by Martin Kufus

Editor’s note: Author Martin Kufus has published Plow the Dirt but Watch the Sky, a memoir of his many adventures. Herewith some excerpts from the chapter where some unusual requests come his way while he is an editor at Soldier of Fortune.

The phone call had come in early that morning, probably from Woody Creek, Colorado. The voice on the answering machine in my Boulder office was monotone, a mumble: “Uh … Marty, this is Hunter Thompson. I got your letter and copy of Soldier of Fortune.” The gist of the message was he was interested in my proposal—that we pay him to write a 600–700-word national-political essay for the magazine—but he would need a few things up front to keep the conversation going.

“I don’t want to say anything more over the phone.” Thompson said that he would send me a letter.

Click.

After rewinding the tape, I walked down the hallway and asked some colleagues to come listen. I played the message.

One of the editors, Tom Reisinger, shook his head and laughed. “I dunno, amigo,” he said. “You might get Thompson to write something, but [then-publisher] Brown doesn’t like him and could kill the idea.”

Tom said he heard years earlier this big-name writer had obtained press credentials to cover a Soldier of Fortune Convention and Expo in Las Vegas…. But instead, “gonzo journalist” Hunter S. Thompson had created a ruckus when he got caught smoking a joint in the men’s room at the Convention Center….

Still … my idea to recruit Thompson for a one-shot gig had merit, I thought. It was 1997. The magazine was 22 years old and its newsstand sales and subscriptions were dropping. In its heyday, the vigorously anti-Communist periodical saw monthly circulation in the low hundreds of thousands, but that began to decline at the end of the Cold War. In the 1980s, while in the Army, I occasionally read the magazine’s reports out of Afghanistan concerning the Soviet army—potentially, my real-world enemy.

In late 1995, I had left a job with an up-and-coming weekly newspaper in Texas to edit the controversial military/firearms publication located, oddly enough, in a trendy college town on the Rocky Mountains’ Front Range. It had its moments. A magazine is similar to a newspaper; both are hungry mouths always needing to be fed. So, when I read a lengthy article based on an interview with Thompson at his storied cabin in Woody Creek, near Aspen, in a weekend edition of the Denver Post, one remark leapt out. The maverick writer of books and stories in notable magazines such as Rolling Stone disparaged then-President Bill Clinton, calling him more of a “fascist” than Richard Nixon. To someone who had not read much of Thompson’s work, the odd remark might not have been especially noteworthy—but it was to me.

While not exactly a devotee, I nonetheless had read most of Thompson’s books and enjoyed his trademark research and writing style, known as gonzo: a form of “participatory journalism” with no pretense of objectivity and detachment, usually in the first-person and occasionally delving into the flamboyant writer’s (ahem) chemically fueled misbehavior.

Thompson despised President Nixon and never had missed an opportunity to badmouth him. The comparison with Clinton was surprising, but Thompson was eccentric—or that was his very successful shtick anyway—and trying to categorize him was pointless. The hard-drinking, Kentucky-born writer had a widely publicized love of firearms, particularly large-caliber revolvers, and a lesser-known membership in the National Rifle Association, as well as a familiarity with Soldier of Fortune magazine. I saved the Denver Post article and formed a plan. I would mention Thompson’s disparagement of Clinton in the next issue of the magazine and mail Thompson a letter and copy of that issue, asking if he would consider expanding on this line of thought in an essay for us. The other editors agreed an out-of-the-blue piece by Hunter S. Thompson could spike newsstand sales and maybe attract new readers. And, for some reason, Reisinger had Thompson’s mailing address on his trusty Rolodex. A manila envelope soon headed west toward snowy Woody Creek.

Several days after Thompson’s phone message, his letter arrived at Soldier of Fortune’s offices on Arapahoe Avenue in east Boulder. Nestled in a business park, the magazine’s well-worn headquarters smelled of gun oil, old newspapers and magazines, and big-game taxidermy. The letter comprised a few typewritten lines. Thompson thanked me for the mention in Soldier of Fortune but added it probably would put him on some “bad lists.” Even so, he continued, he would discuss my offer further, but only if the magazine delivered to him two Ruger ‘Super Redhawk’ revolvers chambered for .454-caliber Casull ammo and with telescopic sights.

I reread the letter, then tossed it on my desk. I knew such firearms fell into the category of hand cannons, with large price tags. Despite its reputation, the magazine did not keep hardware like that lying around. This was a very lean operation.

Well, that kills it, I thought, disgusted…. The other editors concurred. And publisher and expenses aside, I frankly was not keen on the idea of delivering guns to an outlaw writer—however famous—who had experienced more than a few real run-ins with the law.

This futile dalliance was a departure from my normal duties at the magazine. In my two years at Soldier of Fortune, I mostly edited feature-length articles contributed by correspondents, seasoned freelancers, and first-time writers.

READ MORE from another longtime correspondent at Soldier of Fortune.

As deadline-driven editing went, it was challenging work. I usually had three feature-length edits per magazine, which eventually totaled 24 issues. Fact-checking authors’ descriptions of US and foreign weapons, equipment, and vehicles required I spend hours in the magazine’s eclectic library, sometimes carrying stacks of the encyclopedic Jane’s Defense books published in London back to my desk.

I was allowed out of my editorial “cage” once, to travel to Camp Frank D. Merrill in northern Georgia where I spent two days in the woods with a US Army Ranger-school class slogging through Mountain Phase. The result was my “Ranger, Lead the Way!” cover story in the November 1997 Soldier of Fortune. That issue flew off newsstands, snapped up by soldiers who read it in preparation for the grueling infantry-leadership course I had completed 13 years earlier.

The magazine’s readers were picky—and knowledgeable. For example, if a photo showed a Russian-made T-64 tank but it was misidentified as a T-62, we would get a few irate or snarky letters. What writing I did do typically was uncredited sidebar articles and technically precise photo captions rounding out contributors’ features.

A caveat that remains to this day.

Because I had not just one but two journalism degrees, I additionally was designated as the office’s primary point of contact for outside queries. The New York Times’ Denver bureau, a British newspaper correspondent, the Rocky Mountain News, local or national TV—I never knew who would be at the other end of a phone call. Sometimes it was goofy….

And sometimes the phone call was serious.

One afternoon Helena, our Swedish receptionist, announced via intercom she was transferring a call I really needed to take. When my phone rang, I stopped pounding on my computer keyboard, irritated at the interruption, and picked up the receiver.

It was the FBI.

The special agent politely introduced himself and said he worked out of the Boston office.

“OK,” I replied. “What can we do for the Bureau today, Agent?”

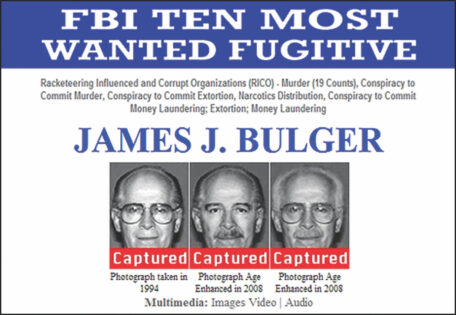

He asked me if I ever had heard of James “Whitey” Bulger.

“Isn’t he a wanted felon?” I replied, straining my brain. “A killer?”

The FBI agent replied affirmatively. He explained that this most-wanted felon was an Irish–American mob leader in South Boston who had committed many serious crimes, including the cold-blooded murders of more than a dozen people. Bulger had slipped away a few years earlier and gone into hiding, probably with his girlfriend and suitcases full of cash and guns. Investigators were coming up empty-handed, with no leads. That was why, the agent said, the FBI now wanted to purchase advertisements in Soldier of Fortune magazine seeking information leading to Bulger’s arrest.

“Really? Well, our readership does include military veterans, law-enforcement officers, mercs [mercenaries], and bounty hunters,” I said.

“Yes, we know,” the special agent said cheerfully. I jotted down a few notes, then put him on hold and dialed our advertising department. The result would be a quarter-page ad purchased for two upcoming issues of the magazine. Meanwhile, I phoned a mainstream journalist I knew, Editor Peter Copeland at the Scripps Howard News Service in Washington, D.C., with a heads-up. A reporter then was assigned to research and write a story. On Sept. 25, 1997, Scripps Howard broke the minor national news of this unusual FBI–Soldier of Fortune collaboration:

The FBI has turned to an unlikely source to help find notorious Boston fugitive James “Whitey” Bulger. Buying ads in Soldier of Fortune, a magazine often critical of federal law enforcement agencies. Bulger, 68, subject of a worldwide FBI manhunt and $250,000 reward offer … [was] the head of a crime gang that ran South Boston’s loan sharking, gambling and drug trade, law enforcement officials said. Among the dozens of crimes he has been linked to was a 1984 effort to smuggle seven tons of guns to the Irish Republican Army. That’s one reason the FBI may have bought an ad in a magazine read by an international audience of mercenaries, adventurers, gun enthusiasts and military people. “It gets down to who reads our magazine,” said Soldier of Fortune assistant editor Marty Kufus. “Bounty hunters read us, skip tracers, bail bondsmen. We are also read by the IRA.” And the Boston FBI believes Bulger himself may be a fan of the magazine, a source said.

The FBI’s advertising campaign, which reportedly used the USA Today newspaper as well, brought no arrest. More than a decade passed. Bulger and his longtime girlfriend, a younger woman from Boston named Catherine Greig, remained on the lam—until June 2011. A tip led to their arrests at an apartment building in Santa Monica, California, where the couple had been living modestly, yet comfortably, under false names since 1996, according to news reports.

Eventually, the dots connected in my head. I read an exhaustively researched book: America’s Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt that Brought Him to Justice by Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy about the notorious gangster’s life and criminal career. Written by two award-winning Boston Globe crime reporters, the book also detailed Whitey Bulger and Catherine Greig’s quiet life as retirees settling into Santa Monica.

“Using her Carol Gasko alias,” the book said, “Greig subscribed to the Los Angeles Times and got Whitey a subscription to Soldier of Fortune magazine, which is geared to those interested in weapons and military tactics.”

Task-force investigators’ likely hunch in 1997 that Bulger read Soldier of Fortune was correct. It is possible, even likely, he saw the FBI’s ads. Maybe that flattered the narcissistic Bulger. Or, possibly, it sent a chill through the aging body of the stone-cold killer many people wanted imprisoned or dead. After all, Soldier of Fortune also practiced “participatory journalism”—just not gonzo.

Author Martin Kufus worked as the assistant editor of Soldier of Fortune magazine from 1995 to 1997 in Boulder, Colo., and served in the US Army in the 1980s as a Russian linguist and Ranger-qualified paratrooper. His first book, Plow the Dirt but Watch the Sky: True Tales of Manure, Media, Militaries, and More, is a nonfiction narrative ranging from chapter “A is for America” to “Z is for Zodiac” (flood-rescue boat). It is available at Amazon.com for purchase as a soft-bound book or Kindle download. Chapter “G is for Gonzo” is excerpted here with the author’s permission.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers