Wilford was sent by his superiors into a complex and profoundly violent situation because they believed he was right for the job. His Majesty’s Armed Forces should acknowledge as much about one of their own.

COMMENTARY by Susan Katz Keating

Quietly over the weekend, a locally infamous British Army officer died at the age of 90 in Belgium. A figure from a complex and difficult time, Col. Derek Wilford was known throughout Ireland and the United Kingdom as the man who commanded the Parachute Regiment on Bloody Sunday, when 13 civilians were shot dead in Derry, Northern Ireland. Wilford’s men revered him, but he became such a lightning rod that his own military announced his death in a way that did a disservice to him and to the Army – and also reminded me of the treacherous landscape I saw as a schoolgirl in Ireland during those dark times.

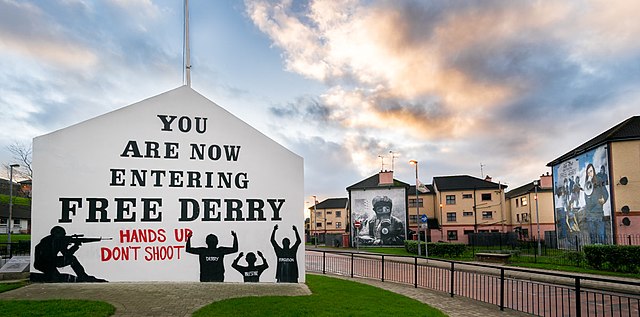

In the leadup to Bloody Sunday 1972, the British-ruled province of Ulster (AKA Northern Ireland) was consumed by conflict. In overly simple terms, it was a guerrilla war between Irish nationalists and British loyalists, split along sectarian lines. The mostly Roman Catholic nationalists wanted Northern Ireland to unite with the Republic of Ireland, while the mostly Protestant unionists wanted it to remain in the United Kingdom. In practise, it was a byzantine weave of violent factions and sub-factions, replete with retribution, conflicting internal aims, and intrigue.

The struggles within Ulster condensed into a cauldron of kidnappings, bombings, “disappearings,” gunbattles, and assassination. There emerged one intensely violent anti-British group: the “Provos,” the outlawed Provisional Irish Republican Army.

READ MORE Commentary from Soldier of Fortune publisher Susan Katz Keating

In the summer of 1971, the Provos ramped up their campaign inside Ulster. That August, British forces launched a pre-dawn raid, and rounded up the first of nearly 2,000 men suspected of belonging to the IRA. The suspects were held without trial at Long Kesh prison in County Antrim.

In December of that year, I moved with my mother to Dublin. My family warned me, do not under any circumstance go “up North.” I wanted to see what was going on, but initially I remained in the south.

Violence continued to escalate. Each incident sparked outrage. In Belfast, Unionist paramilitaries detonated a bomb at McGurk’s Bar, killing 15 Catholic civilians. In Derry, shootings and days-long riots roiled the city. An IRA sniper shot and killed a British soldier. Off-duty teenage British soldiers were lured from a pub and murdered. On and on it went.

Against that background, a civil rights group announced that it would defy a security ban against marches. The group said it would stage a march through Derry on Sunday, January 30.

Authorities in Ulster believed that the march would bring a violent response from unionists, but allowed the event to proceed. Officials decided to bring in security, in the form of the British Army.

“The march was expected to be too large for the police to be able to control it themselves, so the Army shouldered the main burden of dealing with it,” according to a British government inquest that concluded in 2010. “The plan that emerged was to allow the march to proceed in the nationalist areas of the city, but to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square,” the site of a significant battle in 1689. The date is not a typo: the battle took place in 1689.

Officials brought in an arrest force from Belfast. That unit was the 1 PARA, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford. The unit traces its lineage to World War II, including action in Tunisia and as part of Operation Market Garden. It was heavily involved in Northern Ireland. In the summer of 1971 and in January 1972, the unit was embroiled in high profile and controversial gunbattles, and was accused of brutality. Nevertheless, the unit was sent to Derry on January 30.

The day would become one of the most hellish of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

Soon after the march began, riots broke out at various places along the route. Barely an hour into the event, soldiers from 1 PARA opened fire, shooting 26 people. Thirteen were killed.

Chilling questions emerged. Did the soldiers shoot without cause? Did the marchers deliberately start the confrontation by throwing rocks and bombs? Was the whole thing a set-up? Everyone had wildly conflicting theories, and impassioned opinions.

Over the decades, journalists and officials looked for the truth.

Investigations brought details to light. Among them: The marchers hurled rocks and missiles at soldiers; the IRA had sent snipers to shoot British soldiers; rioters and soldiers fired CS gas at one another; and British soldiers shot civilians. According to reports, some of the civilians tested positive for firearms residue. One was found to be carrying nail bombs. Others were unarmed.

The initial government investigation largely cleared the soldiers of blame.

A second British government inquest took place over the course of 12 years, and found that the soldiers were at fault.

In 2010, then-Prime Minister David Cameron told the House of Commons: “What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong.” He said the conclusions were “absolutely clear” and there were “no ambiguities.”

Derek Wilford, though, insisted to his dying day that his soldiers had been fired on first, and acted appropriately.

Myself, I don’t know what happened. I wasn’t in Derry that day.

I was, however, in Dublin a few days later, when an outraged crowd sought retribution for Bloody Sunday. On one very dark February night, some 25,000 people laid siege to the British Embassy. I watched from the top of a lamppost while seemingly normal people brutally beat unarmed police, hurled petrol bombs, burned down the embassy, and cut the water hoses when fire crews tried to respond.

That event also began as a protest march. No one was shot. No one was killed. But from my perch atop the lamppost, I saw vicious fights that spiraled exponentially. I couldn’t tell who started any of them. I watched them unfold in real time, but I saw no direct lines between cause and effect and culpability. Such is the nature of chaos. And this event was far more contained than what happened on Bloody Sunday.

What, then, of Wilford, who said his men were scapegoated, and who lived his final days in exile in Belgium?

Derek Wilford. Photo from British Forces Net.

When the British Forces Broadcasting Service announced that Wilford had died, the network gave weight to the notion that the officer left a “terrible legacy.” The network quoted people denouncing him, and no one offering context or balance.

Both are important.

Part of the context is, the British Army in 1972 sent 1 PARA to Derry because the unit was tough. The Provos and many nationalists viewed them as “butchers,” while others took that same view of the Provos. I am told there was rivalry in Northern Ireland between British Army commanders, which contributed significantly to the dynamic that day; but the bottom line is, the Army sent 1 PARA to Derry for Bloody Sunday.

The British Forces network left out the observations of former BBC journalist Peter Taylor, who told BBC radio, “Derek Wilford was adored by his men.”

The network left out comments from soldiers in Wilford’s command. “He was always with us on the front line and this boosted our confidence,” one soldier said.

The network left out this statement from Wilford, regarding what he told his men that day: “I warned them all to keep their heads down and to fire only at identifiable targets.”

Those were nightmarish times in Ireland, and the legacy continues.

People still talk about Bloody Sunday. They talk about Shergar, McGurk’s Bar, the Long Kesh prison, internment without trial, the Battle of the Bogside, and events going back to 1689. To a lesser degree, they talk about the night the British embassy was gutted in Dublin.

They talk about Derek Wilford. The consensus is, he is to blame for Bloody Sunday. His own military now supports that view. A broader perspective would show that Derek Wilford was a soldier, sent by his superiors into a complex and profoundly violent situation because they knew who he was and how he rolled. They believed he was right for the job.

His Majesty’s Armed Forces should acknowledge as much about one of their own.

Susan Katz Keating is the publisher and editor in chief of Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers