by Elizabeth M. Collins

“Enemy in the wire! Enemy in the wire!” The news, the stuff of nightmares, spread through Red and Blue platoons in seconds. “Enemy in the wire.” Many soldiers didn’t believe it at first. It was a phrase they never expected to hear, one they dreaded.

It couldn’t be true, they reasoned. The battle for Combat Outpost Keating, for their very existence, had started less than an hour earlier, as 3 October, 2009, dawned, when some 300 insurgents had surrounded the small outpost manned by about 50 Americans, an Afghan National Army unit and its two Latvian trainers. The fighting was intense, but the enemy couldn’t possibly have breached the base that quickly, could they?

READ MORE from Soldier of Fortune about the Battle of COP Keating

Crouched behind the COP’s aid station a short time later with a couple of other Soldiers, Red Platoon’s lead scout and acting platoon sergeant, now-former Staff Sgt. Clinton L. Romesha, didn’t quite believe it as he watched three enemy fighters casually stroll through Keating’s entry control point. They sat down behind one of the HMMWVs as though they had already won the battle.

One of the fighters even leaned his shoulder-fired anti-tank rocket launcher [RPG] against the truck and reached up to tighten his headband.

“I kind of thought to myself, ‘Is this real?'” Romesha remembered. “We had three Taliban fighters just walk right through our front gate and put foot in our home.”

Romesha had already been fighting hard, exposing himself to enemy fire countless times; he had the shrapnel wounds to show for it, but enough was enough. He squeezed the trigger on his trophy Soviet sniper rifle and “put an end to that.” It was time to take Keating back.

Romesha, “Ro” to his Soldiers, seemed fearless as he ran from one position to another, securing this building, closing that entrance, inspiring his troops with his resolve and steely sense of calm.

“I think that’s what gave more motivation to Soldiers, just to see that this guy had no fear,” said now-Staff Sgt. Armando Avalos Jr., the unit’s forward observer. He just looked like an old Vietnam veteran with this long mustache, and just to see him out there, directing … not once was he ever questioned. He was precise, he was confident and he knew exactly what to do.”

To recognize that courage, the valor that Romesha showed throughout the 12 hours it took to retake and secure Keating, President Barack Obama awarded the him the Medal of Honor in a White House ceremony on 11 February, making Romesha just the fourth living Medal of Honor recipient from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s something he never set out to achieve or really ever wanted. It’s an honor—the highest of honors—that he will wear with pride for the eight Soldiers who died that day. But the cost, he explained, was just too high. He’d gladly trade it in to bring back even one of those men.

A MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENT IS BORN

The son of a Vietnam veteran and grandson of a World War II veteran who took his brother’s place in the draft, Romesha was born to serve. He grew up on his grandfather’s stories of landing on Normandy only two days after D-Day and always knew that when he turned 18, he would follow in his grandfather’s footsteps. He left the Mormon seminary he had attended while still in high school to become a heavy armor Soldier.

Romesha headed to Germany in 2000 with his new wife, his high school sweetheart Tammy, and was soon sent to Kosovo; later he was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division in Korea. There, he learned one of his old noncommissioned officers had been killed in Iraq.

Around the same time, parts of the 2nd Infantry Division received deployment orders. He could do no less than the mentor who had sacrificed everything, Romesha reasoned. So he went to his colonel and asked to go to Iraq. He didn’t bother to discuss it with his wife. It was just something he had to do.

A new assignment with the 4th Infantry Division brought a second deployment to Iraq and a new specialty: reconnaissance scout. He had liked armor, but being a scout suited him.

“I liked being light,” he recalled. “I liked being fast. I liked observing and kind of being the silent overwatch that no one knows is there.”

He enjoyed teaching his Soldiers all of his tricks, too, and was always happy to give pointers, even during his downtime, said now-Sgt. Thomas Rasmussen, who served under Romesha in both Iraq and Afghanistan.

Romesha, Rasmussen added, was definitely the best noncommissioned officer (NCO) he’s ever had. He was tough and he pushed his Soldiers hard, but he was fair and there was never any doubt that he cared about them. His sense of humor was goofy and weird and perhaps even dark, Rasmussen and Avalos agreed.

“He’s always the one making stupid jokes,” Rasmussen continued, “or pissing off a lieutenant just to make everyone else laugh, or getting on somebody’s nerves just to lighten the mood or cracking jokes at the most inopportune times.”

THE LOW GROUND

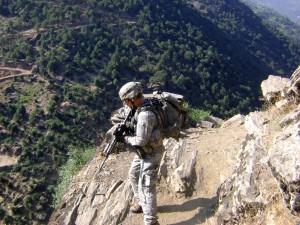

Romesha, Rasmussen, Avalos and the other men of Bravo Troop, 3rd Squadron, 61st Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, arrived in remote Nuristan Province, Afghanistan, in late May 2009, about four months before the attack on Keating. Nestled in the Hindu Kush mountains along the border with Pakistan and cut off from much of the modern world, Nuristan is poor, semiautonomous and home to fiercely independent people suspicious of outsiders.

Expect to get in a lot of firefights, Sgt. Josh Kirk told his buddies before they deployed. He had already spent a year in the area with the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, and warned his new unit that it was extremely dangerous. The local insurgents were nothing like those they’d faced in Fallujah and Ramadi, Iraq, either. Here, the mujahideen were well trained and well supplied; many of them had honed their military skills fighting the Soviets. Two of the four previous American commanders of Keating had been killed, possibly even targeted, by insurgents.

Even worse, Kirk explained, COP Keating sat in the worst possible location for an outpost. It sat on the low ground, surrounded by 10,000- and 12,000-foot mountains blanketed with trees and boulders and nearly invisible trails. Even with that warning, the men of B Troop were stunned when they arrived. It was like being in a fishbowl or fighting from the bottom of a paper cup, said then-Sgt. Brad Larson (now a first lieutenant).

The mountains and the local river were stunning, “beautiful in a way that if there wasn’t a war going on, you could have made a killing off the rapids,” Romesha said. “But tactically speaking, it was pretty dismal. That first morning I remember thinking to myself, ‘I’m going to have the strongest neck muscles from looking up for an entire year.'” It was hard to explain to his Soldiers why they were there, why the Army had stuck them some place that went against every ounce of training they had ever received, as Avalos put it. In the end, it didn’t matter.

“They all dug deep,” Romesha continued. “They knew it was their duty. It was our job to sit there, and we were going to defend whatever they gave us.”

That was easier said than done. The enemy attacked almost every day, often multiple times a day, for four months. Rasmussen preferred it that way, however. It was easier on the psyche, he found, to openly shoot back and forth at an enemy than it was to “go driving around in a truck all day waiting to get blown up” by improvised explosive devises the way they had in Iraq. There were always rumors too, intelligence reports, radio whispers, locals who said insurgents were planning to overrun the outpost. But after the 10th or 20th such report, it was like crying wolf, Romesha explained.

The Army was planning to close Keating. It was, leaders realized, too hard to defend and the area too dangerous for provincial reconstruction teams. U.S. forces could make better use of Bravo Troop elsewhere. After a few delays, the date was set: Bravo Troop would withdraw in mid-October.

Even on a good day, life at the football field-size COP Keating was rough. Most of the buildings were tin-roofed structures built of stacked rocks and plywood. The Soldiers were lucky to get a hot meal every other day and a hot shower once a week. To pass the time and deal with the unrelenting stress of constant attacks, the men held competitions to see who smelled the worst after a week without a shower, or who could down the most meals, ready-to-eat (MREs).

They talked about how they would overrun a base like Keating. They played cards. They lifted weights. They talked about their families, about what they wanted to do when they got back to Fort Carson, Colo., and they played pranks. During one particularly memorable prank, Larson and Rasmussen (better known as “Raz”) captured one of the ubiquitous wild goats that roamed the area and locked it in their lieutenant’s room while he was sleeping. It was the funniest moment of the deployment, Avalos remembered.

Larson and Romesha were close, so close that in a firefight they could look at each other from several hundred feet away and know what the other was thinking. It was those friendships that got them through the summer of 2009.

“We could sit there and talk for hours and not actually say anything,” Romesha explained. “Relying on that friendship and your battle buddies was what you did. You didn’t sit there and reflect on when we were getting hit next. You just knew your training would take over, your NCOs would be there to support you and you’d stick together and you’d come out of it next time.”

DAWN ATTACK

“Next time” came at dawn on 3 October, 2009, when most of the Soldiers were jolted awake by a barrage of enemy fire minutes before 6 a.m.

“The thing that woke me up was the sound of the B-10 recoilless rifle,” Avalos remembered. “It makes a distinct sound, especially being at the bowl of the mountain. Just the echo of it sounded like a freight train coming. No matter where you were, as soon as that bad boy went off, you woke up.”

Romesha knew within 20 seconds of that first shot that this attack was different, something more than the daily contact they were used to. This was the attack they had been warned about.

“It was just one of those things you could hear in the air,” he said. “The volume that it came in on and the precision it was hitting us at, you just knew. It was just one of those instincts.”

The bombardment, from B-10s, RPG rockets, anti-aircraft machine guns, Russian-made “Dishkas” [DShK, a .50 cal. heavy machine gun], mortars, snipers and small arms fire, came from every direction. The insurgents knew exactly what spots to target and pinned down the American mortars almost instantly, all the while carrying out a simultaneous attack to distract the mortars at nearby Observation Post Fritsche.

“Every position was overwhelmed,” Romesha explained. “Every position was pretty much from the get (go) pretty ineffective.”

At first Romesha thought, “‘Game on! All right, we’ve got a challenge. Come on boys, let’s do this. Let’s get back at them.’ As I look back, I was just letting instinct take over. I don’t recall having too much thought other than ‘I’ve got battle buddies out there.’ It was like a man test, the ultimate man test: Step up to the plate or go home, and we were going to step up to the plate, just to prove the point that we’re better than you. We’re not going to be held down.”

ROMESHSA LEADS THE CHARGE

“Dude, you’re bleeding,” Spc. (now Sgt.) Thomas Rasmussen told his acting platoon sergeant. Did Romesha want Rasmussen to patch him up?

Half surprised, Romesha glanced at his arm. An RPG rocket, had damaged the generator he was using for cover a short time before, peppering the right side of his body with shrapnel. He barely noticed as he unloaded the last of his ammo at some of the roughly 300 insurgents who were trying to overrun COP Keating.

It was partly his fault. He had been so focused on picking off the enemy, positioned above Keating’s location at the bottom of four 10,000-plus-foot mountains, that he broke one of the cardinal rules he drilled into his Soldiers: “‘Don’t put the blinders on.’ I had gotten pretty fixated on engaging the enemy (to the north). The enemy was able to skirt in to my right flank.”

Go ahead, he told Rasmussen, “Just throw a bandage on it real quick.”

There was no time for anything else. Barely an hour had passed since the attack had begun. Three Soldiers from Bravo Troop were already dead. Others were wounded. Several were unaccounted for. Keating was on fire, and they had lost power when the RPG rocket hit that generator. Enemy insurgents were inside the wire. The Afghan National Army soldiers who had been stationed on the east side of Keating were abandoning their posts.

“We weren’t even close to being done with the fight at that point,” Romesha said.

“I’M SORRY”

Seven Soldiers were trapped outside Bravo Troop’s “Alamo” perimeter, the small section of Keating that U.S. forces still controlled that housed some of the barracks, the tactical operations center (TOC), and the aid station. One of the men was one of Romesha’s closest friends, Sgt. (now 1st Lt.) Brad Larson, who had just taken over at the LRAS-2 [Long Range Advanced Scout Surveillance System) HMMWV when the attack started. He was pinned down almost immediately, as were Sgt. Justin Gallegos, Sgt. Vernon Martin, Spc. Stephan Mace and Spc. Ty Carter, who arrived at the LRAS-2 to either assist or to bring more ammo, something the men needed desperately—Larson alone had gone through approximately 1,200 rounds in 10 minutes.

Then, enemy shots hit both an M-240 machine gun and a .50-caliber machine gun, rendering them useless. The blanket of bullets was so thick, Larson recalled, that they couldn’t even crack the HMMWV’s windows to shoot out with their M-4s.

“I had no doubt I was going to die that day,” he said later. One Soldier was dead and two others were pinned down at a second location.

Romesha thought he could help them, but the enemy fire was just too intense. He apologized to the men. He felt terrible for leaving them there, but he would be back. Air support (Apaches and multiple types of fixed-wing aircraft) had finally arrived. He had to trust that they would be OK.

CLOSING THE GATE

In the meantime, Romesha had insurgents to kick out of Keating, an ammo supply point (ASP) to secure and a gate to close. He grabbed a Dragunov sniper rifle from a wounded Afghan National Army soldier—his own M-4 was running low on ammunition—and ran through open fire, as he would many times that day, to check on their one operational gun truck, which Spc. Zach Koppes was manning, alone, while being stalked by an enemy sniper. Romesha played “peek-a-boo in and around the HMMWV, trying to pinpoint who was shooting at (Koppes). We kept exchanging fire and it finally subsided.”

After stopping along the way to talk to his platoon leader, 1st Lt. Andrew Bundermann (who was also the acting ground commander), and to kill three insurgents he had found inside the wire, Romesha “played the bullet dodge back to the barracks” and asked for five volunteers to help secure the ASP and retake the entry control point. “They stepped up without hesitation,” he said, calling the Soldiers’ actions “amazing.”

It was an easy decision, Rasmussen said: “The enemy is in your house, so you’re either going to sit there, and they’re eventually going to kill you, or you’re going to fight back.” Romesha’s fighting spirit, his determination and his courage helped too, Rasmussen added. “It made me want to go (on) until I got shot or until we got (Keating) back.”

Soldiers from Blue Platoon (Romesha was the acting Red Platoon sergeant) were supposed to provide fire support as the six men bounded to the ASP, but fighting on the other side of Keating held them up. By then, “we had pretty much run out of ammunition at all the fighting positions for the MK-19 grenade launchers, the .240 machine guns,” Romesha explained. “We also knew that the enemy being in the wire, it was going to be a close firefight and one of the best things to have on your side is the good old fragmentation grenade. It was to the point where we needed more to continue on.”

They made it to the ASP without cover fire from the ground. Just as they started divvying out ammo, enemy fighters charged toward the barriers that ringed the ammo point. The fighting was heavy and one Soldier was shot in the shoulder, but the men’s fresh supply of fragmentation grenades helped them fight off the attack.

“I can’t wait in this position any longer,” Romesha radioed Bundermann, telling him it wasn’t safe for his Soldiers. He also worried that insurgents would “start carting off our dead.” They had to close that gate.

Bundermann sent out another Soldier and promised additional help, but once again, Romesha decided to move forward without additional support. Instinct had taken over. They had to fight inch by inch to secure the shura building (next to the entry control point) and block off the gate, Rasmussen remembered. Once they were inside, the enemy unleashed a fresh volley of RPG rockets and B-10 rounds and he started to wonder if they were going to make it. “(Romesha) just looked at me and was like, ‘No, bro. Keep your head up. We’re going to make it out of this,'” he said.

“It was like he had already been through that once and he knew exactly what to do to win,” Rasmussen continued. “He was like, ‘We need to do this. We need to do that,’ left and right, and just barking shit out like there’s a study guide for this shit and he’d already mastered it. I was just in awe the whole time. I never questioned anything. When you have someone above you with that much determination and that much confidence and that much skill, you’ll follow him to the gates of Hell with no questions asked and go fight the devil head on.”

With their new position, they could keep additional insurgents out of Keating. Romesha was able to identify more enemy targets in the neighboring village for the Apaches and F-15 pilots. The entire valley shook from the force of 2,000-pound bombs and enemy fire finally began to slow. The tide had started to turn.

UNACCOUNTED FOR

It was time to try to account for their missing Soldiers. At some point that morning, Bravo Troop had lost radio contact with the five men at LRAS-2. Another Soldier, Sgt. Josh Hardt, had been determined to lead a rescue attempt that quickly became a suicide mission. One Soldier was killed in seconds, another was wounded and Hardt had gone missing after radioing in that an RPG was pointed at him.

The men knew they couldn’t stay at LRAS-2 much longer, but Gallegos and Martin were killed almost as soon as they left the HMMWV and headed for cover, and an RPG rocket exploded in front of Mace, leaving him with serious leg and abdominal injuries. Hit in the helmet by a sniper round, Larson continued to provide cover fire, shooting two insurgents who were headed straight for them.

“Get back in the truck,” he ordered Carter.

The two Soldiers began to worry that they were the only Americans left alive, that some of the enemy’s unrelenting rounds would pierce the HMMWV’s much-weakened armor or that they’d have to crawl to the river and float to another American outpost. Worse, they could see Mace trying to crawl toward them, begging for help. Carter wanted to go to him, but Larson made him wait until the Apaches were overhead on a gun run. They patched him up as best they could and finally reached Bundermann on a squad radio Carter found. During a massive air and land bombardment that Romesha was at the forefront of, they grabbed Mace and ran for the aid station. They had been stuck at LRAS-2 all morning, but according to Larson, who immediately went to join Romesha at the shura building, that was the easy part of his day.

The hard part was recovering the bodies. Romesha led his men through open fire once again until they found Griffin, Martin and Gallegos. The barrage was so intense, that now-Staff Sgt. Armando Avalos had to use Gallegos’ body for cover. The two men were good buddies and he knew it was what Gallegos would have wanted, but it haunts him to this day. No one knew where Hardt was. Larson went to look for him, taking off all his gear so he could run faster, but Hardt wouldn’t be found until after the quick-reaction force arrived about sunset.

THE AFTERMATH

THE AFTERMATH

By the time Romesha learned a medical evacuation flight (MEDEVAC) was finally on the way for Mace (who had received five buddy-to-buddy blood transfusions, but would die anyway) and that he needed to clear the landing zone, Keating was in shambles. Many of the buildings had burned down, including the TOC, and others were piles of rubble. Shell casings lay everywhere and the bodies of insurgents lay scattered throughout the outpost.

The men had been fighting for 12 or 13 hours straight and they were exhausted, but there wasn’t time to process what had happened. They had to hold Keating for a few more days before they could finally leave the outpost, then they had to get through the second half of their deployment. The Army sent a psychologist to spend a lot of time with the men of Bravo Troop, to help them talk through the battle. That helped, but most of the men just shut off the pain, the fear and the grief until they got back to Fort Carson, Colo.

“We just kept on with our day-to-day business, bullshitting and laughing and joking around,” said Rasmussen. “I think we all just kind of suppressed it. There were still missions at hand and stuff that had to be done. For me personally, it didn’t register until I came back home, like that first week. That’s pretty much all I did, just sit there in amazement.”

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers