JAN. 17, 2022 | BY KATIE LANGE, DOD NEWS

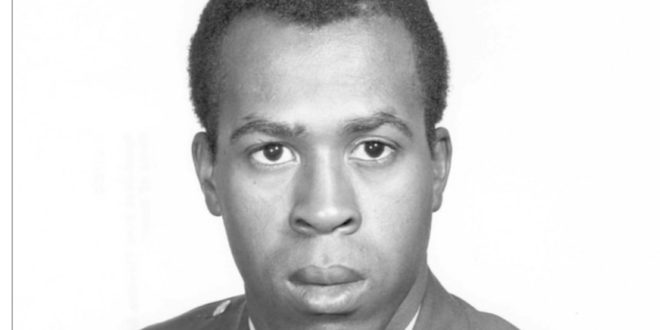

Army Spc. 5th Class Clarence Sasser was a part-time college student when he was drafted into the Army as a medic. He was sent to Vietnam at the height of the war and did his job so fearlessly during battle that he earned the Medal of Honor.

Sasser enrolled at the University of Houston to study chemistry. He eventually switched to part-time so he could work to pay for classes, causing him to become eligible for the draft. So, when his number came up, instead of trying to gain college deferment, he joined the Army in June 1967.

Sasser trained as a medical aidman and knew pretty quickly that he would be going to Vietnam. He arrived in the country in late September 1967 when he was barely 20 years old.

Sasser hadn’t been in Vietnam for more than four months when he was put to the ultimate test as a medic with the 3rd Battalion, 60th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division.

On Jan. 10, 1968, then-Private 1st Class Sasser was with Company A on a reconnaissance mission to the Mekong River Delta to investigate reports of enemy activity. That morning, as about a dozen company helicopters were landing, they suddenly started taking heavy fire from three sides of the landing zone. A well-entrenched enemy using rockets, machine guns and small arms managed to take down 30 American fighters in the first few minutes of the attack.

“I got grazed getting off the helicopter, in the leg,” Sasser said during a Library of Congress Veterans History Project interview in 2001. “[There was] fire all around us. With the helicopter down, there wasn’t any choice. We had to go in.”

Through a hail of gunfire, Sasser ran across an open rice paddy to help his injured comrades. As he helped one soldier to safety, he was wounded again, this time in the left shoulder by fragments of an exploding rocket.

“Shell fragments are something. I’ll never forget how they feel,” Sasser recalled. “The pain sets in later. The initial shock is what you experience, and the searing — shell fragments are hot.”

Sasser ignored his injuries and ran through a barrage of rocket and automatic weapons fire to help two more men before moving on to search for others who were wounded. After suffering two more injuries that immobilized his legs, Sasser dragged himself through the mud to continue his work.

“The best way to get around that day was just simply grabbing the rice sprouts and sliding yourself along. You could move better like that. If you stood up, you were dead,” Sasser said. “The snipers would get you.”

After crawling roughly 100 meters, Sasser treated another soldier before encouraging more men to crawl 200 meters to relative safety. Once there, he treated them over the course of the night. Sasser said if it wasn’t for Air Force close air support dropping bombs to keep the enemy off them, they likely all would have died.

“We laid there that night. All you could hear was guys moaning, calling for their mama,” he remembered. “Listening to them beg all night … It was the toughest thing I’ve ever done.”

Sasser said evacuation helicopters finally came for them around 4 a.m. or 5 a.m. the next day.

“It was a relief. We were out of there, and I was still alive. I was hurting, but I wasn’t in mortal danger,” Sasser said of his feelings at that moment. “I had made it.”

Sasser was treated at a hospital before being evacuated to Japan for further recovery. During his rehabilitation, he helped out at the hospital’s dispensary, and a doctor he’d befriended was able to get him reassigned there instead of returning to Vietnam.

“To this day I thank him,” Sasser said.

It was during that assignment in the latter half of 1968 that he learned that he had earned the Medal of Honor.

“I don’t think what I did was above and beyond. I never have, and for a long time I had a problem with that,” Sasser said. “But finally … a friend helped me reconcile it to the point that it meant, ‘Hey, you did your job.'”

After transferring back to the states,, the nation’s highest honor was presented to him by President Richard M. Nixon during a White House ceremony on March 7, 1969. Two other soldiers, Army Staff Sgt. Joe Hooper and Army Sgt. 1st Class Fred Zabitosky, also received the Medal of Honor that day.

“Probably the greatest thing to me was to be in a room with [Army Maj.] Audie Murphy, [Marine Corps Col. Gregory] Pappy Boyington and [Army Gen.] Jimmy Doolittle,” Sasser said of the ceremony. “These guys I had read about — guys that I’m now in their situation or I’m in their society or their group. That, to me, was something.”

Sasser was discharged from the Army in June of 1969 and returned to his chemistry studies, this time with a scholarship to Texas A&M University. Before finishing, though, he married Ethel Morant and took a job at a petro-chemical refinery near Houston. He worked there for five years before beginning a longtime career with the Department of Veterans Affairs in Houston. He and Ethel had three boys, Ross, Benjamin and Billy.

Over the years, Sasser has given talks to schools and veterans organizations about his experiences. In 2013, he was inducted into Texas A&M’s Medal of Honor Hall of Honor. During his speech, he said how not graduating from the school was one of his biggest regrets. So, in 2014, the school gave him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree.

Interview with Clarence E. Sasser [n.d.]

Unknown interviewer:

Clarence, before we get started, just do me a favor – pronounce your full name.Clarence E. Sasser:

Clarence Eugene Sasser. [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS]Unknown interviewer:

Clarence, tell me a little about your childhood – where you were brought up – what city – your family life – sisters and brothers, mom and dad — leading up to high school.Clarence E. Sasser:

I was born in a small train stop down in South Texas, Southeast Texas, actually – south, south of Houston. I was the 2nd– child, having an older brother – and– a sister–then mom re-married, and I have 4 other siblings – different fathers. We were a farm family, and– as consistent with the early ’50s, along through there, things were tough – things were hard – we always had plenty to eat, because we were farmers – we raised animals – cows – had a milk cow, so I had to milk, milk cows – I do know about that type stuff. We raised– pigs– chickens – the usual farm fare — so we always had plenty to eat – maybe not a lot of money, but we did have – always have plenty of food. As I said, I was the second child out of this group, and– I – would like to think I was a fair student in school – actually I was probably a little bit better than fair – lot better than fair I guess if the truth be known– [LAUGHTER] but– I graduated from an all-black high school – segregated all black high school -which was the times! I probably would not have traded that experience for anything. I graduated high school number four our of – out of 68, which I thought I was pretty fair – pretty fair student. I left high school and– moved into the city of Houston and started attending the University of Houston– I was a– chemistry major, and did pretty well – but again, no money – the monies were–were– wasn’t there, so– and then started to work – of course I had a part time job, but– the mistake [LAUGHS] I – I made was– in the age of student deferments – of dropping to half-time – you know – to work – work a little bit more – and from that point I was drafted. Drafted into the Army. Went to– basic training in Fort Polk, Louisiana — we called it Fort Puke, cause of the red sand and the hills – up and down the hills. And from there I went to the Medical Training Center at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas. Now how I got to be a medic, I have no idea. [LAUGHS] I, I like to think the Army had a rhyme or reason to it, but at any point – I went to– medical training center to be trained there as a medic. A corpsman – we liked to call ourselves combat medics -although a lot of medics weren’t sent into combat, I always knew I would – it’s one of those things you just – you just know. When I was drafted, I had decided, at that point, to take my chances — I could have gone down and enlisted for whatever option I decided I wanted or whatever, but– if you enlisted you had to do longer than the 2 years, depending on what you chose, you had to do either 3 or 4 years – and as I said, I was drafted – my idea was to, to– in so many words, do my time – get out – and get on with life. So I took my chances.Unknown interviewer:

When, when you were in college, so the draft took you right out of school?Clarence E. Sasser:

Yes, sir. Although I was just a half time student, but I was still attending classes and, and making grades.Unknown interviewer:

Were you resentful at all at that time for being drafted?Clarence E. Sasser:

No, not really, because it was a fact of life back then. It was a fact of life– that if you– didn’t have a deferment, then you, you were drafted. I actually sort of embraced it. You know? It was a change in your life. It, it– was common knowledge at that point about the G.I. Bill, so you know, you go – you’re drafted – you go do your time, you get out -you got a little bit more money for school. If you were– if you were– conscientious, you could save a little money and then go on to school! And– I’d like to think that’s what I did.Unknown interviewer:

Was your training – and you went to basic where?Clarence E. Sasser:

Fort Polk, Louisiana – it’s northeastern Louisiana – it does get hot – it does get cold in the wintertime up there – it’s – you know -not like the southern part. It’s almost like North Texas and– South Texas.Unknown interviewer:

Tell me a little about that training.Clarence E. Sasser:

It– was– tough but– at that point, I was–in good physical shape – I was a athlete in high school, and– I liked to think kept myself in good shape. So– the training wasn’t that much or anything – it was, it was drudgery type s– work or– and it– sort of acclimated you because at that time, they were emphasizing with the draft and the, and the war in Vietnam that you know, a lot of us were going. Like, as I said earlier, you know, I didn’t have any doubt that I was not going to [LAUGHS] Vietnam — I knew I was going. Particularly when I was sent to medical training s– center for training as a corpsman — corpsmen were– really necessary and were shall we say used over there — people were dying – corpsmen were dying, were dying so–Unknown interviewer:

Tell me a little about medical training -what’s that like?Clarence E. Sasser:

Well, i– now you would compare – and in fact it was the f– forerunner to paramedics type training that you see people go through now–in fact it ha– just– changed – metamorphosed into emergency treatment — I think it was the beginning of our emergency treatment system that we now enjoy. There were simulated battle casualties that you were– taught and expected to learn to treat – there were plain old preventive medicine type things that you were taught and expect– expected to retain. I like to think I ate it up, cause I’ve, I’ve always been a reader — and– I read in high school – I still read quite a lot, and– I, I like to think I ate it up – it was about the human body – was a lot of teaching about the systems of the body and of course I– like to think I had excelled at that in high school and college. So– to regress a little bit, back to the Army’s choice, I thought it was sort of–unique – neat that the Army had, through the battery of tests had figured out that that was probably what I was best at! And I still think I am.Unknown interviewer:

In those early years, who were kind of the people you looked up to or who were your -admired or heroes?Clarence E. Sasser:

Well, you know, back during that time, hero worship and all of that had just really started – I w– as I said, I read a lot – I read about history and wars — my father was a World War II vet, so I was aware of the military, and, and it was in the– material that I chose to read. I– As far as heroes, of course a high school principal was a guy that had taught my mother – and was well-known in the community, so I, I would – at– this point have to say he was one of the early heroes. My father, for being a World War II veteran, my stepfather for being a, a family man and raising us — to the point of where we were–essen– essentially self-supportive.Unknown interviewer:

Was – religion play an important part in the early years?Clarence E. Sasser:

Yes, religion played a part in almost all black families, and still to this day I, I would certainly like to think it does. We were churchgoers – my stepfather was a deacon in the church – and by virtue of that, the–effect of religion on my life, of course, was– quite a bit.Unknown interviewer:

So being part of the medical unit sort of put all that into perspective, I, I can imagine.Clarence E. Sasser:

I would think so, yes, sir. I would think so.Unknown interviewer:

When you’re in the med– when were you notified that you were going over to country?Clarence E. Sasser:

After graduation from– medical training center, Fort Sam Houston, we all were– given orders to various unit – mine was to– the 90th Replacement Center, Republic of Vietnam.Unknown interviewer:

And what was that like, when you first got over there.Clarence E. Sasser:

Scary. I mean– real scary– to the point of– you know, a good cry and what am I doing over here and– I want my mama and all of that type stuff, you know – of course I’m a– I am a twen– 20 year re– just barely twen–turned 20 years old at that point, but– as a– product of– the ’50s– I had been quite sheltered in the sense of worldly– things. It was a rude awakening – just– just tough -scary.Unknown interviewer:

Well can you talk a little about when you first got there, your first combat experience or the first time you felt someone shooting at you.Clarence E. Sasser:

I think I had been in country probably 3, 4 days – had– gone through the in-country orientation – everyone came in– were assigned to whatever unit– infantry or– whatever unit that y– they assigned you to when you came in to the 90th Replacement Center– we were replacing troops that had rotated back home, or of course, that had been killed. First combat experience — was a night movement, and– quite– scary– hairy, I guess, may be a better word for it– after leaving the replacement center, I think 4 days later, I was– assigned to the 9th Infantry division down in the Mekong Delta – place called Dong Tan [sp?] – a– base camp, large -pretty large size base camp that was part of the– mobile riverine force [sp?] – the n–that unit of the 9th Infantry worked with the Navy – brown– the brown water Navy – the rivers and the– and the– tidal basins down, down there, down in South Vietnam. The first combat experience, you know, was probably a mistake – in that we were moving at night — the base itself was protected by radar — we were moving out in the, in our area of operations, and I guess somehow things got a little confused, and– our own base camp started lobbing mortar fire in on us. Just one of the mistakes that happened – mistakes happen everywhere all the time – but– that was a baptismal – for me. Pretty hair with your own people [LAUGHS] shooting at you. Of course it, it was mortar – so mortar fire – so you know, it wasn’t quite as bad as two units in direct conflict, but– it was bad enough.Unknown interviewer:

Did you have to go in the field and– give some aid that evening?Clarence E. Sasser:

Yes, sir – we had 2 guys hit by, by the – by the– shell fragments – from the mortars that were coming in. One was quite serious and–and– and– quite serious. The other wasn’t -was more or less a flesh wound, but you know the storm – the normal procedure on it – you -you know – stop the bleeding– and then spend your time with the more seriously injured ones. And then we got a dustoff – a Medivac helicopter – we called them dustoffs – in to get him out – well actually get both of ’em out cause they were – although one was real serious, the other one was not. It was probably — pretty close to the most traumatic experience of my life, you know, you got a guy here that’s bleeding to death – and everything – the blood’s– quite– traumatic to– have to deal with it – the blood’s just–just something.Unknown interviewer:

How well were you prepared with the training for it.Clarence E. Sasser:

I think it was – the training was very appropriate – it prepared you for it all, all – the only thing it could not prepare you for was the– trauma– the– the fast-paced-ness that– happen– that occurs when these type injuries are sustained. You just had to keep your head and remember the– lessons you had been taught.Unknown interviewer:

The following day, how– how did you feel about yourself and the competence that you -you were ready for bigger things?Clarence E. Sasser:

Well, I felt quite good, and, and– the guys in my platoon felt quite good about me, and that I liked– I’ve always been a people person – I’ve always– I, I guess been a people person – I always could deal with people – could talk to ’em – could get them to see my way or– shall we say – do things my way. [LAUGHS] So– I’ve always been a, a people person, and that– figured in with it – the guys were–satisfied that they had a good medic — you have to understand the camaraderie that go on– between troops in harm’s way! The doc is the closest thing to ’em. He’s the one that just may save your life, and they treated you as, as such – and I loved it! I loved it, man. [LAUGHS] I mean you know here I am– you know – okay, I’m gonna do what I’m supposed to do for you -but in return, we [LAUGHS]– you know – like -sort of like that type thing.Unknown interviewer:

There was a great deal of respect for the medics.Clarence E. Sasser:

Yes, they do, and rightfully so – rightfully so. In the type situation we were in, the casualties were sometimes massive – the injuries were sometimes m– massive– the casualties were usually plenty. And the guys wanted a medic that would take care of ’em. They, the platoon I went to had, had benefit of another good medic prior to me, and they expected the likewise, so it’s – it’s the sort of thing they tell you about Doc before you who had gone on– to– work in a– evacuation hospital. The rule over there was that if a medic was assigned to an infantry unit, he went – he did 6 months of– call it field duty, and then after 6 months they would bring him back in to a hospital for his last 6 months. Of course it was a 12 month tour over there. And– as I was saying, the guys understood and had enjoyed the benefits of having a, a good medic — I like to think that I was a good medic, because – and, and I thought so then. The– thing with the guys was that if they were hurt, they wanted treatment– as any of us would; and they expected you to treat it! I mean don’t care how heavy the fire was — if he was laying out in, in, in, in danger– and he’s hurt – he expected the medic to come and see what he could do about it — he didn’t care about the medic maybe getting killed coming — he expected– you to come. Wasn’t no such thing as what you see on TV –about it’s too hot out there, I’m not going. Course no one made you go — you made yourself go.Unknown interviewer:

Tell me a little about the battle at– you were awarded for – and what you did.Clarence E. Sasser:

That battle started on – in my mind, even now – back then I thought so – on shaky ground. We had been in battles and combat and all of that, and– we were scheduled as a–backup force, which meant we t– we, we set up camp– we have a easy mission this trip – you know, we’re not beating the bushes – we are stationed there – all you have to do is put out your perimeter and your [guards] in, run a few patrols at night. And what– And we were – we were– scheduled for that. We were 2 days into that –enjoying it too, man [LAUGHS] – when– our company commander got a call, and gave ord–from the battalion commander – gave orders for us to go to this area– and check out– some–movement he had seen from his helicopter. So– we did — we’re loaded up on board – we called them slicks – they were Huey – Huey–helicopter gunships – troop carriers – they had door gunners – door gunner on each side–and– we were loaded up on the helicopters and taken to this– area. We– went into a rice paddy — the movement was in– had been seen in the tree line surrounding this rice paddy. The onliest place you could get the helicopters in was in– the rice paddy. So we go in — you know, I was on probably the 3rd, 4th helicopter — we go in– and the helicopters start taking fire – rockets – up to – thoroughly bad situation. One of the helicopters got hit and plunked down in the water. The water was probably thigh deep with maybe– knee deep mud – close to knee deep -calf-deep mud, let’s say. Rice sticking up over it. Anyway the helicopter’s down – we have probably – I don’t remember – 12, 14 more coming with the rest of the, the company. Company A. We– got off the helicopter – I got grazed getting off the helicopter, in the leg – and everything and– of course – fire all around us. With the helicopter down – and it was -wasn’t any choice – we had to go in – and so we were dumped in the rice paddy. I say “dumped” – that’s – essentially what it was – we were off-loaded in the rice paddy -we never made the tree line until dark had fallen, and we went in probably 10 – 10:15 that morning, and we spent the whole day in the rice– We spent the whole day in the rice paddy. Terrible – people getting killed. And– you know, we were company-strength with – each platoon had a medic – of course y– of course yeah, I knew the other 3 medics and all of that, and we were still, you know -pretty good – we had a pretty good bond as medics, because you were Doc. A lot of times when we were out on missions, and we were re-supplied with c-rations which -the food we had – soon as they busted open a box, the medic got his choice — in return for that, you had to go help him. And everything. Fair game. So– at any rate– the mortars were coming in – snipers were around – guys were yelling Doc– Doc– and of course at this point -there’s no– semblance of platoon-like unity -everything was– the company – just the entire company. I guess to make a long story short, I was the onliest medic that lived. I saw one of ’em take a direct hit– from a mortar. Tough. But– as I said, I had gotten grazed through the leg getting off the helicopter, which was again probably lucky and everything and– I picked up another injury — when I was almost– hit with a– mortar round – that almost just totally sprayed my back, which was– which was probably something that– I engineered because I heard it coming – and– turned my back to it and everything – so it burst probably– 3, 4 feet away from me, and by virtue of my lying down — remember we’re still in the rice paddy — the dampening of the shell fragments– that the water of course does – sort of helped -helped a lot and everything – but I did get sprayed all over the back. And– shell fragments are– something I’ll never forget how they feel. You know– it’s almost no pain – the pain sets in later. The– initial shock is what you experience and the – and the searing of course cause the shell fragments are hot. Man, you could hear ’em all day, boy – they’d come in boom! And then you’d hear Ssss! When it’s just shooting into the water and when it hit the water, you hear it just sizzle, man. So– I guess– unless it hit– a nerve or a blood vessel– it’s just more aggravating than anything, you know? It numbs you – it numbs the spot – it cauterizes the wound where there’s not so much bleeding– it just – it’s just– END TAPE 34 – SIDE A START SIDE BClarence E. Sasser:

I had learned early on that the best way to get around that day was just simply– grabbing the rice sprouts and sliding yourself along -you could move better like that than to try to of course stand up. If you stood up, you were dead. [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS]Clarence E. Sasser:

I had learned early the, the best way to get around was just to grab the rice and drag yourself around. It was a lot quicker than you could move if you were standing up, because of the mud– the water and the mud, and– it was– just easier. It’s the onliest way to get around and still half protect yourself, cause if you stood up, the snipers were getting you. They were g–they were– they would get you. Especially they see your bag — they know that you’re a medic — you know, you kill a medic, a lot of people probably would die – it was – it was the rationale. So– anyway, here I am just pulling myself around and everything and going to guys–doing the best I can – I could. [PAUSE] Anyway, doing the best I could – that’s all -anyone could ask.Unknown interviewer:

Did you pick up a weapon and fight?Clarence E. Sasser:

No more than just playing, in the sense of playing – I did– as I said, my – I, I believed firmly that my job was to care for the guys. My job was to care for the guys -to treat ’em– to– maybe get ’em to– carry on– and in fact what I remember telling one guy [LAUGHS] was– you men take your – take your weapon – take your weapon – after I finished putting a bandage on– take your weapon – let’s try to get out of here. I felt that was my job – I didn’t think that picking up a weapon would help our – the cause – my job was, was to treat ’em – to at least let ’em know that Doc was around, and would come see if they called.Unknown interviewer:

Okay. [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS] Night came.Clarence E. Sasser:

It’s tough. Was tough. It wasn’t so much the, the enemy activity, man – it was laying there listening to your guys call for their mama! And you can’t do anything! It’s tough. It wasn’t so much enemy activity or shots or things of that nature – it was– was just listening to ’em beg all night! And then you wouldn’t hear him any more – you’d know he died! It was tough – it’s the toughest thing I’ve ever done. Excuse me. It was tough. It’s tough as night. [LAUGHS] I want to say the toughest night in the history of man, but I’m sure other people have had nights worse. But that doesn’t make it any easier. I mean you lay – we laid there that night– we laid there that night — all you could hear was guys moaning. Calling for their mama –help me — there’s nothing I could do! Some body [and I] had been hurt, again, had been–probably true to my– [LAUGHS] probably true to my parents– thoughts [LAUGHS] had had a bullet to bounce off my head and everything –so– probably true to their thoughts about being hard-headed and all of that but– it was just tough.Unknown interviewer:

When did they come and get you out?Clarence E. Sasser:

They got us out– what – I’m – what we country boys call ‘fore day — the next morning — I guess it must have been about 4 or 5 o’clock that morning before they tested the– area -now understand, by now– some of us have gotten barely inside the tree line and everything, but there’s no– actual ground they could bring a helicopter in – it’s all rice paddy. So I guess about 4 – 4 o’clock that morning they tested and came into the area – and–with the chopper — they came into the area with the chopper and didn’t get very much fire – and then I guess they decided they could come in. We had spent the night being [LAUGHS] – looked over by the– phantom Air Force – phantom pilots were dropping napalm in the tree line and all of that – to keep ’em off of us– our artillery had– in the sense of war, walked up to us and then skipped over us and walked on, and– had– essentially kept ’em off of us all night or we all would have died. Probably– I have reports at home – I went into the after-action [battles ?]– oh–probably th– three years ago and pulled up the ac– the reports and, and everything. Those reports show probably 75, 80 percent casualties – of a company – a company of about 110 – 120 guys — maybe 15 of ’em — had noth– no scratches – whole bunch of inj–injured – probably 40 dead. I mean a real s–a real– a real battle man, with people dying all night. People– [it’s loss].Unknown interviewer:

I’m going to move on, unless you want to go back for something.Unknown interviewer:

If I could — how many – when you went in on this mission – you went in, in the morning -how many people went in – number of helicopters you said – how many people?Clarence E. Sasser:

We were, we were a slightly under-strength company – probably 115 – 120 guys. And we were – we were loaded up on the slicks – the helicopters – and it was 12, 14 helicopters that came in, picked up us and took us. We were a cor– a company strength.Unknown interviewer:

And your citation – it says […?…]. You actually ran repeatedly–Unknown interviewer:

No, he’s talking to me – you’re – [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS]Unknown interviewer:

I’m reading his citation, and it just amazes me that you ran – you – it sounds like you actually got up and ran across this rice paddy – I mean you’ve described for us – are you operating on instinct – is it just you’re trained – is it–Clarence E. Sasser:

It’s training! It was my job! I mean– it was my job. Guy would ha– call Medic, and–you know — you would go to him. And– in the initial stages of the battle, you could – you could– run– use the levees, but then the snipers moved in, and then you couldn’t — you just couldn’t — that’s when I started using the grass, and– but in the initial stages of the battle, getting off the helicopter– guys were – guys were just dying.Unknown interviewer:

Were you afraid? It’s interesting when you answer it’s total focus was on the guys.Clarence E. Sasser:

I wa– looking back, I was – I wa– I’m not going to sit here and say I wasn’t afraid -you know? Of course you were afraid! You were– afraid of getting killed! But– these were my guys — okay? As I, as I mentioned earlier, you know, you were Doc. You were afforded a place within their – within their ranks! and they looked out for you — your job was to look out for them. When they call – when they holler Medic or Doc — your job was to go! Nothing more! Without fear of– your life or– anything of that sort — it was your job!Unknown interviewer:

When you – the following day when you were taken out – you went to the hospital – I’m assuming at that point.Clarence E. Sasser:

Yes, sir.Unknown interviewer:

Tell me about that – what was that like, being – instead of treating people, being treated?Clarence E. Sasser:

Well, it was a relief [LAUGHS] – it was a relief — we were out of there, and I was still alive. I was hurt, but I wasn’t in mortal danger — I was hurt – I knew me – I knew I would heal and I would heal fairly quickly. I had no artery or nerve involvement with my injuries or anything other than the, the head injury. And– when – we were just alive. I’d made it, man! I made it. We were– taken to evac–evacuation hospital where, where they–assessed your injuries — I, I guess what you call it — in the medical field now where they – triage you – assess your injuries and– see who was what or what or– and everything. And then the repair work began – repair work of course was– debris-ing the, the wounds -removing what shrapnel you c–you could. The large pieces were taken out; the smaller pieces were just left. Probably do more damage trying to get them out than what they would do if they just stayed. But it was a relief to finally get to the evac-hospital and to know that you were, basically, okay – basically okay. It was a feeling of relief.Unknown interviewer:

Did you feel you were going to go home at that point?Clarence E. Sasser:

No, I didn’t, because I – as I said, I, I knew I had no artery or nerve in–involvement; my, my injuries other than my head we– were basically flesh wounds, primarily from, from shrapnel, a couple of gunshot wounds were in, in – the one in the leg getting off the helicopter and the– the one to the head, you know, headaches, but other than that, you know, no problem. Didn’t think I was coming back home, and in fact, I did not. What had happened — we had stumbled into – and in use the word literally – stumbled – into the – a buildup of a– NVA-Viet Cong base camp for Tet that started– shortly thereafter. And, of course, as I said, we were chopped up, but I was okay. I was okay.Unknown interviewer:

So how much longer did you stay over before you were sent home.Clarence E. Sasser:

I– actually – I was in the hospital when Tet began, and they started clearing the hospitals for casualties coming in, so I was transferred to– the Army Hospital in Zama [sp?], Japan for further recovery, and after recovery–rehabilitation – a–again, I had– flesh– I had flesh wounds and everything, which healed fair– relatively quickly, but I wasn’t – at the point of Tet, I wasn’t ready for – to go back to duty, so they transferred me to Japan for further rehabilitation. I was in Japan in the hospital and then I started undergoing rehabilitation. I was finally released from the hospital and sent to a medical holding company, which is where they would rehabilitate you [to] the Army daily dozen – the exercises and things to rebuild your, your muscles and things, and while there, you know, [LAUGHS] probably — it’s sort of funny to me now and everything, but being industrious young men, we were at the holding company – everybody there had been injured in some way, shape, fashion or form and would– do the – the exercises, but then go to the dispensary for any treatment they needed on their injuries or illness or whatever. So being a medic, I started hanging out at the dispensary during my off time — I’d do the exercises and everything which were in the morning and early afternoon, and in the time between, I’d go hang out at the dispensary –I would actually help ’em! So– an understanding doctor needed another medic, and he got me re-assigned there, so I didn’t go back, or I would have gone back to my unit in Vietnam, which I – to this day I thank him.Unknown interviewer:

When did you hear about that they were going to put you in for the medal?Clarence E. Sasser:

After I had recovered, and the understanding doctor had– gotten me re-assigned – I don’t know what he did or how he pulled strings, but they did need medics there — I was called into his office – he was of course the offic–officer in charge of the dispensary, where by now I had been re-assigned. This was probably in– August – somewhere along there – and told me that– told me that the commanding general want–wants to see me. What?! What’d I do? I haven’t done anything, doc. He said oh, you’ll like it – it’s all right – it’s all right. So – okay, so he takes me over to the commanding general, and I was informed that– the– Department of Defense had decided to award me a Medal of Honor. Oh, okay. You know? Fine with me. I of course realized the significance of it and all of that, but – okay, it’s fine with me. But that they were — this was probably September – somewhere along there – September or October as I think about it – and– you know, he told me that it had been approved but they had not decided when to award it. This was in ’68– and then President Johnson had of course said he was not running for re-election, so they wanted to see who was going to do it – who was going to win the election -the general election – and then decide when they would award it. Fine with me – and everything. So word finally came down shortly after inauguration and of course Mr. Nixon had won the– election, and that we– I was to be transferred back to– the States for pres–presentation of the Medal of Honor. We were a group of 3, and we were his first–awardees– at that time, of course, the war was in full blast, and they hadn’t yet come to the point of – where withdrawal – we were withdrawing from over there. The– the– Paris Peace Talks were under way, and of course all the guys were – well, they had been under way even when I was out in the field then, you know – we sometimes talked among ourselves, and we’d get a little bit perturbed like that because, you know, we felt we had enough guys there – we could start at one end – shoulder to shoulder and clear out the damn country and then be back home by Christmas. It was just a general feeling among the guys. There was not any protesting going on over there. There were no hassles between races in Vietnam at this point as – subsequent – what subsequently happened over there. The dope was not– prevalent as what subsequently happened – all of these type things, in my mind now, were signs of discontent. They were not there then -everyone was– a hundred percent behind the war, but we just need to take care of this and get out – we got enough guys and enough technology — whatever we need, where we could start at one end and walk to the other end of the country and be through with it! But– it was quite something. I remember write home to my mother and telling my mother and stepfather that – they just told me I was going to be awarded the highest medal– and everything and that– they don’t know when, but at some point I’ll be home. Cause at this point now, I had been gone– I had left short–shortly after my birthday in September and by now we are– into October -so I’d been gone 13, 14 months already and everything but– I didn’t have a problem with that. I was not over there any more.Unknown interviewer:

Tell me a little about the ceremony – the first medals that Nixon was presenting – how’d that go?Clarence E. Sasser:

It, it, it went quite well. It was really an experience from my background – of course -you know – poor farm family and everything -my moth– my mother and sisters were flown up to D.C. and of course this was the best – this was I guess the best thing that ever happened to ’em and everything. But– it was quite something that when there were 3 of us, there was– all 3 were Army -Fred Zabatovski [sp?], Joel Hooper [sp?], and myself. We enjoyed it; tremendously enjoyed it. Of course you have family there for the ceremonies in the, in the White House and all of that and– press conference with all of the generals around and all of that then. It’s just a unique something. I might add that the other two gentlemen are deceased now. But we were real good friends -all the 3 of us – I mean it was a bond forged– there in the White House.Unknown interviewer:

What’s that medal mean to you?Clarence E. Sasser:

Simply that I did my job. That’s it. It means nothing more to me — well it means a little bit more in, in the sense of other aesthetic things, but it means I did my job. It’s confirmation to me that I did my job, and that’s how I had to deal with it, because it was my job – I don’t think what I did was above and beyond! I never have. And for a long time I had a problem with that. I had a problem with why they – why all of this – I just did my job! My job was to take care of my guys. That’s it! But finally–you know — I reconciled – a friend helped reconcile it to the point that – hey – it means you did your job – that’s it. That’s what it means to me. And the other aesthetic values – it means that you know – it, it– it sort of means that stuff like this — the– this interview and everything for posterity’s sake– that– a small deed on my behalf will live forever in the chronicles of man – chronicles of war -which will always be here. War, to me, is the– result of when people can’t agree. There will always be some type or form of war, and, and it means that, you know, a small deed will be remembered. It has– afforded me probab– maybe – I say maybe – because I’m still not sure about this point, but it has afforded me a better life than I probably would have had. It has certainly– raised my level of– understanding about life, the world, the USA, things like that.Unknown interviewer:

Is there– [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS] END TAPE 34 – SIDE B START TAPE 35 – SIDE AUnknown interviewer:

Talk about a lot. [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS] What is the value – I don’t know if you ever speak to children – what do you think they should take away from hearing your story – the story of other people – with these amazing […?…] terrible situation – a lot of people couldn’t stand up to.Clarence E. Sasser:

I, I do talk to schools and– and– a lot of veterans’ organizations – I do some active duty talks or– whatever you want to call them. But I always try to tell kids that–number one is to do– what you’re supposed to. That once you do what you’re supposed to you get a good, sweet, warm [TAPS CHEST?] fuzzy feeling right here. You know that you have done– your job. I–[LAUGHS] am not the most prolific, I guess shall we call them speaker or interview — I select what I do very carefully, and I have other interests other than this and, and whenever you – you do it – you tend to–dredge up memories, so I’m not the most prolific — you won’t find a lot of interviews from me. In fact, I am probably one of the more reluctant ones that the– historical society [LAUGHS] know of. I do– sign autographs, but – although I’m not that prolific even doing that. It dredges up memories, and these are memories that are– that you deal with better if they’re not on the forefront of your mind.Unknown interviewer:

Is there anything that I haven’t asked you, you want to talk about?Clarence E. Sasser:

Well, you, you have asked about what the medal means to me – it means what I said – it means I did my job. It– is sometimes heavy – it’s a heavy something to wear. It’s easy to strap it on or button it on or however you want -choose to phrase it – but– it– requires certain things of you. Some of those things are to your benefit. One of the guys that– I knew shortly after presentation – or this was during – back during the early ’70s – was another black guy — Dwight Jones. Unfortunate case and somewhere down the line you guys read up on it and see what happened to Dwight. It sort of forces you to go the straight and narrow. I mean [LAUGHS] you don’t want to be in the newspaper, Medal of Honor recipient robs a bank or caught with dope, so it, it, it sort of makes you live up to it, and that’s not – that’s not a bad thing in the sense of things that you – you haven’t asked– probably the greatest thing to me– was to be in a room with Audie Murphy, Pappy Boyington, Jimmy Doolittle — these guys – guys I had read about. Guys that I’m now in their situation or I’m in their society or their group — now that, to me, was something. It’s — and I’m going to put it like, like the TV folks say — here’s a little old country boy – black country boy — that’s– in this -in this– group! Now that, to me, was something! To meet – Admiral Stockdale — to meet – Audie Murphy — the guys I’ve mentioned – the Baa Baa Black Sheep Pappy Boyington and all of that. Just to rub elbows with them and to – for someone to think – hey, man – he’s good as they are! Nowhere near– nowhere near good as they are. But it was really something to me to be in that group. And it still– some of the guys– guys that– personally I never would compare myself to, but by virtue of the Medal I’m included in with them. I– and I don’t make a point of it – but– you know, being one of the two – only two black guys alive now– is a – is indeed a burden–it is a burden cause things like this where I’m – you know, might not ever would do– I feel I have to do, just simply because– that point. A lot of places we go – you, you look around the crowd, and there are a few black people out there and everything – and, and I know were I not there, they would wonder where are the black — aren’t there any black guys in this group?! So by virtue of that, I feel like I have to go, and I do– go. Although considerably less than probably what I should but– I try to balance it with my needs– and my need specifically not to be reminded of this stuff all the time. I have some friends at home– that are– most of us are, you know, served in the military back during this time or the time of draft -they clean out the small towns – for whatever reason – good, bad, indifferent – but they clean them out – most of us served. So I had some friends around there, man, and they – they think I’m good. [LAUGHS] But–again, it’s a matter of perception. I– enjoy being a Medal of Honor recipient to the extent– my uses– but that – that may sound selfish, but it’s — as I said earlier, it’s a heavy burden to wear it, and to wear it well, which I like to think I do.Unknown interviewer:

One more question — what do you think it means to the country?Clarence E. Sasser:

Yeah, I never have really thought about that. But we are a country of, of heroes — we–believe in heroes– we– need heroes to– rear our young – young ones. I think it means a lot to the coun–country that I am who I am. As a symbol– and that segues into another, another comment — I have sons, man. I have 3 sons. And I’m intensely proud of them to be young black kids in nowadays – it’s not easy. I tell them every day – every time I see ’em — and we are very close — I tell them every time I see ’em that I’m proud of them. And through raising them, no policeman has ever come to my house talking about what my sons have done. To me, that is my crowning achievement beyond the medal — is to raise 3 young black boys that are not a burden on society. To me, that I feel is my crowning achievement. They know about it – they know dad don’t talk about it -but every once in a while he’ll get around his friends, and we listen in, and they’d be talking about it, you know, cause all of ’em served and all – all the guys I mentioned previously served in Vietnam — and they know what it’s like. So they’ll hear us talking or we’ll be sitting around doing 12 — we call them 12 ounce curls – and– you know, you get to talking about stuff you saw over there and they, they listen and everything, but– they are good kids. Thank you.Unknown interviewer:

Clarence, when you read that citation, do you ever wonder where you got the courage to do this – to not just do your job but to do– to put others above yourself – service above self maybe some people say is–Clarence E. Sasser:

Well–Unknown interviewer:

— does it come from your background that’s–Clarence E. Sasser:

I think – as I said earlier, I’m, I’m – I’ve always been a people person, and– in being that – still certain things you have to [build] and that’s – I’ve never actually thought about it– other than I’ve always known I was a people person– I’m not saying a leader, although I think I’m that too but–I’m not saying a leader — I was a people person. And this is some of the things that I taught -I like to think that I taught my sons! – is that you walk into a group – and pretty soon the group gravitates to you — because – not necessarily who you are – but they get to feeling that you’ll do whatever it takes– I never actually thought about it. Anything other than that.Unknown interviewer:

I think we’ll let this man go before– [OFF-MIKE COMMENTS]Unknown interviewer:

Tell me a little bit about the battle that you were awarded for and what you did.Clarence E. Sasser:

That battle started on – in my mind, even now – back then I thought so – on, on shaky ground — we had been in– battles and combat and all of that, and we were scheduled as a–backup force, which meant we t– we set up camp– we have a easy mission this trip, you know, we’re not beating the bushes – we’re stationed there – all you have to do is put out your perimeter and your guards and– run a few patrols at night. And w– and we were – we were scheduled for that. We were two days into that — enjoying it too, man [LAUGHS] — when our company commander got a call, and gave ord– from the battalion commander – gave orders for us to go to this area and check out some– movement he had seen from his helicopter. So, we did. We were loaded up on board — we called them slicks – you know, they were Huey– Huey– helicopter gunships – troop carriers, they had door gunners – door gunner on each side. And– we were loaded up on the helicopters and taken to this– area. We– went into a rice paddy — the movement was in– had been seen in the tree line surrounding this rice paddy. The onliest place you could get the helicopters in was in– the rice paddy. So we go in — you know, I was on probably the 3rd, 4th helicopter — we go in and the helicopters start taking fire – rockets – up to – thoroughly bad situation. One of the helicopters got hit and plunked down in the water. The water was probably thigh deep with maybe– knee-deep mud – close to knee deep -calf-deep mud, let’s say. Rice sticking up over it. Anyway the helicopter’s down – we have probably – I, I don’t remember – 12, 14 more coming with the rest of the, the company. Company A. We– got off the helicopter – I got grazed getting off the helicopter, in the leg – and everything and– of course – fire all around us. With the helicopter down – and it was -wasn’t any choice – we had to go in – and so we were dumped in the rice paddy. I say “dumped” – that’s – essentially what it was – we were off-loaded in the rice paddy -we never made the tree line until dark had fallen, and we went in probably 10 – 10:15 that morning, and we spent the whole day in the rice– We spent the whole day in the rice paddy. Terrible – people getting killed. And– you know, we were company-strength with – each platoon had a medic – of course, of course yeah, I knew the other 3 medics and all of that, and we were still, you know -pretty good – we had a pretty good bond as medics, because you were Doc. A lot of times when we were out on missions, and we were re-supplied with C-rations which -the food we had– soon as they busted open a box, the medic got his choice — in return for that, you had to go help him. And everything. Fair game. So– at any rate– the mortars were coming in, snipers were around – guys were yelling Doc–Doc– and, of course, at this point – there’s no– semblance of platoon-like unity -everything was– the company – just the entire company. I guess to make a long story short, I was the onliest medic that lived. I saw one of ’em take a direct hit– from a mortar. Tough. But– as I said, I had gotten grazed through the leg getting off the helicopter, which it was again probably lucky and everything and–I picked up another injury — when I was almost– hit with a– mortar round that almost just totally sprayed my back, which was–which was probably something that– I engineered because I heard it coming – and–turned my back to it and everything – so it burst probably– 3, 4 feet away from me, and by virtue of my lying down — remember, we’re still in the rice paddy — the dampening of the shell fragments– that the water of course does – sort of helped – helped a lot and everything – but I did get sprayed all over the back. And– shell fragments are– something I’ll never forget how they feel. You know– it’s almost no pain – the pain sets in later. The– initial shock is what you experience and the – and the searing cause of course the shell fragments are hot. Man, you could hear ’em all day, boy – they’d come in boom! And then you’d hear Ssss! When it’s just shooting into the water and when it hit the water, you hear it just sizzle, man. So I guess – unless it hit a, a nerve or a blood vessel, it’s just more aggravating than anything, you know – it numbs you – it numbs the spot – it cauterizes the wound where there’s not so much bleeding– it’s just, it’s just– sort of numbs you. I had– [End of Interview]

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers