Former Staff Sgt. Ronald Shurer II, the hero of Shok Valley, MOH recipient has lost his long battle with lung cancer. R. I.P Sir. With all the battles Shurer has gone through, he faced one more in recent years. March 2017, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which had spread throughout his body.

His story:

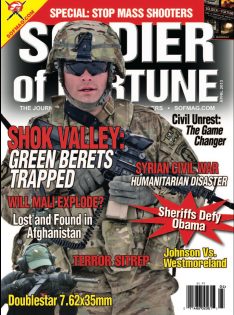

This is the team’s medal’ says Shok Valley Medal of Honor recipient

SOF April 2013

By Devon L. Suits Army.mil

BURKE, Va. — As Soldiers progress through their career, they often obtain certain momentos that commemorate their time spent in uniform. Having spent six and a half years in the Army, former Staff Sgt. Ronald Shurer II has many keepsakes.

The former Special Forces medic proudly displays his Green Beret next to a folded American flag and a vinyl record by singer/songwriter Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler. The Shurer family’s quaint Virginia home is filled with reminders of Ron’s time with 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne), his two deployments to Afghanistan, and his career with the U.S. Secret Service.

However, some keepsakes — some memories — are best kept closed. The cases holding Shurer’s Silver Star and Purple Heart remain shut as they rest close to his Green Beret. He received those medals for his actions on April 6, 2008.

Shurer chooses to conceal his Desert Camouflage Uniform, which he wore during an operation in Afghanistan’s Shok Valley.

The blood that once drenched his uniform has been thoroughly washed away. The only visible detail from the hellacious battle is a small bullet-sized tear on the uniform’s left sleeve. Nevertheless, the memories surrounding the day Shurer almost died still remain.

President Donald Trump will present Shurer with the Medal of Honor on Oct. 1 at the White House for his heroic actions on that fateful day in 2008, when he saved four critically wounded Special Forces teammates and 10 Afghan commandos.

“I’m not a hero,” Shurer said humbly. “I just happened to be the medic there that day. The guys trusted me to help them, and I was going to do everything I could not to let them down.”

APRIL 6, 2008

It was an early morning departure for the 15 Special Forces Soldiers on April 6, 2008. Boarding a number of Chinooks near Jalalabad, Afghanistan, approximately 100 Afghan commandos joined the Special Forces team in preparation for their upcoming mission.

The joint team had recently received information that a high-value target was operating out of an isolated village in the Shok Valley.

“We don’t go out on a mission where we don’t expect to meet some resistance, but this was unlike anything we’d ever faced before,” Shurer said.

On a map, Shok Valley resembles a lowercase “y” with the enemy’s fortification sitting at the heart of the minuscule character, Shurer said. The enemy encampment — a village recessed on the summit of a mountain — contained a series of stacked buildings and provided a semi-clear view of the valley below.

The joint attacking force was relying on the element of surprise as they infilled just south of their objective. As the team’s only medic, Shurer was in one of the last heavy-lift helicopters to arrive on the scene.

“I distinctly remember it was taking for what felt like forever for everybody to get off,” Shurer said. “As I made it toward the back of the Chinook, that’s when I realized that they were having to hover about 10 or 15 feet off the ground. Just like everybody before me, I carefully tried to slide off the back, so I didn’t break my leg getting off the helicopter.”

“Once I hit the ground, I remembered being surrounded by mountains,” Shurer said. “After the Chinooks left, it was just kind of cold and quiet.”

From there, the combined attacking force broke into smaller teams and began the treacherous hike through the river. As a member of the trail element, Shurer and the rest of his team approached the base of the hill while the lead element started their climb, he said.

Parts of the mountain were steep, and it felt like the team was trying to scale a straight wall, he added.

“I’m not quite sure how long it was, but a few minutes after we started to move up the mountain, we saw a couple people running around on top of the hill,” Shurer said. “Just like any of the valleys — when you fly through, they will know you’re coming.

“They had a plan for this day, and they began executing their plan as we got into position.”

Moments later, “it felt like everything exploded around us,” Shurer recalled.

An onslaught of rocket-propelled grenades and small arms and sniper fire rained down from the enemy’s location, forcing the elements to secure cover. Instantaneously, helicopter and fixed-wing close air support started a series of attack runs and air strikes on the enemy.

“That’s when I first heard the calls for help,” Shurer said.

FINDING HIS PATH

Born in Fairbanks, Alaska, Shurer spent most of his youth moving around the U.S., until his family settled in the state of Washington.

“[The] military was always part of my family’s history. My grandfather served during World War II. My father did 20 years in the U.S. Air Force. And my mom did time in the Air Force. It was always just something that my family did.”

While growing up, Shurer never felt any pressure to join the military. Everything changed after Sept. 11, 2001.

“I enlisted in the fall of 2002. I was in graduate school at the time getting a degree in economics,” Shurer explained. “After 9/11, just seeing the stories coming back from overseas, it felt like the right thing to do. So, I left halfway through the program and enlisted in the Army.”

Selected to be a medic, Shurer completed his Advanced Individual Training in San Antonio, Texas. From there, he went to Airborne school and eventually made his way to the 261st Area Support Medical Battalion at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

“It was a good unit, but I made a choice to put in a Special Forces packet,” Shurer said. “In January of 2004, I went through the Special Forces selection process and was selected. I started the actual qualification course in June of 2004.

“The only thing that makes Special Forces different is just doing the basics (correctly) while under stress. We drilled those basics over and over again until it became second nature,” he added.

Around the same time, Shurer met Miranda Lantzwere online, and their conversations developed into a budding romance.

“While he was in the Q course to become Special Forces, I was at James Madison University, in graduate school for counseling psychology,” Miranda said. “We lived five hours away from each other, and we talked for a few weeks before he offered to drive to meet me.

“I just thought he was really sweet, funny, and witty,” she added. “He was doing this job where he was going to be one of the toughest Soldiers for our country, and yet Ron would say cute things (like) ‘when he eats a bag of gummy bears, he saves one to help repopulate the species.'”

To this day, Shurer and his now-wife Miranda still possess a small keepsake from their first encounter. On one of their living room shelves, a framed movie ticket stub shines like a beacon among an assortment of family momentos and photos.

“I always knew, as a medic, how invested he was and how much it meant to him,” Miranda added. “We would spend weekends together, and we would spend time going over flashcards to study for the course.

“To Ron, it wasn’t just about passing the course. It was about needing to know the information because it was going to matter one day,” she said. “Thankfully, when the time came, Ron had those skills, and he was able to utilize them.”

Shurer graduated his Q course in May of 2006, and the couple became engaged soon after. A few weeks later, he reported to the 3rd Special Forces Group, which was preparing for an upcoming deployment to Afghanistan.

Shurer and Miranda moved up their wedding date and married. Through time, their family grew to include two boys.

“My wife is an amazing woman,” Shurer said. “She has put up with a lot.”

THEY CALLED FOR ‘RON’

As all hell broke loose in Shok Valley, the calls for help came in. Shurer’s training instantly kicked in as he tended to an Afghan commando who had sustained a gunshot wound to the groin. Fortunately, his injury was not severe.

“Just as I was finishing up with him, that’s when the calls for ‘Ron’ started to come down the line. I knew instantly that Ryan was hurt,” Shurer recalled.

Before every mission, former Staff Sgt. Ryan Wallen would grab his commandos, take them to Shurer, and tell them: “If something happens to me, find Ron!”

With no reprieve from the enemy fire, Shurer sprinted to his injured friend. Ryan was lying near the base of the mountain and had sustained a shrapnel injury to his neck from a rocket-propelled grenade. Shurer did what he could to treat Ryan’s injuries.

As he treated his teammate, Shurer’s attention was diverted to the radio chatter from the lead element requesting support. The team was pinned down at a higher elevation along the hillside and had sustained several injuries.

“I didn’t know exactly how many of them were injured at the time, but they were wounded,” Shurer said. “So quickly, I gathered up my stuff, moved through the river, and started moving toward the hill.”

At the same time, a small team of Special Forces Soldiers and Afghan commandos were mobilizing to reach the lead team’s location, he said. Shurer joined them and fought his way across several hundred meters, killing multiple insurgents.

“Once we got up there, I saw three guys down. A couple of Americans looked severely wounded,” he said. “One of the Afghans — our interpreter who went by C.K. — he appeared dead at that time.”

Shielded by a small crest on the hillside, the forward element continued to fight the enemy as Shurer moved in swiftly to start triaging his downed teammates. Bullets ricocheted all around him, kicking dust into his face.

“We tried to be as inconspicuous as possible out there,” he said. “There was just a constant reminder that we were not in a safe position. We needed to try and stabilize everybody as quickly as possible and then get them out of there.”

Shurer first started working on then-Staff Sgt. Dillon Behr, who had sustained an injury to his arm and upper pelvis.

“Dillon was complaining that his leg didn’t feel like it was straight, which made me worried that it hit his pelvis or femur and did a lot of damage,” Shurer explained. “It was a small wound, but knowing how bullets can act sometimes, I didn’t know what was on his other side.”

Shurer carefully maneuvered Behr to discover the location of the exit wound. With a better understanding of his injury, he still needed to find the best way to treat Behr’s wounds. Until he could formulate a plan, Shurer enlisted the help of then-Spc. Michael Carter, the team’s combat cameraman.

“[Carter] kind of became invaluable to me up there. I put a bandage on [Behr] and asked [Carter] to hold pressure while I went to go do some other work,” Shurer said.

The next person Shurer tended to was then-Staff Sgt. Luis Morales, who had received gunshot injuries to his thigh and foot. Fortunately, Luis didn’t have any severe bleeding, but he had sustained severe damage to his leg. To help stabilize him, Shurer bandaged up his injuries and did what he could to prevent shock.

Surrounded by turmoil, Shurer still took a brief, yet apprehensive, moment to check C.K.

“I owed it to him to see if he was alive,” Shurer said, followed by a pause. “Unfortunately, with the injury he received to his head, it was an unsurvivable wound.”

PAYING RESPECT TO A FRIEND — C.K.

In the Special Forces community, interpreters become a vital part to each mission’s success, said Shurer.

“When you’re trying to lead the squad, there are certain universal soldier body languages and hand and arm signals that you can do. However, you still have to rely on that interpreter to convey a deeper meaning,” he said.

At the time Shurer was deployed, Special Forces units typically maintained a seven-month cycle in and out of the area of responsibility. To help preserve the fidelity of the mission, Afghan commandos and interpreters — like C.K. — were always there to provide support, he said.

“His real name was Edris Khan,” Shurer explained. “Our interpreters became part of our team — part of our family. C.K. wanted to become an American, and he wanted to help Americans in the fight.

“Unfortunately, he was killed that day.”

To help pay respects to C.K., Shurer and Miranda decided that Edris would be their second child’s middle name.

“We just wanted to pay respect to him and bring [a piece of him] to America, to help achieve his goal,” Shurer said.

TRIAGE, FIGHT, EVACUATE

“On the hill, we made peace that — today was the day where a lot of us were going to die,” Shurer confessed.

“It definitely felt that I was going to die. I just said a prayer and asked that my wife and son would be okay with what was going happen,” Shurer recalled. “Then I just went back to work to continually re-triage everyone.”

After stabilizing Morales’ leg, Shurer returned to Behr, who was still bleeding out from the hip. With the wound in such an awkward position, Shurer had no choice but to dump powdered hemostatic agent onto Behr’s injury and pack it in with fingers, he said.

Around the same time, then-Staff Sgt. John Walding arrived in the area with several Afghan commandos to support the evacuation of casualties. As Walding tried to move personnel, a sniper connected with a hit to his lower right leg, effectively amputating his limb right below the knee.

“Because I was working on [Behr], I couldn’t get over to him right away. So, I just directed someone to get a tourniquet on [Walding’s] leg to try and get control over his bleeding,” Shurer said. In the interim, he continued to bandage Behr’s wounds and started him on an IV.

Through all the chaos, then-Master Sgt. Scott Ford, the team sergeant, was still leading the fight to help aid in the force’s retreat. As Ford barked out orders to his commando element, a sniper took aim and made contact with Ford’s chest plate, knocking him to the ground.

“I ran out to him,” Shurer said. “He was okay … after having been shot. He immediately got back in the fight.”

Just moments later, another sniper bullet collided with Ford — this time penetrating his left arm and bouncing off Shurer’s helmet.

“It felt like I’d been hit in the head with a baseball bat,” Shurer recalled. “I quickly tried to check myself … but I knew [Ford] needed help. So, I just asked a couple of guys if I was okay, and they said, ‘yes!'”

After Shurer was reassured that he wasn’t injured, he retrieved a tourniquet, hastily applied it to Ford’s arm, then dragged him to cover. However, with all the injuries, Shurer was running out of space to put injured personnel. Fortunately, his team sergeant had enough strength to move down the other side of the hill.

“The entire time there was still danger-close air support,” Shurer said. “As the bombs were hitting on top of the hill, we were catching all the debris that was falling down. Sometimes we would hear a radio call that a strike was going to happen. Sometimes you would just hear that little sound the bomb makes right before it went off.

“I was just trying to cover the guys, because at that point they were definitely very exposed, very vulnerable to, to the environment,” he added. “So I just tried to keep them from getting further injured on top of everything they had already gone through.”

As the fight continued, Shurer did all he could to help treat the growing number of injuries to the team’s Afghan counterparts. In time, then-Sgt. David Sanders and Carter found an alternative route to get casualties out of the area of operations.

According to Shurer, the new route was more treacherous than their initial entry point. Although the path provided the retreating force with more cover, the team had the daunting task of moving casualties down a series of steep pitches.

“I think [Sanders] said something to the effect of: ‘You know, they won’t die to go this way,'” Shurer explained. “So, it was the best call we had. I just started getting everybody ready for the move down the hill.

“We used tubular nylon webbing to kind of wrap it around the guy’s shoulders and lower them down to the next group. We did it as carefully as we could, to not cause further injury. And then, we just kind of repeated that process down the hill.”

Morales was the first to go, followed by Behr. Walding was the last operator to be moved. However, Shurer noticed that his leg injury was still bleeding heavily since the tourniquet had not been administered correctly.

“So, I fixed the tourniquet to stop that bleeding, and packaged him up,” Shurer said. “Then I started working him down the hill. Around that time, that’s when [then- Sgt. Matthew Williams] and [then-Staff Sgt. Seth Howard] had joined us. They started helping to push more guys down the hill that were less severely wounded.”

At the base of the hill, the team set up a casualty collection point. Once Shurer arrived, he bounced from patient to patient, re-checking his work.

“[Behr’s] IV was ripped out and needed to be reset. I re-bandaged everybody and kind of started getting everybody organized while we waited for the evac helicopters to come in.”

One by one, evacuation support made its way into the area, and Shurer ensured a smooth transition for all injured personnel.

“Once everybody was on, I went back and found my commando squad and got back in the fight until it was time to leave. There were a few more casualties that I had to address, but nothing that severe,” he recalled.

The entire operation lasted about six hours. During that time, a bullet grazed Shurer’s arm. However, he cannot recall when or where he received his injury.

“What kept me grounded and focused was the team. Everybody keeps each other honest, keeps each other humble. You can’t pretend when you’re living with people in such close quarters for long periods of time,” he said.

“You see their strengths. You see their weaknesses, you see their good or bad days. And everybody’s just working for that common goal to accomplish the mission and get back home, get back to their families.”

THE HARD CALL HOME

As the wife of a Special Forces Soldier, Miranda remembered having this innate ability to tell when her husband was about to depart on a mission.

“Of course, they couldn’t tell us when they were going out on missions. However, when your husband calls you, you can tell the difference when you just say ‘I love you,’ and when it’s an ‘I LOVE YOU!'”

With an internal clock running in her mind, Miranda typically could gauge when she would hear from Shurer again. That time came — and passed.

Meanwhile, in Afghanistan, the joint team had just been extracted from their violent fight. The severely wounded U.S. and Afghan personnel were evacuated to facilities within the region, Shurer said.

At first, “we ended up landing at some forward operating base. I immediately went over to the aid station, reloaded my bag, and went back to the helicopter and just waited to see what we were going to do next,” he said. The team was ordered to return to base.

Miranda started to worry.

“I was scared enough that I actually got my 3-month-old, [and said] ‘We’re leaving because I didn’t want to sit around the house all day, waiting for a knock on my door,'” she recalled, tearing up.

As she arrived at a store parking lot, Miranda received a call from another Soldier’s wife, who provided information about the operation.

“(She) told me that something had happened. She had a rundown of the men that are injured. Then she was like, ‘I haven’t heard anything about Ron so that probably means he’s fine.’

“In my mind, she wouldn’t have heard anything about him if he didn’t make it because they wouldn’t have released that until they contacted me,” Miranda said.

After Shurer had returned to Jalalabad, he went to check on his injured friends, refit his gear, then made that hard call home.

“Thankfully it was only about a half an hour after that call before Ron was able to call me,” Miranda said. “I had already heard the stuff happened, but hearing that he was okay was definitely amazing.

“One of the first things he said was that everybody did amazing and they all worked together. That’s how everybody on the team was able to make it out that day.”

THE TEAM’S MEDAL

As the calls from high-ranking DOD officials starting flooding in, Shurer never once entertained the notion that his Silver Star was going to be upgraded to the Medal of Honor, he said.

After a series of calls, “I was told to come by the White House,” Shurer said. “They told us they were going to have a meeting with some people … so my wife and I went.”

Shortly after arriving, Shurer’s escorts requested that they talk in another office. However, as a member of the Secret Service’s Counter Assault Team, Shurer was quite familiar with the White House. He immediately knew something was up.

“Instead of taking us to their office, they took us into the Oval Office. President Donald Trump was waiting there, and he informed us my Silver Star had been upgraded,” Shurer shared. “(I was) confused, convinced that it was some mistake or clerical error or something. It just didn’t make sense.”

Miranda was so proud to be part of that momentous occasion.

“It’s the biggest honor a Soldier can ever receive. But at the same time, I knew that the attention was something that was going to be a little difficult for him,” she said.

After meeting the president, the Shurers were happy to share the news with their kids.

“They’re going to remember seeing their dad go through this,” Miranda added. “I think that most boys with great dads think that their dad’s a hero. Now, the whole country is going to think he is a hero. So how cool is that.”

Shurer reached out to his Special Forces teammates to share the good news. He said the team was excited and proud; however, he would prefer to use his recognition to highlight their stories and accomplishment, not his.

“This award is not mine,” he expressed. “This award wouldn’t exist without the team. If they weren’t doing their job, I wouldn’t have been able to do my job.

“Growing up, the Medal of Honor was just so much bigger than life. To even consider that my name would be put in with a group — it just doesn’t make sense to me,” Shurer said. “There are so many amazing stories out there, from guys doing amazing things. I just took care of my guys, got as many of them home as I could.

“I just hope that I can give the Medal of Honor the credit it deserves,” he continued. “Not on myself, but on the guys who are still out there doing the mission right now. All the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines that are out there missing birthdays, missing important moments at home — because they know how important their mission is.”

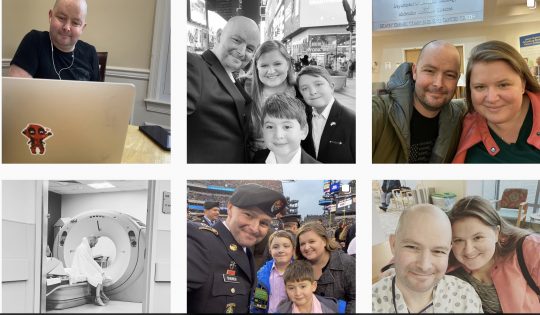

STAYING STRONG

With all the battles Shurer has gone through, the fight is far from over. In March 2017, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which had spread throughout his body.

“We just kind of looked at it as the next challenge,” he said. “We found a great group of doctors and nurses up at Johns Hopkins that we can work with. We have just been following their plan as best we can and trying to enjoy the time with the kids, family, and friends.”

Since being diagnosed, Shurer has been taking medication to help keep the cancer at bay.

One day, he will pass on his keepsakes to his family — which will now include the Medal of Honor. But until that time comes, he continues to fight, relying on the traits and skills he gained through his time in the Special Forces and the Secret Service.

“In the Army, the team depended on me. In life, the family depends on me. My young kids are depending on their dad,” Shurer said. “I can’t quite do as much as I used to, but I’m still going to get out to their sporting events. I’m still going to try and wrestle with them as much as I can.

“I am still going to try and be there.”

Below is the latest in Ronald Shurer II horrific battle with cancer.

Very upset to write this…. been unconscious for a week. They are going to try and take it out in a couple hours, they can’t tell me if it will work. #shurerstrong #specialforces #sfsg #usss #ussscat .

— Ronald J Shurer II (@ron_396) May 13, 2020

.

.

.

.

All… https://t.co/TdY8ejdNmh

Brain radiation today! It’s been a hard end of the year, but we’ve been working almost daily with my docs throughout the holidays to figure out our best path forward. We are closing in on a trial that holds promise,… https://t.co/BEc9UjyWhX

— Ronald J Shurer II (@ron_396) January 6, 2020

Fifteen months after he stood at the White House to receive the nation’s highest combat honor, he’s squaring off in an all-consuming battle against life-threatening lung cancer that his doctors rate at stage 4, meaning it has metastasized or spread to other organs.

“It’s everywhere,” Shurer, 41, said in a lengthy Jan. 22 interview at the coffee shop, military.com reported in a got wrenching interview

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers