Washington Guard helped defend US after Pearl Harbor attack

By Joseph Siemandel, Joint Force Headquarters – Washington National Guard

CAMP MURRAY, Wash. – As the sun rose Dec. 7, 1941, U.S. military personnel stationed at Pearl Harbor Naval Base were starting their Sunday routines. Unknown to them, more than 350 Imperial Japanese bombers, fighter and torpedo planes launched from six aircraft carriers in two waves with their eyes set on the base just outside Honolulu.

A day that will live in infamy, the attack propelled the United States and President Franklin Roosevelt to declare war on Japan and officially enter World War II.

This one event may have been the tipping point, but the U.S. military had already begun preparing for an attack on the mainland. Ten months before the events on Pearl Harbor, two Washington National Guard units, the 205th and 248th Coast Artillery Regiment, had been called into federal service at North Fort Lewis to begin training on a highly important mission that would span the course of World War II and beyond.

The 205th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-Aircraft)

The 205th Coast Artillery Regiment (Anti-Aircraft) and 248th Coast Artillery Regiment (Harbor Defense) were called into service Feb. 3, 1941, to train on what would be a four-year mission of protecting the West Coast and Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle.

In June 1941, the units began mobilizing across the West Coast and parts of Alaska. Battery E, 205th Coast Artillery, set sail from Seattle for Seward, Alaska. In July, two additional batteries of the 205th joined them as part of the defense of the Northwest Passage, a waterway connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans near the Arctic Circle.

On Oct. 29, 1941, the War Department directed the remaining units of the 205th Coast Artillery to move to Camp Haan, near Los Angeles. The unit arrived for duty Nov. 22, 1941, only two weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

After more than two years of service in Southern California, the 205th went through a number of reorganizations. Some units split off and were assigned to other commands. One such unit was the 530th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Weapons Battalion (AAAW BN) (originally 2nd Battalion, 205th Coast Artillery), which mobilized to Greenock, Scotland, in December 1944. The 530th AAAW BN was reassigned to the 15th Army and moved to Germany in April 1945 before returning to New York City for deactivation on Halloween 1945.

Battle of Los Angeles

On the night of Feb. 24, 1942, just three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, air raid sirens sounded throughout Los Angeles County, signifying an attack was imminent. A blackout was ordered, and thousands of air raid wardens were summoned to their positions.

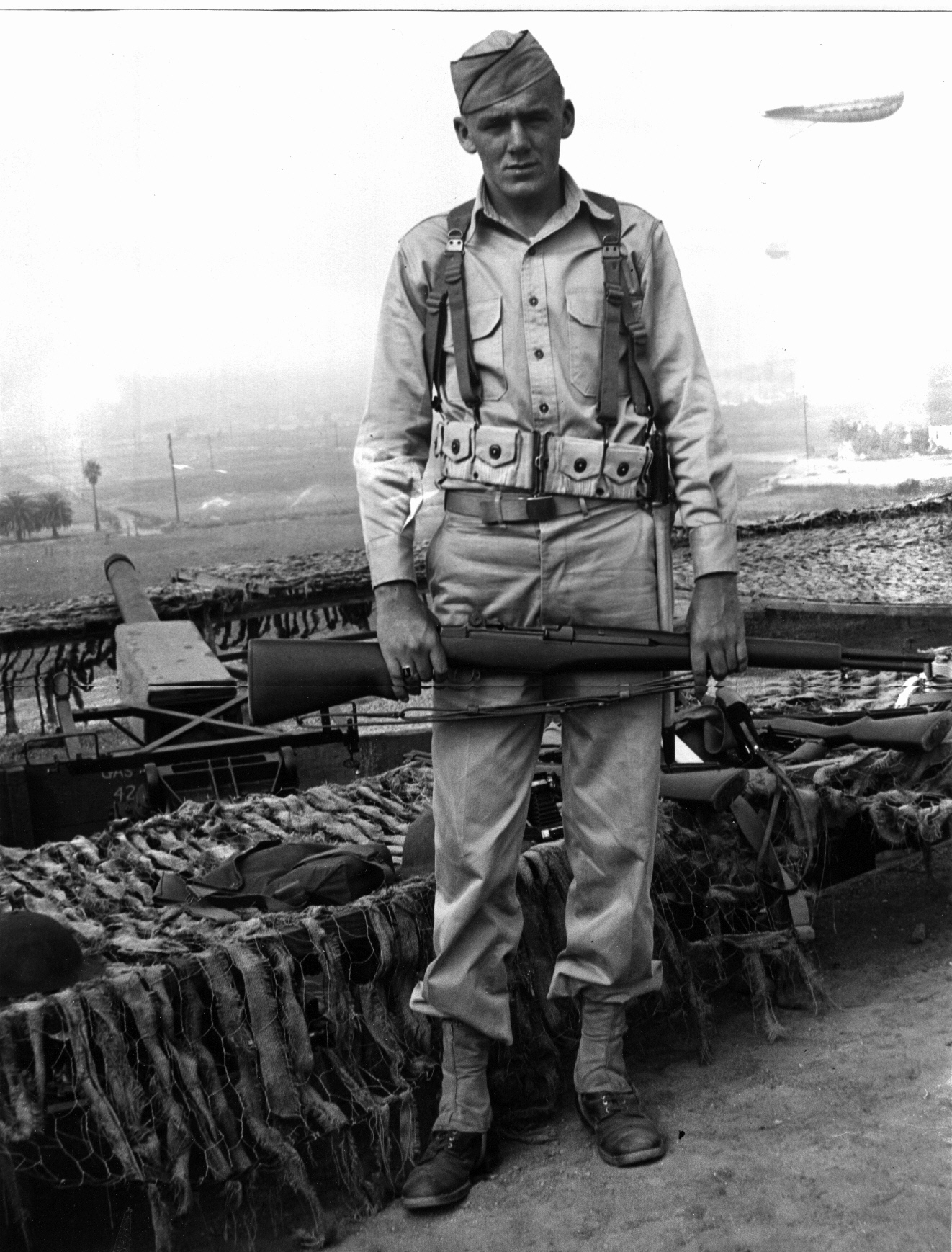

Washington National Guardsmen from the 205th Coast Artillery assigned to the 37th Coast Artillery Brigade took their positions in the dark, preparing to defend their country from another attack.

Then at 3:17 a.m., the Guardsmen began firing their 50-caliber machine guns and 12.8-pound anti-aircraft shells into the air at reported aircraft. More than 1,400 shells were launched in the next hour. When the “all-clear” was given at 7:21 a.m., several buildings and vehicles had been damaged by shell fragments.

Within hours of the end of the air raid, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox held a news conference, saying the entire incident was a false alarm due to anxiety and “war nerves.” A statement by the Army the following day claimed the incident might have been caused by commercial airplanes used as a psychological warfare campaign to generate panic.

Speculation was rampant about invading airplanes and their bases. Theories included a secret base in northern Mexico and Japanese submarines stationed offshore with the capability of carrying planes. Others speculated the incident was staged or exaggerated to give coastal defense industries an excuse to move further inland.

In 1983, the Office of Air Force History concluded meteorological balloons caused the initial alarm.

The 248th Coast Artillery Regiment (Harbor Defense)

The 248th Coast Artillery Regiment (Harbor Defense) was called into active federal service by presidential proclamation Aug. 31, 1940.

One of the original field artillery units of the 2nd Infantry, Washington National Guard Regiments, the 248th was used to federal activations. Organized into 12 companies of coast artillery, the 248th was ordered into federal service by the president on July 25, 1917, and assigned to duty at the harbor defenses of Puget Sound.

As coastal artillery become more important after World War I, the 248th added three more companies in Aberdeen, Snohomish and Olympia. With the addition of the 205th Coast Artillery Regiment in 1939, Washington had two units focused on the defense of the coastlines against enemy aircraft.

On Sept. 1, 1940, the 248th Coast Artillery was organized by combining the 1st Battalion and Regimental Headquarters Battery, 248th Coast Artillery. On Sept. 16, 1940, the 248th Coast Artillery (HD) was inducted into federal service at the home station of the respective batteries and concentrated at Fort Worden, Washington. The entire 248th Coast Artillery was relieved of harbor defense duties and transferred to Camp Barkeley, Texas, leaving Fort Worden, on April 25, 1944.

Another Take:

The Battle of Los Angeles

Published by Greg Lucas

On the evening of February 24, 1942, an anti-aircraft barrage of more than 1,440 rounds is launched at what is initially thought to be a Japanese aerial attack on the City of Angels. Five civilians die – three from traffic accidents spawned by the chaos and two from heart attacks.

What, if anything, is being fired upon remains a mystery. Theories include weather balloons, UFOs, birds, or just jitters by Angelenos with Pearl Harbor still a fresh memory and, even fresher, a Japanese submarine torpedoing a Santa Barbara oil field on February 23.

Regardless of cause, air raid sirens first blare at 7:18 p.m. Thousands of air raid wardens go to their posts throughout Los Angeles County. That alert is lifted at 10:23 p.m. Tensions ease. Then, after midnight, all hell breaks loose. From “Chapter 8: Air Defense of the Western Hemisphere” by William Goss, The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. 1 published in 1983:

“Radars picked up an unidentified target 120 miles west of Los Angeles. Antiaircraft batteries were alerted at 2:15 am and were put on Green Alert—ready to fire—a few minutes later. The (Army Air Force) kept its pursuit planes on the ground, preferring to await indications of the scale and direction of any attack before committing its limited fighter force. Radars tracked the approaching target to within a few miles of the coast, and at 2:21 am the regional controller ordered a blackout. Thereafter the information center was flooded with reports of ‘enemy planes,’ even though the mysterious object tracked in from sea seems to have vanished. At 2:43 am, planes were reported near Long Beach, and a few minutes later a coast artillery colonel spotted ‘about 25 planes at 12,000 feet’ over Los Angeles. At 3:06 am a balloon carrying a red flare was seen over Santa Monica and four batteries of anti-aircraft artillery opened fire, whereupon ‘the air over Los Angeles erupted like a volcano.’ From this point on reports were hopelessly at variance.”

Not the least at variance are the media reports. According to theLos Angeles Herald Examiner a witness puts the number of planes at 50. Three are shot down over the ocean. A battery near Vermont Ave. takes out another. “Air Battles Rages Over Los Angeles” is the headline of the Examiner’s “War Extra.” The normally more staid Los Angeles Times says:

“Roaring out of a brilliant moonlit western sky, foreign aircraft flying both in large formation and singly flew over Southern California early today and drew heavy barrages of anti-aircraft fire – the first ever to sound over United States continental soil against an enemy invader.”

In Washington D.C., Navy Secretary Frank Knox says: “As far as I know the whole raid was a false alarm and could be attributed to jittery nerves.” Secretary of War Henry Stimson says 15 unidentified aircraft were over Los Angeles — possibly commercial aircraft operated by the enemy from secret fields in California or Mexico or light planes launched from Japanese submarines. Their goal is to determine the location of anti-aircraft defense or damage civilian morale, Stimson says.

Returning to The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. 1:

“Probably much of the confusion came from the fact that anti-aircraft shell bursts, caught by the searchlights, were themselves mistaken for enemy planes. In any case, the next three hours produced some of the most imaginative reporting of the war: “swarms” of planes (or, sometimes, balloons) of all possible sizes, numbering from one to several hundred, traveling at altitudes which ranged from a few thousand feet to more than 20,000 and flying at speeds which were said to have varied from “very slow” to over 200 miles per hour, were observed to parade across the skies. These mysterious forces dropped no bombs and, despite the fact that 1,440 rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition were directed against them, suffered no losses.”

After the war, Japan says it has no planes in the area at the time of the “raid.” The Army Air Forces in World War II, Vol. 1 posits weather balloons as the most likely explanation. A photo from the Los Angeles Times has been used to “prove” it is an extraterrestrial craft. Another explanation appears in an article attributed to the veteran Los Angeles newsman Matt Weinstock in which he interviews a man who says he served in one of the anti-aircraft batteries:

“Early in the war things were pretty scary and the Army was setting up coastal defenses. At one of the new radar stations near Santa Monica, the crew tried in vain to arrange for some planes to fly by so that they could test the system. As no one could spare the planes at the time, they hit upon a novel way to test the radar. One of the guys bought a bag of nickel balloons and then filled them with hydrogen, attached metal wires, and let them go. Catching the offshore breeze, the balloons had the desired effect of showing up on the screens, proving the equipment was working. But after traveling a good distance offshore and to the south, the nightly onshore breeze started to push the balloons back towards the coastal cities. The coastal radar’s picked up the metal wires and the searchlights swung automatically on the targets, looking on the screens as aircraft heading for the city. The ACK-ACK started firing and the rest was history.”

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers