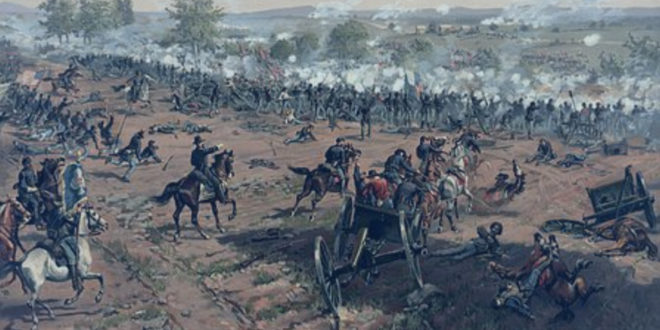

July 1, 1863. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania – The largest land battle ever fought in North America, involving about 90,000 Union and 75,000 Confederate troops, begins by accident when a column of southerners encounters Union cavalry while looking for a supply of shoes. On this first day the Confederates push the Union defenders out of the town but stop short of routing them off the field. Among the units engaged is the 2nd Mississippi Volunteer Infantry against elements of the famous j”Iron Brigade” (often referred to as the “black hats” due to the distinctive Hardee hats most of the men wore). The brigade was composed of the 2nd, 6th, 7th Wisconsin, 19th Indiana and 24th Michigan volunteer infantry regiments. In a sharp engagement in the woods near the McPherson’s Farm, nearly half of the 2nd Wisconsin are killed, wounded or captured. By nightfall the northerners take up key positions on a series of hills south of the town. The stage is set for what proved to be the climatic engagement of the war. The lineage of the Iron Brigade is carried today jointly by the 127th and 128th Infantry regiments, Wisconsin National Guard.

The Battle of Gettysburg was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war’s turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Meade’s Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, ending Lee’s attempt to invade the North.

After his success at Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, Lee led his army through the Shenandoah Valley to begin his second invasion of the North—the Gettysburg Campaign. With his army in high spirits, Lee intended to shift the focus of the summer campaign from war-ravaged northern Virginia and hoped to influence Northern politicians to give up their prosecution of the war by penetrating as far as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or even Philadelphia. Prodded by President Abraham Lincoln, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker moved his army in pursuit, but was relieved of command just three days before the battle and replaced by Meade.

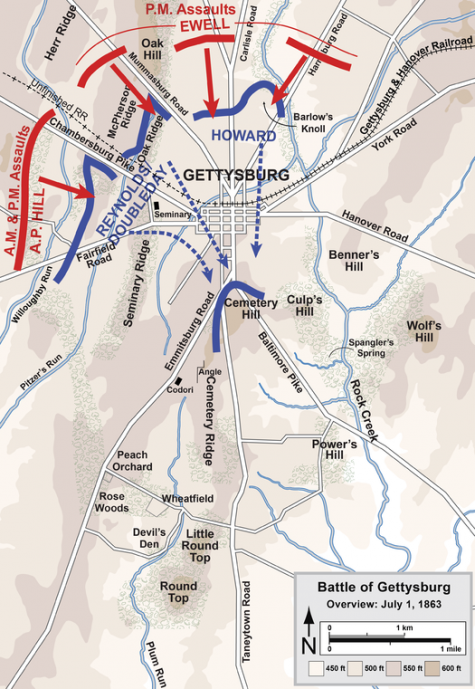

Elements of the two armies initially collided at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, as Lee urgently concentrated his forces there, his objective being to engage the Union army and destroy it. Low ridges to the northwest of town were defended initially by a Union cavalry division under Brig. Gen. John Buford, and soon reinforced with two corps of Union infantry. However, two large Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and north, collapsing the hastily developed Union lines, sending the defenders retreating through the streets of town to the hills just to the south.

On the second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flan k, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines.

k, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines.

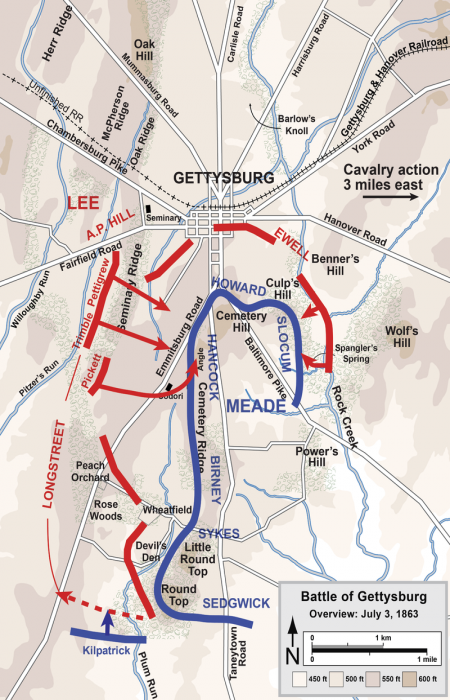

On the third day of battle, fighting resumed on Culp’s Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by 12,500 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, known as Pickett’s Charge. The charge was repulsed by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great loss to the Confederate army.

Lee led his army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the most costly in US history.

On November 19, President Abraham Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the fallen Union soldiers and redefine the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.

Military Situation

Shortly after the Army of Northern Virginia won a major victory over the Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30 – May 6, 1863), Robert E. Lee decided upon a second invasion of the North (the first was the unsuccessful Maryland Campaign of September 1862, which ended in the bloody Battle of Antietam). Such a move would upset U.S. plans for the summer campaigning season and possibly reduce the pressure on the besieged Confederate garrison at Vicksburg. The invasion would allow the Confederates to live off the bounty of the rich Northern farms while giving war-ravaged Virginia a much-needed rest. In addition, Lee’s 72,000-man army could threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and possibly strengthen the growing peace movement in the North.

Initial Movements to Battle

Thus, on June 3, Lee’s army began to shift northward from Fredericksburg, Virginia. Following the death of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, Lee reorganized his two large corps into three new corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet (First Corps), Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell (Second), and Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill (Third); both Ewell and Hill, who had formerly reported to Jackson as division commanders, were new to this level of responsibility. The Cavalry Division remained under the command of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart.

The Union Army of the Potomac, under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, consisted of seven infantry corps, a cavalry corps, and an Artillery Reserve, for a combined strength of more than 100,000 men.

The first major action of the campaign took place on June 9 between cavalry forces at Brandy Station, near Culpeper, Virginia. The 9,500 Confederate cavalrymen under Stuart were surprised by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s combined arms force of two cavalry divisions (8,000 troopers) and 3,000 infantry, but Stuart eventually repulsed the Union attack. The inconclusive battle, the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the war, proved for the first time that the Union horse soldier was equal to his Southern counterpart.

By mid-June, the Army of Northern Virginia was poised to cross the Potomac River and enter Maryland. After defeating the U.S. garrisons at Winchester and Martinsburg, Ewell’s Second Corps began crossing the river on June 15. Hill’s and Longstreet’s corps followed on June 24 and 25. Hooker’s army pursued, keeping between the U.S. capital and Lee’s army. The U.S. crossed the Potomac from June 25 to 27.

Lee gave strict orders for his army to minimize any negative impacts on the civilian population. Food, horses, and other supplies were generally not seized outright, although quartermasters reimbursing Northern farmers and merchants with Confederate money were not well received. Various towns, most notably York, Pennsylvania, were required to pay indemnities in lieu of supplies, under threat of destruction. During the invasion, the Confederates seized some 40 northern African Americans. A few of them were escaped fugitive slaves, but most were freemen; all were sent south into slavery under guard.

On June 26, elements of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division of Ewell’s Corps occupied the town of Gettysburg after chasing off newly raised Pennsylvania militia in a series of minor skirmishes. Early laid the borough under tribute but did not collect any significant supplies. Soldiers burned several railroad cars and a covered bridge, and destroyed nearby rails and telegraph lines. The following morning, Early departed for adjacent York County.

Meanwhile, in a controversial move, Lee allowed Jeb Stuart to take a portion of the army’s cavalry and ride around the east flank of the Union army. Lee’s orders gave Stuart much latitude, and both generals share the blame for the long absence of Stuart’s cavalry, as well as for the failure to assign a more active role to the cavalry left with the army. Stuart and his three best brigades were absent from the army during the crucial phase of the approach to Gettysburg and the first two days of battle. By June 29, Lee’s army was strung out in an arc from Chambersburg (28 miles (45 km) northwest of Gettysburg) to Carlisle (30 miles (48 km) north of Gettysburg) to near Harrisburg and Wrightsville on the Susquehanna River.

In a dispute over the use of the forces defending the Harpers Ferry garrison, Hooker offered his resignation, and Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck, who were looking for an excuse to get rid of him, immediately accepted. They replaced Hooker early on the morning of June 28 with Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, then commander of the V Corps.

On June 29, when Lee learned that the Army of the Potomac had crossed the Potomac River, he ordered a concentration of his forces around Cashtown, located at the eastern base of South Mountain and eight miles (13 km) west of Gettysburg. On June 30, while part of Hill’s Corps was in Cashtown, one of Hill’s brigades, North Carolinians under Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, ventured toward Gettysburg. In his memoirs, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, Pettigrew’s division commander, claimed that he sent Pettigrew to search for supplies in town—especially shoes.

When Pettigrew’s troops approached Gettysburg on June 30, they noticed Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford arriving south of town, and Pettigrew returned to Cashtown without engaging them. When Pettigrew told Hill and Heth what he had seen, neither general believed that there was a substantial U.S. force in or near the town, suspecting that it had been only Pennsylvania militia. Despite General Lee’s order to avoid a general engagement until his entire army was concentrated, Hill decided to mount a significant reconnaissance in force the following morning to determine the size and strength of the enemy force in his front. Around 5 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, two brigades of Heth’s division advanced to Gettysburg.

Opposing Forces

The Army of the Potomac, initially under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (Maj. Gen. George G. Meade replaced Hooker in command on June 28), consisted of more than 100,000 men in the following organization:

- I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth, Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson, and Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday.

- II Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. John C. Caldwell, John Gibbon, and Alexander Hays.

- III Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. David B. Birney and Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys.

- V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Sykes (George G. Meade until June 28), with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. James Barnes, Romeyn B. Ayres, and Samuel W. Crawford.

- VI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, Brig. Gen. Albion P. Howe, and Maj. Gen. John Newton.

- XI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, and Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz.

- XII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Alpheus S. Williams and John W. Geary.

- Cavalry Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, with divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. John Buford, David McM. Gregg, and H. Judson Kilpatrick.

- Artillery Reserve, commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert O. Tyler. (The preeminent artillery officer at Gettysburg was Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, chief of artillery on Meade’s staff.)

During the advance on Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. Reynolds was in operational command of the left, or advanced, wing of the Army, consisting of the I, III, and XI Corps. Note that many other Union units (not part of the Army of the Potomac) were actively involved in the Gettysburg Campaign, but not directly involved in the Battle of Gettysburg. These included portions of the Union IV Corps, the militia and state troops of the Department of the Susquehanna, and various garrisons, including that at Harpers Ferry.

In reaction to the death of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson after Chancellorsville, Lee reorganized his Army of Northern Virginia (75,000 men) from two infantry corps into three.

- First Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Lafayette McLaws, George E. Pickett, and John Bell Hood.

- Second Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Jubal A. Early, Edward “Allegheny” Johnson, and Robert E. Rodes.

- Third Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, with divisions commanded by Maj. Gens. Richard H. Anderson, Henry Heth, and W. Dorsey Pender.

- Cavalry division, commanded by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, with brigades commanded by Brig. Gens. Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, Beverly H. Robertson, Albert G. Jenkins, William E. “Grumble” Jones, and John D. Imboden, and Col. John R. Chambliss.

First Day of Battle (July 1, 1863)

Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge

Anticipating that the Confederates would march on Gettysburg from the west on the morning of July 1, Buford laid out his defenses on three ridges west of the town: Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge. These were appropriate terrain for a delaying action by his small cavalry division against superior Confederate infantry forces,  meant to buy time awaiting the arrival of Union infantrymen who could occupy the strong defensive positions south of town at Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp’s Hill. Buford understood that if the Confederates could gain control of these heights, Meade’s army would have difficulty dislodging them.

meant to buy time awaiting the arrival of Union infantrymen who could occupy the strong defensive positions south of town at Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp’s Hill. Buford understood that if the Confederates could gain control of these heights, Meade’s army would have difficulty dislodging them.

Heth’s division advanced with two brigades forward, commanded by Brig. Gens. James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis. They proceeded easterly in columns along the Chambersburg Pike. Three miles (5 km) west of town, about 7:30 a.m. on July 1, the two brigades met light resistance from vedettes of Union cavalry, and deployed into line. According to lore, the Union soldier to fire the first shot of the battle was Lt. Marcellus Jones. In 1886 Lt. Jones returned to Gettysburg to mark the spot where he fired the first shot with a monument. Eventually, Heth’s men reached dismounted troopers of Col. William Gamble’s cavalry brigade, who raised determined resistance and delaying tactics from behind fence posts with fire from their breechloading carbines. Still, by 10:20 a.m., the Confederates had pushed the Union cavalrymen east to McPherson Ridge, when the vanguard of the I Corps (Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds) finally arrived.

North of the pike, Davis gained a temporary success against Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’s brigade but was repulsed with heavy losses in an action around an unfinished railroad bed cut in the ridge. South of the pike, Archer’s brigade assaulted through Herbst (also known as McPherson’s) Woods. The U.S. Iron Brigade under Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith enjoyed initial success against Archer, capturing several hundred men, including Archer himself.

General Reynolds was shot and killed early in the fighting while directing troop and artillery placements just to the east of the woods. Shelby Foote wrote that the Union cause lost a man considered by many to be “the best general in the army.” Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday assumed command. Fighting in the Chambersburg Pike area lasted until about 12:30 p.m. It resumed around 2:30 p.m., when Heth’s entire division engaged, adding the brigades of Pettigrew and Col. John M. Brockenbrough.

As Pettigrew’s North Carolina Brigade came on line, they flanked the 19th Indiana and drove the Iron Brigade back. The 26th North Carolina (the largest regiment in the army with 839 men) lost heavily, leaving the first day’s fight with around 212 men. By the end of the three-day battle, they had about 152 men standing, the highest casualty percentage for one battle of any regiment, North or South. Slowly the Iron Brigade was pushed out of the woods toward Seminary Ridge. Hill added Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’s division to the assault, and the I Corps was driven back through the grounds of the Lutheran Seminary and Gettysburg streets.

As the fighting to the west proceeded, two divisions of Ewell’s Second Corps, marching west toward Cashtown in accordance with Lee’s order for the army to concentrate in that vicinity, turned south on the Carlisle and Harrisburg roads toward Gettysburg, while the Union XI Corps (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard) raced north on the Baltimore Pike and Taneytown Road. By early afternoon, the U.S. line ran in a semicircle west, north, and northeast of Gettysburg.

However, the U.S. did not have enough troops; Cutler, who was deployed north of the Chambersburg Pike, had his right flank in the air. The leftmost division of the XI Corps was unable to deploy in time to strengthen the line, so Doubleday was forced to throw in reserve brigades to salvage his line.

Around 2 p.m., the Confederate Second Corps divisions of Maj. Gens. Robert E. Rodes and Jubal Early assaulted and out-flanked the Union I and XI Corps positions north and northwest of town. The Confederate brigades of Col. Edward A. O’Neal and Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson suffered severe losses assaulting the I Corps division of Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson south of Oak Hill. Early’s division profited from a blunder by Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, when he advanced his XI Corps division to Blocher’s Knoll (directly north of town and now known as Barlow’s Knoll); this represented a salient in the corps line, susceptible to attack from multiple sides, and Early’s troops overran Barlow’s division, which constituted the right flank of the Union Army’s position. Barlow was wounded and captured in the attack.

As U.S. positions collapsed both north and west of town, Gen. Howard ordered a retreat to the high ground south of town at Cemetery Hill, where he had left the division of Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr in reserve. Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock assumed command of the battlefield, sent by Meade when he heard that Reynolds had been killed. Hancock, commander of the II Corps and Meade’s most trusted subordinate, was ordered to take command of the field and to determine whether Gettysburg was an appropriate place for a major battle. Hancock told Howard, “I think this the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw.” When Howard agreed, Hancock concluded the discussion: “Very well, sir, I select this as the battle-field.” Hancock’s determination had a morale-boosting effect on the retreating Union soldiers, but he played no direct tactical role on the first day.

General Lee understood the defensive potential to the Union if they held this high ground. He sent orders to Ewell that Cemetery Hill be taken “if practicable.” Ewell, who had previously served under Stonewall Jackson, a general well known for issuing peremptory orders, determined such an assault was not practicable and, thus, did not attempt it; this decision is considered by historians to be a great missed opportunity.

The first day at Gettysburg, more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third days, ranks as the 23rd biggest battle of the war by number of troops engaged. About one quarter of Meade’s army (22,000 men) and one third of Lee’s army (27,000) were engaged.

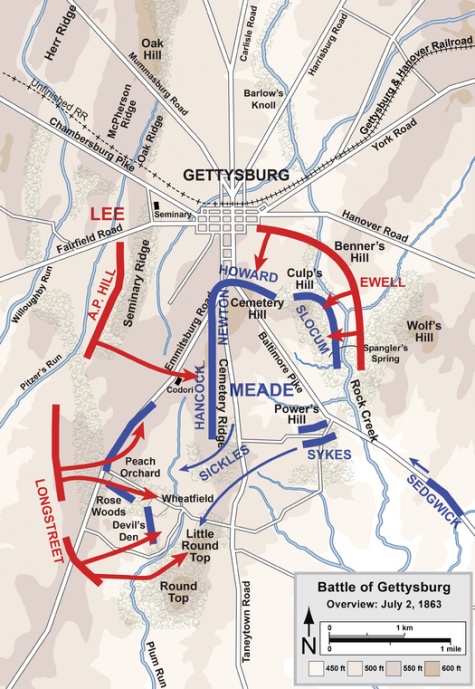

Second Day of Battle (July 2, 1863)

Little Round Top, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill

Plans and Movement to Battle

Plans and Movement to Battle

Throughout the evening of July 1 and morning of July 2, most of the remaining infantry of both armies arrived on the field, including the Union II, III, V, VI, and XII Corps. Longstreet’s third division, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Pickett, had begun the march from Chambersburg early in the morning; it did not arrive until late on July 2.

The Union line ran from Culp’s Hill southeast of the town, northwest to Cemetery Hill just south of town, then south for nearly two miles (3 km) along Cemetery Ridge, terminating just north of Little Round Top. Most of the XII Corps was on Culp’s Hill; the remnants of I and XI Corps defended Cemetery Hill; II Corps covered most of the northern half of Cemetery Ridge; and III Corps was ordered to take up a position to its flank. The shape of the Union line is popularly described as a “fishhook” formation. The Confederate line paralleled the Union line about a mile (1,600 m) to the west on Seminary Ridge, ran east through the town, then curved southeast to a point opposite Culp’s Hill. Thus, the Union army had interior lines, while the Confederate line was nearly five miles (8 km) long.

Lee’s battle plan for July 2 called for Longstreet’s First Corps to position itself stealthily to attack the Union left flank, facing northeast astraddle the Emmitsburg Road, and to roll up the U.S.line. The attack sequence was to begin with Maj. Gens. John Bell Hood’s and Lafayette McLaws’s divisions, followed by Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division of Hill’s Third Corps. The progressive en echelon sequence of this attack would prevent Meade from shifting troops from his center to bolster his left. At the same time, Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s and Jubal Early’s Second Corps divisions were to make a demonstration against Culp’s and Cemetery Hills (again, to prevent the shifting of U.S. troops), and to turn the demonstration into a full-scale attack if a favorable opportunity presented itself.

Lee’s plan, however, was based on faulty intelligence, exacerbated by Stuart’s continued absence from the battlefield. Instead of moving beyond the U.S. left and attacking their flank, Longstreet’s left division, under McLaws, would face Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’s III Corps directly in their path. Sickles had been dissatisfied with the position assigned him on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. Seeing higher ground more favorable to artillery positions a half mile (800 m) to the west, he advanced his corps—without orders—to the slightly higher ground along the Emmitsburg Road. The new line ran from Devil’s Den, northwest to the Sherfy farm’s Peach Orchard, then northeast along the Emmitsburg Road to south of the Codori farm. This created an untenable salient at the Peach Orchard; Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys’s division (in position along the Emmitsburg Road) and Maj. Gen. David B. Birney’s division (to the south) were subject to attacks from two sides and were spread out over a longer front than their small corps could defend effectively.

Attacks on the Union Right Flank

About 7:00 p.m., the Second Corps’ attack by Johnson’s division on Culp’s Hill got off to a late start. Most of the hill’s defenders, the Union XII Corps, had been sent to the left to defend against Longstreet’s attacks, and the only portion of the corps remaining on the hill was a brigade of New Yorkers under Brig. Gen. George S. Greene. Because of Greene’s insistence on constructing strong defensive works, and with reinforcements from the I and XI Corps, Greene’s men held off the Confederate attackers, although the Southerners did capture a portion of the abandoned U.S. works on the lower part of Culp’s Hill.

Just at dark, two of Jubal Early’s brigades attacked the Union XI Corps positions on East Cemetery Hill where Col. Andrew L. Harris of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, came under a withering attack, losing half his men; however, Early failed to support his brigades in their attack, and Ewell’s remaining division, that of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes, failed to aid Early’s attack by moving against Cemetery Hill from the west. The Union army’s interior lines enabled its commanders to shift troops quickly to critical areas, and with reinforcements from II Corps, the U.S. troops retained possession of East Cemetery Hill, and Early’s brigades were forced to withdraw.

Jeb Stuart and his three cavalry brigades arrived in Gettysburg around noon but had no role in the second day’s battle. Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s brigade fought a minor engagement with newly promoted 23-year-old Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer’s Michigan cavalry near Hunterstown to the northeast of Gettysburg.

Longstreet’s attack was to be made as early as practicable; however, Longstreet got permission from Lee to await the arrival of one of his brigades, and while marching to the assigned position, his men came within sight of a Union signal station on Little Round Top. Countermarching to avoid detection wasted much time, and Hood’s and McLaws’s divisions did not launch their attacks until just after 4 p.m. and 5 p.m., respectively.

Third Day of Battle (July 3, 1863)

Culp’s Hill, Pickett’s Charge and Cavalry Battles

Lee’s Plan

Lee’s Plan

General Lee wished to renew the attack on Friday, July 3, using the same basic plan as the previous day: Longstreet would attack the U.S. left, while Ewell attacked Culp’s Hill. However, before Longstreet was ready, Union XII Corps troops started a dawn artillery bombardment against the Confederates on Culp’s Hill in an effort to regain a portion of their lost works. The Confederates attacked, and the second fight for Culp’s Hill ended around 11 a.m. Harry Pfanz judged that, after some seven hours of bitter combat, “the Union line was intact and held more strongly than before.”

Lee was forced to change his plans. Longstreet would command Pickett’s Virginia division of his own First Corps, plus six brigades from Hill’s Corps, in an attack on the U.S. II Corps position at the right center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Prior to the attack, all the artillery the Confederacy could bring to bear on the U.S. positions would bombard and weaken the enemy’s line.

Largest Artillery Bombardment of the War

Around 1 p.m., from 150 to 170 Confederate guns began an artillery bombardment that was probably the largest of the war. In order to save valuable ammunition for the infantry attack that they knew would follow, the Army of the Potomac’s artillery, under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry Jackson Hunt, at first did not return the enemy’s fire. After waiting about 15 minutes, about 80 U.S. cannons added to the din. The Army of Northern Virginia was critically low on artillery ammunition, and the cannonade did not significantly affect the Union position.

Pickett’s Charge

Around 3 p.m., the cannon fire subsided, and 12,500 Southern soldiers stepped from the ridgeline and advanced the three-quarters of a mile (1,200 m) to Cemetery Ridge in what is known to history as “Pickett’s Charge”. As the Confederates approached, there was fierce flanking artillery fire from Union positions on Cemetery Hill and north of Little Round Top, and musket and canister fire from Hancock’s II Corps. In the Union center, the commander of artillery had held fire during the Confederate bombardment (in order to save it for the infantry assault, which Meade had correctly predicted the day before), leading Southern commanders to believe the Northern cannon batteries had been knocked out. However, they opened fire on the Confederate infantry during their approach with devastating results. Nearly one half of the attackers did not return to their own lines. Although the U.S. line wavered and broke temporarily at a jog called the “Angle” in a low stone fence, just north of a patch of vegetation called the Copse of Trees, reinforcements rushed into the breach, and the Confederate attack was repulsed. The farthest advance of Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead’s brigade of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division at the Angle is referred to as the “High-water mark of the Confederacy”, arguably representing the closest the South ever came to its goal of achieving independence from the Union via military victory. Union and Confederate soldiers locked in hand-to-hand combat, attacking with their rifles, bayonets, rocks and even their bare hands. Armistead ordered his Confederates to turn two captured cannons against Union troops, but discovered that there was no ammunition left, the last double canister shots having been used against the charging Confederates. Armistead was shortly after wounded three times.

There were two significant cavalry engagements on July 3. Stuart was sent to guard the Confederate left flank and was to be prepared to exploit any success the infantry might achieve on Cemetery Hill by flanking the U.S. right and hitting their trains and lines of communications. Three miles (5 km) east of Gettysburg, in what is now called “East Cavalry Field” (not shown on the accompanying map, but between the York and Hanover Roads), Stuart’s forces collided with U.S. cavalry: Brig. Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg’s division and Brig. Gen. Custer’s brigade. A lengthy mounted battle, including hand-to-hand sabre combat, ensued. Custer’s charge, leading the 1st Michigan Cavalry, blunted the attack by Wade Hampton’s brigade, blocking Stuart from achieving his objectives in the U.S. rear. Meanwhile, after hearing news of the day’s victory, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick launched a cavalry attack against the infantry positions of Longstreet’s Corps southwest of Big Round Top. Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth protested against the futility of such a move, but obeyed orders. Farnsworth was killed in the attack, and his brigade suffered significant losses.

Casualties

The two armies suffered between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties. Union casualties were 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured or missing), while Confederate casualties are more difficult to estimate. Many authors have referred to as many as 28,000 Confederate casualties, and Busey and Martin’s more recent 2005 work, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, documents 23,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing). Nearly a third of Lee’s general officers were killed, wounded, or captured. The casualties for both sides during the entire campaign were 57,225.

The following tables summarize casualties by corps for the Union and Confederate forces during the three-day battle.Confederate Casualties

| Confederate Corps | Killed | Wounded | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Corps | 1617 | 4205 | 1843 |

| Second Corps | 1301 | 3629 | 1756 |

| Third Corps | 1724 | 4683 | 2088 |

| Cavalry Corps | 66 | 174 | 140 |

Union Casualties

| Union Corps | Killed | Wounded | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|

| I Corps | 666 | 3231 | 2162 |

| II Corps | 797 | 3194 | 378 |

| III Corps | 593 | 3029 | 589 |

| V Corps | 365 | 1611 | 211 |

| VI Corps | 27 | 185 | 30 |

| XI Corps | 369 | 1924 | 1514 |

| XII Corps | 204 | 812 | 66 |

| Cavalry Corps | 91 | 354 | 407 |

| Artillery Reserve | 43 | 187 | 12 |

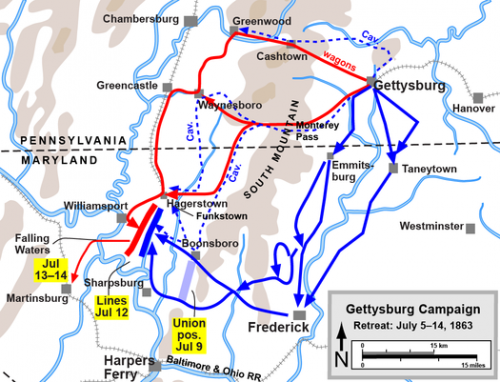

Confederate Retreat

The armies stared at one another in a heavy rain across the bloody fields on July 4, the same day that the Vicksburg garrison surrendered to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Lee had reformed his lines into a defensive position on Seminary Ridge the night of July 3, evacuating the town of Gettysburg. The Confederates remained on the battlefield, hoping that Meade would attack, but the cautious Union commander decided against the risk, a decision for which he would later be criticized. Both armies began to collect their remaining wounded and bury some of the dead. A proposal by Lee for a prisoner exchange was rejected by Meade.

Lee started his Army of Northern Virginia in motion late the evening of July 4 towards Fairfield and Chambersburg. Cavalry under Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden was entrusted to escort the miles-long wagon train of supplies and wounded men that Lee wanted to take back to Virginia with him, using the route through Cashtown and Hagerstown to Williamsport, Maryland. Meade’s army followed, although the pursuit was half-spirited. The recently rain-swollen Potomac trapped Lee’s army on the north bank of the river for a time, but when the Union troops finally caught up, the Confederates had forded the river. The rear-guard action at Falling Waters on July 14 added some more names to the long casualty lists, including General Pettigrew, who was mortally wounded.

In a brief letter to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck written on July 7, Lincoln remarked on the two major Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. He continued:

Now, if Gen. Meade can complete his work so gloriously prosecuted thus far, by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee’s army, the rebellion will be over.

Halleck then relayed the contents of Lincoln’s letter to Meade in a telegram. Despite repeated pleas from Lincoln and Halleck, which continued over the next week, Meade did not pursue Lee’s army aggressively enough to destroy it before it crossed back over the Potomac River to safety in the South. The campaign continued into Virginia with light engagements until July 23, in the minor Battle of Manassas Gap, after which Meade abandoned any attempts at pursuit and the two armies took up positions across from each other on the Rappahannock River.

The news of the Union victory electrified the North. A headline in The Philadelphia Inquirer proclaimed “VICTORY! WATERLOO ECLIPSED!” New York diarist George Templeton Strong wrote:

The results of this victory are priceless. … The charm of Robert E. Lee’s invincibility is broken. The Army of the Potomac has at last found a general that can handle it, and has stood nobly up to its terrible work in spite of its long disheartening list of hard-fought failures. … Copperheads are palsied and dumb for the moment at least. … Government is strengthened four-fold at home and abroad.

— George Templeton Strong, Diary, p. 330.

However, the Union enthusiasm soon dissipated as the public realized that Lee’s army had escaped destruction and the war would continue. Lincoln complained to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that “Our army held the war in the hollow of their hand and they would not close it!” Brig. Gen. Alexander S. Webb wrote to his father on July 17, stating that such Washington politicians as “Chase, Seward and others,” disgusted with Meade, “write to me that Lee really won that Battle!”

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers