by Christopher L. Kolakowski

Lord Louis Mountbatten visited the battlefield of Kohima after the fighting had ended in 1944. Considering the ground and the course of the battle, he commented, “The Battle of Kohima will probably go down as one of the greatest battles in history.” Field Marshal Sir William J. Slim agreed, writing in 1956 that, “sieges have been longer but few have been more intense, and in none have the defenders deserved greater honor than the garrison of Kohima.”

For two months, from early April to early June 1944, the eastern Indian town of Kohima and its surrounding hills were the focus of very intense and dramatic back-and- forth fighting between Allied and Japanese forces. Both sides alternated offensive phases with desperate defensive fighting. Although the battle took up a relatively small area, its course affected operations from Manchuria to India and attracted attention as far away as Washington and London. Today, Kohima is known among the superlative battles of World War II.

After the Pacific War’s outbreak in December 1941, Japanese forces pushed through Thailand into Burma. In a fast campaign over the first months of 1942, the Japanese Fifteenth Army drove a mixed Chinese, Indian, and British force almost completely out of the country. At the same time, other Japanese forces secured Malaya, Singapore, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. The Fifteenth Army’s advance stopped at the Indian and Chinese borders, after having cut the last land connection to China via the Burma Road. American planes began ferrying supplies to China over the Himalayas.

READ MORE about World War II

The Allies launched two offensives in 1943: one in the Arakan in Burma that resulted in a humiliating defeat, and an inconclusive raid by a brigade (the famous Chindits) under British Brig. Orde C. Wingate. Both failed to change the strategic balance. In the last days of 1943, Sino-American forces under Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell commenced a southward advance into northern Burma to reopen a land route to China via the key town of Myitkyina.2

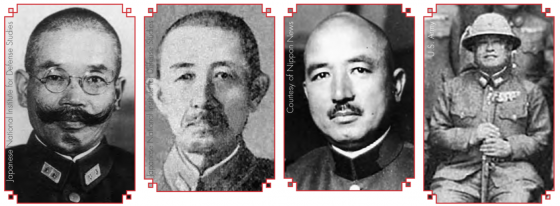

In contrast to the previous year’s defensive attitude, the Japanese in Burma thought in offensive terms for 1944. Lt. Gen. Kawabe Masakazu’s Burma Area Army held the country with forces scattered along the major invasion routes. In southwest Burma stood Lt. Gen. Sakurai Shozo’s Twenty- Eighth Army with the 54th, 55th, and 2d Divisions, the last having just recovered from a mauling at the Battle of Guadal- canal. In central Burma, the Fifteenth Armyunder Lt. Gen. Mutaguchi Renya faced India with the 15th, 31st, and 33d Divisionssupported by the division-sized Indian National Army (INA). The independent (and elite) 18th “Chrysanthemum” Divisionunder Maj. Gen. Tanaka Shinichi opposed Stilwell, and Maj. Gen. Matsuyama Yuzo’s56th Division held the Burma Road along the Burma-China border.

Wingate’s 1943 operation had inspired Mutaguchi about the feasibility of advancing across the mountains into India, specifically the border area around Imphal. Capturing Imphal and the surrounding area would eliminate a major British base in eastern India and hopefully cause restive elements of the Indian population to revolt against British rule in a larger version of 1942’s Quit India Movement. Mutaguchi also recognized that a victorious invasion of India would enhance both his personal and Japan’s national prestige, especially given the many reverses Japan suffered in the Pacific in 1943. In January 1944, Imperial General Headquarters sanctioned Mutaguchi’s plans.

March on Delhi

Throughout February, Mutaguchi’s forces made their final preparations for the advance into India. Although Tokyo portrayed theFifteenth Army’s advance as a “March on Delhi,” and Mutaguchi himself dreamed of conquering India, Kawabe’s orders limited Mutaguchi to taking Imphal and the surrounding area. While the 15th and33d Divisions and the INA attacked Imphal from three sides, Lt. Gen. Sato Kotoku’s31st Division would secure the north flank by capturing Kohima. Significantly, the Japanese left the Allied base at Dimapur, forty-five miles west of Kohima and on the key Bengal and Assam Railway, off their list of objectives. This was a major omission, as taking Dimapur would sever the major transportation artery linking Allied forces in eastern India and strangle supplies for both Stilwell’s forces and the airlift to China. The Allies did not know of this limitation and remained sensitive to any threat to Dimapur.

On 6 March, the first of Mutaguchi’s forces moved forward, with the rest following in stages over the next nine days. They faced 70,000 British troops around Imphal and the hamlets to the north, all under the command of Lt. Gen. Geoffrey Scoones’ IV Corps. Scoones answered to the Fourteenth Army under then-General William Slim, who oversaw the entire front along the India-Burma border from the Bay of Bengal to Stilwell’s advance in North Burma.

IV Corps stationed most of its strength south and east of Imphal, represented by the 17th, 20th, and 23d Indian Divisions with supporting units. Thirty miles northeast of Imphal at Ukhrul was the two-battalion 50th Parachute Brigade under Brig. M. R. J. Hope-Thomson, whereas twenty-five miles east of Kohima stood Lt. Col. William Felix

“Bruno” Brown’s 1st Assam Regiment, a locally recruited unit. The weight of Sato’s advance would encounter these two units.

Slim knew Mutaguchi’s offensive was coming; he planned a phased withdrawal to Imphal to fight the decisive battle there. However, General Scoones was to decide the timing of the movement. The battle developed gradually, causing Scoones to order the withdrawal at a point almost too late. Moving with speed and ferocity, the Japanese soon pressed IV Corps back toward Imphal. South of town, the 17th Indian Division fought its way out of encirclement twice to reach Imphal. At the end of March, Japanese forces cut the Imphal-Kohima Road, isolating IV Corps.7

Meanwhile, the 15,000 men of Sato’s 31st Division slashed their way into India. The division formed three columns, centered on each of its three component regiments: 58thon the left, 124th in the center, and 138thon the right. Their advance crossed several parallel mountain ranges, each over 5,000 feet in elevation. “In general, the advance of the Division was relatively smooth,” noted a staff report, “but the transportation of supplies through the rugged mountain ranges was extremely difficult . . . The men also suffered from exhaustion and malnutrition.”

Sato’s left column brushed up against Hope-Thomson’s paratroopers at Sangshak, near Ukhrul. Although outside his zone of operations, the column commander, Maj. Gen. Miyazaki Shigesaburo, diverted southward and attacked Sangshak on 22 March. Over four days the Japanese stormed successive hill positions as the paratroopers held on tenaciously. On the morning of 27 March, Hope-Thomson’s men cut their way out to Imphal. The battle cost the Japanese 500 casualties and 5 precious days.

Further north, the Japanese 138th Regi- ment encountered Brown’s Assam Regiment. The main body held Jessami with Lt. John “Jock” Young’s A Company defending an outpost at Kharasom. Brown and Young had orders to fight “to the last man and the last round.” Both places received attacks on 26 March, and over the next five days both units held their own. But they had lost communi- cation with Kohima, and recall orders could not be issued. A U.S. colonel flew a Piper Cub to airdrop orders, which Brown finally received on 31 March; he pulled back 1 April. Young never got the message, but on his own ordered his men out. “I shall be the last man,” he declared, and with difficulty got his company moving toward Kohima. No one ever saw Young alive again, nor was his body identified. But these sacrifices were not in vain—they delayed the Japanese advance another five critical days.

Slim well understood the importance of these developments. A captured Japanese order from Sangshak confirmed his worst fears. “Within a week of the start of the Japanese offensive,” he recalled, “it became clear that the situation in the Kohima area was likely to be even more dangerous than that at Imphal. Not only were the enemy columns closing in on Kohima at much greater speed than I had expected, but they were obviously in much greater strength.” Slim had expected a strike toward Kohima by a Japanese regiment, but the entire31st Division was on its way. “We were not prepared for so heavy a thrust,” Slim admitted. “Kohima with its rather scratch garrison and, what was worse, Dimapur with no garrison at all, were in deadly peril.”

Slim needed reinforcements in a hurry. He asked his superiors, General Sir George Giffard of 11th Army Group and Supreme Commander of Southeast Asia Command Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, for air transport. Mountbatten directed thirty U.S. aircraft be diverted from ferrying supplies to China to fly the 5th Indian Division into Imphal from the Arakan. In one of the first strategic air movements of its type, two brigades and the divisional troops flew into Imphal over seven days, 19–26 March. The division’s third brigade, Brig. D. F. W. Warren’s 161st, had been diverted to Dimapur and Kohima, and arrived in late March to assist the defense. Lt. Gen. Montagu G. N. Stopford’s 33 Corps Headquarters and Maj. Gen. John M. L. Grover’s 2d British Division, both training in southern India, also started for Dimapur.

At Stilwell’s request, Allied commanders met at Jorhat on 3 April to discuss the situation. Stilwell offered Slim the elite Chinese 38th Division to help hold Dimapur and the railroad. Stilwell warned, “it would mean stopping his advance, probably withdrawing, and certainly not getting Myitkyina before the monsoon,” recalled Slim. “I was sure this was Stilwell’s great opportunity. I, therefore, told him to retain the 38th Division . . . and to push on to Myitkyina as hard as he could go.”

Stopford arrived on the scene 23 March, although his headquarters did not formally open until 3 April. Slim gave him several missions, starting with protecting Dimapur and the railroad. Once done, his corps was to reopen the road to Imphal. Grover’s division was on the way, but for the moment Stop- ford’s only field force was Warren’s brigade, just arriving at Kohima. Stopford felt that even though holding Kohima was of major importance, Dimapur was the more critical position to defend. Despite protests from local commanders, the 161st received orders to retrace its steps to Dimapur. On 31 March, Warren’s men retired to Nichugard Pass, ten miles east of Dimapur. Over the next days, elements of the 2d British Division arrived on the scene to reinforce the Dimapur defenses. On 4 April, the 161st Brigade was ordered back to Kohima.

Warren’s men promptly got back on the road. By the time his lead battalion, the 450 men of Lt. Col. John Laverty’s 4 Royal West Kent (4 RWK), reached Kohima, the siege was underway.

SIEGE

Kohima town sits at a pass that provides the vital link between Imphal and the interior of India. The town and its namesake ridge sit along and astride the key Imphal-Dimapur Road, and several other tracks into the hills all intersect at Kohima. The area has traditionally been a communication route between Burma and India, and had been the scene of fighting in the 1870s.

Kohima Ridge is really a series of hills running north-south along the road to Imphal. Gently sloping saddles connect each feature. Since development as a supply base a year earlier, some of its various hills had become known by their function. From south to north, they were GPT (General Purpose Transport) Ridge, Jail Hill, DIS (Detail Issue Store), FSD (Field Supply Depot), Kuki Picquet, and Garrison Hill. A northwest extension of Garrison Hill housed a hospital and became known as IGH (Indian General Hospital) Spur. Thick woods, interspersed with the town’s and base’s structures, covered most of these hills. Garrison Hill was terraced and landscaped, and included the home (complete with clubhouse and tennis court) of the deputy commissioner for the area, Charles Pawsey. The Imphal-Dimapur Road skirted the ridge to the east before turning west past Garrison Hill. Treasury Hill and a Naga Village settlement overlooked the ridge from the northeast; those heights also extended north to the hamlet of Merema. Southward loomed the imposing Pulebadze Mountain, whereas three miles to the west rose a knoll topped by the village of Jotsoma. Kohima Ridge thus was overlooked by surrounding heights: Pulebadze to the south, Jotsoma to the west, and the Naga Village/Merema to the east and northeast.

On 22 March, Col. Hugh Richards arrived from Delhi to take command of the garrison at Kohima. He faced the daunting problem of organizing a defense with limited combat troops and constantly changing forces. Richards quickly determined to concentrate his limited forces on Kohima Ridge itself. He sent away most of the logistical troops, evacuated the hospitals, and organized the men in the replacement depot into platoons to be assigned to combat units. Richards was the one who recalled the Assam Regiment, and protested Warren’s withdrawal to Dimapur. He also unsuccessfully sought to keep a battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment that had orders for Imphal.

One advantage Richards enjoyed was the loyalty of the local Naga people. Throughout the battle they assisted the British as guides, porters, and spies. Pawsey had spent years among them as Deputy Commissioner, and did not want to abandon what he regarded as his people. He also understood that if he left, the British would lose face forever. The Nagas recognized his importance; “Charles Pawsey,” affirmed one, “was one of the reasons the Nagas remained loyal to the British . . . His action at a critical time improved the image for the British administration.” Pawsey remained at Richards’ side through the battle. Thanks to intelligence from the Nagas, Richards could track the Japanese approach.

Sato planned a two-pronged advance on Kohima. Miyazaki and the 58th would drive straight up the Imphal road, while the 138thsecured the Naga Village and swung around behind Kohima to cut the road to Dimapur. The 124th would be in reserve.

On 3 April, Brown brought the Assam Regiment into the perimeter. Of 500 men who started the campaign, 280 remained, but they were a welcome reinforcement. The next day, Richards’ outposts made first contact with the Japanese. The West Kent, plus a company from 4th Battalion, 7th Rajput Regiment, arrived with artil- lery in the late afternoon of 5 April before the Japanese closed the road west after sundown. This left Richards with 2,500 men, 1,000 of which were noncombatants. The garrison’s combat strength centered on 4 RWK, assisted by the Assam Regiment, five detached companies of Indian infantry, a battalion of the paramilitary Assam Rifles, and the half-trained Nepalese Shere Regiment. There was plenty of ammunition and food to last for weeks, although water was short.

Warren led the rest of his troops forward and found Japanese shellfire already striking around Garrison Hill. He quickly realized his entire brigade could not fit into the perimeter; he took position at Jotsoma and formed an all-around defense. His artillery would assist the defense of both Jotsoma and Kohima.

Kohima faced its first test on the evening of 5 April, as Miyazaki’s men attacked GPT Ridge and Jail Hill. The latter held out, whereas the troops defending the former gave way and retired toward Dimapur. The Japanese swung east and repeatedly attacked Jail Hill on the 6th, forcing its evacuation. That night, a company of 4 RWK wiped out a Japanese penetration into the structures between FSD and DIS; an exploding ammu- nition dump flushed many Japanese into the open where the British gunned them down. Daylight on 7 April revealed forty-four Japanese bodies in the defile between the hills. Other Japanese had sheltered in the tandoor ovens of a bakery, and L. Cpl. John P. Harman went in with grenades, dropping one into each oven. Two men, including an officer, survived and Harman captured them. He carried them back to British lines over his shoulder like logs. The British found the officer had a map of Japanese artillery positions around Kohima. “This is even worse than Sangshak,” some of the Japanese prisoners complained, surprised at the defense’s steadfastness.

After forty-eight hours, the pattern of the siege grew apparent. The Japanese would fire furiously at dusk in what the defenders called the “evening hate.” Repeated night attacks denied anything but the most fitful sleep, whereas during the day, snipers, machine guns, artillery, and mortars harassed Kohima’s defenders. British artillery from Jotsoma, aided by spotters in Kohima’s perimeter, engaged the enemy as needed. The loss of GPT also meant the loss of most of the garrison’s water access except for a small spring on Garrison Hill; Richards’ had to limit his defenders to one pint of water per man per day.

Japanese attention next shifted to Garrison Hill, as elements of two Japanese battalions attacked up the terraced slopes from the Naga Village against the reinforced company holding the terraces. Mortar fire blanketed the British positions as the Japanese pressed upward. Indian Bren gunners defended to the last as the tide washed over them. Pawsey’s residence fell, and the defenders, reinforced by A Company of the West Kent, took position at the tennis court.

Supporting fire came from the clubhouse, with a pool table and other furniture providing platforms for the Brens. There the Japanese surge stopped, leaving the width of the tennis court between the two sides. These lines would not move for weeks.

Farther south, the Japanese had placed a machine gun overlooking DIS that threat- ened to make the British position untenable. In broad daylight, Harman single-handedly attacked the position and killed the crew. He hoisted the gun over his shoulder and started back to the lines, seemingly unconcerned about the danger. A heretofore hidden Japanese machine gun shot him dead. This action, plus the one at the bakery the day before, earned Harman a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Meanwhile, Grover’s 2d Division struggled to open the road. On 8 April, Sato’s 138th Regiment had reached Zubza, thirty-two miles from Dimapur, and set up several defended roadblocks in the ten miles between Zubza and Jotsoma. Warren tried to break out westward, but found the defenses too strong; he also needed to defend his artillery position. Grover’s British troops would have to fight their way in.

Despite Stopford’s urging to take risks, Grover was torn between the imperative of relieving Kohima or protecting the road to Dimapur with only two of his three brigades on the scene. He posted Brig. J. D. Shapland’s 6th Brigade along the road and sent his lead brigade, the 5th under Brig. Victor Hawkins, forward. With tank support from M3 Grants, the infantry slowly advanced toward Jotsoma.

Richards and Laverty tracked these movements via the 4 RWK’s headquar- ters’ radio link to Warren. Laverty was somewhat jealous of his prerogatives regarding his battalion, and maintained control of this connection to the outside throughout the siege. This tension between the two senior officers did not matter much, as Capt. Tom Coates of the West Kent explained. “The siege was primarily a privates’ battle,” he recalled, “and our success was due mainly to the very high morale and steadiness of the NCOs [noncommissioned officers] and men.”

The garrison weathered more attacks over the next four days. Despite the enemy’s best efforts to break through, the lines held. But casualties mounted, and it forced Richards to abandon DIS. Meanwhile, more wounded crowded into IGH Spur, filling the area behind the sector held by Brown’s Assam Regiment. There, doctors led by the indefatigable Lt. Col. John Young, did what they could despite enemy activity and scarce water. Medical supplies were running low, and Japanese shelling made the situation at the hospital worse. Aircraft had dropped some water canisters to the garrison with mixed success, but the wounded needed more than water. Young appealed to Richards, who on the evening of 12 April asked for an airdrop of medical supplies, to which Laverty added mortar ammunition and grenades.

That night, the garrison repelled another attack. On the morning of 13 April, the Japanese deliberately shelled IGH Spur, inflicting over fifty casualties on already wounded men and killing three doctors. In the afternoon, the drumming of aircraft engines could be heard from the west. Three U.S. C–47s appeared and came in low over the ridge. They parachuted water and the requested supplies, but almost all of it drifted into the Japanese lines. The Japanese used some captured mortars to shell Kohima’s defenders with the airdropped rounds. A little later, Royal Air Force (RAF) transports successfully dropped ammunition and medical supplies to the garrison, but the ammunition had been meant for the artillery at Jotsoma and was the wrong caliber for any of Kohima’s guns.

These developments, plus the weeklong strain of constant siege, sapped the garrison’s morale. The 4 RWK war diary called this day “The Black Thirteenth.” Richards sensed the mood and issued an order of the day. “The relief force is on its way,” Richards told his men, “and all that is necessary for the Garrison now is to stand firm, hold its fire and beat off any attempt to infiltrate among us. By your acts you have shown what you can do . . . I congratulate you on your magnificent effort and am confident that it will be sustained.”

That night, the Japanese attacked the garrison from north and south. They got within the trenches on FSD, held by two understrength 4 RWK companies. In close- quarters combat, which in one case involved a man strangling a Japanese officer with his bare hands, the defenders drove off the attackers. At the tennis court, B Company of the 4 RWK endured repeated attacks. A Bren gun jammed, and some Japanese rushed the position; the gunner died but another soldier beat off the attackers with a shovel. The Assam Regiment reinforced the sector the next day.

For Kohima’s defenders, the next few days were blurs of shelling, sniping, and attacks from Japanese troops. Artillery from Jotsoma and RAF Hurricane fighter- bombers lent their firepower to the defense when possible. Thirst increased despite rain coming on 14 April, as there were few facilities to catch the water. Blasted trees no longer gave shelter from the weather or concealment from the enemy, and many snared supply parachutes. But the garrison stood firm because of the sights and sounds to the west.28

As Kohima endured, Hawkins’ brigade fought to open the road. Rain slowed perations and limited the use of tanks. On the 14th, Warren promised Laverty and Richards: “I’m doing my best, but intend to make a proper job of it.” Late that day, Hawkins launched an attack on the last posi- tion between his men and Jotsoma; it fell the next morning. At 1100 on 15 April the 5th Brigade and 161st Brigade joined hands.

Warren signaled this news to Kohima, and promised relief on the 16th. He sent 1st Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment (1/1 Punjab) attacking eastward with some success. But Grover arrived in the afternoon and postponed the final relief attack for one day, citing lack of “time for recce [reconnais- sance] . . . and lack of adequate provision for the security of the right flank of the brigade.” Warren regarded those as acceptable risks in view of the garrison’s condition, but had to acquiesce to the postponement. The British defeated the Japanese attacks on the road on 16 April, but the threat of being cut off remained. Despite only a mile or so remaining to Garrison Hill, on the morning of 17 April, Warren postponed his relief effort yet another day.

The garrison’s morale wavered at these repeated delays of rescue. Grim jokes about help never arriving circulated among the soldiers, and both officers and men began to lose confidence they would get out of Kohima alive. In the hospital, wounded officers asked for their sidearms back—they wanted a quick end when the Japanese came.

On the night of 17 April, the Japanese preceded a mass charge against FSD with heavy artillery fire. The exhausted defenders reeled backward and were pushed off both FSD and Kuki Piquet by the early hours of 18 April. “We couldn’t do a thing sir,” reported a West Kent soldier to an officer on Garrison Hill. “The Japs were simply all over us.”

This defeat left Richards and his garrison with a perimeter roughly 350 yards wide by 350 yards deep, centered on Garrison Hill. There was no further retreat possible; it was do or die. Every man who could, including the wounded and Richards himself, took a weapon and went to the line. The defenders peered into the darkness and braced for an assault. Dawn would save them, but hours of darkness remained.

As they waited, a young soldier turned to Richards. “Sir, can I ask you a question?” “Of course,” Richards replied. “What is it?”

“When we die, sir, is that the end or do we go on?”

Phase II

Dawn broke on 18 April without a Japanese attack. Instead, British artillery and air strikes hammered Japanese positions in the surrounding hills. The garrison saw tanks and infantry advancing from the west. The relief force cleared a roadblock at mile marker forty-five, then clawed its way east toward Garrison Hill. Shortly before noon, the infantry, 1/1 Punjab of Warren’s brigade, reached IGH. The siege had been broken.

Immediately after the linkup, Young began evacuating the wounded into waiting trucks, which sped them to Dimapur. Over the next two days, fresh troops from Shap- land’s 6th Brigade replaced Kohima’s weary and exhausted defenders. The Japanese made half-hearted attempts to attack, but the relief went on without interruption. Richards finally left on 20 April after handing over command to Shapland himself.34

Garrison Hill’s appearance shocked Shapland’s troops. “The place stank,” recalled Maj. John Nettlefield. “The ground everywhere was ploughed up with shell-fire and human remains lay rotting as the battle raged over them. . . . Men retched as they dug in.” The amount of wreckage impressed others. “It was possible to pick up anything from a Tommy-gun to a pair of ladies’ shoes,” noted Lt. Col. Wilbur Bickford, commanding the 1st Royal Berkshire. “The place was a veritable paradise for flies.”

Kohima’s relief came at a bad time for Sato. Not only had he failed to fully capture Kohima Ridge, he now received orders from Mutaguchi to detach three battalions of infantry and one of artillery under Miyazaki to Imphal, where Mutaguchi planned to use them to break into IV Corps’ perimeter from the north. Sato assembled the force, two battalions of the 124th, one of the 138th, and 3d Battalion of the 31st Mountain Regi- ment, south of Pulebadze near the village of Aradura. Meanwhile, the rest of the 138th and 124th, bloodied in battles along the road, fell back to defensive positions at Merema and Kohima. The 58th held its ground on Kohima Ridge, and Sato decided to use its ebbing strength to attack Garrison Hill one more time.

General Grover also took this time to deploy his division and decide his next move. Captured documents revealed both Mutaguchi’s orders for the detachment and Sato’s plans to comply. Prodded by Slim and Stopford, who were in turn pushed by messages from Washington and London, Grover decided to attack with his entire division. Hawkins would move to Merema and then south of Kohima, while Shapland would attack from Garrison Hill outward. Brig. Willie Goschen’s 4th Brigade (minus one battalion remaining to protect the road) would march from Jotsoma to Pulebadze in an effort to flank Sato’s troops to the south. Warren’s tired force would help protect the road to Dimapur.

Sato’s men attacked Garrison Hill, now held by the 1st Royal Berkshire and 2d Durham Light Infantry (DLI), on 23 April. The Royal Berkshire at the tennis court held firm, and the DLI fought a back-and- forth action that ended with the defenders back in their positions after hours of heavy fighting. For the Japanese, the fighting had wiped out nearly four of the seven attacking companies, and those losses were irreplace- able. Sato realized that if he detached the forces Mutaguchi wanted, his division would likely be unable to hold its positions around Kohima, which was essential to preventing Imphal’s relief. He cancelled Miyazaki’s marching orders and ordered all of his units to the defensive.

Meanwhile, Grover’s brigades moved forward. After trying and failing to get tanks up the back side of Garrison Hill, Shapland’s infantry secured positions overlooking the intersection below Pawsey’s house. Although the Japanese still held the terrace itself, tanks could now round the bend and come up Pawsey’s driveway—although not imme- diately as it took several days under fire for engineers to regrade a curve in the driveway to fit a Grant tank. Farther north, Hawkins’ brigade reached Merema and probed south- ward toward the Naga Village. To the south, Goschen’s infantrymen encountered little opposition but the terrain slowed their pace to a crawl. “It was a case of up one steep khud [ridge] and down the other side, then up a steeper and down again,” recalled an officer. “To anyone who hasn’t soldiered in Assam the physical hammering one takes is difficult to understand. The heat, the humidity, the altitude, and the slope of almost every foot of ground, combine to knock hell out of the stoutest constitution.” Rain, intermittent to this point, started in earnest on 28 April; it rained at least once every day for the rest of the battle.

Grover had expected to have cleared Kohima by 30 April, but the slow pace of operations forced him to recast his plans. On 4 May, the earliest 4th Brigade could be ready, he sent his entire division forward. During the night, Hawkins’ 5th Brigade, every man wearing gym shoes, infiltrated the Naga Village and occupied the north- west portion early on 5 May. The brigade repelled repeated ferocious counterattacks. In the center, Shapland’s infantry failed to dislodge Kuki Picquet’s defenders although the DLI managed to get atop FSD for a short time. Supported by tanks and elements of Warren’s brigade, a renewed attack cleared all but the eastern slopes of Kuki Picquet and FSD by dusk on 7 May.

Farther south, Goschen’s men ran into the 124th Infantry, having been sent by Sato to GPT to prevent just such a flanking move. The 2d Royal Norfolk, in the lead of the column, encountered several Japanese bunkers whose fire held up the advance. Capt. John Niel Randle, in command of the battalion’s B Company despite wounds, attacked and destroyed a bunker, using his dying body to block the embrasure so his company could advance. He received a posthumous Victoria Cross, the second of two awarded at Kohima. By 7 May, GPT’s crest was in British hands.

At this point, Grover’s advance paused as other units joined the action. To the east, 23d Brigade of the Chindits advanced into Sato’s rear. To Kohima came the independent 268th Lorried Infantry Brigade to relieve some of Grover’s units for a short rest. Maj. Gen. Frank Messervy’s 7th Indian Division headquarters, the division artillery, and the 33d and 114th Indian Infantry Brigades also began arriving on the scene. The 33d Brigade reinforced the area around FSD.

Sato, on the other hand, had received nothing in the way of supplies or replace- ments for his mounting casualties. Several of his infantry units had sustained fifty percent or greater losses, and all of his men were starving to some degree. By mid-May “only a small amount of ammunition remained, reserves of provisions as well as forage were dangerously low, and local stocks of food were practically exhausted,” noted a staff report. “The Division was, in fact, rapidly losing its offensive ability.”

After a period of regrouping, on 11 May the British attacked all along the line. They cleared the tennis court and all of Kohima Ridge in three days of heavy fighting. Hawkins fell wounded as his brigade fought against dogged resistance to advance in the Naga Village. Gurkhas of 33d Brigade stormed Jail Hill and cleared it by 14 May. Parts of Messervy’s 7th Indian Division attacked the Naga Village the following week, and by 26 May virtually all of the Japanese positions in and around Kohima had been captured. Stopford could now turn his divisions southward to exploit the victory and open the road to Imphal.

Sato understood what these developments meant. His division had suffered losses that made it a shadow of its former self. The monsoon was starting, and his tenuous overland communications became more fragile by the day. On 25 May, he signaled Mutaguchi his intention to withdraw unless supplies arrived within days. None came, so on 31 May, Sato ordered his men to leave Kohima. Most would go east, with a battalion-sized group under Miyazaki to fight a delaying action along the road to Imphal. “Retreat and I will court-martial you,” radioed Mutaguchi when informed of these orders. “Do as you please,” Sato shot back. “I will bring you down with me.”

Pursuit

On 2 June, Sato’s headquarters and infantry abandoned the Naga Village. After a sharp fight in the Aradura area, Miyazaki’s men retired southward toward Imphal on 5 June. The British detected the slackening of Japa- nese resistance, and Stopford urged his two division commanders, Grover and Messervy, to press the attack. Messervy moved his division east and southeast toward Jessami and Ukhrul, while Grover directed his men south along the Imphal Road. The IV Corps position was seventy-five miles away.

“As the advance progressed, the magni- tude of the Japanese defeat began to be realized,” recalled Brig. M. R. Roberts, whose 114th Brigade led the 7th Indian Division’s advance. “Arms, equipment, and guns were found abandoned along the track in increasing quantities.” Sato’s retreat was becoming a rout.

Messervy’s men found worse as they penetrated deeper into Sato’s rear areas. “In their cautious progress, the brigade passed through and around deserted camps of leafy huts, concealed strongpoints, living accom- modation for thousands,” recalled an officer of the division artillery. “Unburied dead lay everywhere, many untouched, some fat and well-looking, others emaciated, filthy skeletons. Typhus, that scourge of armies, had done its work . . .

Meanwhile, Grover’s 2d Division started southward toward Imphal. Miyazaki’s men took up bridges, laid mines, and set up road- blocks on the narrow and twisty road, but the British kept a close pursuit. The Japanese stood at the villages of Viswema and Mao Songsang, where the road narrowed between heights to the west and a deep valley to the east. Both times British infantry flanked the Japanese position and forced a retreat. Grover alternated brigades to always keep a fresh unit at the front of the pursuit.

By 18 June, the 2d Division stood just north of Maram, at mile marker eighty on the road and forty miles from Imphal. There, Miyazaki had organized a roadblock he thought could hold for ten days. The 5th Brigade attacked down the road under cover of smoke and air strikes, while a bulldozer followed behind to clear the block. The position fell within hours, and the Japanese fled eastward. The 4th Brigade passed through and advanced another eight miles before overrunning the15th Division’s headquarters. The 6th Brigade next took up the advance.

On 22 June at 1030, the DLI met advance elements of 5th Indian Division at mile marker 109 in Kangpokpi. After eighty-five days of isolation, IV Corps at Imphal again had land communication with the outside world. That night, a truck convoy drove from Kohima to Imphal with headlights blazing.

Imphal’s relief signaled the final failure of Mutaguchi’s invasion. In early July, he accepted defeat and ordered his battered forces back to Burma. “All hope of capturing Imphal or Palel was now gone,” stated a staff report, “and the Fifteenth Army realized it would be fortunate if it could extricate itself from its extremely hazardous position without greater losses.” Within a month of Imphal’s relief, the troops of Fifteenth Armyhad almost completely abandoned India. The dream of a March on Delhi was gone.

Conclusion

The Battle of Kohima proper lasted two months, from 5 April to 5 June 1944. In the two months of combat, the British lost 4,064 casualties. Richards’ garrison contributed 401 to this total, whereas the 161st Brigade lost 462—a combined approximate total of one in three. Grover’s 15,000-man 2d Division lost 2,125 men around Kohima, and Messervy’s division lost 623 of 12,000 in three weeks of battle and one month of pursuit. As for the Japanese, Sato took 15,000 men into India; 6,264 were killed, wounded, or died of disease. Another 2,800 required immediate hospitalization upon returning to Burma, leaving only 5,936 men fit for duty at the end.

Kohima also cost the two principal division commanders their jobs. On 4 July, Stopford, increasingly dissatisfied with Grover’s methods, relieved the 2d Division commander and sent him home to Britain. The next day, the Japanese removed Sato from command of the 31st Division; “I do not intend to be censured by anyone,” Sato announced to his staff. “Our 31st Divisionhas done its duty.” After several months of staff duty in Burma, officials sent him home on a medical furlough and he saw no further active service.

Kohima was the high-water mark of Japa- nese fortunes in Southeast Asia. Sato’s retreat started a yearlong rollback of the Japanese front line that ended with the liberation of Rangoon in May 1945. Never again would the Japanese wield the initiative in Southeast Asia as they did during the thrust into India.

Had Richards’ gallant defenders been overrun, the Japanese could have blocked any attempt to relieve Imphal for some time, perhaps permanently. They also would have threatened Dimapur and its railway, and certainly been in a position to block the line with detachments. This hazard alone would have affected the supplies going to Stilwell and China. Less supplies on the railroad would have slowed or stopped air operations in China, and the pace of Stilwell’s campaign against Myitkyina. Victory in Kohima ensured that these things did not happen.

Today, Britain remembers Kohima, along with Imphal, as one of its greatest battles of all time. The Kohima Museum in York, England recalls the battle and the 2d Divi- sion. Japan recognizes Imphal-Kohima as one of its worst defeats, but also one of its larger battles; each year Japanese tourists come to visit the battlefields and often hunt for the remains of relatives lost in the inva- sion. India has somewhat belatedly recog- nized the importance of these engagements, and local preservation and tourism efforts are underway to promote their importance.

Garrison Hill now lies in the middle of Kohima, which has grown to engulf most of the 1944 battlefield. The area around the Pawsey residence is now the Kohima War Cemetery, maintained by the Common- wealth War Graves Commission. The terraces remain, and now hold 1,421 graves of those who fought on and around that hill. The battle’s 917 Hindu dead, since cremated, are also remembered. Stones also mark the precise location of the famous tennis court, which is next to the cemetery’s Cross of Remembrance. It is a focal point of visits to the cemetery and the battlefield.

At Garrison Hill’s base is a monument to the 2d Division, made of stone from a nearby quarry. It contains an inscription by John Maxwell Edmonds that today is known as the Kohima Epitaph. It charges the viewer and offers a timeless reminder:

When you go home tell them of us and say for your tomorrow we gave our today.

Christopher L. Kolakowski is the director of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum. He has written numerous books, and is an honorary colonel of the 116th Infantry Regiment of Virginia National Guard.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers