In the early morning hours of February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine with tanks and mechanized columns. Simultaneously, it launched missile and air strikes in what Russian President Vladimir Putin said was a “special military operation.” Two years later, Ukrainians who survived the invasion recall their experiences, collected by Soldier of Fortune and RFE/RL’s Amos Chapple. Here are their words.

Anatoly Mikula

I was in Mariupol with my wife Dima who was in labor. This was to the west of Mariupol. Her time was close, the baby was about to come. Then came a shock. We expected something to happen from Russia, but what? In the middle of the childbirth, it happened. I learned from Telegram, the attack was on. It was happening right now.

My Dima looked at me. I am a soldier. She knows who I am. “Go,” she said. “Go now. Join the fight. Push these bastards back from our country.”

READ MORE: “Explosive Traps:” Hunting for Russian Mines and Shells Inside Ukraine

I refused to go. I could not leave her like this. I could not leave our baby. It was our only argument we ever had. Our little baby solved the argument for us. He suddenly came out very fast! I thankfully had time with both of them, my treasures. And then I knew more than ever what I needed to protect. I went to fight. Two years later, everyone is fine. We have spent a lot of time apart. In our hearts we are together. No matter what happens, we are together.

Tatiana Ruda

I will never forget that terrible day. It was so early! All of us woke up to text messages, phone calls, knocks on the door. This horrible thing was happening. I had to decide what to do. I am in Kyiv. I have a car. What could I do? I could help people who had no way to leave.

I got as many people as I could fit in my car, and we joined the biggest traffic jam I have experienced in my life. Thank God we made it. We did not run out of gas, one of life’s little miracles.

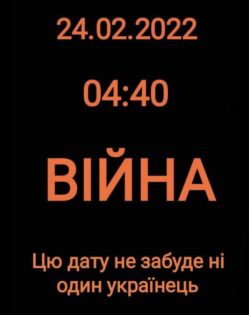

The time of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Later, I brought food and supplies to the front. I brought water. I collected so many bandages, and as much peroxide as I could find. I gave those to our soldiers. On my return trips, I brought children and animals away from the fighting. What else could I do?

I haven’t stopped. I will do this until it’s over or until they kill me.

The following stories were compiled by Amos Chapple.

Tymur Pliushch

The invasion did not come as a total surprise for me.

The situation had already become very tense [in the Luhansk region] a week before the invasion. The number of shellings had increased dramatically and the enemy had begun to use heavy weapons. I still hoped for the best, but at the same time I knew that whatever was about to happen I would be involved in, because I was at the front — or “demarcation line” as it was called before February 24.

I especially remember the night 24 hours before the invasion. Enemy forces fired volleys of Grad rockets at the Pervomaysk-Lysychansk road that connected us with the areas in the rear. I barely slept that night. l was a member of an infantry fighting vehicle crew tasked with covering our frontline positions. I woke up from every noise and mentally went over and over all the actions I needed to take in case of a “red alert.”

The next night, from February 23-24, was actually quite calm. I only learned that a full-scale invasion had started from Telegram, at around 7 or 8 a.m.

Perhaps this sounds strange, but my first reaction when I knew the invasion was under way was to let out a deep breath. As I explained above, I had lived for a long time with the unbearable tension of knowing that something was going to happen without knowing what. And then it was happening.

I knew that I was where I should be. I just had to perform my duties.

At the same time, there was also a sense of bitterness about unfinished plans. I hadn’t yet graduated from university or met all the acquaintances I wanted to make.

The day of the 24th is a bit of a blur. At around 10 a.m. that day, we got an order to change our location, then were essentially “on hold” for the rest for the day.

I remember two things very clearly. First was an object flying overhead. I still have no idea what it was — an aircraft or a missile — and whether it was ours or Russian, but the noise immediately made me dive for cover.

The other thing that stays with me from that day was the cold. At the position we were sent to there were empty apartment blocks that had been abandoned since the 2000s. It was the typical landscape of a depressed mining town in eastern Ukraine — shattered windows, mountains of garbage, and cold that sunk right into your bones. Through the first night of that endless February I didn’t sleep at all.

And then came the war.

Vladislav Bily

The 22-year-old lieutenant was born in the western Ukrainian town of Stary Sambor and died on the outskirts of Popasna.

During a brief interview as he stood outside his fortified position in December 2021, he told RFE/RL: “If a Russian guy comes along and wants to drink some vodka and party, that’s fine. But if he comes to my home with weapons, I’ll kill him.”

In reference to the Holodomor (the starvation of millions in Ukraine in the 1930s under Soviet leader Josef Stalin), Bily spoke about his decision to fight, more than 1,000 kilometers from his home:

“If we don’t come here to the front now, we will die back in our houses later. There’s a Ukrainian saying: ‘He who does not defend his family in peacetime will eat his children in times of trouble.'”

The young lieutenant commanded an isolated military outpost just a few hundred meters from Russia-backed separatist positions. He was injured in the first days of the invasion, then returned to the front. He was reportedly killed in action on March 11, 2022, amid a hail of Grad, howitzer, and tank fire from advancing Russian troops.

His body was never recovered.

Iryna Trubnikova

At 4 a.m. on the morning of the 24th, there was a knock on the door.

We had been living in Kyiv for less than a month. My husband was studying at the National Defense University of Ukraine, and I had joined him in the capital while on maternity leave from the army.

We opened the door to a military serviceman in uniform. He told us to get up because Russia had started a full-scale invasion. Then we heard the first booms of explosions in Kyiv’s Brovary district. It was a shocking sequence of events to wake up to.

I started calling my relatives. There was nothing on the television news yet. My relatives were asleep and didn’t pick up the phone. I ran to the store, but there were only empty shelves.

By the time dawn broke, the military was at full combat readiness. A lot of armored vehicles were driving along the streets to the posts that were just beginning to form. I packed my things and left with my child to drive to Lviv, while my husband and his fellow soldiers remained to defend Kyiv.

The two-lane road toward Lviv became five lanes. There were incredible traffic jams. Some cars even drove off the road on either side. Above the highway outside Kyiv, warplanes were roaring overhead, and we didn’t know whether they were ours or not. My husband was telling me the situation in the capital: They had gathered, geared up, and were patrolling their area in an armored car.

I joined a convoy of cars with families of soldiers who studied at the Defense University. We drove in three vehicles full of women and children. We let each other know about stops and changes of the route by phone in WhatsApp. Instead of the usual five hours, we drove for 24 hours to get to Lviv, exhausted and scared.

At that time, no one knew that a full-scale war would affect everywhere, not only the capital.

Photojournalist Andriy Dubchak

I was in a hotel in Syevyerodonetsk, in the Luhansk region, with the encouraging name Mir, meaning “peace” in the Russian language. Around 4 a.m., my wife, Liza, called me from Kharkiv. She was shouting into the phone: “War! We are being fired at!” This was the first I knew of the full-scale invasion.

I knew it was coming. In the week before February 24, 2022, I came under fire twice, and the intensity of those shellings exceeded anything that had come before. But I had not anticipated the scale of the invasion.

When my travel companions started banging on my door saying, “War! War! What are we doing!?” I was ready to go, with enough caffeine in my blood for action. You could see Ukrainian equipment and troops moving everywhere. The military openly said that they were preparing for a guerrilla war after the occupation of the territory we were standing in.

We were thinking of going to Mariupol but first drove to Kramatorsk to avoid the potential traffic jams in Syevyerodonetsk.

Everyone was on their phones, constantly sending and receiving information.

And then came news about an 80-kilometer-long column of Russian military equipment moving toward Kyiv. I had never imagined the Russian Army would invade the Kyiv region from Belarus.

That news came as a shock. My three cats, relatives, and friends were in the capital. The battle for Kyiv was key at that time in the war. We decided to head to Dnipro, then onwards to Kyiv.

On the way, we stopped at a base to see volunteer medics from the Hospitallers medical battalion who were packing their ambulances for departure to the front. One of the doctors, Yuriy Skrebets, answered my question about what lay ahead:

“We will win. There’s no question,” he told me. “We will win. We just don’t know what the cost will be.”

Tears came to my eyes as the full meaning of those words sunk in.

Kyiv was empty.

Everyone and everything around me was unprepared for war.

I worried about my family and tried to convince everyone to leave the city. I read the news and listened to rumors, and honestly I thought the city had no chance to survive.

I wanted to show everything to the world. Although it was terrifying, this was the beginning of what would be a savage war for the survival of my country.

And I realized that many people I knew would die.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers