by Susan Katz Keating

The Soviets called it Chernaya Gora: Black Mountain. That is where a unit of elite Spetsnaz forces met their deaths in Afghanistan, atop a remote observation post overlooking Kunar. I learned about the treacherous place in 2015, while researching an article for the Army National Guard.

The Guard’s GX Magazine had asked me to write about a soldier who’d been deployed many times, and had garnered a high number of medals. I asked my subject, then-Sergeant First Class John Melson, to connect me with men he served with on deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. I randomly called a name on the list, a decorated soldier I’ll call Gaius, because he reminds me of an ancient warrior.

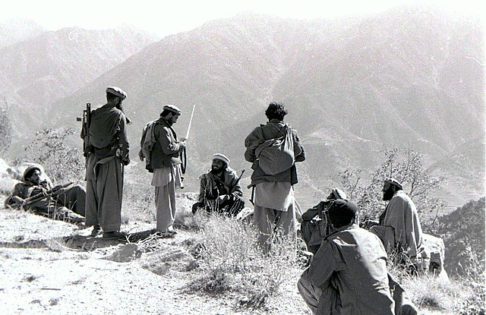

Gaius told me that in 2011 he’d served alongside Melson’s platoon in Kunar Province, the dangerous northeastern section of Afghanistan, that sits on the border with Pakistan. Gaius and the platoon were assigned to Provincial Reconstruction Team Kunar, on Forward Operating Base Wright. Gaius said he was present on FOB Wright when members of this platoon, who called themselves the Mad Dogs, engaged in a brutal firefight against the Taliban. The fight took place atop an old Soviet overlook now known as Outpost Nevada. The Americans were surrounded there under heavy fire without backup. That fight – the Battle of OP Nevada – raged for more than 18 hours.

“Those men were pure warriors,” Gaius told me.

A Story of Battle

For decades, I have written about warfare. I’ve delved into conflicts including the Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Iraq, and Afghanistan. I’ve been on the ground amid urban fighting in Northern Ireland, and in tight situations in the Balkans and among Chechens in Boston. Against that framework, the 18-hour firefight caught my attention.

I asked Gaius to elaborate. While he recounted the battle, I took six pages of notes. Finally, as I turned to the seventh page, I set down my pen and simply listened.

I was captivated; not only by the tale Gaius told, but also by his tone and his insights. This warfighter had a catch to his voice. He kept stopping to compose himself. He clearly was moved by what the soldiers endured, and by how they conducted themselves.

The battle took place while the Americans found themselves on “Desperate Ground,” a phrase coined by the ancient Chinese tactician Sun Tzu, who applied the term to situations where soldiers have no option but to fight without delay. It is a fight to the death.

Eventually I would learn that the battle of OP Nevada played out on multiple fronts and in multiple forms that went beyond a single firefight.

The story involved a disparate group of soldiers. Some were seasoned combat veterans. Others were new to military service. Overall, they included a former nightclub manager, a pizza delivery man, a competitive skateboarder, a used car salesman, a mysterious veteran rumored to have served in the French Foreign Legion, and a passel of self-described “broken toys.” Their platoon sergeant, Melson, was a convicted felon who spent time in prison after being charged with kidnap and assault. The men served in the Army National Guard, whose initials – NG – have sometimes been the butt of jokes that the letters stand for No Good.

As the daughter of a Guardsman who fought in Korea, though, and as the author of numerous articles about the Army National Guard in combat, I knew that the label was misplaced.

The Virginia Guard was part of the first frontal assault on Normandy, storming Omaha Beach. The California Guard – my own father among them – relieved the beleaguered 24th Infantry Division in Korea.

Now, while writing for GX Magazine, I learned about a new group of “NG” warriors: the men from the mountaintop battle. These were soldiers from the Massachusetts National Guard, whose predecessors fought the earliest engagements of the American Revolution, at Lexington and Concord. These latter day fighters were soldiers from Second Company’s “Dog Platoon” of the 1-182 Infantry.

Their legacy in hand, the Mad Dogs in Afghanistan marched in the footpaths of warriors from years gone by: Macedonians under Alexander the Great; Mongols under Genghis Khan; and Soviets directed by Leonid Brezhnev.

Like Alexander before them, the Mad Dogs met a determined enemy in Kunar. Like the shock troops of Spetsnaz, the Mad Dogs endured hell while isolated. Atop the same remote outpost where Spetsnaz fell to their attackers, the Mad Dogs were surrounded and outnumbered. They ran out of food, water, and ammo. And as with Spetsnaz, the Mad Dogs’ ordeal unfolded under the radar and slipped into obscurity, forgotten by all but the participants.

The men weren’t merely forgotten; they also were undocumented.

While researching the battle, I contacted the Army’s 25th Infantry Division, the element in charge of Kunar at the time. The historian there told me the timeframe I asked about had been an extraordinarily busy period for the 25th. The division then had been embroiled in Operation Hammer Down, aimed against Taliban operations in Kunar. Most of the files from then pertained to that action. The historian found no records even referencing the 18-hour firefight on OP Nevada.

The Massachusetts National Guard, for its part, similarly came up empty – and then some. I contacted the Military Division for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to ask for copies of After Action Reports pertaining to OP Nevada. Leonid Kondratiuk, a retired colonel who is Director of Historical Services there, told me After Action Reports did not exist, period.

“The Mass Guard doesn’t write AAR’s,” Kondratiuk said. “No one in the Guard does. They just don’t write them.”

“That’s Not Combat”

Even the former Marine Corps four-star General and later Defense Secretary James Mattis, who oversaw military operations in Afghanistan at the time, drew a blank when I asked him about the event that occurred under his watch.

Mattis hadn’t heard of the Battle of OP Nevada.

Nor did he believe that it took place.

“How many Americans died?” Mattis asked me.

“None,” I said.

“That’s not combat,” Mattis said. “I know combat, and I can tell you, if no Americans died up there, that wasn’t combat.”

Make no mistake, though. When these National Guardsmen found themselves on Desperate Ground, they fought. Isolated from support, abandoned to fate, surrounded by relics of Spetsnaz ghosts and attacked by a relentless enemy, they fought. The extended slugfest was so brutal, so primal, so raw, that the Taliban afterwards refused to re-engage.

As Gaius told me: “What those Americans did up there is pure heroism. They were stunningly courageous. I will never forget them.”

Neither will I.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor-in-chief at Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers