by Susan Katz Keating

It was the largest amphibious assault in the history of warfare, and one of the most decisive military missions of modern times. The outcome of WWII rested upon the success of D-Day – a mission that was long in the making, and shrouded in secrecy until the moment it launched.

Soldiers, unit histories, and historians tell a story that offers a glimpse of the intensity of D-Day.

Soldiers knew few details of their forthcoming mission, other than how important it was. As time progressed, the men were sequestered inside camps protected by barbed wire fences. They had no contact with people on the other side.

“There was a fence all around us,” according to H.L. “Pete” Myers, who was the last survivor of his unit before he died in 2017 at the age of 94. “None of us could get in or out. We couldn’t talk to nobody, and nobody talked to us.”

When D-Day arrived, the men boarded the ships that would carry them to their rendezvous with history. Loudspeakers delivered their commander’s Order of the Day.

“The eyes of the world are upon you,” General Dwight D. Eisenhower told them. “The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.”

The relatively short journey across the channel from England to France was impossibly rough.

“The water was coming all over,” Myers remembered. “The boats were bouncing up and down and the boys were getting seasick, vomiting in their helmets and putting (them) back on; it would run all down their face(s) and shirt(s).”

Many were dehydrated and weakened.

“They were given apples and bananas to try to get them to survive for the beach,” Myers said.

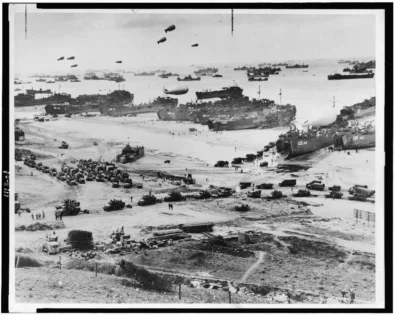

A bird’s-eye view of landing craft, barrage balloons and Allied troops landing in Normandy, France, on D-Day, June 6, 1944. U.S. Maritime Commission photo.

One boat, which ferried the command group, fell genuinely afoul of fate. While being lowered into the sea, the command boat became lodged beneath the mother ship’s sewage pumps. The pumps bombarded the men with human excrement for nearly 30 minutes.

“We cursed, we cried and we laughed,” recalled Major Thomas S. Dallas, executive officer of the 1st Infantry Battalion, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, in an interview with Army historians. “But it kept coming.”

Elsewhere, men boarded their landing craft by climbing down the sides of ships via cargo nets. Each soldier carried about 90 pounds of gear. Some men were tossed into the water and vanished. Those who made it into the small Higgins landing craft settled in for the final horrific journey into fire.

“Waves broke high over the boats, and all personnel had to turn to and bail fast with their helmets to keep the boats afloat,” Dallas told historians.

The landing force was pulled off course by powerful tides. The 116th missed most of its assigned landing spots.

“It was a struggle simply to reach the objective,” one historian said. “And then they had combat.”

A report compiled by Army historians shortly after D-Day described the chaos.

“The first ramps were dropped at 0636 in water that was waist-deep to over a man’s head,” reads the report. “As if this had been the signal for which the enemy waited, the ramps were instantly enveloped in a crossing of automatic fire which was accurate and in great volume.”

Soldiers crumpled while trying to exit the boats. Some tried to avoid the gunfire by diving head first into the water, according to the report. There, they fought to keep from being dragged down by their gear.

“In one of the boats, a third of the men had become engaged in this struggle to save themselves from a quick drowning,” recalled Private First Class Gilbert G. Murdock.

Many were hit while in the water. Others reached the beaches only because the man in front caught a bullet and spared them from being hit.

Another Army report reads: “Others, wounded, dragged themselves ashore and upon finding the sands, lay quiet and gave themselves shots [of morphine], only to be caught and drowned within a few minutes by the on-racing tide.”

The seas took vital equipment. The enemy shot out the pontoons that kept amphibious tanks afloat. These and other seaborne tanks foundered and sank.

One veteran, John L. Glaser, recalled trying to send howitzers ashore aboard a 6-wheeled DUKW landing craft (the amphibious modification of the 2 and a half-ton capacity “deuce” truck).

“As soon as the howitzers were placed onto the ‘Duck’ the boats began to sink,” Glaser said. “You could hear the men hollering and we were lucky to save their lives.”

Glaser’s team lost 11 of their 12 howitzers.

Despite the heavy losses to men and equipment, scores rallied and pressed on in the face of withering opposition.

Glaser was racing headlong across the sand toward enemy positions when his beachmaster hollered for him to stop. Glaser was in the middle of a minefield.

He recalled telling his beachmaster: “Sir, I am petrified and can’t move.”

As reports indicate, the beachmaster walked forward across the sand in Glaser’s footprints and pulled the terrified Soldier back through the same prints to safety.

The nonstop onslaught from German gunners tore through the Americans. Wave after wave of men were blown to pieces for hours on end. The intrepid Soldiers fought on. One group scaled a cliff so as to knock out an enemy position. The men then spent the entire day fighting some 70 Germans before claiming victory on one fortified site alone.

The enemy was not the only source of incoming fire. An Allied destroyer mistook Dallas’ group for Germans, and shelled it until early evening, when a beachmaster managed to reach a Navy radio and call off the destroyer.

Norman “Dutch” Cota

In the thick of battle, with Americans pinned beneath enemy fire on Omaha, the 29th’s General Norman “Dutch” Cota took action to free his men. The 51-year-old commander stood upright amid the firestorm, puffing a cigar, telling the soldiers to get off the beach.

Cota tasked some soldiers with blowing a hole through a wire fence that trapped the force inside the kill zone. Cota raced through the freshly opened gap, leading the way for others to follow. He proceeded to the village of Vierville-sur-Mer, where he awaited his soldiers. He greeted them with a shout: “Where the Hell have you been, boys?”

By the time night fell on D-Day, Operation Overlord was a decisive success. The Allies took the day, capturing all five landing sites.

But the war was far from over. In the hours and days following, Allied forces continued to assault Normandy, and remained in combat until Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945—forever to be known as Victory in Europe (V-E) Day.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor in chief at Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers