Location: Tay Ninh, Vietnam. Photographer: SP5 Glenn Ramussen, Pictorial A-V Platoon, 69th Signal Battalion (A).

KING OF BATTLE: U.S. ARMY’S FIeld Artillery in Vietnam

By Boyd L. Dastrup Army.mil

The Vietnam Years

While the Army modernized its field artillery, a crisis in Southeast Asia attracted American attention. After eight years of fighting to preserve its colonial empire, France finally suffered defeat at the hands of Ho Chi Minh, an ardent Vietnamese nationalist and communist, when Dien Bien Phu fell in March 1954. This along with communist rhetoric about picking up the banner of nationalism by supporting wars of liberation influenced the United States to consider sending troops. Provisional agreements reached at Geneva, Switzerland, prevented this, divided the country at the seventeenth parallel, and scheduled reunification to come through a general election in July 1956.

Fearing that the communists would eventually gain power, the United States began pouring in economic and military aid to buttress South Vietnam against subversion by the Viet Cong, a con- traction of Vietnamese Communists, and the threat of invasion by North Vietnam. Although the Army had been sending advisors to Vietnam since the early 1950s, President John F. Kennedy’s decision in the spring of 1961 to increase the American commitment greatly expanded the Army’s advisory effort. As quickly as the Army could train advisory teams, it dispatched them to South Vietnam. Each field artillery advisory team included an officer, generally a captain, and a senior noncommissioned officer and was assigned to an artillery battalion in South Vietnamese divisions and corps. While the officer provided guidance to improve overall unit effectiveness, the noncom- missioned officer assisted the battalion operations officer and operations noncommissioned officer in training firing batteries and gun sections. In the meantime, an American artillery officer, normal- ly a major, was assigned to each corps and division to counsel senior South Vietnamese comman- ders on artillery matters and coordinatc the efforts of the advisory teams in subordinate battalions. Although the Americans faced soldiers with a different set of values, they produced a better led and trained South Vietnamese artillery by 1965 than the one encountered in 1961.

In the meantime, North Vietnam built a military force to gain control of Vietnam. By the early 1960s North Vietnam had a formidable army that had been organized, equipped, and trained along Chinese lines and that relied upon stealth and foot mobility. North Vietnamese divisions had around ten thousand lightly armed and equipped men with a ready reserve of approximately five hundred thousand men. To compensate for the lack of firepower the North Vietnamese stressed rigorous discipline, tactical superiority, and careful preparation. The Viet Cong gave the North Vietnamese another tool to bring down the South Vietnamese government by infiltrating South Vietnam and conducting sabotage, terrorist, and propaganda campaigns.

Encouraged by the deaths of Ngo Dinh Diem, the premier of South Vietnam, and President Kennedy, North Vietnam intensified its political and military offensive against South Vietnam in

1964.

To meet the external threat the Army abandoned its defensive strategy for aggressive offensive actions.54 After a series of limited offensives, General William Westmoreland, Commander, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, opened a campaign to counter North Vietnamese moves to cut South Vietnam in half. After an attack on a special forces camp at Plei Me in October 1965, he sent the 1st Air Cavalry Division (Airmobile) under Major General Harry W.O. Kinnard to destroy the retreating North Vietnamese units responsible for the assault.

Late in October 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division moved into the Ia Drang Valley. After several days of searching, the 1/9 Cavalry bumped into the enemy on I November. As the fighting grew hotter, the 1st Cavalry quickly concentrated by using the helicopter’s mobility, defeated the North Vietnamese, and forced them to retreat. That same day, 1/9 Cavalry’s airborne scouts spotted a battalion-size enemy force advancing towards the recent fight. The scouts fired on the North Vietnamese. Without any artillery support the 1/9 Cavalry along with reinforcements airlifted into the battle area repeatedly repulsed enemy assaults. The enemy’s proximity to American troops precluded aerial artillery from being employed, while tube artillery was out of range. On 3 November the 1/9 Cavalry squadron began conducting a reconnaissance-in-force along the Cambodian border. After establishing a patrol base, it staked out ambushes to catch North Vietnamese units fleeing to safety. That night the North Vietnamese ferociously hit the 1/9 Cavalry. Aerial artillery and a dogged defense turned back many enemy attacks. Outside of aerial artillery, the 1st Cavalry’s field artillery provided minimal support. The short, intense battles fought at distances beyond towed artillery’s range simply precluded any help.

During the second week of November, both sides opened offensives to gain control of the la Drang Valley. On 14 November CH47 Chinook helicopter airlifts placed two batteries at Landing Zone t .con to support the 1/7 Cavalry’s offensive at Landing Zone X-Ray. Gun crews concentrated their fire around the landing zone. As tube artillery lifted its fire, aerial artillery blasted the area to allow the infantry to land. This action totally disrupted North Vietnamese plars to attack Plei Me and put them on the defensive. Even though they were surprised, the North Vietnamese slugged the Americans viciously with small arms, rocket, and mortar f.:e. To repel the assaults the Americans airlifted in reinforcements throughout the day under the cover of artillery fire from L-.nding Zone Falcon. These bombardments along with small arms fire broke up several attacks during the day. Throughout the night the North Vietnamese continued their attempt to defeat the Americans, but intensive fire from two batteries at Landing Zone Falcon and aggressive fighting by the cavalry repulsed the charges.

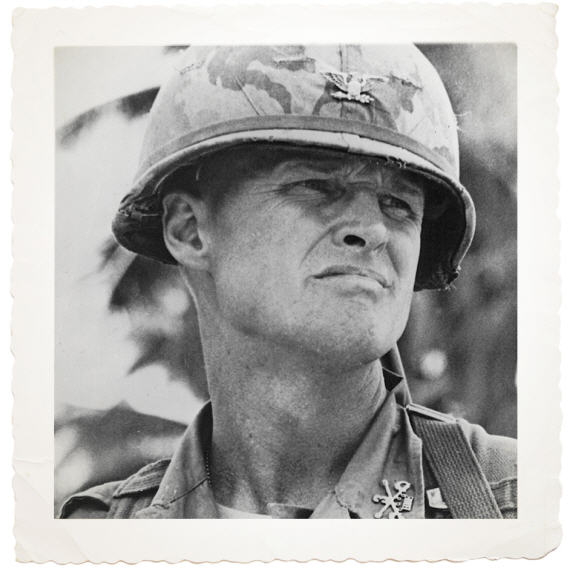

The battle at X-Ray carried on over the next two days. On the fifteenth the North Vietnamese repeatedly assaulted the Americans, Small arms fire became so intense that the forward observer from the most hard-pressed American company was pinned down and could not call in artillery fire. Fortunately, the artillery offcer located back at 1/7’s command post could see the fighting, adjusted artillery fire, and directed aerial artillery attacks and tactical air strikes. Despite effective air and artillery support, the enemy closed in on the perimeter and assailed it from all directions. Using colored smoke rounds to identify the precise outline of his perimeter, Lieutenant Colonel Harold G. Moore, the 1/7’s commander, called for additional artillery support. Heavily armed helicopter gunships entered the fray, while the two batteries at Landing Zone Falcon and two at Landing Zone Columbus laid down a devastating shield ot iron. This combination broke the enemy’s attacks for the day. The following day, the North Vietnamese renewed their assaults but ran into a curtain of artillery rounds. Using this as protection, the Americans then pushed towards the North Vietnamese, who retreated.

On the seventeenth the 2/7th Cavalry and the 2/5 Cavalry, which had joined Moore’s command on the fifteenth at X-Ray, moved on a sweep north to cut off North Vietnamese elements moving towards Columbus and Falcon. The 2/5 Cavalry arrived at Columbus without contacting the enemy, but the 2/7 Cavalry bumped into North Vietnamese at Landing Zone Albany. The engagement quickly deteriorated into a wild melee. Unable to distinguish between friend and foe, gun crews from Landing Zone Columbus and airmen waited patiently fir hours before they could respond. In mid-afternoon aerial and tube artillery and tactical air support joined the fight. Although the enemy applied pressure into the evening, a continuous ring of artillery shells and tactical air strikes kept it from breaching the perimeters. Unable to take such punishment, the N Vietnamese finally abandoned their drive to destroy the artillery that had been so destruc- tive at X-Ray. The North Vietnamese hit Columbus with mortar and machine gun fire on 18 November and battled the Americans at several other locations, but the fighting at Albany marked the last of major combat in the Ia Drang.

extraction LZ.

After the Battle of Ia Drang, General Kinnard had nothing but praise for his field artillery. “Using Chinooks, we had been able to position tube artillery in the midst of a literally trackless jungle where it provided close support to our infantry and gave them a vital measure of superiori- ty,” Kinnard wrote in Army in 1967.60 Besides lauding tube artillery, he boasted that aerial artillery had matured in the Ia Drang by supplementing tube artillery and in some cases providing the only firepower. Taking hi3 argument even further, Kinnard insisted that the 1st Cavalry lured the enemy into battle by teasing it with a “seemingly unprotected airmobile infantry battalion.” Once the enemy struck, the 1st Cavalry hit it hard with “massive artillery support.”60 Simply stat- ed, the battles of Ia Drang vindicated the airmobile concept and showed the field artillery’s capac- ity to provide close support in difficult terrain.

Lieutenant Colonel Lloyd J. Picou of the 1st Cavalry’s artillery responded with the same enthusiasm. Writing in Artillery Trends in August 1967, Picou explained that airmobile artillery proved its versatility and mobility, its ability to displace quickly, and its mastery of airmobile artillery techniques. 62 The following year, Picou explained in MilitaryReview, “From the division artillery viewpoint, the most significant outcome of this campaign [Ia Drang] was the use of aerial artillery.”63 Aerial artillery gunships flew to the scene and were able to locate and attack enemy forces. Pilots contacted ground units and then adjusted tube artillery on the fringes of the battle- field. As his article indicated, he believed that the field artillery had made a significant break- through with aerial artillery because it provided effective support to airmobile units.

The Army and 1st Cavalry Division drew two more conclusions. Both pointed out that operations in the Ia Drang revealed the importance of having mutually supporting field artillery positions.Towed 105-mm. howitzers could not be used in a direct fire role on a landing zone surrounded by dense vegeta- tion without causing extensive casualties to the security force. To protect one landing zone and its batter- ies, the field artillery had to site at least two batteries within range of each other. Because of guerrilla warfare, commanders simply could not position their field artillery without adequate protection.

In their efforts to justify airmobile operations, Kinnard and other officers overlooked an important weakness. During the short but intensive battles on 1and 3 November between small forces, tube artillery failed to furnish any support because it was out of range of the fights whereas aerial artillery rushed quickly forward to hit enemy units. Even though it was transported by heli- copter, tube artillery lacked sufficient mobility to respond to fast-moving situations. This meant that the infantry and cavalry would have to fight alone on the enemy’s terms unless they were under a protective umbrella of fire support. Likewise, firepower succeeded only because the North Vietnamese stood and fought. Although firepower was a decisive factor, it had limitations. Late in 1965, it could not be applied at will.

Because la Drang acquainted the enemy with American firepower and influenced it to avoid such encounters in the future, the Army had to inaugurate search-and-destroy operations in 1965-66 to ferret out the enemy.66 For example, covered by 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzer batteries posi- tioned in the mountains bordering the Bong Son River, assaults by the 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry, landed south of the river on 28 January 1966 to deceive the enemy, attacked northward over the river with the Vietnamese Airborne Brigade, and destroyed two enemy battalions. On 6 February as a battalion of Marines sealed off the north end of the An Loa Valley to prevent the enemy from escaping, the division’s 2nd Brigade air assaulted into An Lao Valley. As the 2nd Brigade opened a thrust south down the valley, the rest of the division pushed rapidly southwest of Bong Son.

This rapid sweep taxed the 1st Cavalry’s artillery’s ability to support the maneuver elements. Even though field artillery officers tried to minimize displacements, the speed of the ground troops and the size of the area compelled them to make over 160 displacements, which strained the division’s air resources. When the pieces were moved by helicopter, field artillerymen generally transported ammu- nition and guns separately. To economize and speed up displacements they devised a system of using one helicopter to carry both. They suspended the ammunition and the howitzer beneath the helicopter by means of a double-sling system to allow the transportation of a complete firing section. By doing this, field artillerymen reduced the time required to occupy a position and dispelled fears about the field artillery’s inability to keep up with the other combat arms on a highly mobile battlefield.

Even though 1st Cavalry field artillerymen could maneuver their 105-mm. howitzers around, they wanted still more firepower. Without suitable roads 155-mm. howitzers could not occupy positions within range of the objective. To resolve that shortcoming field artillerymen airlifted the howitzers. Using CH-54 Flying Cranes and CH-47 Chinook helicopters and reducing the weight of the 155-mm. howitzer by eliminating unnecessary equipment, the 1st Cavalry flew a four-gun battery a distance of fifteen miles in approximately two hours to provide fire for the ground forces. This movement set an important precedent as it indicated that medium guns could be air- lifted and therefore possess the same mobility as lighter pieces had.

during those early days of 1966, field artillerymen in the 1st Cavalry also developed new tactics for aerial artillery. While tube artillery was adjusted on a target, aerial artillery orbited as near as possible. If any enemy tried to escape, aerial gunners fired on them. Whenever possible or appropriate, the pilots adjusted tube artillery to flush personnel into the open and then attacked. The ability to airlift towed 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzers and the rapid response of aerial artillery signified important changes in tactics. The 1st Cavalry had the capability to maneuver their artillery aggressively on the battlefield to destroy the enemy and refused to allow difficult terrain to hinder delivering huge amounts of firepower upon enemy positions.

The war concurrently forced the field artillery to refine certain gunnery techniques. In past wars field artillerymen could predict the enemy’s moves because they were primarily confined to a sector and could be plotted on a map with some degree of accuracy. Vietnam changed this. Because of the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong practice of hitting from any direction at any time, gun crews had to respond quickly and deliver fire in a full circle.71 Realizing that existing procedures were inadequate, gun crews improvised their own to furnish fire in a complete circle. This created varying ways. To eliminate confusion The Artillery and Missile School devised a method to fire in a complete circle in 1966 and disseminated it throughout the Army.72 Moreover, the school increased its instruction time on firing in a complete circle (6400-mils) to prepare grad- uates better for combat in Vietnam.

As important as technique was, suitable field pieces facilitated firing in a complete circle. The M108, M109, and M102 howitzers had the capability of traversing 360 degrees with ease, offset the limited traverses of other field guns, such as the 8-inch howitzer and 175-mm. gun, and complemented the revised 6400-mil firing chart.

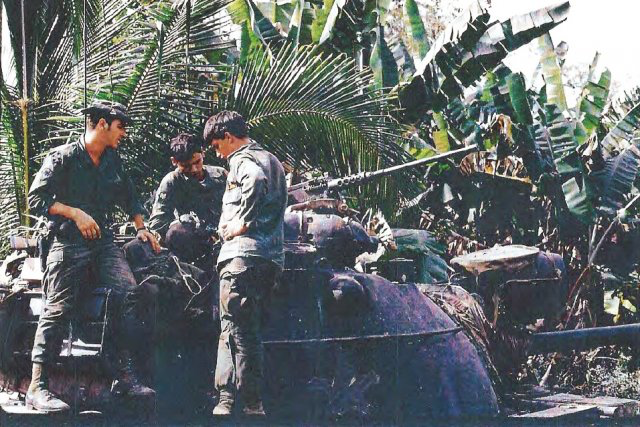

Although search-and-destroy operations of late 1965 and early 1966 were successful, the Army still had difficulties protecting the countryside. To ensure that the maximum area was defended by available troops, the Army assigned an area of operations to each unit from the high- est to the lowest. This dispersed the Army throughout the countryside. Because of the size of the brigade’s area and range limitation, the division artillery commander attached a battery to a partic- ular battalion to provide the maximum coverage. Consequently, an artillery battalion no longer supported an entire brigade as it had done in previous wars. This habitual association decentral- ized fire direction from the battalion to the battery and frequently isolated the battery from the rest of its battalion. Addressing this development, Brigadier General James G. Kalergis, Commander, I Field Force Vietnam Artillery, explained in 1967 that field artillery batteries normally performed as if they were battalions and that battalions acted as if they were division artillery or group head- quarters. This transferred the authority to make key decisions from the battalion commander or higher to the battery commander. For example, Operation Fitchburg of late 1966 and early 1967 in Tay Ninh Province gave the battery commander “an excellent opportunity to exercise com- mand and control independent of the artillery battalion” because one 105-mm. howitzer battery was placed in direct support of each maneuver element.

Commanders permitted batteries to operate independently because the war was basically a small unit conflict and was being fought over a large area. Although commanders preferred to keep fire direction under the battalion’s control, batteries had to be able to direct their own fire since they were often employed piecemeal into battle. In some cases, batteries fragmented operations even more by assigning part of their guns for base camp defense and the other for tactical employment.

Because of operations over vast areas, numerous displacements, short, violent actions, and an undefinable front and rear in 1965-66, the field artillery found the battery-battalion arrangement to be logical and to provide fast, accurate fire. As a result, the enemy feared American field artillery and made batteries prime targets for infiltration or full-scale attacks. Unable to perform their mis- sions and protect themselves simultaneously, field artillerymen created fire support bases by posi- tioning their pieces with the command post of a maneuver battalion. From these positions located so that any point in the area of operations could be reached by at least one battery and usually two or more, the maneuver commander conducted offensive operations, while field artillery, ranging from 105-mm. howitzers to 175-mm. guns, furnished fire support and helped defend other fire bases as required. This arrangement guaranteed a rapid response by the artillery when called upon, simplified furnishing fire support in guerrilla warfare, and saved lives. The base along with the availability of naval gunfire and tactical air gave the Army the capacity to rain deadly fire and reinforced the grow- ing trend of relying upon firepower rather than maneuver for defeating the enemy.

Most commanders concluded that the overriding lesson of 1965-66 was the importance of firepower. As the battles indicated, American ground forces were vulnerable when they lacked fire support. Because of that, many commanders reluctantly operated beyond their artillery or tac- tical air support and refused to fight on equal terms with the enemy. 78 Commenting on this, Brigadier General Willard Pearson, Commander, 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, wrote in December 1966 that his unit’s motto was “Save Lives, Not Ammunition.”79 Given this, he wrote December 1966 that the ground forces’ main task involved finding the enemy. Artillery and air power had the responsibility of defeating, routing, or destroying the enemy. In December 1966 he admitted, “Our airmobile operations and fire support then become the mainstay of our offensive.” 80 Along with other commanders, Pearson insisted that massive artillery and air fire were the most effective ways to crumble enemy resistance. Although some officers opposed such a tactic, most commanders valued firepower because it preserved lives. A memorandum for General Kalergis pointed out “There is not [a] price tag in [on] the life of a US soldier, massive use of artillery, air and naval support will save US lives….

The war in 1965-66, therefore, forced the field artillery to modify tactics and organization. Without a front line gun crews did not have the luxury of establishing positions in the rear areas, had to fire in a complete circle, had to defend themselves from infiltrators, had to airlift their pieces into remote areas, and had to decentralize their batteries through habitual association to provide support in many cases. Even though habitual association created fierce loyalties between the infantry and field artillery, it made massing battalion and division fire difficult and elevated the importance of the battery fire direction center. Despite these adaptations during the heat of combat, the field artillery gave prompt, reliable support. Along with the pressure from public opinion to preserve lives, by 1966 the Army made field artillery, naval, and air firepower more important than maneuver since infantry, armor, and cavalry units would not conduct operations unless they were under the protective umbrella of fire support.

Battles in 1967 and 1968 also reflected this preoccupation with firepower. Despite the success of the search-and-destroy operations in 1966, hostile bastions still dotted South Vietnam. Carefully situated in hard-to-reach areas–jungles, mountains, and swamps–and provided with escape routes, the bastions furnished the enemy excellent bases from which they assaulted South Vietnam.

Since the Iron Triangle was a formidable arrow tip pointing straight at Saigon, the Army decided late in 1966 to destroy that preserve even though previous attempts had failed. Early in January 1967, the 1st Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, the lth Armored Cavalry Regiment, and separate battalions of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam opened Operation Cedar Falls. The units moved into pre-arranged positions around the Triangle to seal it off and attacked.82 As expected, main force Viet Cong units dispersed as the Americans and South Vietnamese pushed into the bastion. Although enemy resistance was light, the field artillery fired missions from bases ringing the area of operations to seal off escape routes or reduce small points of resistance and fiercely shelled landing zones. Nevertheless, division artillery commanders had difficulty locating moving units and coordinating supporting fires. Because of this, the 1st Division’s artillery commander delegated fire control to commanders of direct support battalions, who helped convert the Iron Triangle from a haven into a no man’s land by the end of January.

Shortly thereafter, the Army launched another multi-division operation called Junction City. For years the insurgents had a major stronghold along the Cambodian border from which they had hit the South Vietnamese. Late in February, the Americans surrounded the area with eighteen bat- talions and thirteen mutually supporting fire bases and conducted search-and-destroy operations over the next three weeks.

Junction City culminated with the battles of Ap Bau Bang II, Suoi Tre, and Ap Gu. In each case Viet Cong forces attacked American fire bases with mortar rounds, rifle grenades, rockets, and recoilless rifle fire. To fight off the assaults the Americans employed small arms fire, field artillery, and air strikes. According to Brigadier General David E. Ott, Commander, 25th Division’s artillery, the most significant artillery action occurred around Fire Support Base Gold during the Battle of Suoi Tre. As infantry patrols swept around the base on 21 March, they bumped into a Viet Cong force that was preparing to assail the base. The accidental confrontation prematurely triggered a violent enemy attack. To defend themselves American gun crews levelled their tubes and spewed beehive rounds (canister rounds filled with hundreds of metal darts) into the Viet Cong. At point-blank range round after round hit the assaulting force as batteries from other bases threw up a continuous wall of shells around the perimeter and as air strikes pounded the attackers. This demonstration of firepower along with small arms fire compelled the Viet Cong to withdraw. 85

As Lieutenant General Bernard W. Rogers, who was the assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division in 1967, recalled in 1974, Cedar Falls/Junction City operations confirmed the importance of field artillery and air power. They verified the need to get as much firepower on the enemy as quickly as possible and to use artillery and air strikes simultaneously. Equally important, these operations reemphasized the value of 105-mm. howitzers because of their rapid-

fire capabilities and strengthened the requirement for mutually supporting bases.

In Summons of the Trumpet: US-Vietnam Perspective (1978), David R. Palmer, an advisor to the Vietnamese Military Academy and Vietnamese armor units during the Vietnam War, caught the essence of the transformation- of Army tactics caused by the drive for fire support. By 1967 only a foolhardy or a desperate commander would ever engage the enemy by any means other than firepower. Early drifts towards this mentality started in Ia Drang and culminated in 1967. Even though Army doctrine still called for fire and maneuver, practice in Vietnam differed con- siderably. Commanders located the enemy with infantry and then attacked with field artillery and air strikes. After leaving Vietnam General Westmoreland criticized this routine vigorously when he admitted that artillery and air power had produced a firebase psychosis.

In 1968 the North Vietnamese abandoned their strategy of a protracted war. Within twenty- four hours after the beginning of Tet, on 30 January 1968 Hanoi launched a series of attacks from the demilitarized zone to the southern tip of Vietnam. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese struck six major cities, sixty-four district capitals, and fifty hamlets and caught the Americans and South Vietnamese off guard. In Saigon the Antericans and South Vietnamese repulsed the initial assaults and cleared the city within several days. A similar pattern emerged in other places with the exception of Hue. After three weeks of heavy bombing and intensive artillery fire, the Americans and South Vietnamese finally liberated the city.

Generally, post-Tet operations reflected past counter-guerrilla operations. Enemy tactics compelled the resumption of small unit actions, ranging from squad- to company-size. As the other combat arms scoured the countryside, gun crews supplied close support by shelling enemy positions. As a means to extend offensive operations, the Army conducted artillery raids from fire bases into remote areas by displacing artillery to supplementary positions and quickly withdraw- ing. Normally, a raid included one 105-mm. howitzer battery, one understrength 155-mm. how- itzer battery (three howitzers), one rifle company for security, aerial observers from division artillery, and air cavalry for target acquisition and damage assessment when it was available. Equally important, American field artillerymen created a fourth firing battery in direct support battalions because of the clamor for more firepower and because of a surplus of guns and ammunition and increased the use of FADAC that had been introduced in Vietnam in 1966-67. In fact, FADAC had become the primary means of computing fire data by 1969.

Although FADAC did not eliminate the need for manual computation for backup capability, it greatly altered the field artillery’s performance in Vietnam. It reduced fatigue and the resulting errors of fire direction center personnel. By doing this FADAC greatly increased accuracy, decreased response time, and allowed gun crews to fire longer missions and hit more targets with less ammunition. For the field artillery these capabilities were critical because the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong were elusive, used hit-and-run tactics, and engaged the Americans and their allies at close distance with the idea of negating their superiority in artillery, helicopter, and tactical air support.

The war assumed a new dimension following Tet. Even though the North Vietnamese did not achieve their objective, their ability to initiate such an offensive stimulated a great debate in the United States. For many Americans the offensive symbolized the senseless destruction of the war. For the military Tet presented a golden opportunity to crush the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese because they were weakened by that great effort. Seeking to take advantage of the enemy’s condition, Westmoreland proposed a two-fisted offensive, a ground attack against sanctuaries in Laos and Cambodia and an intensive bombing campaign. In contrast, Pentagon civilians urged shifting from search-and destroy operations to population security by deploying the bulk of the military forces along the demographic frontier, a line just north of the major population centers. From here the military would defend against a major North Vietnamese thrust and engage in limited offensive operations to keep the enemy off balance. Pentagon civilians also wanted the South Vietnamese to assume more responsibility for their own defense and hoped to end the war through negotiation rather than a resounding military victory. Even though the military bitterly denounced this position and warned that it would produce certain disaster, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration accepted it in March 1968, an election year. Because of his opposition to expanding the war, President Johnson cut back bombing, informed the South Vietnamese that they had to shoulder more of the burden for defending themselves, and launched a peace initiative to create an independent, non-communist South Vietnam.

Although the Army continued fighting into 1973, Vietnamization changed the field artillery’s primary mission. beginning early in 1969, the Americans upgraded assistance pro- grams to improve South Vietnamese artillery operations, allowed the South Vietnamese to func- tion independently, and launched equipment modernization and training programs. Despite these efforts and those that strengthened the South Vietnamese army as a whole, South Vietnam final- ly collapsed in 1975 in the face of a determined North Vietnamese onslaught.

Even though the Vietnam War demonstrated the Army’s flexibility to move from its preoc- cupation with nuclear war to unconventional war, it also revealed the Army’s growing reliance upon firepower. Exploiting new field pieces coming off production lines and FADAC and dust- ing off forgotten techniques, field artillerymen delivered unprecedented accurate fire to shatter enemy attacks and seal off the battlefield and showed their ability to furnish huge quantities of fire. Ironically, the Army’s past conditioned soldiers to see firepower–artillery, naval guns, and tactical air-as the preferable solution.

Additionally, the Vietnam War highlighted the inherent shortcomings of consolidating the field and coast artillery. Following the closing of the Seacoast Artillery School in 1950 and dis- banding of coast artillery units or converting them to field or antiaircraft artillery that same year, only field and antiaircraft artillery (called air defense artillery after 1957) existed as part of the Army’s artillery. Because of the growing divergence of techniques, tactics, doctrine, equipment, and materiel for the two artilleries, the Continental Army Command outlined a plan in 1955 to develop basic courses in field artillery and antiaircraft artillery for new officers. Integrated basic and advanced officer courses, which had been initiated in 1947, had failed to provide officers with adequate preparation to serve effectively in either artillery.93 With support from the Army’s Assistant Chief of Staff for Training, the Continental Army Command created basic courses for the two artilleries in 1957 but reintegrated basic officer training in 1958 through 1961 because of the lack of officers and money.94 In the meantime, the Continental Army Command retained the integrated artillery advanced course for officers with five to eight years of experience because of pressure to maintain flexibility in officer assignments.

The pressure to end integrated training and form field artillery and air defense artillery as two distinct combat arms branches mounted. Based upon the report of the Army Officer Education and Review Board of 1958, the Continental Army Command reintroduced separate basic officer courses in 1962 because of the need for specialized training for new officers. Because the Army wanted flexibility to shift experienced artillery officers easily between field and air defense artillery units, the command retained the integrated advanced course. As a part of the advanced course, student officers received instruction at the Artillery and Guided Missile School and the Air Defense School at Fort Bliss, Texas. In a student thesis at the Army War College in 1963, Colonel William F. Brand pointed out that integrated training provided an inadequate amount of time for detailed instruction on all artillery weapons, which meant that officers left the advanced course without mastering any of the weapons. As a result, Colonel Brand urged separate training for field artillery and air defense artillery. At the direction of the Commanding General, Continental Army Command, the Artillery and Guided Missile School and the Air Defense School explored the desirability of dividing the artillery into two branches. In 1963 the schools recommended separation because of the difficulty of cross training and the growing difference between the two artilleries. In line with this, the authors of “The Artillery Branch Study” of 1966 wrote that integrated training “spawned mediocrity. ‘

In 1965-1967 the demand for field artillery officers with highly professional skills in the Vietnam War finally caused the Army and the Continental Army Command to reorganize the artillery. Because of the one-year tour that left little time for on the-job training, combat in Vietnam required the officer to arrive as a proficient field artilleryman and not a hybrid field and air defense artilleryman. Army commanders in Vietnam simply did not have the time to train an air defense artilleryman to be competent in field artillery and upgrade the skills of a field artillery- man, who had had insufficient training in the basic techniques. 97 Viewing the past years of inte- gration and its detrimental impact on field and air defense artillery and the need for qualified offi- cers in both artilleries, authors of “The Artillery Branch Study” urged ceasing the practice of cross training and forming two separate branches of artillery.

The Army concurred with the recommendations and split the field artillery and air defense artillery into two distinct combat arms with their own training programs in 1968. This freed field artillerymen to concentrate on field artillery subjects. Yet, separating the two artilleries had little impact upon the Artillery and Guided Missile School, which was renamed the Field Artillery School, because it was already focusing its energies on field artillery matters and not air defense artillery.

As such, the Vietnam War had a profound impact on the field artillery. After years of debate over the validity of consolidating field and air defense artillery, the war prompted the Army to recognize the existence of two artilleries and to make them independent of each other. Also, the war compelled the field artillery to adapt to fight a small-unit war, but it never abandoned its faith in massing fire.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers