On November 4, 1979, Iranian students seized the embassy and detained more than 50 Americans, ranging from the Chargé d’Affaires to the most junior members of the staff, as hostages. The Iranians held the American diplomats hostage for 444 days. While the courage of the American hostages in Tehran and of their families at home reflected the best tradition of the Department of State, the Iran hostage crisis undermined Carter’s conduct of foreign policy. The crisis dominated the headlines and news broadcasts and made the Administration look weak and ineffectual. Although patient diplomacy conducted by Deputy Secretary Warren Christopher eventually resolved the crisis, Carter’s foreign policy team often seemed weak and vacillating.

The Administration’s vitality was sapped, and the Soviet Uniontook advantage of America’s weakness to win strategic advantage for itself. In 1979, Soviet-supported Marxist rebels made strong gains in Ethiopia, Angola, and Mozambique. Vietnam fought a successful border war with China and took over Cambodia from the murderous Khmer Rouge. And, in late 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support its shaky Marxist government. DOD

A Classic Case of Deception

CIA Goes Hollywood

Forty years ago today, a crowd of college students broke into the housing complex at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran, and took 66 Americans hostage, including 26 service members.

Some of the hostages were released two weeks later, but the majority — 52 in all — were held for 444 days. They were released on Jan. 20, 1981….ToddLopez DOD

As part of U.S. efforts to free the hostages, eight U.S. service members were killed during a failed military operation called Operation Eagle Claw.

Background: Exfiltration and the CIA

When briefing the CIA’s Directorate of Operations (DO) or other components of the Intelligence Community (IC) about the Office of Technical Services’ (OTS) exfiltration capability, I always made a point to remind them that “readiness” is the key. This is one of the full-time concerns of my former OTS office, the Graphics and Authentication Division (GAD).

In arranging for the escape of refugees and other people of potential intelligence value who are subject to political persecution and hostile pursuit, prior planning is not always possible because they show up at odd hours in out-of-the-way places. Current surveys and collection of up-to-date intelligence regarding travel controls and procedures are vital. OTS engages in this activity worldwide.

The readiness to move clandestine agents out of harm’s way using quasi-legal methods is equally important. CIA’s policy and practice are to bring its valuable human assets in from the cold when they can no longer remain in place. Sometimes this includes their families. Public Law 110 gives the IC the authority to resettle these people in the United States as US persons when the time comes and the quota allows.

OTS/GAD and its successor components have serviced these kinds of operations since OSS days. The “authentication” of operations officers and their agents by providing them with personal documentation and disguise, cover legends and supporting data, “pocket litter,” and so forth is fundamental deception tradecraft in clandestine operations. Personal documentation and disguise specialists, graphic artists, and other graphics specialists spend hundreds of hours preparing the materials, tailoring the cover legends, and coordinating the plan.

Infiltrating and exfiltrating people into and out of hostile areas are the most perilous applications of this tradecraft. The mental attitude and demeanor of the subject is as important as the technical accuracy of the tradecraft items. Sometimes, technical operations officers actually lead the escapees through the checkpoints to ensure that their confidence does not falter at the crucial moment.

Operation in Iran: Going Public

The operational involvement of GAD officers in the exfiltration from Iran of six US State Department personnel on 28 January 1980 was a closely held secret until the CIA decided to reveal it as part of the Agency’s 50th anniversary celebrations in 1997.

David Martin, the CBS News correspondent covering national security issues in Washington, DC, had the story early on, as did Mike Ruane of The Philadelphia Inquirer. The Canadian Broadcasting Company and Reader’s Digest both have done serious pieces since the CIA opened the files on this important success story.

Jean Pelletier’s book, Canadian Caper, published in 1980, mentions that Canada–whose diplomats in Tehran had hidden and cared for the six American “houseguests” after Iranian militants seized the US Embassy–had received CIA help in the form of forged entries in Canadian passports to enable Canadian Ambassador to Iran Kenneth Taylor to engineer the escape of the six from Iran. A brief passage in Hamilton Jordan’s book, Crisis, alludes to CIA officers on the scene in Tehran. After he left office, former President Carter, in statements to the media, gave hints of even more credit due his administration for the only true operational success of the hostage crisis.

My recollections of the long national emergency–which began on 4 Nov-ember 1979 with the US Embassy takeover and ended with the release of the 52 hostages 1 on Inauguration Day in January 1981–encompass several major plans and operational actions focused on Iran that were supported by OTS. These included intelligence-gathering, deception options, the hostage rescue effort, secret negotiations with the Iranian Government; and exfiltrations of agents and the “Canadian six.”

In those days, the atmosphere in CIA was one of full alert. OTS, like many Agency components, was buzzing with intense activity. There are numerous stories about technical and operational innovations resulting from the emergency-like environment; the rescue of the six is one of many such stories.

New Job, New Challenge

On 11 December 1979, about a month after the takeover of our Embassy in Tehran, I moved from my job as Chief, OTS, Disguise Section, to Chief, OTS, Authentication Branch. I had operational responsibility worldwide for disguise, false documentation, and forensic monitoring of questioned documents for counterterrorism or counterintelligence purposes.

I had already spent the first days of the crisis creating a deception operation designed to defuse the crisis. President Carter decided not to use this plan, however. He has since lamented that decision.

The requirement for dealing with the six State Department employees hiding under the care of the Canadian Embassy in Iran was one of many challenges I had to address on my first day on the new job. I immediately formed a small team to work on this problem.

The complexities were evident. We needed to find a way to rescue six Americans with no intelligence background, and we would have to coordinate a sensitive plan of action with another US Government department and with senior policymakers in the US and Canadian administrations. The stakes were high. A failed exfiltration operation would receive immediate worldwide attention and would seriously embarrass the US, its President, and the CIA. It would probably make life even more difficult for all American hostages in Iran. The Canadians also had a lot to lose; the safety of their people in Iran and security of their Embassy there would be at risk.

But we had maintained a very impressive record of success with operations of this type over many years.

Collecting Basic Data

We had recently moved one agent out of Iran through Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport. As a result of this operation, we had a body of technical data on the airport controls and the competence and efficiency of the people operating them. The task of collecting and analyzing current document intelligence thus would be a matter of verifying fairly recent information and ensuring that it was up to date, rather than having to start from scratch.

We also were continuing to support the infiltration and exfiltration of a few intelligence officers and agents who were traveling in and out of Iran on intelligence-gathering and hostage-rescue planning operations. We could use these people as collection sources.

Major Potential Obstacles

We were most concerned about the exit controls at the airport. Long before the revolution, Iranian authorities had adopted a two-sheet embarkation/disembarkation form. This form was printed on carbonless paper and filled out by the traveler upon entry. The authorities retained a white sheet, and the traveler retained a yellow copy to present at the exit control point when departing. The clerk was supposed to match the two forms to verify that the traveler left before his visa expired. Many countries in the world have similar systems; few complete the verification process on the spot, if ever.

We hoped to determine whether the militants operating at Mehrabad were completing this kind of positive check before travelers cleared the airport. Earlier in 1979, the control personnel were unprofessional and did not collect the forms unless the departing traveler volunteered them. We had to determine whether this was still the case.

Another significant challenge we faced was to come up with a cover story and supporting documentation for a group of North American men and women. We debated three interconnected issues related to this aspect of our planning: the type and nationality of passports we should use, the kind of cover, and whether we should move the six out in a group or individually.

CIA management had strong opinions on these points, as did the State Department. And the Canadian Government would have to be drawn into the discussions at some point. Once it was, it too would also tend to take strong positions.

The Passport Question

The debate over passports began with the question of whether to use ordinary US passports, Canadian passports, or other foreign passports at our disposal. CIA managers were not comfortable with the idea of using foreign passports. They were concerned that persons who were not intelligence professionals could well prove unable to sustain a foreign cover story.

The Iranians, moreover, had embarrassed the US by finding a pair of OTS-produced foreign passports in the US Embassy that had been issued to two CIA officers posted in Tehran. One of these officers was among the hostages being held in the Embassy. The discovery of the passports was the topic of extensive media coverage in Iran and other countries.

Regarding Canadian passports, we initially doubted that Canada would be prepared to overlook its own passport laws. We also did not think Ottawa would be willing to put Canadian citizens and facilities in Iran in the increased danger they would face if the true purpose and American use of the passports were exposed.

Given these drawbacks and obstacles to the Canadian and other foreign passport options, it seemed that OTS would have to take on the task of building a cover for the use of US passports. But we feared that such an exercise would call unwanted attention to the six subjects and put them at greater risk.

On balance, our experience and judgment ultimately favored using Canadian passports, despite the risks. We decided to push for this option, but to concentrate first on devising cover for the six before making final recommendations on the type of passport to be used.

Quest for Information

We began an all-source quest for information on the types of groups traveling in and out of Mehrabad Airport. In the meantime, the DO’s Near East (NE) Division was developing information on overland “black” exfiltration options, hoping to identify a smuggler’s route or a “rat line” into Turkey. Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot had used such a plan to exfiltrate two of his employees early in the Iranian revolution. He had already offered support to the Agency for hostage rescue efforts.

We soon developed information which indicated that groups traveling legally to Iran included oilfield technicians from European-based companies, news teams of all nationalities covering the hostage situation, and all sorts of curiosity seekers and do-gooders from around the world. Many of these people were US citizens. None fit our purposes, given the profiles and patterns of these groups and the careful scrutiny and control applied to them by the Iranian security and immigration services. We believed it was important that professional intelligence officers make the final probe into Iran and meet personally with the six in order to assess their state of mind and their ability to carry out the operation.

Talks with the Canadians

We requested a meeting with senior NE managers to present our position and to review the options. We were also aware that the senior NE officer in charge of rescuing the six and conducting liaison with the Canadians on the crisis had already visited Ottawa, where his talks with officials in a Canadian government ministry had included the topic of Canadian passports. Our meeting with NE Division officers went fairly well, and they agreed in principle with our position.

Because the Canadians were understandably concerned with the mechanics of the exfiltration and how their passports would be used, we suggested that OTS get approval to go to Ottawa to explain these details. An OTS documents specialist, “Joe Missouri,” and I arranged to depart for Ottawa immediately. We prepared passport photos and appropriate alias bio data for the six, which we would take with us to Ottawa in the hope that we could win the Canadians over. We had already directed many questions to Canadian Ambassador Taylor, and his replies had given us a good feeling about his penchant for clandestine planning.

In our discussions with Canadian officials, we learned that the Parliament in Ottawa had already approved the use of Canadian passports for non-citizens for humanitarian purposes. We immediately requested six spares for the six houseguests to give us a redundant capability for the operation. We also asked for two additional passports for use by CIA “escorts.” The Canadians agreed to the spares, but they declined to give us two additional passports because Parliament had not approved the exception to their passport law to cover professional intelligence officers.

We had an opportunity while meeting with our Canadian ministry contact, “Lon DeGaldo,” to display a bit of magic. He thought one of the proposed aliases had a slightly Semitic sound–not a good idea in a Muslim country. We quickly picked another name, and I forged a signature in the appropriate handwriting on the margin of a fresh set of passport photos. This trick was mostly showmanship, but it helped to establish our credentials as experts.

Next, we discussed cover legends. We explained the different points of view on group cover versus individual cover, the need to gather more information on travelers, and our intention to send an officer or officers into Tehran to do a final probe of the controls and to meet with the six houseguests.

This gave me an opportunity to try out an idea for a cover legend that had occurred to me the night before at home in Maryland while I was packing. Cover legends hold up best when their details closely follow the actual experience or background of the user. If possible, the cover should be sufficiently dull so that it does not pique undue interest. In this case, however, I believed we should try to devise a cover so exotic that no one would imagine it was being used for operational purposes.

Hollywood Consultation

In my former job as chief of the OTS Disguise Section, I had engaged the services of many consultants in the entertainment industry. Our makeup consultant, “Jerome Calloway,” was a technical makeup expert who had received many awards. (He recently was awarded CIA’s Intelligence Medal of Merit, one of the few non-staffers to be so honored.) His motivation for helping us was purely patriotic.

We had already involved Jerome in the hostage crisis. One week after the takeover, I had invited him to Washington to help prepare a deception option related to the crisis. He, the disguise team, and I had worked around the clock to complete this option in five days.

When we received orders to stand down on that undertaking, Jerome returned to California. Before leaving, he reaffirmed his desire to help in any way possible in the rescue of our diplomats. As soon as I checked into my hotel in Ottawa, I called Jerome at his home. He had no idea what I was working on. I simply said that I was in Ottawa and that I needed to know how many people would be in an advance party scouting a site for a film production.

Jerome replied that this would require about eight people, including a production manager, a cameraman, an art director, a transportation manager, a script consultant, an associate producer, a business manager, and a director. Their purpose would be to look at a shooting site from artistic, logistic, and financial points of view.

The associate producer represented the financial backers. The business manager concerned himself mainly with banking arrangements; even a 10-day shoot could require millions of dollars spent on the local economy. The transportation manager rented a variety of vehicles, ranging from limousines to transport the stars to heavy equipment required for constructing a set. The production manager made it all come together. The other team members were technicians who created the film footage from the words in the script.

Because movie-making is widely known as an unusual business, most people would not be surprised that a Hollywood production company would travel around the world looking for the right street or hillside to shoot a particular scene.

Cover Options

Recommending this kind of cover for most clandestine activities would be out of the question, but I sensed that it might be just right for this operation. I tried the idea on Lon, our ministry contact, and he was intrigued with it. Certainly it was not incompatible with the Canadian passport option. Film companies are typically made up of an international cast of characters. The Canadian motion picture industry was well established.

We discussed the motion-picture cover option as well as another idea or two. Lon too had thought about the problem of cover; he had an idea for a group of food economists who might be seen traveling to various places in the Third World. The State Department had already given us a suggestion about a group of unemployed school teachers looking for jobs in international schools around the world. We felt obliged to mention this idea, even though we were not too excited about it.

We adjourned our meeting and made arrangements for follow-up talks. We then sent a cable to CIA Headquarters outlining our accomplishments, including our discussions on cover options. This was the first time that we reported the movie idea.

Over the next week (it was now late December), I commuted between Ottawa and Washington. An OTS team began forming in Ottawa to prepare the documentation and disguise items for a Canadian pouch to Tehran. The GAD team at OTS continued to collect information on Iranian border controls. All worldwide messages on the subject were being sent and answered with the Flash indicator, CIA’s highest precedence.

Senior CIA managers did not summarily reject the Hollywood option, recognizing that it could have advantages even beyond the problem of rescuing the six. The thinking was as follows:

The idea of using paramilitary means to rescue the hostages held at the US Embassy had seemed impossible, given Tehran’s geographical location. The movie cover might enable us to approach the Iranian Ministry of National Guidance with a proposal to shoot a movie sequence in or near Tehran. The Ministry had been charged with countering negative publicity on Iran by promoting tourism. Tehran was also looking for ways to alleviate some of the cash-flow problems caused when the United States froze Iran’s assets in the US. A motion picture production on Iranian soil could be an economic shot in the arm and would provide an ideal public relations tool to help counteract the adverse publicity stemming from the hostage situation.

A relative “moderate”–Abulhassan Bani-Sadr–was about to be elected President of Iran, and we judged it possible that he could be sold on these economic points and then might be able to gain agreement from the radical factions of the regime. If so, the cover for infiltrating the Delta Force (in preparation for a hostage rescue attempt at the Embassy) as a team of movie set construction workers and camera crews to prepare the set was a natural. We imagined that it might be possible to conceal weapons and other material in the motion picture equipment.

Forming a Film Company

One weekend in early January, between trips to Ottawa and planning sessions with NE Division, I made a quick visit to California. I brought along $10,000 in cash, the first of several black-bag deliveries of funds to set up our motion picture company. I arrived on Friday night and met with Jerome and one of his associates in a suite of production offices they had reserved for our purposes on the old Columbia Studio lot in Hollywood. I had invited a CIA contracts officer to the meeting to act as witness to the cash delivery and to follow up as bagman and auditor for the run of the operation. It would take two years to clear all accounts on these matters.

Our production company, “Studio Six Productions,” was created in four days, including a weekend, in mid-January. Our offices had previously been occupied by Michael Douglas, who had just completed producing The China Syndrome.

Jerome and his associate were masters at working the Hollywood system. They had begun applying “grease” and calling in favors even before I arrived. Simple things such as the installation of telephones were supposed to take weeks, but we had everything we needed down to the paper clips by the fourth day.

We arranged for full-page ads in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, the two trade papers most important to any business publicity campaign. We tried to keep Jerome’s well-known name hidden, but the “trades” had their reporters hot on our trail, and the word was out that something big was brewing in the industry.

When the press discovered that Jerome was connected with this independent production company, interest mounted and more press play followed. Our efforts to keep Jerome’s involvement secret actually added credibility to our putative film-making company. Hollywood, moreover, was an ideal place to create and dismantle a major cover entity overnight. The Mafia and many shady foreign investors were notorious for backing productions in Hollywood, where fortunes are frequently made and lost. It is also an ideal place to launder money.

Picking a Script

Once Studio Six Productions was set up, we tackled the problem of identifying an appropriate script. Jerome and I sat around his kitchen table discussing what the theme should be. Because Star Warshad made it big only recently, many science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero films were being produced. We decided we needed a script with “sci-fi,” Middle Eastern, and mythological elements. Something about the glory of Islam would be nice, too. Jerome recalled a recent script that might serve our purpose, and he hauled it out of a pile of manuscripts submitted for his consideration.

This script fit our purpose beautifully, particularly because no uninitiated person could decipher its complicated story line. The script was based on an award-winning sci-fi novel. The producers had also envisioned building a huge set that would later become a major theme park. They had hired a famous comic-strip artist to prepare concepts for the sets. This gave us some good “eyewash” to add to a production portfolio.

We decided to repackage our borrowed script by decorating it with the appropriate logo and title markings. The only copy of the script we needed would be carried by me as a prop to be shown to the Iranians in my role as production manager–and only in the event we were questioned at the airport in Tehran.

Argo

Jerome and I then set about picking a name for our movie. We needed something catchy from Eastern culture or mythology. After several tries, we hit on it! During our 10-year association, he had proven to be a great story and joke teller. He once told a group of us a profane “knock-knock” joke, with the word “Argo” in the punch line.

This word became an in-house disguise-team recognition signal and battle cry. We used it to break the tension that often built up when we were working long hours under difficult circumstances preparing for an important operation. Jerome remembered this. He also recalled that the name stemmed from mythology. He looked up the definition of Argo and confirmed it as the name of the ship on which Jason and the Argonauts sailed to rescue the Golden Fleece from the many-headed dragon holding it captive in the sacred garden. Perfect! This precisely described the situation in Iran.

I quickly designed an “Argo” logo, which we used for full-page ads in the trades. The ads proclaimed that “Studio Six Productions Presents ‘Argo’… A cosmic conflagration … story by Teresa Harris.” (Teresa Harris was the alias we selected for our story consultant; it would be used by one of the six awaiting our arrival in Tehran.)

Calling the Iranian Consulate

On my last day in California, I made our first business call from our studio offices to the Iranian Consulate in San Francisco, using my alias. I said I required a visa and instructions on procedures for obtaining permission to scout a shooting location in Tehran. My party of eight would be made up of six Canadians, a European, and a Latin American.

The Latin American would be an OTS authentication officer, “Julio,” who was posted in Europe. His languages were Spanish, French, and Arabic, and he had considerable exfiltration experience. We had selected OTS-produced documentation for his cover legend as an associate producer representing our production company’s ostensible South American backers. I would travel on an OTS-produced European passport.

The call to the Iranian Consulate was a washout. Officials there suggested that we apply at the nearest Iranian Consulate in our area. This was not surprising because many Iranian diplomats were carried over from the Shah’s regime, and most were unsure of their current status and their visa-granting authorities.

I departed on the “red-eye special” that night with all the trappings of a Hollywood type, including matchbooks from the Brown Derby Restaurant, where Studio Six Productions held a farewell dinner for me.

Final Technical Preparations

Back in Washington, the various efforts being mounted against Iran were still going full tilt. Our operations plan for the rescue of the six was being implemented at the working levels of OTS and NE Division, but it had not yet been coordinated with or approved by policymakers.

My immediate task was to participate in the final technical preparations for our three cover options. I had collected several exemplars of supporting documentation for our production party that were to be reproduced by the OTS graphics specialists to pad the wallets of our party. The script had to be altered and a presentation portfolio prepared for our production manager.

Joe Missouri, the document specialist who had accompanied me on the initial trip to Ottawa, had remained behind at that time to negotiate for ancillary documentation to support the Canadian part of the legend. This had required special authorization from senior levels of the Canadian Government, which Missouri managed to obtain. This was quite an accomplishment for a young officer.

By this time, Joe had returned to Washington and taken charge of the Argo portfolio. Joe had always been an artist at the typewriter. He took the roles of various members of the production party and fleshed them out in the form of resumes. This clever ploy provided briefing papers for each subject that could be carried in the open in the production manager’s portfolio. When completed, this portfolio had everything needed to sell even the most sophisticated investment banker on our movie.

A week after my return from California, the US and Canadian document and disguise packages were ready for the Canadian pouch. The OTS team in Ottawa had also been working on the Canadian documents, applying the finishing touches to the passports. We had 12 Canadian passports and 12 US passports, a redundant capability for both nationalities. The redundant documents were designed for final issuance by the Canadians in Tehran in case Julio or I failed to get in or did not show up at the Canadian Embassy after we arrived. Julio and I would complete the second set of passports in Tehran, giving us last-minute on-site flexibility.

A highly detailed set of instructions on the use of the documents and on the final briefing of the subjects had also been prepared for easy reference by non-experts. Airline tickets were enclosed showing around-the-world itineraries. Joe and I had found lapel pins and baggage stickers with a Canadian maple leaf design; these too were part of the kit.

A review of the US documents package on the night before we left for Ottawa to load the Canadian pouch revealed a possibly embarrassing problem. The Canadians were succeeding in getting backstopped Canadian documents. CIA’s ability to obtain similar backstopped alias documents was too slow, and we had not been able to obtain internal CIA permission to acquire these for our subjects. The US document packages were going to be terribly outclassed by the Canadians. In fact, the only reason for sending US alias documents was to appease one of the policymaking levels participating in the operations planning. The plan was still not finally approved or coordinated in our own government.

If our Canadian counterparts took inventory of the documents when we loaded the pouch, we would look silly. This bothered us. As soon as we arrived at the US Embassy in Ottawa the next morning, we made the rounds there collecting business cards and other wallet stuffers to fill out our package.

As it turned out, the loading of the “bag” did not include a close examination of our respective document packages, so we avoided embarrassment. The subjects themselves would have the final vote when presented with the choice of two passports, three cover stories, and the option of moving out individually or together. Because my OTS colleague and I ultimately would make the presentation of the choices in Tehran, we could greatly influence the decision.

The Canadian pouch or bag turned out to be the size of a pillowcase, barely big enough for our exfiltration kit of documents and disguise materials. The Canadian couriers apparently had a much easier time than the typical US State Department courier, who usually accompanies several mailbag-sized pouches. The Canadian courier is only allowed one bag, and he keeps it with him at all times. Some of our extra disguise materials had to be left out of the bag to Tehran.

During this last trip to Ottawa, it became clear that the Canadians were losing patience with the Americans. We still had not obtained our government’s final decision on our operations plan. They had made all sorts of concessions without hesitation. What was taking us so long to move? They insisted that final approval of all plans be accomplished as soon as possible. I promised to send that word back immediately.

Green Light

Back at the Embassy, I prepared a long cable outlining every detail of the operation as I envisioned it. This was precisely the kind of summary we would send in before launching an exfiltration from a foreign location. It was slightly irregular for me to send this from Ottawa as the plan that the Canadians and I wanted to be approved.

I caught hell for that cable when I returned to Washington, but then was told it was a fine piece of work. The plan received final approval within two days, and our materials were en route to Tehran.

Press Probes

A disturbing bit of information known to most of us involved in this operation had come to light weeks before. Certain members of the news media had figured out that the fuzzy information being provided to the press by our State Department spokesman in Washington regarding the exact number and identities of the hostages being held in the Embassy compound was a smokescreen designed to hide the fact that six diplomats were still at large in Tehran.

The Canadians were aware that the Washington correspondent of Montreal’s La Presse had already called on the Canadian Ambassador in Washington to voice his suspicions. The Ambassador asked him to sit on the information until after the exfiltration, promising him an exclusive on the story from the Canadian Government.

Ambassador Taylor’s wife, meanwhile, had received a cryptic phone call at their residence in Tehran. The caller did not identify himself, and he asked for one of the six by name. Two of the six were staying with the Taylors, and the call was for one of them, Joseph Stafford. The other four were staying in the residence of the Canadian Deputy Chief of Mission, John Sheardown. The Canadians saw their situation in Tehran becoming tenuous. They began making discreet arrangements to close down their Embassy before it too was overrun.

Moving to Europe

The next phase of the operation took place in Europe. The OTS shop there had been debriefing travelers, collecting data, and obtaining exemplars of the Iranian visas and entry cachets required for our up-to-date intelligence on Iranian document controls. Julio was gearing up his alias document package. My alias documentation was also being prepared there.

Julio and I planned to link up in Europe for our final launch into Tehran, tentatively set for 23 and 24 January. We intended to apply for Iranian visas separately in European cities. In case neither of us was successful, I had already arranged a fallback position. One of the CIA officers in Europe had an OTS-issued alias passport he used for operational meetings. Early in our data collection phase, we had instructed him to obtain an Iranian visa in this passport so we would have an exemplar. He got the visa. If necessary, I planned to borrow his alias and have a similar alias passport issued to me with a duplicate of his legally obtained visa.

Visa Applications

On Monday 21 January, Julio left for Geneva, Switzerland, on his alias passport to apply for an Iranian visa. I left Washington on the same day for Europe. I was traveling on my true-name US official documents, but I was hand-carrying the Studio Six portfolio and certain collateral materials to fill out our documents packages.

I arrived in Europe on the morning of 22 January, and Julio returned from his trip that afternoon with his Iranian visa. I still had to obtain a visa in my alias passport. I planned to drive to Bonn the next day and to apply there. I hoped the Iranians there would issue it in a few hours, as they had for Julio in Geneva.

We received a Flash message from Ottawa that afternoon. Our exfiltration kits had arrived in Tehran, but Ambassador Taylor and one of his aides had reviewed the materials and discovered a mistake! The handwritten Farsi fill-in on the Iranian visas showed a date of issue sometime in the future. The Farsi linguist assisting our team in Ottawa had misinterpreted the Farsi calendar.

We fired a message back through Ottawa assuring Taylor this was no problem. The OTS officers could easily alter the mistake when they arrived in Tehran. The fallacy in this was that the mistake was in the set of passports prepared for use by Taylor if we did not arrive for some reason. If this was the case, a follow-up message would be prepared with carefully worded instructions for Taylor on how to correct the mistake.

On Wednesday 23 January, one of the OTS officers and I went to Bonn. I had my alias documentation and the Studio Six portfolio. I had altered my appearance slightly with a simple disguise. I was also wearing a green turtleneck sweater, which I would continue to wear through the run of the operation.

As we approached the Iranian Embassy in Bonn, I noted that the Embassy of my ostensible country of origin was nearby. If the Iranians chose to do so, it would be perfectly proper for them to send me to my own Embassy for a letter of introduction before the visa was granted. I was dropped off down the block from the Iranian Embassy, and I walked back to the entrance to the consular section.

A half-dozen visa applicants were sitting in the reception area filling out applications. A handful of young Iranian “Revolutionary Guards” in civilian clothes were standing around scrutinizing everyone. It was then that I realized I had left the portfolio in the car when I was dropped off, but I had my alias passport and other personal identity documents. I filled out the forms and went to the clerk’s window to give them to the consular official.

In response to the official’s polite questions, I said, in my best accent, that the purpose of my visit to Tehran was to meet with business associates at the Sheraton Hotel in Tehran; they were flying in from Hong Kong today and were expecting me. I also said that I did not obtain a visa in my own country because I was in Germany on business when I received the telex about the meeting in Tehran. I received my visa in about 15 minutes.

Presidential OK

Our plan for entry into Iran was for me to leave that evening (23 January), and to arrive at Mehrabad Airport the next day at 5 a.m. Julio would follow the same itinerary 24 hours later. If anything happened to one of us en route, the other might still get through.

As soon as I got back from Bonn, I sent a Flash message to Washington and Ottawa that I was ready. I received approval to launch within the hour. Thirty minutes later, however, I received another message from Washington directing me to delay my departure because the President wanted to give final approval and was being briefed at that moment.

After 30 minutes, I received the presidential OK in a terse message which said, “President has just approved the Finding. You may proceed on your mission to Tehran. Good luck.” In terms of approvals, this case was the ultimate cliffhanger.

Entering Tehran

Julio and I had an especially worthwhile chance meeting just before I left for the airport that evening. We had an opportunity to meet with another Agency officer who had been traveling in and out of Tehran in support of the hostage rescue operation. He would ultimately be responsible for creating the inside support mechanism. He had been in the “business” since serving with OSS and parachuting into Europe during World War II. He clearly was a master of the game, and gave us some useful insights about the situation at Mehrabad and in Tehran. This strengthened our confidence and gave us a better idea about how to behave.

Julio and I both arrived in Mehrabad at 5 a.m. on Friday 25 January. (I was a day late because of delays caused by bad weather.) Immigration controls were straightforward, and the disembarkation/embarkation form was still being used. The difference I noted this time from my previous experience with Mehrabad immigration authorities was that the officer was a professional in uniform instead of an untrained civilian irregular. The immigration officers had gone into hiding at the beginning of the revolution. It appeared that they had now come back to work.

At entry, unlike my last visit, customs and security personnel were not overly concerned about foreigners. Because of Iran’s balance-of-payment problems, they were especially interested in Iranian citizens leaving with valuables like fine Persian rugs or gold. The economic situation had become worse in the last few months, and we could expect the exit controls to be tighter.

We took a taxi to the Sheraton Hotel and checked in. Our next step was to go to the Swissair office downtown to reconfirm eight airline reservations for Monday morning to Zurich. In an exfiltration operation, it is important to reconfirm your space on the airplane for the day you are supposed to leave. Because it is difficult to bring the subjects to the point where they have the courage to walk into the airport, if they then have to backtrack because their flight did not arrive or had mechanical problems, or their reservations were lost, it would be doubly hard for them to get up their nerve next time. We chose Swissair because of its record of efficient and reliable service.

The Swissair office was not open yet. From my earlier trip to Tehran, I knew that the US Embassy was a few blocks down the street and that the Canadian Embassy also was supposed to be nearby.

It seemed eerie approaching the US Embassy compound knowing that more than 50 Americans were being held inside, including CIA officers. The high walls were decorated with propaganda banners and posters celebrating the revolution. Although we knew our colleagues would experience some rough going during their captivity, we also knew there was nothing we could do to help at the time. We had to keep our attention on the task at hand.

Canadian Embassy

Julio and I began looking for the Canadian Embassy. Although our map showed it to be located directly across a narrow side street from the US Embassy, the building we found was the Swedish Embassy.

There was an Iranian guard at the entrance who did not understand our questions and was perplexed by our street map. Just then, a young Iranian came along. He spoke to the guard, apparently asking him who were these confused-looking Westerners. He then spoke to Julio in German. The fellow was polite and helpful. He wrote down an address in Farsi, hailed a taxi for us, and gave the address to the taxi driver, who took us a considerable way across town to the Canadian Embassy.

Ambassador Taylor, who had been expecting us to arrive sometime that morning, was waiting upstairs in his outer office. We did not immediately recognize him as the Ambassador. He was a tall, lean, rather young, pleasant individual dressed in Western jeans and a plaid shirt and wearing cowboy boots. He wore “mod” glasses and had a full salt-and-pepper Afro-style haircut. This improbable-looking diplomat greeted us warmly.

Ken introduced us to his secretary, Laverna, a small, elderly lady who was pleasant and cheerful. During a short meeting in Ken’s office, he explained that most members of his staff already had quietly departed Tehran. There would be only five Canadians left after his family departed that afternoon. The remaining five, including himself, would depart on Monday 28 January for London shortly after the Swissair flight we hoped to board at 7:30 a.m. with the houseguests. Early on Monday, he planned to inform the Foreign Ministry by diplomatic letter that the Canadian Embassy would be closed temporarily.

We described briefly the things we needed to accomplish over the next few days, starting with a meeting with the houseguests so we could brief them on the plan and assess their ability to carry it off. We all agreed the meeting would occur at 5 p.m. at the suburban residence of John Sheardown, the Embassy’s second officer, where four of the six houseguests had been hiding since November.

At this initial meeting with Ken, we learned that at least two more ambassadors in the local diplomatic corps and some of their staff also were involved in hiding and caring for the six. Ken and these other ambassadors were also visiting regularly with Bruce Laingen, the American chargé, who was under “house protection” in the Foreign Ministry. Laingen, another Embassy staff officer, and the Embassy security officer were to spend the entire crisis living in the rooms of the Foreign Ministry, where they had gone to protest the demonstrations at the gates of the US Embassy just as it was about to be overrun. Laingen was free to depart Iran any time, but he refused to abandon his colleagues.

We asked and received Ken’s permission to send a message to Washington through Ottawa, confirming our arrival in Iran and informing everyone concerned that we planned to meet with the six that evening. We were also introduced to Roger Lucy, who was house-sitting with the four Americans staying at Sheardown’s house. Roger spoke Farsi fluently; it was he who discovered our mistake on the visas.

Claude Gauthier was another member of Ken’s staff. He was a burly French Canadian responsible for the Embassy’s physical security. Claude earned the nickname of “Sledge” during these final days because he was destroying classified communications equipment with a 12-pound sledgehammer. Everyone at the Embassy was friendly and informal; they seemed amused by our business.

When it was time to go to meet the six, Julio and I left with Claude. Ken had left earlier to see his wife off at Mehrabad and to pick up the Staffords, the two houseguests who were staying with him. We all arrived at the Sheardown house at about the same time. The house was on the outskirts of town in a well-to-do neighborhood. It was palatial, with a high wall surrounding it.

Meeting the Six

The six houseguests rushed to meet us as we entered the house. They appeared in good spirits and were happy to see us. We spent the first few minutes getting acquainted. The six were two young married couples, Joseph and Kathleen Stafford and Mark and Cora Lijek, and two single men, Bob Anders and Lee Schatz. Anders, about 50, had been head of the consular section, and the two couples had worked for him. Schatz was a tall young man who was the agriculture attaché. Those from the Consulate had escaped out the back door to the street when the militants had been breaking in the front door. Schatz had had an office in a building across the street from the Embassy, and he had gone directly to the Swedish Embassy, where he hid for a week. The Swedish flag was his blanket.

I told them about the three cover stories that we were offering for their consideration. I also explained what had to be accomplished during the next two days and how we would proceed through the airport on Monday. There was considerable discussion about the mechanics of the controls and how we would respond if questioned about our presence in Tehran. Only one exhibited anxiety about the risks involved.

Finally, I instructed the six to go into the dining room to discuss among themselves whether they wanted to go to the airport in a group or individually and which cover story they preferred. I waited about 15 minutes and then walked in on them. They were debating the questions, and I distracted them by doing a bit of sleight-of-hand with two sugar cubes. I had used this trick many times to illustrate how to set up a deception operation and to overcome apparent obstacles. It helped to persuade reluctant subjects that they were involved with professionals in the art of deception. The six decided to go as a group, using the Studio Six cover.

The six showed us around the house, where four of them had passed nearly three months in a fair amount of comfort. The huge, well-furnished house had a kitchen with enough equipment for a modern restaurant. The Americans had spent a good bit of their time planning and cooking gourmet dinners for themselves and the few outsiders they saw. They also had become masters at the game of Scrabble.

As we were being shown around, one of the other ambassadors and his attaché, Richard, arrived. They had visited the houseguests more than once. They wanted to meet the CIA officers who had come to oversee the escape of the six people they had come to know well. Both these men were to prove helpful to us.

When it was time for Julio and me to go back to our hotel, Claude dropped us down the block from the hotel. He would pick us up the next morning to take us to the Canadian Embassy. On Saturday, we had to put the finishing touches on the Canadian passports and send our final plan of action to Ottawa and Washington for approval.

The Last Arrangements

The next two days passed swiftly. We spent most of Saturday filling in the passports with the appropriate entries, including the Iranian visas issued in Canada. The visa exemplar had been collected only recently for us by a Canadian friend in Ottawa. It was a better fit for the ostensible travel itinerary of the Studio Six team. Their cover legend and airline tickets showed them arriving in Tehran from Hong Kong at approximately the same hour that Julio and I had arrived from Zurich. Their flight had actually arrived on that day and time, and passengers disembarking would have been processed by the same immigration officers who had processed us. Consequently, the Iranian entry cachets stamped in our passports served as prime exemplars for those we entered in the passports of the six.

The worst thing that can happen when making false passport entries is to forge the signature of an immigration officer on an ostensible arrival cachet and then discover that this same individual is about to stamp you out of the country. He would know that he was not at work the day your passport says you arrived. You have to know how all these systems work.

The attaché, Richard, was dispatched to the airport to pick up a stack of the disembarkation/embarkation forms from an airline contact. Julio would complete the Farsi notations on enough of these, and each of the six would write in his or her false biographic information and sign in the new aliases. Again, the forms we had received and filled in on arrival were our models.

We spread out our forgery materials on a table in Ken Taylor’s office. He spent most of his day making last-minute arrangements to close the Embassy, sitting nearby and listening to our banter about some fine point of making false documents, or consulting with us on some detail of the arrangements for the exfiltration. Claude was wielding his sledgehammer somewhere in the building and burning and shredding classified paper.

On Sunday morning, I completed a long cable outlining the operations plan, and the message was transmitted to Ottawa. One of the details in the plan explained that:

. . . the six Canadians from Studio Six had called on the local Canadian Ambassador hoping that they could arrange for an appointment with the Ministry of National Guidance to present their proposal to use the local market for 10 days of shooting “Argo”. . . The Canadian Ambasssador has advised them to seek a location elsewhere if possible, but has offered one of the Embassy’s vacant residences as guest quarters . . . They heeded his advice, and after looking around a few days, have decided to leave Iran . . .

This provided details that paralleled the true facts. It also gave us the option of bringing the six to the airport on Monday in an Embassy vehicle with an Embassy driver, thereby solving the problem of finding reliable transportation to the airport. Laverna then could also reconfirm the airline reservations, which would be a normal service performed for Canadian guests of the Embassy.

Amateur Actors

Everything was in good order by Sunday night 27 January, when we reconvened at the Sheardown house. The six houseguests were impressed with their documentation packages, and we were impressed with the transformation of their appearances and personalities. On Friday night, we had given each of them their cover legend as prepared by Joe Missouri in the Studio Six portfolio. We also had provided them with disguise materials and props that would help fill out their roles.

They had scrounged clothes from one another and restyled their images to look more “Hollywood.” Each of them was having great fun playing their part and hamming it up. The most dramatic change was made by the rather distinguished and conservative Bob Anders. Now, his snow-white hair was a “mod” blow dry. He was wearing tight trousers with no pockets and a blue silk shirt unbuttoned down the front with his chest hair cradling a gold chain and medallion. With his topcoat resting across his shoulders like a cape, he strolled around the room with the flair of a Hollywood dandy.

The mental attitudes of the six were positive. We began briefing them on the details of their ostensible prior travel and arrival in Iran. They soon seemed to have grasped these details fairly well. We warned them that there was to be a hostile interrogation staged after dinner to test their ability to answer the questions under stress. Roger Lucy volunteered to be the interrogator.

Ken Taylor soon arrived with an answer from Ottawa to our cable. Apparently, the policymakers in Ottawa and Washington were pleased with our proposed plan of action. He said the last line of their cable was, “See you later, exfiltrator.”

Shortly, two senior friendly-country ambassadors arrived–the same two who were mentioned above as having been actively involved in efforts to hide and help the six Americans. The six served a sumptuous seven-course dinner with fine wine, champagne, coffee, and liqueurs. I told them about Jerome and the Argo knock-knock joke. Everyone took up the Argo cry. I also told everyone that they would be tempted to sell the story to some publisher after the operation was over. I admonished them not to yield to temptation, because Julio and I needed to stay in business to help others in the future. They apparently took this advice seriously.

After dinner, Roger appeared in military fatigues, complete with hat, sunglasses, jackboots, and swagger stick. The interrogations began. The interrogations impressed some of the more overconfident members of the group with the importance of remembering the details of their cover stories and gave them a taste of what could be in store for them at the airport.

During the interrogations, one of the ambassadors asked me to step into another room. He told me that, during one of the visits the three ambassadors had made to the Foreign Ministry to meet with Bruce Laingen and his aides, the US Embassy security officer had pulled him aside to confide that he was planning his own escape. He had already made one trip outside the building, and he asked for a glass cutter. The ambassador asked my advice about the glass cutter and if he should also give him a gun. I said “yes” to the glass cutter but “no” to the gun. I thanked him for this information, and told him we would be back in touch on these topics if more information was required.

Before we left at midnight, we made final arrangements for getting to the airport. I would go 30 minutes ahead of the others with Richard, who would pick me up at the hotel at 3 a.m. We would confirm that all was normal at the airport and that Swissair was en route from Zurich. I would clear customs and check in at the airline counter, where I would wait so the others could see me as they entered the airport as a signal that all was in order. Julio would accompany them to the airport in the Embassy van and lead the way through customs.

Day of Departure

I was awakened in my dark hotel room the next morning by the telephone ringing next to my bed. It was Richard calling from the lobby. It was 3 a.m., and I should have been up at 2:15. My watch alarm had gone off, and I must have slept through it. I rushed to shower and dress, arriving in the lobby about 15 minutes later.

Mehrabad is like many Middle Eastern or South Asian airports. Although of fairly modern construction, the people who pass through as travelers or hang around to greet or see travelers off make an orderly transit impossible. This was another reason for choosing the 7:30 a.m. Swissair flight. If we arrived at the airport at 5 a.m., the chances were the airport would be less chaotic. Also, the officials manning the controls might still be sleepy, and most of the Revolutionary Guards would still be in their beds. This was the case that Monday morning, 28 January 1980.

As Smooth as Silk

Richard and I proceeded through the customs check to the Swissair counter. There were few other travelers, and the airport employees were still groggy. The Swissair clerk confirmed that the flight would arrive at 5 a.m. I stood at my prearranged spot to wait for the rest of our party. Richard went to find the manager of another airline, who was a useful friend to have at the airport. He had already provided the blank embarkation forms. We would have had to collect these ourselves on the way in and had, in fact, picked up several extras, but the manager had given us plenty to cover any mistakes when filling them out. It is rare to have an inside contact at an airport for an exfiltration.

Soon the others arrived, and Julio led the way through customs. The six had had difficulty putting together a decent collection of luggage and clothing. They appeared to be traveling a bit light for Hollywood types on an around-the-world trip. They seemed bright and eager, however, and they had plastered their luggage with the Canadian maple leaf stickers we had found in Ottawa.

After they had cleared customs and checked in at the airline counter, we all proceeded to the immigration/emigration checkpoint. Lee Schatz was so eager that he had gotten way ahead of us and was already clearing the checkpoint, with no apparent difficulty. The others began presenting their documents and the yellow embarkation forms. I waited for each to clear in case one got into trouble. I would get involved quickly as the production manager responsible for the well-being of his pre-production crew. I was armed with the Argo portfolio and would overwhelm anyone standing in the way with Hollywood talk. The Iranian official at the checkpoint could not have cared less. He stamped each of us out and collected the yellow forms. One yellow form floated off his counter and was some distance away on the floor. When no one was looking, I picked it up and stuck it among my papers. It was the form we had forged for Bob Anders.

We were in the departure lounge, and we still had to go through the final security check before we arrived at the waiting area by our gate. The six were wandering around in the gift shops like ordinary tourists. A few fatigues-clad Revolutionary Guards were scrutinizing everyone.

Richard appeared with the airline manager. They had been watching us clear the checkpoint. I shook hands with the manager, and he asked me why we had not booked his airline; he would have arranged for red-carpet treatment. I told him to stand by because we might still need his flight if Swissair had any problem. I noticed the two elderly ladies from the Canadian Embassy starting to arrive in the departure lounge for their flight. Ken Taylor and the men of the Embassy would leave later in the day after we had departed.

Last-Minute Delay

The Swissair flight was called for the first time, and we proceeded through the security check into the small glassed-in room by our gate. We were just a short bus ride from the aircraft. Then the PA system announced that the Swissair flight was delayed for departure because of mechanical problems! I reassured our party and walked back through the security checkpoint to find Richard and his friend.

The departure lounge was filling up. Several flights were arriving. I wondered whether I should switch to one of these if Swissair was to be delayed too long.

I found Richard and his friend. They had already spoken to Swissair and learned the mechanical problem was minor. We would not be delayed too long, perhaps an hour. We discussed the options of switching flights, but we decided that that would be too complicated and that it would call unnecessary attention to us. I returned to our gate and reported this to the others.

We were all a bit on edge. The roving guards continued their random interrogations of other travelers. We made small talk and tried not to attract any attention.

After a tense hour, the Swissair flight was called. Everyone was suddenly anxious and excited about the prospect of pulling it off.

Success

The bus trip was brief and as we started up the ramp to board the airplane, Bob Anders punched me in the arm and said, “You arranged for everything, didn’t you?” He was pointing at the name lettered across the nose of the airplane. The name of our airplane was “Argau,” a region in Switzerland. We took it a sign that everything would be all right. We waited until the plane took off and had cleared Iranian airspace before we could give the thumbs up and order Bloody Marys.

By lunchtime, Julio and I were sitting in the Zurich airport restaurant waiting for our connecting flight to Germany. Some of the six dropped down and kissed the tarmac of the Zurich runway after they came down the ramp. The other passengers viewed this as rather strange behavior.

US State Department representatives met us at the other side of Swiss immigration and customs. The six were whisked away in a van to a mountain lodge; Julio and I were left standing in the parking lot. I had loaned one of them my topcoat because it was chilly. It was US Government property; Julio and I had bought European-style clothing, topcoats, and shoes for our trip to Tehran. I never retrieved the topcoat, and later was admonished by our Budget and Fiscal people when I did my accounting. Just another typical TDY. All part of the job.

Publicity

A few days later, the story hit the streets in Montreal. I was still in Germany when the story came over the Armed Forces radio station. I arrived in New York two days later, and at the airport I picked up a copy of The New York Post with the headline, “Canada to the Rescue!”

When I boarded the flight in Germany, I was carrying a large tin of Iranian caviar that the Staffords had bought for me in the departure lounge in Mehrabad. I asked the stewardess if she would keep it cold for me. She said, “No, it is either Russian or Iranian, and we don’t like either!” The Soviets had invaded Afghanistan in December, and President Carter had withdrawn from the Moscow Olympics.

Chapter 21 of the Pelletier book, The Canadian Caper, covered the impact of our success in Canada and the United States.

To the Embassy staff’s heroism was added a typically Canadian touch of modesty. It was important, said Ken Taylor in an interview later, for the Americans to say thank you. . . . They did more than that. They went wild. It was the first good news after three months of national trauma. . . . The maple leaf [Canadian flag] was flown in Oklahoma City, in Livonia, Michigan, and in a hundred other American towns and cities. Billboards sprang up throughout the American countryside with giant letters that spelled Thank You, Canada. A major US bank bought a full-page ad in The New York Times to commemorate the Canadian deed.

Jerome took out an ad in his local Burbank paper which said, “Thanks, Canada, we needed that….”

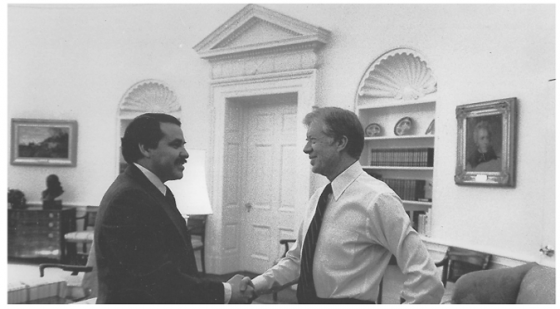

Ken Taylor became an instant hero. He was described as “the Scarlet Pimpernel of diplomacy.” He returned to Ottawa, covered in glory. Subsequently, he was involved in a whirlwind tour of appearances, some with the six. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada, received a Congressional Medal from the United States, and was awarded several honorary degrees. He lived his cover all the way.

An ironic coda: by the time Studio Six folded several weeks after the rescue, we had received 26 scripts, including some potential moneymakers. One was from Steven Spielberg.

CIA Goes Hollywood

Antonio J. Mendez

January 2019 CIA One of our most legendary Agency officers, Antonio J. “Tony” Mendez, passed away over the weekend after a brave battle with Parkinson’s disease. Perhaps best known for masterminding the daring 1980 rescue of six American diplomats from Iran, an operation made famous by the film Argo, Tony will be remembered for his patriotism, ingenuity, and lifelong commitment to our Agency’s mission.

A native of Eureka, Nevada, Tony started working for the Agency in 1965 and spent 25 years as a document counterfeiter and disguise maker in what was then called the Office of Technical Services.

During the height of the Cold War, Tony painstakingly devised a number of critical deception operations in places like Southeast Asia and the former Soviet Union.

In 1979, Tony and other CIA technical specialists created a dummy movie-production company in Hollywood and delivered disguises and documents that made possible the : The CIA closely held the story until revealing it to the public for the Agency’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1997. The 2012 award-winning film Argo, produced by and starring Ben Affleck, dramatized this story of deception and intrigue for the world to see.

Among those killed on April 25, 1980 as part of Operation Eagle Claw were three Marines: Sgt. John D. Harvey, 21, of Roanoke, Virginia; Cpl. George N. Holmes, Jr., 22, of Pine Bluff, Arkansas; and Staff Sgt. Dewey L. Johnson, 32, of Jacksonville, North Carolina.

Five service members from the Air Force were also killed in the rescue attempt. These service members include Capt. Richard L. Bakke, 34, of Long Beach, California; Capt. Harold L. Lewis, 35, of Mansfield, Connecticut; Tech. Sgt. Joel C. Mayo, 34, of Bonifay, Florida; Capt. Lynn D. McIntosh, 33, of Valdosta, Georgia; and Capt. Charles T. McMillan II, 28, of Corryton, Tennessee.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers