon, French no longer required Adrian’s guidance. The lieutenant slumped over in the raft and closed his eyes.

Suddenly, planes were heard overhead; the sound immediately generated anxiety among those in the raft who were cognizant. When they came into view, the desperate men realized they were friendly. Soon landing crafts appeared to pull the survivors in various places in the channel to safety.

The rescue was depicted in True Comics. Courtesy of Swimming World Magazine

Adrian describes their rescue from hell’s waters in his memoirs:

“Early the next morning, several of the Marines’ planes from Henderson Field took off and one spotted us in the water and radioed in our position. Soon thereafter, an LCP (Landing Craft Personnel) came out and picked us up. A later count figured that there were about thirty survivors from the ships in this area. I was one of two that survived the Japs’ direct hit on the port side of our bridge (USS Gregory) where there were about twelve shipmates stationed that night: the Captain, Asst. Gunnery Officer, lookouts, signalmen, and phone talker—all killed by the direct hit on the bridge area.

“When we got ashore, the Marines put approximately twenty of us in foxholes well behind their line of engagement with the Japs. A Navy Hospital Corps (the Marines always retain several well-trained hospital corpsmen assigned to each Company) looked after our wounded. They bandaged up my knee and looked in my right eye and found out it was filled with embedded shrapnel particles or paint fragments (from the bridge bulkhead I was facing while on the phone to the engine room, when we took the hit on the bridge). He was not qualified to try to get them out and simply put a bandage over the eye.

“We soon found out the Marines were having a desperate struggle to keep Henderson Field in our possession and were taking heavy casualties.”

When French, still with the raft’s rope tied around his waist, looked ahead at the shore, he saw several Raiders waiting for them to land. Several began to wade out into the water to assist him and the others. One Raider helped drag him through the shallow waters while others helped unload debilitated survivors. Some had to be carried on makeshift stretchers, but all were alive—and grateful for what French had done.

Once French reached the sand, however, he collapsed. The sailor from Alabama, who had argued many times with the mess attendant about his ability to swim, came up behind him. Though wounded himself, the doubter from Alabama quickly reached down to help him up.

“Man, you did a helluva job last night,” he said to French, who was so tired he could barely respond. The two helped each other move farther away from the deadly waters and into shade.

The 1st Marine Raiders, along with other Marines, assisted the men from the Gregory in crossing the short distance back into the treeline. Eager to help their Gregory friends, they administered as much first aid as they could, provided water, and gave away their rations.

When the surviving sailors related all that had happened, in particular what the enemy had done—deliberately attempting to kill the wounded men in the water with machine guns—the Raiders were left in a cold rage. Many cursed vehemently and vowed retribution.

It soon became evident that most of the sailors suffered some degree of shock. Medics began arriving in the camp to help stabilize the more seriously wounded and try to get them back to the aid stations at Henderson Field.

The USS Gregory (US Navy photo)

As things were beginning to settle down a bit, several military police showed up to check out security and determine if there were any pressing needs. When they spotted French, they ordered him to come with them so they could transport him to the “colored” camp some distance away.

“Hey you, come with us!” one of the MPs shouted to French, who could barely stand. French was trying to hobble over to their jeep when one of the Raiders looked up and saw what was about to transpire.

“Wait a minute—what do you think you’re doing?” the Raider said to the MP. Their racket had caught the attention of several other 1st Marine Raiders as well as the wounded Gregory sailors.

The MP, who now gripped French by the arm and was guiding him to the jeep, kept going. “He’s not supposed to be here—he’s supposed to be in the colored camp,” the guard replied curtly.

By this time the Gregory sailor from Alabama had also heard the commotion and stepped into the scene. “No, no,” he said, shaking his head vigorously, “this man ain’t going nowhere—he’s one of us—he’s staying here!” Almost at once, those sailors from the Gregory who had been pulled throughout the night and could manage to walk, came over and joined the heated discussion. Others who could barely move, nevertheless, added raucous vocal support for their shipmate. Many Raiders were already standing, braced. French, who could barely hold his shoulders up from fatigue, just slumped in the middle—the MPs on one side and the sailors from the Gregory alongside the Raiders—on the other.

The military policemen looked at each other. They could easily identify a lost cause. “As you wish. Let’s go—no use wasting our time here,” they said, and climbing back into their jeep they sped off down the beach.

An excerpt from Carole Engel Avriett’s Midnight in Ironbottom Sound: The Harrowing WWII Story of Heroism in the Shark-Infested Waters of Guadalcanal

Editor’s note: In 2024, Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro announced that the future Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer DDG-142 will be named USS Charles J. French.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers