by Marvin J. Wolf, The War Horse

Tall, muscular, broad-shouldered, with a full head of white hair, Brig. Gen. John M. Wright Jr. scrambled up a termite mound, some 30 feet wide at the base and seven or eight feet high, and gestured for us to draw into a semicircle.

“Gentlemen, I give you the termite,” said Wright, parade-ground volume. He bent to scoop something up, then waved it aloft. “Half an inch long, blind, unable to hear or speak. Yet termites built this mound.”

He paused to let that sink in. “Termites succeed because they are many and they work almost without rest. Gentlemen, for the next 28 days, we will become termites.”

READ MORE about American soldiers at war in Vietnam

Wright pointed across the dirt airstrip where a day earlier we had landed in C-130s. “Triple-canopy jungle,” he said. “Big trees about 200 feet high. Then secondary growth up to about 80 feet. Under that, bamboo, thorn thickets, shrubs, and vines. And beneath all that is grass—turf. If we could magically pluck out all that foliage, it would look like a golf course.

“The ships with our 437 helicopters will reach Qui Nhon harbor in about four weeks. They’ll need a place to land. They’ll need to disperse; once Charlie finds out who we are, he’ll come after them.”

Wright pointed to the jungle again. “Here we will build the largest helicopter field in the world. We have hand tools and a few flamethrowers. We have explosives and we have a couple of jeeps with winches.

READ MORE about a flamethrower in civilian life

“It would be easier to bring in bulldozers and knock everything down. That’s how the Foreign Legion built this strip. But look at the ground. Mud. Before noon it will be dust.”

Wright mopped his forehead with a big red handkerchief. It was 0700 but already close to 100 degrees. “If we scrape away the jungle with bulldozers, in a month we’ll have a giant dust bowl. That dust will be sucked into helicopter engines and turbines. This is the end of the longest supply line in the world. Every turbine blade, air filter, every fuse—every spare part—has to travel 12,000 miles. If our heliport is a dust bowl, we’ll wear out our ships faster than we can fix them.

“So we’ll create a golf course. Chop down the trees, pull out the bushes and cut the bamboo, elephant grass, and the wait-a-minute vines—but leave the turf.

“I know that this is a lot to ask of you,” he continued. “I also know that we can do it. In 1942, I was a prisoner of war. The Japanese forced me, my men, and the other survivors of Corregidor to build airfields on Luzon with nothing but mess spoons and our bare hands. And we built them—we had no choice.”

I looked into that foreboding jungle, vibrating with the hum of millions of insects and the screeching of birds and monkeys. The night before it had echoed with the soft grunt of wild boars and the distant trumpeting of an elephant. A tiger added its distinctive cough to the nocturnal cacophony and announced residence with fresh pugmarks in the riverbank mud.

Someone walked on my grave, and I shuddered.

There was another reason why we wouldn’t use bulldozers. A few weeks earlier, President Lyndon Johnson had announced that he was sending us, the First Air Cavalry Division, to Vietnam. We didn’t like having our departure telegraphed, but at least he didn’t say where we would be based. Once we started building an enormous heliport, however, the enemy would know. Our intelligence told us that major elements of at least two North Vietnamese divisions roamed these mountains, perhaps within striking distance. We could only hope that our intentions would remain secret until the rest of our troops arrived. Meanwhile, we were a relatively small, lightly armed advance party of 1,040. Bringing in earthmoving equipment would pinpoint us as a target before we were strong enough to defend ourselves.

Wright removed his fatigue jacket and tied it around his waist. He rolled his red handkerchief into a sweatband and tied it around his head.

“Questions?”

A thousand questions hung in the heavy, humid air. None found a voice.

“Let’s go build a heliport,” said Wright. He slid down the termite mound, then turned to an aide, who handed him a long machete. He looked around. He looked right at me. “Follow me,” he said and marched into the jungle.

We followed.

Most of us were field-grade officers—majors and colonels—or senior noncoms, the ranks that make up an advance party whose usual mission is to guide incoming units to their new locations. We also had a rifle company to help protect us. In the surrounding hills, a battalion of the 101st Airborne patrolled the valley’s approaches.

I was a private first class. Along with Maj. Charles Siler, the information officer; and Specialist Four Joe Treaster, a former Miami Herald reporter, we came to document Operation Golf Course. But we would not sit around while hundreds of senior officers and noncoms were breaking their balls. Note-taking and photos were squeezed into evenings and rest breaks.

Days and nights settled into an exhausting routine. Reveille at 0500. Cold C-rations at 0530. Work call at 0630. By 0700 we were deep in the jungle, where we worked straight through with five-minute breaks each hour. At noon we paused for 30 minutes to eat. Work resumed until 1800. We returned to our tents for a third cold meal. Then we rinsed underwear in steel helmets and cleaned rifles. White light was banned at twilight, cigarettes doused, a guard mounted to patrol inside our flimsy barbed wire. Everyone below colonel pulled two hours of guard duty every other night. As we slept, legions of marauding mosquitoes harvested our blood.

And then we got up and did it all over again.

When I was a kid in Chicago, my dad was a junkman. In the late 1940s when I was still in single digits, many of Chicago’s older homes switched from coal-fired furnaces to oil burners; in the summer, homeowners hired Dad to haul away their old cast-iron furnaces. Dad found a helper and we drove to the suburbs. Those old furnaces were massive, double-walled cast iron. Fire heated water circulating between the walls. The furnace was swathed in insulating brick or concrete. With a sledgehammer and crowbar, the men removed the insulation. Then Dad knocked the furnace door off its hinges and hoisted me inside. My job was to bang on the furnace’s inner ribs with a small hammer until, one by one, they cracked from metal fatigue.

Swinging a hammer inside a furnace in an airless basement was like being trapped in an oven and trying to batter your way out. The heat, noise, and exertion were overwhelming. When Dad finally hauled me out, coughing and choking, I was ready to drop from exhaustion and filthy with sweat mixed with ash and soot. While I caught my breath, Dad and his worker stood three or four feet apart and attacked the furnace with nine-pound sledge hammers until it collapsed. Then I helped separate chunks of cast iron from brick and ash destined for the dump. At the end of each long, hot, excruciating day, I was too exhausted even to eat.

I thought about those old furnaces as I worked. I was older and stronger, but the termite’s day was far worse even than busting iron with a hammer. We had only a few dozen axes and 300 machetes, so most of us made do with personal hunting knives or entrenching tools. Both were ineffective against thorn but somewhat useful on bamboo and saw-toothed elephant grass. Big trees came down with axes and a single crosscut saw one noncom had thought to buy before we left Fort Benning. The few monster trees, mostly banyans, came down with blocks of C4, which we also used to level hundreds of termite mounds and anthills studding the jungle floor.

After a few days, a major hitched a ride to Qui Nhon and came back with four small, gas-powered chainsaws to cut young trees and trim big limbs from felled giants. But with almost constant use and no spare parts, by the third week, all were inoperative. We dug small stumps out with spades and crowbars. Larger ones were dragged out with steel cables and jeep winches. The biggest stumps, from massive, centuries-old trees, were blasted out with C4.

We had a few flamethrowers, but nothing to thicken gasoline for the stream to reach deep into a thicket. At best they helped disperse some of the frightening numbers of insects that attacked every inch of exposed skin. They were also useful for setting fire to the felled vegetation, much of it damp, that we dragged into huge piles.

To add a measure of competitive interest to our labors, teams were formed. Groups of senior officers, junior officers, noncoms, and enlisted men below sergeant competed. We tracked progress on a chalkboard: numbers of trees felled, stumps removed, and acreage cleared. I remember pausing at the board one noon, trying to find some satisfaction in the rows of neatly written figures—but the jungle remained a vast, brooding presence oblivious to our sweat and agony.

Until then, officers had seemed remote, Olympian figures, infrequently seen and rarely spoken to, a breed apart from the rough-hewn noncoms that to an ordinary soldier appeared to run things. Now, working and living among a large group of officers, I saw them as men. But not ordinary men. They were educated and erudite, dedicated, and courageous. They worked as hard and as long as any man. Men with doctorates, men who flew helicopters, men entrusted with the very lives of hundreds wielded axes and machetes. No one who followed Gen. Wright into that jungle could fail to admire our officers.

After a week everyone had blistered hands, small cuts and welts, and myriad insect bites. A doctor and three corpsmen held sick call twice daily, dispensing antiseptics, bandages, and occasional tetanus boosters and antibiotics. Even so, many cuts became infected. With no place to wash our clothes, undershorts began to rot. Our crotches chafed raw from constant movement, and everyone suffered from fungus infections and world-class varieties of athlete’s foot.

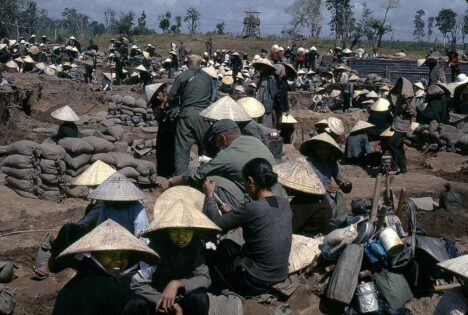

After three weeks, a small Viet Cong unit attacked us. Now that our presence was known, we hired hundreds of local people to help us. Two days before our helicopters arrived, we had cleared enough jungle to disperse them all. Most of the turf remained intact, as Gen. Wright had planned.

I still take pride in being among those who created the world’s largest heliport. In the years since, cheap, shoulder-fired, heat-seeking anti-aircraft missiles have radically changed the battlefield; it’s unlikely that any army will ever again assemble so many helicopters in one place. There will never be a larger heliport than the one I helped build.

My contributions were modest. Yet I cherish the feeling that if I never accomplish anything else, I was part of something extraordinary, and I learned that there is very little men can’t accomplish if they are willing to toil like a swarm of blind, mute insects.

Editors Note: Marvin J. Wolf served 13 years on active duty with the US Army, and has written number of books. This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers