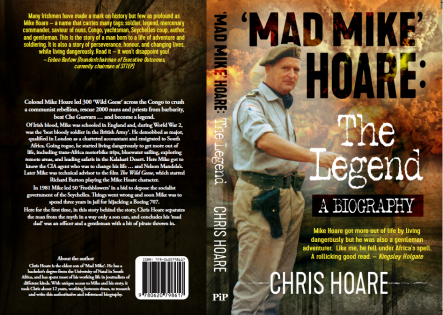

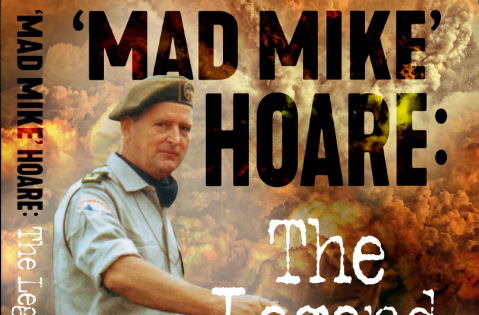

By Chris Hoare Author of Mad Mike Hoare

Fifty years ago, Stanleyville in the Congo was the scene of one of the most savage crimes of the last century, the cold-blooded massacre of hostages by the Simba rebels.

Mercenary soldiers from 5 Commando under the leadership of Lt Colonel Mike Hoare, probably the most famous merc officer since World War 2, had been unable to prevent the tragedy. But in the days to come, they saved hundreds of hostages from a tortured death, and helped restore peace to that troubled land.

There were nearly 300 white hostages imprisoned in the Victoria Hotel when the sun rose over Stanleyville, now Kisangani, on 24 November 1964. A few hours later, seconds before their rescuers arrived, many lay dead, brutally hacked to death or shot by their rebel captors. Others, the lucky ones, would thank God later that day that they had survived the premeditated and cold-blooded slaughter.

The Congo had been engulfed by a communist-backed armed rebellion in early 1964, after four years of independence from Belgium. The Reds wanted the vast mineral wealth of the Congo, but America in the form of the CIA stepped in and, assisted by Belgium, funded a mercenary army whose objective was to keep the Congo aligned to Western interests. It was Prime Minister Moise Tshombe who called in white soldiers of fortune, mainly South Africans, to support the hopeless Congolese army – it was common knowledge that the Congolese used to reverse into battle so that they could make a quick and easy getaway when the going got rough!

Col Hoare commanded the 300-strong strike force which he dubbed ‘The Wild Geese’. He was born into an Irish seafaring family, but served in the British army during World War 2. An entry in his war record describes him as “a forceful and aggressive type who will go far”. He was demobbed as a major at the age of 27 in 1946, and emigrated to South Africa, believing that you get more out of life by living dangerously. Short, dapper, well-read, and with a generous sense of humor, he was usually described as “an officer and a gentleman”.

But even as hundreds of men were signing up in Johannesburg and Salisbury, the situation in Congo was deteriorating. On 5 August 1964, as Colonel Hoare later wrote: “A column of 60 motor vehicles descended on Stanleyville, led by a handful of prancing witchdoctors, waving palm leaves before them and chanting incantations. The population was spellbound. The 1000-strong garrison of the city, terrified by the sight of witchdoctors in their full regalia and rag-tag army of rebels dressed in monkey-skin caps and feathers, fled in disarray, flinging their arms into the Congo River as they went. The city was closed to all comers and nobody was allowed to enter or leave, including the staffs of the various consulates. For the next 111 days, government was at the whim of a handful of semi-educated megalomaniacs, drunk with power, uncertain of their aims and incapable of maintaining the slightest vestige of discipline within their ranks.

“Daily, dozens of Congolese were killed. The mayor of Stanleyville, Sylvere Bondekwe, a greatly respected and powerful man, was forced to stand naked before a frenzied crowd of Simbas while one of them cut out his liver. This was given to the mob to eat, still hot and throbbing, as the victim died in agony before their eyes.

“Among the prisoners in Stanleyville were the entire staff of the American consulate, all arrested in defiance of diplomatic convention, and held in jail for no reason other than that their lives were a means of preserving the tottering rebel regime. But the full fury of the rebel government fell on the unfortunate Dr Paul Carlson, an American whose life had been devoted to the healing of sick Congolese.” On two occasions he was sentenced to death “for spying”, but execution had been stayed at the last moment when the rebels realised his life represented a further bargaining counter against the Leopoldville government.

Meanwhile 5 Commando, spearheading a column of Congolese army troops and Belgian mercenaries, and using blitzkrieg tactics, were fighting their way up from the south of the country. Then they were ordered to wait – clearly something big was brewing. On 23 November, they got to a point 300 km from Stanleyville. That afternoon final orders arrived from Colonel Frederic Vanderwalle, the Belgian in overall command of the column. Belgian paratroops were to drop on Stanleyville at 06h00 the next day, and 5 Commando was to lead the attack from the south at the same time. Their mission was to rescue the hostages and free Stanleyville from the grip of Simba terror. Just then a tropical downpour hit the column, reducing visibility to a few metres. When it abated the column rolled forward, making its way along a rough road fringed with dripping jungle, towards Stanleyville. As darkness closed in they ran into the first of many ambushes. Sergeant Freddy Basson was killed and two men seriously wounded. Then George Clay, CBS’s Africa correspondent, was shot through the head while recording. Hoare stopped the column, “para-drop or no para-drop”.

Of the march he later wrote: “I salute every man who took part in column that night. It was the most terrifying and harrowing experience of my life.” At first light they continued the race for Stanleyville, but they were 30 km from the town when they got a message: “Paras dropped on Stan 06h35.” At the hotel, the hostages had long since given up hope. They had lived for 111 days at the whim of an unpredictable and primitive people and had now settled back into passive fatalism. Only the previous day, Le Martyr, the rebel newspaper, had raved: “We shall cut out the hearts of the Americans and Belgians and we shall wear them as fetishes. We shall dress ourselves in the skins of Americans and Belgians.”

At 07h00 the Simbas started ordering the hostages out of the hotel and on to the street. About 50 managed to hide on the upper floors of the building. Colonel Joseph Opepe was in charge of the dozen or so Simba guards who were armed with automatic weapons. Opepe had been friendly to the hostages, and to some it seemed he was stalling for time. However, his men taunted the hostages, saying: “Your brothers have come from the sky, you will be killed now.”

The sound of firing grew louder. The paras would be there within minutes. Then the order to march came and the hostages, in a column of about 80 ranks, three abreast, shuffled off at funereal pace. No one spoke, and as they walked the guards continued to demand the order to kill them from Opepe. After two blocks they heard a tremendous burst of gunfire from the paras. The Simbas ordered the hostages to sit down. As the paras drew nearer there was another loud burst. They were only a few blocks from the hostages. Again the guards, now nervous, wanted to shoot the hostages, but Opepe wouldn’t have it. ‘Major’ Bubu, a deaf and dumb mongoloid dressed in a monkey-skin robe, arrived. Then, at the next intersection, Simbas could be seen fleeing from the paras. Bubu stood gesticulating in front of prisoners. “Kill, kill,” he grunted in pantomime, acting out his orders in an inarticulate frenzy until someone fired a shot. It was the signal for the massacre to begin. Machine-guns blazed out at point-blank range as the Simbas carefully selected women and children as their first targets. A Belgian girl of six was cut in half by a hail of bullets. A Belgian priest had his leg severed above the ankle and bled to death. Phyllis Rine, an American, was wounded and bled to death. After the initial shock the prisoners broke and ran. Some were trapped and brutally killed. Dr Carlson dashed for cover but was gunned down as he leaped over a low wall. A bullet had struck his temple. Michael Hoyt, the American Consul, escaped. Later Col Hoare recorded: “It was all over in four minutes. Then the paras came. But for them, every man, woman and child held in Stanleyville that day would most certainly have met their death. They found over 80 people dead and wounded on the ground. Twenty-seven would never move again. It was an act of unparalleled savagery.”

Reflecting recently, Colonel Hoare said, “Taking Stanleyville was the greatest achievement of The Wild Geese. There is only so much a small unit of 300 men can do, but here we were part of a very big push and clearing the rebels out of Stan was a major victory for our side.”

Did he have any regrets about the massacre? “We experienced a lot of delays on the road north, and every day we would hear of more senseless killings by the rebels. It was immensely frustrating, and we were so keyed up we could not sleep. At one point I was almost persuaded to race into Stan and free the hostages, but I am convinced the rebels would have slaughtered everyone in sight. Sticking to the bigger plan, as we did, was the right thing to do.”

Meanwhile, probably about 2000 hostages were still being held in the area around Stanleyville, but rescuing hostages was not part of the military intention. Col Hoare and some of his men, however, agreed to get these missionaries, traders and civilians out. At Isangi, 150km from Stanleyville and deep in enemy territory, they rescued a large number of Congolese Roman Catholic nuns who “were petrified with fear. Many of them wept copiously and had to be coaxed out of hiding.” Their white counterparts had been taken to Yangambi, some distance away. The mercenaries fought their way to the mission. “What I saw tore my heart,” Colonel Hoare wrote. “The room was full of nuns and priests so badly bruised and beaten that some were difficult to recognize as normal human beings. A young nun in strips of clothing stumbled to the door, and with tears in her eyes, flung her arms around my neck and kissed me on the cheek. She may have been beautiful once. ‘God has answered our prayers, God has answered our prayers,’ she cried out over and over again.”

Looking back today, Colonel Hoare is proud of the rescues. “It was emotionally grueling work, seeing the way the hostages had been abused – we could see some of the nuns were pregnant. The Simbas were unbelievable bastards. But we did it, and made a big difference in many lives. I found that rewarding.”

Over the next year Colonel Hoare and his men liberated the remainder of the Congo from the Simbas and restored law and order. Tshombe, his job done, fell from grace; soon, he was kidnapped and he died in prison in Algeria in 1969. General Joseph Mobutu, the Congo’s strong-man supremo, looted the country to ruin over the next three decades.

Mike Hoare recent activities.

Mike Hoare recent activities.

In 1981, Mike Hoare and a group of mercenaries posing as a beer-drinking group, flew to the Seychelles to topple the socialist president. It all went wrong at the airport, they flew back to South Africa in an Air India Boeing 707, and were immediately arrested. The newspapers called it a hijack. Hoare received a 10-year jail sentence, but was granted an amnesty in 1985 after serving 33 months. After a few unsettled years, he and his wife Phyllis went to live in his beloved France near Toulouse, looking after a chateau for a British lord. Mike soon developed a passion for the Cathars, a Christian sect who lived in those parts during the Middle Ages. He spent the next 14 years researching the beliefs of the Cathars and visiting the historical sites. In 2005 he went to live near Annecy, also in France, and when his wife of some 48 years died in 2009, he moved back to South Africa to live with his sons from his first marriage. He completed his work on the Cathars and self-published a book titled: The Last Days of the Cathars.

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers

Soldier of Fortune Magazine The Journal of Professional Adventurers