60 Army Special Operators awards upgraded for Operation Gothic Serpent

FORT BRAGG, N. C. – The U.S. Army approved the upgrade of 60 Army special operators’ awards for their heroic actions during Operation Gothic Serpent—more commonly known as the Battle of Mogadishu or “Black Hawk Down.” Fifty-eight awards were upgraded to Silver Stars and two were upgraded to Distinguished Flying Crosses.

The upgrades are a result of the October 2020 directive from former Secretary of the Army, Ryan McCarthy, who directed the Senior Army Decorations Board to re-evaluate previously approved awards for valor.

The Silver Star Medal is the third-highest military combat award and is awarded in recognition of a valorous act performed during combat operations while under fire from enemy forces.

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded in recognition of heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight.

The upgraded awards will be presented later this year in separate commemoration ceremonies hosted by the units in which the Soldier served at the time of the mission.

Operation Gothic Serpent, led by U. S. Special Operations Forces during the Somali Civil War, took place in Mogadishu, Somalia, from August to October 1993. On the afternoon of Oct. 3, armed militants shot down two MH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, after which U.S. ground forces converged on the two downed aircraft to recover the personnel. The ensuing intense firefight resulted in the loss of 18 American Soldiers and remains an especially significant point in the history of the U.S. Army and U.S. Army Special Operations Command specifically.

2021 marks the 28th anniversary of Operation Gothic Serpent.

5 May 1993 was the bloodiest day in Somalia since the mission began the previous year as a humanitarian mission. One debacle after the other followed, leading up to the famed Blackhawk Down that was launched in 3-4 October 1993. –

By May of 1993, the UN had taken over the mission. Militiamen loyal to Mohamed Farrah Aidid had killed 24 Pakistani soldiers in the escalating battle.

5 May, 2 US soldiers (trucker and engineer) were wounded in the bloodiest day in 3 months during running battles across Mogadishu. An 85 man company from 1/22 Infantry, 10th Mountain Division, had been deployed to repel further attacks.

A month later, 5 June, Admiral Howe, Commander of the mission ordered U.S. Special Operations forces to arrest Aideed. General Montgomery, torn between the Clinton Administration decision to reduce U.S. forces, and needing more equipment made a request for additional equipment and armor for the Forces, which was denied.

In July, Howe offered a $25K reward for the capture of Aideed.

As the chase to capture Aided dragged on, Clinton ordered more forces to Somalia to back up the the Ranger Task Force. The dual command, from Washington and the U.N. was characterized by abrupt shifts and lack of clarity. Ultimately, U.S. officers and officials concluded that the UN had overstepped its bounds in undertaking a Peacemaking and Nation building mission.

The wrangling and tangling in the Senate continued through the summer and leading to the fateful two days when the Rangers raided 3-4 October.

Glenn S. Robertson reports on the Mogadishu Mile and the Blackhawk Down disaster:

Beginning at 5:42 a.m., October 4, 1993, U.S. Army Rangers, and soldiers of Delta Force and the 10th Mountain Division began retreating from Blackhawk helicopter crash sites after the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia.

Nineteen Americans died and 73 more were injured in the battle, but those who survived the initial firefights were not out of harm’s way. They had another hurdle – exfiltration to a rally point held by the 10th Mountain Division and an awaiting convoy.

A convoy of UN troops driving more than 100 vehicles entered the city to extract the survivors; however, a group of Rangers and Delta operators, along with soldiers from the 10th Mountain would have to join the convoy on foot after the wounded had been loaded onto the vehicles.

Thus began the Mogadishu Mile, where the convoy and troops on foot conducted a tactical retreat from the crash site to a location on National Street where more vehicles awaited to take them to secure locations all while under attack from small arms and rocket propelled grenade fire.

October 3, 1993

3:42 p.m. : Assault teams strike the Olympic Hotel target site in an attempt to capture two lieutenants of Mohamed Farrah Aidid, the leader of a combatant force in opposition to UN peacekeeping efforts. Four Delta assault “chalks” drop from helicopters and move to the four corners of the hotel.

PFC Todd Blackburn falls while fast roping from Super 67 in the first moments of the operation, suffering multiple injuries. He is evacuated by a ground support convoy, and Sergeant Dominick Pilla, a Ranger assigned to the convoy, is killed while taking Blackburn back to safety.

“We’re doing this as a memorial to those 18 Rangers and Delta Force operators who died,” said Senior Master Sgt. Bartsch, who organized the event. “However, we’re also here to honor the sacrifice and heroism of all of those present, including three Airmen.”

4:20 p.m. : Blackhawk Super 61 is shot down by an RPG. Both pilots are killed in the crash and their crew chiefs wounded. Delta Staff Sgt. Daniel Busch and Sgt. Jim Smith survive the crash and begin defending the site. Busch later dies of his injuries, having been shot four times while defending the crash site.

Eleven Airmen, mostly from the 90th Communications Squadron, donned rucksacks and marched 2.8 miles around the parade field to match the distance from the site of the downed helicopter to the site called the Pakistani Stadium, a secure UN facility set up with medical support for the special operators.

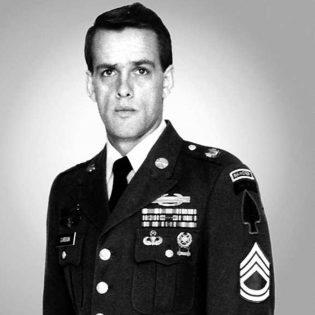

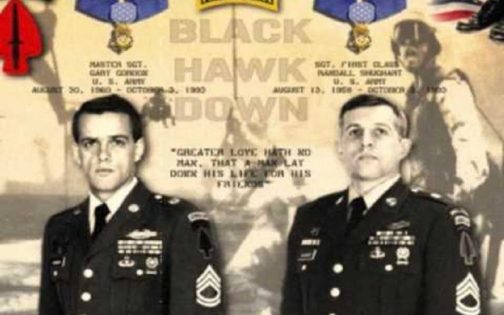

4:40 p.m. : Super 64 is downed by an RPG. Sergeant First Class Randy Shughart and Master Sgt. Gary Gordon, who had been providing cover fire from the air, request to be inserted into the crash site. After several denials of their request, they are allowed to drop into the site to protect the crew of 64.

Many of those Airmen participating were not even alive during the events of the Battle of Mogadishu, but that fact was no deterrent to them paying their respects through the event, even if they had never done anything like it before.

5:40 p.m. : Shughart and Gordon run out of ammunition and are overrun by Somali combatants. They and the pilots and crew of 64 are killed, except for pilot Chief Warrant Officer Mike Durant, who is savagely beaten and then taken prisoner. He will be released after 11 days in captivity.

“I came out because the squadron was doing it and I’d never done a memorial ruck before,” said 2nd Lieutenant Adam Nelson. “It was a new experience and I wasn’t really sure what to expect.”

5:45 p.m. : Ninety-nine men remain trapped and surrounded in the city around Super 61. They fight off wave after wave of hostile Somali fighters.

Though for some it was a desire to increase camaraderie by participating in an event with their unit, some saw it as an appropriate capstone to their own career through honoring those who came before.

9:00 p.m. : Joint Task Force Command organizes “The Rescue Convoy,” composed of 10th Mountain Troops, the remainder of Task Force Ranger, Pakistani tanks and Malaysian armored vehicles. They move out in less than thirty minutes but are stopped by a large explosion close to the crash site. They reach the trapped soldiers just before 2 a.m.

Twenty-seven years have passed since the battle and the extraction, but Airmen of the 90th Missile Wing held a Mogadishu Mile ruck march Oct. 9, 2020 at the parade field on F. E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyo., to honor the sacrifice and bravery of those who fought and died that day.

“I participated as a way to remember the sacrifices and the lives of those who came before me, and this was a perfect way to end my active duty career with a humbling event where everyone there took time to remember and reflect on the battle and give some of us newer Airmen a way to learn our history and give back in a sense,” said Staff Sgt. Anthony Stancil. “Although it was before my time, it was a significant event that embodied warrior ethos, courage, and heroism.”

October 4, 1993

5:30 a.m. : Elements of the Rangers and Delta Force soldiers begin the “Mogadishu Mile,” exfiltrating to a rendezvous point just over a mile away on National Street, all while taking withering small arms fire and RPG attacks.

To kick off the march, Bartsch quoted Tech Sgt. Tim Wilkinson, a pararescueman who earned an Air Force Cross for his heroism during the battle from a statement he gave upon receiving the medal.

6:30 a.m. : The force returns to the stadium. Of the 99 Americans on the ground, 18 Americans will be confirmed dead and 73 injured.

“Today you have honored us and we are humbly grateful – humbly grateful because although we are privileged to enjoy the honors you have bestowed upon us, one must be humbled by the sacrifices of our comrades who are no longer with us – our fallen teammates who have given the fullest measure,” said Wilkinson. “There is no greater love than for one man to give his life for another, and we would ask that as you have honored us today that you remember our fallen teammates and when you remember these events of Oct. 3 and 4, you remember them, their families and their loved ones.”

By Glenn S. Robertson,

Editor’s Note: Wilkinson, along with pararescueman Master Sgt. Scott Fales and combat controller Tech Sgt. Jeffrey Bray, were among those 99 men fighting for their lives and the lives of their comrades through the streets of Mogadishu in 1993. Fales and Bray earned Silver Stars for their valor in the face of unyielding attack. During the fight, Bray innovated tactics on the spot that would become instrumental in urban combat in the post-9/11 combat area. Bray passed away in 2017. An article about their experience can be found here.

Battle of Mogadishu hero passes, leaves behind legacy

By Senior Airman Ryan Conro

A former special tactics combat controller responsible for saving dozens of lives at the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia in 1993, was laid to rest recently, leaving behind a far-reaching legacy of valor, professionalism and combat success.

Nearly 100 friends, family and teammates gathered to honor retired Tech. Sgt. Jeffrey Bray, a Silver Star recipient, at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, Dec. 30, who passed away Oct. 24 at 49 years old.

“It is always tough to lose a national treasure like Jeff,” said Col. Michael Martin, the 24th Special Operations Wing commander. “He meant so much to so many; it was incredibly moving to lay him to rest surrounded by his family and teammates.”

Bray’s contributions to the Air Force, and to special operations, was nested in an experience that would define how special tactics operated in urban warfare. On Oct. 3, 1993, Bray was attached to a joint service team responding to the crash of a U.S. Army MH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, which was shot down in Mogadishu.

Under fire, trapped and surrounded inside a building in the city, Bray coordinated helicopter gunship fire on targets all around his position throughout the night. Without previous experience in this environment, he developed tactics and techniques on the spot that allowed him to mark friendly forces’ locations so that helicopter gunships could destroy close enemy concentrations.

Bray wasn’t the only Airman there; the joint search and rescue team also included pararescuemen Master Sgt. Scott Fales and Tech. Sgt. Tim Wilkinson, who earned a Silver Star and Air Force Cross respectively, for their actions during the mission. Wilkinson and Fales –part of the 15-person joint team—were responding to the downed helicopter, while Bray and the U.S. Army special operations team were to capture Mohammed Farah Aideed’s top lieutenants. When the mission deviated due to overwhelming forces, it became a matter of survival. Wilkinson and Fales worked on the wounded as Bray coordinated airstrikes and strafing runs to keep the enemy at bay.

“I think the dynamics of that particular incident provided us a good bit of perspective to reevaluate the way we do business from a personnel recovery and air-to-ground coordination standpoint,” Wilkinson said. “At the time, there wasn’t a lot of urban warfare and it gave us a really good look at how we conduct operations in an urban environment.”

A 1994 Airman magazine interview revealed a clearer understanding of the tactics Bray innovatively developed to ensure friendly fire was avoided and protect his teammates. Bray would send runners out to mark locations with infrared strobe lights that only orbiting U.S. aircraft could see. The runners found targets and relayed the information to Bray; he would plot each location and call in the fire. He then plotted the locations out beyond the targets and corrected the airstrike fire by walking it in to enemy positions. At times, he coordinated fire on enemy locations only 15 meters away.

His expertise in controlling air-to-ground fire prevented friendly fire casualties and were integral to the survival of the Army special operations team, according to the citation.

“Jeff was innovative, able to think on his feet, very calm and collected,” said Wilkinson of Bray in Mogadishu. “He did an outstanding job. I think I speak for the entire community when I say Jeff was a consummate teammate, professional and friend, and he will be sorely missed.”

However, to many, Bray’s legacy is beyond his Silver Star; according to his teammates, he was one of the few special tactics Airmen who had directed airpower during intense urban warfare—a precursor to what many would experience in Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom.

This experience in urban warfare translated into a level of training unlike most could provide. Bray was later a training and cadre member for his special tactics unit. Here, his vigor and experience on the battlefield translated to a dynamic change in the way his team conducted urban warfare preparation, according to one of Bray’s former students.

“In Mogadishu, Jeff saved dozen of lives: men who were able to come home and either return to their families or someday start a family of their own,” said retired Col. Kurt Buller, a former special tactics officer. “As an instructor, he was exceedingly demanding of our technical skills … his training kept us alive in combat, I’m sure of it.

“The majority of the guys Jeff taught went on to fight post 9/11 and were tested the way Jeff was tested,” Buller continued. “Besides being a great person and a great operator — his legacy was the training he provided to the scores of guys at the squadron, who would ultimately go on to be successful in combat as well.”

While Bray’s legacy and name have been solidified in history, he leaves behind a family, a wife and teammates who served alongside side him throughout his career.

“Jeff transformed special tactics generationally, and we will never forget his actions,” Martin said. “The special tactics community will always maintain overwatch of his wife, Sherry, and his family.”

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers