Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill in World War II wanted “specially trained troops of the hunter class, who can develop a reign of terror down these coasts [of occupied Europe], first of all on the butcher and bolt policy… leaving a trail of German corpses behind them.”

This translated into forming the British special forces. Here’s what Churchill got.

New tactics for new missions

The men who formed Britain’s special forces shared a particular sense of independence and ingenuity. Men like Orde Wingate, Roger Courtney, David Stirling and Ralph Bagnold wanted to find a new way of waging war. Gathering like-minded individuals around them, they trained for, planned and carried out their own operations. They developed new tactics for carrying out new missions.

READ MORE about Britain in World War II

They were helped by advances in technology that were happening at the time. Improved radio communication, better air and sea transport, more reliable motor vehicles, and hard-hitting new weapons and explosives made such warfare possible.

They also had a key supporter in Winston Churchill. The prime minister backed their plans when the military high command were often unenthusiastic. Keen to fight and win a conventional war, some generals considered special forces unnecessary ‘private armies’.

[Special Forces] trained, equipped and mentally adjusted for one kind of operation were wasteful. They did not give, militarily, a worthwhile return for the resources in men, material and time that they absorbed… They were usually formed by attracting the best men… The result was undoubtedly to lower the quality of the rest of the Army. This cult of special forces is as sensible as to form a Royal Corps of Tree Climbers and say that no soldier, who does not wear its green hat with a bunch of oak leaves stuck in it should be expected to climb a tree.’Field Marshal Sir William Slim, 1956

Climbing under live fire at the Commando Battle School, 1944

The Commando context

After the fall of France in June 1940, the British established a small, but well-trained and highly mobile, raiding and reconnaissance force known as the Commandos. The first recruits were volunteers selected from existing regiments in Britain. In 1942, the Royal Navy’s Royal Marine battalions were also reorganised as Commandos.

Commando recruits were trained at special centres in Scotland. They learnt physical fitness, survival, orienteering, close-quarter combat, silent killing, signalling, amphibious and cliff assault, vehicle operation, the handling of different weapons and demolition skills. Any man who failed to live up to the toughest requirements would be ‘returned to unit’.

The first commando operations were small raids. But later they grew both in complexity and size. As the Second World War continued, commandos fought in large formations as assault troops in many of the conflict’s key battles. But the need for smaller operations remained.

Cockleshell heroes

In December 1942, men from the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD) took part in a raid against German merchant vessels at Bordeaux. Several of the German ships there were known to be taking specialist equipment to Japan.

A large commando attack was ruled out as too expensive. Planners were also reluctant to launch an operation similar to the recent failed raid at Dieppe.

Instead, five two-man teams of the RMBPD disembarked from a submarine in the Bay of Biscay, tasked with paddling their folding canoes up the heavily-defended River Gironde. Only two teams made it to the port of Bordeaux. There they attached limpet mines to the ships, damaging six of them. The other canoes capsized in the rough waters near the Gironde estuary.

Of the ten men – who would later become known as ‘the Cockleshell Heroes’ – only two survived. Two succumbed to hypothermia and six were caught and executed. One of the survivors was raid leader Major Herbert ‘Blondie’ Hasler who escaped to neutral Spain.

Although the raid was a morale boost for the British population and the French resistance, it had little long-term strategic effect. Most of the damaged ships were soon back in use.

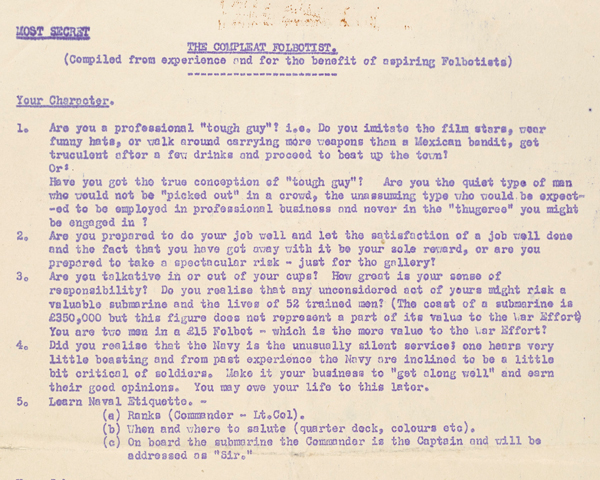

‘Are you a professional “tough guy”? Do you imitate the film stars, wear funny hats, or walk around carrying more weapons than a Mexican bandit, get truculent after a few drinks and proceed to beat up the town! Or have you got the true conception of “tough guy”? Are you the quiet type of man who would not be “picked out” in a crowd, the unassuming type who could expect to be employed in a professional business and never in the “thugeree” you might be engaged in? Are you prepared to do your job well and let the satisfaction of a job well done and the fact that you have got away with it be your sole reward, or are you prepared to take a spectacular risk just for the glory?’

Special Boat Section

Operating along similar lines to the RMBPD was the Special Boat Section. It was formed in July 1940 by Commando officer Captain Roger Courtney, who had formerly been a professional big game hunter in East Africa and had canoed the length of the White Nile.

His unit used folding canoes (or folboats) in a number of small-scale raids against railways, port facilities and airfields in Scandinavia and the Mediterranean.

Members of No. 2 Special Boat Section, including Roger Courtney (centre) at Hillhead, Hampshire, 1943

‘The Complete Folbotist’ by Captain Roger Courtney, written ‘from experience for the benefit of aspiring Folbotists’, 1941

Special Boat Section teams were made up of volunteers from across the three services. As well as raiding, they carried out beach reconnaissance, including missions for the cancelled invasion of Rhodes (1941), and the Operation Torch (1942), Salerno (1943) and Anzio (1944) landings in North Africa and Italy.

Often working with Lieutenant-Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Willmott and the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPP), they made sure beaches could be fully approached by landing craft and stand up to the weight of tanks and vehicles. This was another lesson learnt from the raid on Dieppe in 1942. They also inserted secret agents into enemy-occupied territory.

Boat teams later served in Burma, operating against the Japanese on the Chindwin and Irrawaddy rivers.

Special Air Service

The LRDG was augmented in July 1941 when commando officer Captain David Stirling established the Special Air Service (SAS), drawing its first men from No 7 Commando. This small raiding force targeted enemy airfields and port installations in North Africa, usually at night.

As with several other wartime special forces, there was no formal recruitment and selection process. Stirling often directly chose people he thought would be suitable. Other men put themselves forward.

Many had already undergone commando training, including Stirling himself, unit co-founder Lieutenant ‘Jock’ Lewes and Lieutenant Paddy Mayne, a former British Lions rugby player who later commanded the unit.

Today, SAS selection is far more formal and extensive. But the training introduced by Stirling and Lewes was still tough and included long marches with heavy loads.

Behind the lines

When Stirling’s men attempted to parachute on their first mission near Tobruk in November 1941, bad weather and inexperience led to disaster. Only 21 out of 50 men returned. The remainder were either killed or captured. The LRDG picked up the survivors.

From then on, until the SAS were issued with their own vehicles, the LRDG transported them behind enemy lines.

During their desert operations, the SAS destroyed more than 300 Axis aircraft. This was a cost-effective return on a handful of soldiers driving cheap vehicles maintained by a few mechanics.

Paddy Mayne’s personal tally of destroyed aircraft was higher than any Royal Air Force fighter ace.

For the rest of the series, visit the British National Army Museum

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers