by Martin Kufus

Excerpted from Plow the Dirt but Watch the Sky: True Tales of Manure, Media, Militaries, and More, by Martin Kufus.

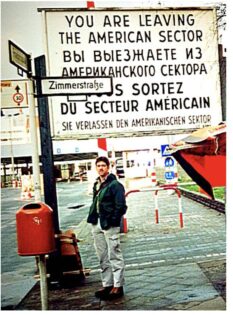

And the sign said YOU ARE LEAVING THE AMERICAN SECTOR.

Our Mercedes bus idled at Checkpoint Charlie, the tightly controlled Allied crossing through the Berlin Wall into the Soviet-occupied side of the divided city. Soldiers of American Berlin Brigade, British Berlin Infantry Brigade, and French Forces in Berlin manned the famous checkpoint that wasn’t much more than signs, moveable gates, and a prefabricated building about the size of a mobile home. It was February 1988.

All paperwork in order, our bus driver slowly moved us out of West Berlin to the next stop. About 50 yards ahead was a much larger checkpoint manned by East German Grenztruppen (Border Guards) and Soviet overseers. That was communist East Berlin, cold and gray.

As if on spoken command, we tourists—Allied military and civilian alike—held our photo-ID cards or passports against the window with one hand while rigidly facing the front of the vehicle. We had been admonished to make no eye contact (a possible provocation) with the Border Guards who checked everybody entering East Berlin from the West and coming the other way.

Sitting motionless in my bus seat, I peripherally noticed a Border Guard stop outside my window, look closely at my laminated US Army ID card, then pivot and step to the next window. The steel-helmeted soldiers wore gray–green uniforms, and the automatic rifles slung over their shoulders were the AKM upgrade of the AK-47. The curved Kalashnikov magazines, no doubt, held live ammunition.

Kufus as tourist in West Berlin, with Checkpoint Charlie in the background, 1988.

The menace here was palpable. Since 1961, when the Communist regime began building the Wall, many East Berliners had been shot and killed by their own countrymen, some from guard towers along the hated barrier, while trying to flee to the West. Nowadays, the Wall on the west side was covered with wild, colorful graffiti—touristy and stupid, obscene, some anti-Communist (Nyet Nyet Soviet!)—but the 12-foot-tall barrier’s east side had none.

After a few minutes, during which our tour bus’s paperwork also was scrutinized, the senior Border Guard waved us through. One of my fellow passengers, maybe a GI’s wife, audibly sighed with relief. There was nervous laughter. This is so cool, I thought, enjoying the tense Cold War vibe.

At 31, I was preparing to leave the Army in three months. A trip to West and East Berlin was on my must-do list before returning to the States for discharge.

Indeed, the Cold War seemed to have no foreseeable end. In my mind, after almost 2 1⁄2 years’ duty in West Germany, the zeitgeist reverberated with Ronald Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” speech, West Berlin rock band Nena’s anti-war song “99 Luftballons,” and Austrian singer Falco’s “Der Kommissar” and “Rock Me Amadeus.”

For this excursion into a communist country, I had flown via commercial airline from Munich to West Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport. I slept on the sofa in an apartment occupied by an Army buddy, a German linguist in signal intelligence (SIGINT), and his wife. This allowed me to make two half-day treks into East Berlin as well as take in the vibrant West Berlin’s sights and a bit of its nightlife, which locals pursued as if they had no tomorrow. This somewhat fatalistic outlook was not hard to understand. Their surrounded city was, after all, at the crosshairs of the Cold War. During the Cold War the US military encouraged its troops, the better-behaved among them, of course, to visit East Berlin to exercise the Allied right of access; to simply show the colors, as it were, even if Soviet and East German authorities did not especially like having them there.

Those GIs who wanted to travel beyond the Wall into the East filled out the paperwork and applied for permission. We were screened for trustworthiness and good behavior; those who made it through that filter were given counterintelligence briefings on what to expect and be wary of in communist East Berlin.

Then, we took leave time from our duty stations and paid our own way for travel by air, rail, or ground vehicle via “the corridor” through East Germany into West Berlin. Soviet troops occupying East Germany, however, weren’t so privileged. The only Soviets who regularly passed through Checkpoint Charlie into the American, British, and French sectors, I was told, were observers from the GRU (the military’s Main Intelligence Directorate) driving little green cars of the Soviet Military Liaison Mission—SMLM or “Smell ’em” to Americans and Brits—and usually tailed by Allied counterintelligence agents.

East German guard tower overlooks the Wall, seen from the west.

Having cleared the border crossing, our tourist bus pulled to a halt in front of a department store at the wide square called Alexanderplatz. East Berlin, I had heard, was considered by the Soviets to be “the economic showcase” of the Warsaw Pact nations. Plain and utilitarian, the large building had a few floors of public commerce. Above them, though, were several floors hidden behind big, mirrored windows. These probably were surveillance perches for binocular- and camera-equipped KGB or GRU personnel and/or East Germany’s Stasi, the feared and hated State Security Service whose “secret police” spied on and terrorized their own people.

Our tour guide–escort, a British woman, told us to return by a certain hour if we chose to separate from the group. It would be cause for alarm if someone did not return on time, she cautioned.

The sky was gray but the weather was mild for February in Germany. I carried a point-and-shoot, autowind 35-mm camera on a shoulder strap and wore my Class-A uniform: black dress shoes, pickle-green suit pants and jacket, long-sleeved shirt, black clip-on necktie, and matching green garrison cap. The only thing missing was my name tag, which I had removed as instructed.

There was little doubt American soldiers in East Berlin were watched, photographed, and possibly followed at a discreet distance, especially if someone piqued somebody else’s interest. I halfway suspected I might earn such an honor.

Starting at the top, my garrison cap bore a metal unit pin for the “Home of the Professionals:” Field Station Augsburg, the Army–National Security Agency SIGINT facility in Bavaria. Field Station Augsburg’s sister SIGINT site in Germany was Field Station Berlin—no doubt, on a Soviet first-strike or capture list.

A round brass pin on my left lapel confirmed my occupation in military intelligence. I was a sergeant (three yellow chevrons on each sleeve) with at least six years’ service (two hash marks on a sleeve)—no big deal. A single row of ribbons above my jacket’s left breast pocket represented a small number of not particularly significant medals. Hanging from that pocket was a badge for ‘Expert’ marksmanship with both rifle (M16) and pistol (.45 caliber)—nothing remarkable. However, my unit patch was of the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command. Above it on my left arm was an orange-and-black Ranger-qualification tab. On the left side of my chest were pinned silver “jump wings” denoting parachute qualification; on the right side of my chest were larger, silver Egyptian jump wings.

Although I was a tiny cog in the big machine that was the Army in 1988, something peculiar did happen to me in East Berlin. Maybe it began in the big department store at Alexanderplatz, where secret police could blend in with shoppers.

Minding my manners, as soon as I entered the department store I removed my garrison cap and stuck it in a jacket pocket, then strolled around the first floor looking at the shops. Seeing nothing that interested me—too bad, as the East German 100-mark bills adorned with Karl Marx’s ugly mug were burning a hole in my pocket—I silently got in line for the escalator. On the slow ride to the next floor I watched, out of the corner of my eye, the line of East German shoppers coming down the other escalator. Many of the men and women side-eyed me, not with hostility but with curiosity or perhaps even hope at the confident presence of an American soldier. I felt a swell of quiet pride wearing that uniform in that place at that time. The escalator ride ended. I entered a modestly stocked sporting-goods shop. Politely speaking German—most GIs couldn’t—I purchased a nice compass in a flimsy plastic carrying case.

The 1,200-foot Television Tower rises over Alexanderplatz, the hub of East Berlin.

Leaving the department store, I followed the city sidewalk for a few blocks to what obviously was a gift shop for foreign tourists. I kept to myself as I looked at the trinkets, clothing items, and printed material on the shelves, all for purchase at the equivalent of pennies on the US dollar. Unexpectedly, a “friendly” voice came from behind.

“Are you enjoying your visit in East Berlin, mister?” the voice said, in German. I turned and looked. Standing a few feet away was a 30-something man wearing a wool driving cap, leather or maybe a fake-leather jacket, and dark slacks, smoking a pipe. I hadn’t noticed him when I came into the store; maybe he had entered after me. Earlier, our British tour guide–escort warned us to ignore any East Germans who tried to start a conversation. But I didn’t follow instructions.

Yes. It’s going well, thanks. I continued shopping.

Pipe-smoker persisted. Perhaps you are interested in something else? Two people joined him: a 30-something man sporting a shaggy mustache, slacks, and a thick sweater, and a pretty, young blonde woman in knee-high boots, a skirt, blouse, and matching jacket, with a handbag hanging from her shoulder. She smiled at me but her eyes were cold.

“No thank you,” I replied, shaking my head – and turned away. That didn’t end the encounter. In a practiced motion, the trio advanced, put arms around my back and shoulders, and tried to pull me along with them as if I was their newfound drinking buddy.

“Es ist OK,” pipe-smoker said, laughing. “It’s OK. Come with us. “

Stopping dead in my tracks I dropped my shoulders, crouched, and anchored my 195 pounds to the floor. Feeling the sudden resistance, the trio kept on walking, not looking back, to the front door and out.

Did Stasi make a pass at me? I wondered.

READ MORE from Martin Kufus: Guarding the ‘Floating Bomb’ on Halloween, While Somali Pirates Prowled the Seas

It was time to move on. I stopped at the front counter to buy copies of the communist “New Germany” and Russian Pravda “Truth”) newspapers, then headed for the door. Outside, I stopped and looked for the troublemaking trio. If necessary, I would’ve made a beeline back to the limited safety of our parked tour bus. I didn’t see anyone suspicious, however, so I continued on. Farther down the street I found a small coffee shop. Inside, I took a table. A waiter approached and greeted me.

“I would like a cup of coffee with sugar and a bottle of mineral water, please. Then, opening the newspapers, I spent the next 15–20 minutes catching up on the latest anti-American/anti-NATO propaganda.

Prior to entry into East Berlin, we also were cautioned to be careful of what we photographed. It could be considered provocative – spying – if a Westerner pointed a camera at anyone in East German or Soviet uniform or at any operational military or security vehicles or buildings. Historical sites were a different matter.

With other tourists, I slowly walked through the Museum of the History of the Unconditional Surrender of Fascist Germany, which was a regular stop for Westerners. Outside the building an immaculate, WWII-era Soviet T-34 tank stood on a concrete pedestal. A patriotic slogan in large, white letters on the tank’s turret proclaimed РОДИНА–МАТЬ! (Homeland–Mother!). In the center of Berlin, several Western tour groups converged at the Memorial to the Victims of Fascism and Militarism: the 19th-century Prussian Neue Wache (New Guardhouse), a large masonry structure with portico and Greek-style columns, now housing an “eternal flame” and the remains of an unknown Soviet soldier and a Nazi concentration-camp victim. Soon, an honor guard of East German soldiers—helmets, greatcoats, polished boots, SKS rifles, and bayonets all spotless—goose-stepped through a ceremonial changing of the guard.

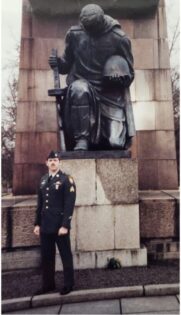

On my own I visited Treptow, the Soviet war memorial. According to literature, it held a mass grave of 5,000 of the 80,000 Red Army troops who died in 1945 in the final push to seize Hitler’s Berlin. I’d never seen anything like it. Almost the size of a soccer stadium, the flawlessly manicured grounds were dotted with large statuary and monoliths etched with patriotic slogans. I walked slowly, taking it in. It was a surprisingly moving experience. After a half-hour, I strolled toward the exit. A civilian couple approached. They were speaking Russian to each other.

“Извините меня,” I said to them, smiling. “Excuse me. Can you please photograph me with my camera?

“Да, конечно,” the man replied. Yes, certainly.

I handed him my camera and indicated which button to push. I stepped back and posed in front of a magnificent, larger-than-life statue of a Red Army soldier kneeling on one knee, helmet cradled in left hand, PPSh-41 submachine gun held in the right, head bowed in sorrow. The man snapped my picture. I thanked him and we parted company.

Kufus outside Treptow, the Soviet army’s WWII mass grave and memorial in East Berlin.

A must-stop location in East Berlin, other field-station linguists had told me, was a bookstore with a Russian section upstairs. I walked into the bookstore and followed the signs to a stairwell. At the top of the stairs, I entered a room where everything was written in Cyrillic. A well-dressed, middle-aged woman was shelving books. She could’ve been the wife of a Soviet Army or KGB officer stationed in East Berlin.

“Hello,” I said, smiling and nodding.

“Good day,” she replied pleasantly as I walked by.

I glanced around at the walls and ceilings, wondering where the secret microphones and cameras were hidden—a distinct possibility. I saw nothing. But that didn’t necessarily mean there wasn’t anything there; I had not been trained in counter-surveillance.

After browsing for a few minutes, I found two authoritative reference books to buy. I placed the hardcover books in a small hand basket and took it to the counter. A second woman, probably another Soviet officer’s wife, pleasantly greeted me there. I placed the basket on the table.

Good day, I said, smiling. I want to buy these dictionaries, please.

Yes. Just a moment, please. The clerk picked up the two books, returned them to their places on the shelf—they were for display, not purchase—then walked into the back room, returning shortly with the dictionaries for purchase. She figured my bill on a cash register, then confirmed the total with a pencil and notepad. She told me the price, I handed her East German cash, and she counted out my change. That came to a grand total of about 5 bucks American, I figured, silently, as she placed the books in a paper sack.

As I left the bookstore, I wondered which of those nice ladies upstairs would phone their KGB or GRU contact with an incident report about a Russian-speaking American paratrooper buying two of their best dictionaries.

At the field station back in Augsburg, people like me spent countless hours in SIGINT “intercept”—real-time radio eavesdropping and recording and translation—of Soviet soldiers in East Germany transmitting from garrisons’ headquarters, truck convoys, infantry combat vehicles, tanks, self-propelled howitzers, and multiple-rocket launchers, and once in a while a ballistic missile’s transporter–erector–launcher in its hide site. We listened in as armored, motorized-rifle, and artillery units conducted live-fire exercises lasting hours and sometimes days in preparation for a war in which they would try to kill people like us. Nothing personal—it was a fact of military life in the Cold War.

On my second and last day in East Berlin, I quietly joined four Soviet soldiers, wearing their olive-green service-dress uniforms, on a street corner. I stood on the right end of their line abreast, a foot or two from the nearest guy, as we waited for the light to change and the smoggy traffic to stop for the crosswalk. Out of the corner of my left eye, I noticed the soldier at the other end of the line lean forward slowly and tilt his head to sneak a look at me. His mannerism was so … Russian. Being a bit of a wise guy then (hard to believe, yes), I leaned forward and looked to the left. Our eyes met. The young Soviet soldier immediately looked away and snapped back to an upright position. Traffic stopped and we went our separate ways.

Surveillance video of that wordless encounter would’ve revealed an unmistakable smirk on the American’s face as he walked away.

Martin Kufus was a staff editor at Soldier of Fortune magazine, 1995–97. You can find his book here.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers