by Robert Coalson

“Wagner is a cruel fellow,” a Wagner officer told RFE/RL in 2018, speaking of senior mercenary field commander Dmitry Utkin, whose call sign was Wagner. “He’s no fool.”

When a private jet that Russian aviation authorities said was carrying Wagner head Yevgeny Prigozhin crashed on August 23 en route from Moscow to St. Petersburg, Utkin’s name was also on the passenger list. All 10 people aboard the plane were killed, Russian authorities said.

The Telegram channel VChK-OGPU, which is believed to be connected with Russian security services, reported that Utkin, described as Wagner’s “military commander and head of training” and as “Prigozhin’s right hand,” had been killed in the crash along with Prigozhin.

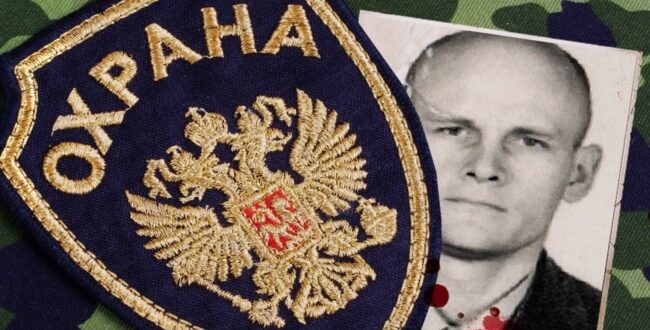

Nazi Tattoos

Dmitry Utkin was born in 1970 in the Urals region industrial city of Asbest. In early childhood, Utkin and his mother moved to the village of Smoline in central Ukraine. After graduating from high school, he entered a military academy in Leningrad — the hometown of Prigozhin and President Vladimir Putin, now called St. Petersburg — from which he was recruited into the special forces of Russian military intelligence, known as the GRU.

He served in the GRU from 1993 until 2013, fighting in both wars in Chechnya and rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

According to numerous accounts by journalists and Wagner fighters, Utkin was enamored of the aesthetics and ideology of Nazi Germany. Photographs of him have appeared showing Nazi tattoos on his chest and shoulders. He adopted the nom de guerre Wagner after Richard Wagner, the 19th-century composer who was a favorite of Adolf Hitler’s. He also reportedly practiced a modern form of Slavic paganism called Rodnovery.

In 2013, Utkin began working for the ostensibly private Moran Security Group, a company created by Russian military veterans to provide security, muscle, and military training around the world. The company specialized in combating piracy at sea.

Around the same time, two mercenaries tied to Moran created a Hong Kong-registered group called Slavonic Corps Ltd. to recruit Russians to fight in Syria and provide security for the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Utkin served with the Slavonic Corps, which suffered defeats in battles with Syrian militants. After a battle in which several Slavonic Corps mercenaries were wounded, the Russian military evacuated them to Russia. The two Moran mercenaries who founded the group were detained in Russia by the Federal Security Service (FSB) for illegal mercenary activity.

‘Deniable Decoy’

Utkin immediately formed his own mercenary group, Wagner, using his own nom de guerre as the name. He and other Wagner mercenaries were spotted in Ukraine’s Crimea region during the Russian seizure of the Black Sea peninsula in early 2014. Later, they fought alongside Russian-backed separatists in parts of Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

According to the open-source investigations group Bellingcat, in 2020, Utkin “was not in the driver’s seat” in the formation of Wagner but rather was used as a figurehead and “deniable decoy” to mask Russian-government involvement.

Utkin and his Wagner fighters returned to Syria in 2015 after a period of intense training in Russia’s southern Krasnodar region. The group suffered heavy casualties in an offensive in and around Palmyra in March 2016. The Russian government continued to deny it was connected with the mercenaries, although they coordinated closely with the Russian military and were regularly transported on Russian military aircraft.

The connection between the Kremlin and the mercenaries became harder to deny when Utkin was seen attending a lavish Kremlin event in December 2016. He was photographed with President Vladimir Putin wearing his Order of Courage decoration. When asked what Utkin had been decorated for, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said only: “Usually they give it for courage.”

According to some reports, Utkin commanded the Wagner forces during the group’s ill-fated attempted mutiny in June, exactly two months before the plane crash. At the time, Igor Girkin, a former Russian intelligence officer who in 2014-15 played a prominent role in anti-Kyiv violence in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas, wrote: “I am not acquainted with Utkin’s moral qualities, but he definitely has operational talent that he has honed over many years.”

Decapitated?

In July 2022, retired Ukrainian intelligence officer Viktor Kelyuk said the Wagner group was attempting a “rebranding,” creating a new “private military company” called Liga. Kelyuk told Current Time that the goal of Liga seemed to be to filter out the less-qualified Wagner fighters, including convicts, and create a unit “to carry out more difficult and important tasks.”

Utkin, Kelyuk said, was based almost exclusively at the Wagner training center in Russia’s Rostov region, which borders Ukraine, working on this project.

“He is not really participating in any combat actions,” Kelyuk said.

The deaths of Prigozhin and Utkin, if they are confirmed, would be a “defining moment” for Wagner and its activities in Africa and elsewhere, said journalist Ilya Rozhdestvensky of the Dossier Center investigative group, who described Utkin as the group’s “direct field commander.”

“That would decapitate the Wagner fighters and leave them de facto without leadership,” Rozhdestvensky told Current Time on August 23. “They would have no one to swear loyalty to and would have to seek new employers. In such a case, the Defense Ministry is the most likely candidate.”

“Death is not the end,” Utkin said in an undated conversation with Prigozhin that has been posted on the Internet. “It is just the beginning of something else.”

Robert Coalson is a senior correspondent for RFE/RL who covers Russia, the Balkans, and Eastern Europe. Follow him on X at [email protected]

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers